pre-course activity - EGAPhilosophy

advertisement

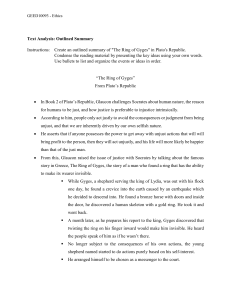

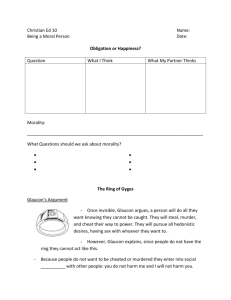

A-level Philosophy Pre-course activity Summer 2014 Introduction Before the first lesson of the term (on 3rd September 2014) you will need to complete the following task. It requires no previous knowledge of Philosophy – it requires you research a classic thought experiment, and present your findings in an essay. The purpose of the task is to give your teachers a feel for how you organize your thoughts, and arguments, in an essay. So please do put time, care and effort into expressing yourself clearly, and in depth. The task Given a written answer to the following questions: What is the story of the Ring of Gyges meant to show? Do you find the argument convincing? Explain your answer. Your answer should be in continuous prose (i.e. using full sentences, paragraphs and punctuation). It should be at least 300 words long. Try and write it all in your own words – if you do need to include a direct quotation from a book/the internet, please make it clear [write in brackets – “this is a quotation from The Republic by Plato” for example]. Resources Links to a few internet sites which explain the myth of Gyges are given below, and on the EGA Wikispaces page. The original description of the thought experiment (as it was given by Plato) is given on the next page. Feel free to use any internet resources – but you are strongly recommended to start with the ones given. A lot has been written about this bit of text, and most of it is aimed at university students and academics. The story of the Ring of Gyges, as described by Glaucon in “The Republic” by Plato. Glaucon is arguing with Socrates about the nature of morality. Gyges was a shepherd in the service of the king of Lydia; there was a great storm, and an earthquake made an opening in the earth at the place where he was feeding his flock. Amazed at the sight, he descended into the opening, where, among other marvels, he beheld a hollow horse made of brass, with doors. He stooped and, looking in, saw a dead body of stature, who appeared to be more than a mere human, wearing nothing but a gold ring; this he took from the finger of the dead man and climbed back out. Now the shepherds met together, according to custom, that they might send their monthly report about the flocks to the king; into their assembly he came, with the ring on his finger. As he was sitting among them he chanced to turn the collet of the ring inside his hand, and instantly he became invisible to the rest of the company - they began to speak of him as if he were no longer present. He was astonished at this, and again touching the ring he turned the collet outwards and reappeared; he made several trials of the ring, and always with the same result-when he turned the collet inwards he became invisible, when outwards he reappeared. Whereupon he contrived to be chosen as one of the messengers who were sent to the court of the king; as soon as he arrived he seduced the queen, and with her help conspired against the king and slew him. He then took control of the kingdom. Suppose now that there were two such magic rings, and a virtuous person put on one of them and an unvirtuous person the other; no man can be imagined to be of such an iron nature that he would remain virtuous. No man would keep his hands off what was not his own when he could safely take what he liked out of the market, or go into houses and sleep with any one at his pleasure, or kill or release from prison whom he would, and in all respects be like a God among men. Then the actions of the virtuous would be the same as the actions of the unvirtuous; they would both come at last to the same point. And this we may truly affirm to be a great proof that a man is virtuous, not willingly or because he thinks that virtue is any good to him individually, but of necessity - wherever any one thinks that he can safely be unvirtuous, there he will be unvirtuous. This is because all men believe in their hearts that injustice is far more profitable to the individual than justice, and anyone who argues as I have been, will say that they are right. If you could imagine any one obtaining this power of becoming invisible, and never doing any wrong or touching what was another's, he would be thought by the lookers-on to be a most wretched idiot, although they would praise him publicly, and keep up appearances with one another from a fear that they too might suffer injustice. Hints about writing it There are two questions to answer – make you sure you answer them both. Make a written plan of what you are going to say before you start. For example …. Intro to Plato – who he was Context to the story in the The Republic What the myth says What it is meant to show A few examples of what it means Why I disagree with it – counter-arguments Conclusion Make it clear when you are describing the facts – who Plato was, who is describing the myth in the Republic, what Glaucon says - and when you are describing what you think of it. It is best to put any of your thoughts (about whether the claim Glaucon makes is convincing) in a separate paragraph. Imagine you are explaining the story, and what is trying to show to a group of interested, intelligent adults, who know nothing about Plato. This should give you an idea of how much depth to go into. Double-check that what you have written makes sense. It is easy to miss out words, and get tangled up in long sentences. Make it concise and clear.