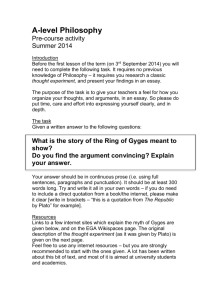

A Summary of Glaucon`s Argument

advertisement

11Example As we open Book II of Plato’s Republic we are introduced to Glaucon, a philosopher concerned with the value of justice. He has gotten stuck trying to decide if there’s any value in simply being a just person; when all he comes across are the consequences of being just, he finds no reason to prevent a person from being unjust if they can get away with it. Glaucon thus challenges Socrates to prove the goodness of being just after he forcibly argues his two main points against it. Glaucon’s first point supports Thrasymachus’ argument from Book I: a belief that everything good and of value in the world can be presented through taxonomy of value and placed into one of three different categories. The first of its three categories is meant for the things that are “a kind of good we like for its own sake (Plato 33)”. The second category is for what’s good as a result of their consequences- such as exercise for fitness and sex for pleasure and children. The highest category is for things that are both good in themselves and because of their consequences. When Socrates was questioned as to where justice belonged, his answer fell into this latter category, “among the finest goods (34)”. Glaucon argued that nothing’s good if it fails to sort into one of these three groups. The weakness in his argument, however, is that everything- from going to work to having sex, is still good for its own sake, thus destabilizing the second category and his second point. However, Plato includes the entire case verbatim in his book of virtue-based ethics as a means of having a more intelligent and effective argument for Socrates to challenge in the future. Continuing the challenge and reinforcing his second point, Glaucon tries to eliminate any remaining shreds of the idea that justice may possess any intrinsic value. He now argues that justice is only valuable because of its good consequences and not because of what it’s inherently worth (Plato 32). Glaucon then places justice in the second category of his taxonomy where he begins his first step in arguing that justice has no inherent goodness due to the basis of its origins. He believes justice was created as a result of the laws and covenants that were formed by those who suffered injustice but were too weak to inflict it themselves- thus creating a compromise that serves as the most profitable alternative for the majority. Glaucon proceeds to argue a second point, where “…all who practice it [justice] do so unwillingly (35)”. He tells a story where a just man finds a ring that can make him invisible. Having no consequences for doing wrong he delves into his inhibitions and is as immoral as he pleases. This leads up to Glaucon’s third point, where he argues, “…the life of an unjust person is, they say, much better than that of a just one (34).” In his example, the just man undergoes a torturous lifetime of humility and poverty, whereas the unjust man assimilates enough power and luxury that it enables him to purchase the title of a just man. Glaucon’s premises offer good logic; and though they lack real merit, they do an effective job of presenting a strengthened argument in Plato’s Republic. With the end of Book II the plot has thickened, and Socrates will have to answer to a stronger challenge.