Post Anesthesia Respiratory Complications in

advertisement

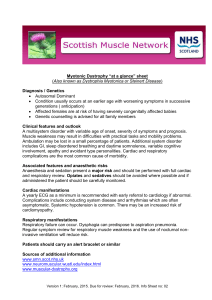

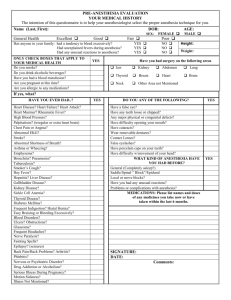

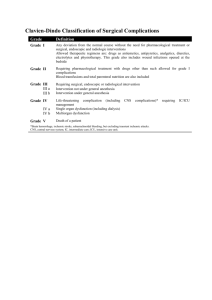

Running head: POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS Post Anesthesia Respiratory Complications in Children Exposed to Second Hand Smoke Aaron Duebner Texas A&M University Corpus Christi Research Design in Nursing NURS 5314 Dr. Sara Baldwin November 26, 2013 1 POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 2 Post Anesthesia Respiratory Complications in Children Exposed to Second Hand Smoke Each year approximately 450,000 children in the United States are admitted to inpatient settings for surgery, of these children approximately 115,000 are under three years old (Tzong KY ; Han S ; Roh A ; Ing C, 2012). Many of these cases are elective in nature with the majority being urological, orthopedic or gastrointestinal (Tzong et al., 2012). While anesthesia in otherwise healthy pediatric patients is often considered low risk,” respiratory adverse events are the most common perioperative critical event” (So Yeon et al., 2013, p. 137 ) associated with anesthesia. Some aspects related to respiratory complications in the surgical setting such as procedural techniques and sedation methods can vary widely among surgeons and anesthesiologists, and can be difficult to quantify. Other respiratory risks such as pre-procedural exposure to second hand smoke can more easily be measured. The purpose of this problem investigation is to evaluate the evidence in relation to pediatric exposure to second hand or passive smoke and post anesthesia respiratory complications. The author’s aim is to identify perianesthesia risk associated with exposing children to passive smoke so that a knowledge base can be developed to provide an evidenced based intervention strategy to pediatric patients and their families prior to anesthesia services. Identification of Problem and Importance to Nursing Practice Passive or second hand smoke is defined as” the caseous by- product of burning tobacco products...it has been further defined as 15% mainstream smoke and 85% sidestream smoke from a smoldering cigarette. It is estimated that there are upwards of 4000 chemical compounds in environmental tobacco smoke (ETS)” (Thikkurissy, S., Crawford, B., Groner, J., Stewart, R., & Smiley, M, 2012, p. 143). Lyons (2012) states the World Health Organization in 2005 estimated that approximately 57.2% of children worldwide were exposed to passive smoke at home. What POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 3 is known about passive smoking and its effects on children undergoing anesthesia is that evidence shows there to be an” increased incidence of perioperative coughing, laryngospasm, hypoxemia, bronchospasm, and overall respiratory complications by up to 60% “(O’Rourke, J.M., Kalish, L.A., McDaniel, S., & Lyons, B., 2006, p. 566). One reason this is of importance in nursing is because it is a modifiable risk factor. This means that nurses have the opportunity during their assessments to identify at risk individuals and their families and provide interventions such as patient education regarding increased anesthesia risk and referral to smoking cessations programs. Another area of importance includes the need for respiratory interventions involving the nurse such as breathing treatments, rescue measures (suctioning/bagging), and oxygen support. Finally, the need for bedside interventions mean increased cost related to elongated perianesthesia time; this includes turnover time, anesthesia billing, and facility costs. According to O’Rourke et al. (2006), one way to mitigate these complications is to arrange for Pulmonary Function Testing. PFT can help determine the severity of lung dysfunction in children prior to anesthesia procedures. Furthermore, the authors conclude that the use of this simple, noninvasive and inexpensive test can help to identify at risk patients and provide the opportunity for additional testing or interventions (O’Rourke et al., 2006). Conceptual Model/Theory Children are primarily exposed to passive smoke in the home which makes smoking cessation of a child’s caregiver a priority. According to (Winickoff et al., 2008), “ the 2006 Surgeon General's Report on the health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke emphasizes that SHS is a major cause of disease, with no safe level of exposure”. Caregiver smoking cessation prior to anesthesia can be initialized in the clinical setting during pre- POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 4 procedure consultations or during routine physical exams. ” Parental smokers often see their child's healthcare clinician more frequently than their own, with an average of over four visits per year, and 11 pediatric well-child visits in the first two years of a child's life. Therefore, child healthcare offices are in a key position to influence, in a repeated and consistent manner, parents who are willing to address their smoking” (Winickoff et al., 2008, p. 365). One middle-range nursing theory that can be used to accommodate this intervention is Pender’s Health Promotion Model. This theory has two individual assessment components. The first part directs the nurse to assess the client for health promoting behaviors including: self – efficacy, perceived barriers, perceived benefits, and interpersonal and situational influences. The second portion has the nurse assess client characteristics that may provide insight into health behaviors such as: prior behavior, demographic characteristics, and perceived health status. Through the use of information based on this assessment the nurse can tailor a plan to help the client achieve improved health (Peterson & Bredlow, 2013, Chapter 14). In this case the improved health would benefit both the parent and the child, and significantly reduce the risk for respiratory complications for the child undergoing anesthesia. Practice Problem As mentioned earlier, nearly a half a million children in the United States will undergo surgery each year, add to that the number of children undergoing anesthesia for day surgery and diagnostic procedures, one then sees that the scope of pediatric anesthesia is vast. Many times a child will present in the surgical setting with respiratory symptoms attributable to second hand smoke exposure such as middle ear disease, low birth weight, lower respiratory illness, asthma, increased mucous production or cough (Best, D., Committee on Environmental Health, Committee on Native American Child Health and Committee on Adolescence, 2009). POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 5 These children are then anesthetized utilizing varying techniques. According to the literature most children receive inhalation gas anesthesia (sevoflurane, nitrous oxide) followed by tracheal intubation or the use of an LMA (Lyons, 2011)(Dragonowsi et al., 2003). The following question attempts to determine the respiratory risk in the pediatric population exposed to SHS after anesthesia in the recovery phase. PICO Question The PICO question for this statement of a problem paper is: Are children undergoing surgery, which have been exposed to second hand smoke at increased risk for respiratory complications during the post anesthesia recovery phase? Respiratory complications can be measured both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitative measures include pulse oximetry values, carboxyhemoglobin values, PFT results, oxygen delivery, and recovery time. Qualitative measures include evaluation of mucous production, ease of emergence, and amount of coughing and presence/absence of wheezing (Dragonowsi et al., 2003). These signs and symptoms of respiratory complications or lack thereof can be assessed by the nurse at the bedside, in the operating room or in the recovery area. Operational Variables The dependent variable in this investigation is respiratory complications. Respiratory complications in this situation are hypothesized to increase or decrease following the manipulation of the independent variable which is second hand smoke. The PICO question presented attempts to answer whether children exposed to second hand smoke (independent variable) have an increased risk of respiratory complications (dependent variable) post anesthesia. The causal relationship between respiratory complications following pediatric exposure to second hand smoke is the focus of this research. By manipulating the exposure of POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 6 second hand smoke, preferably eliminating in through caregiver education, the expected outcome is to see a decrease in the amount of respiratory complications following anesthesia in children. Moderator variables include in utero versus postnatal exposure, amount of exposure (number of cigarettes smoked by caregivers for X amount of time), airway management, induction agent, use of reversal agent, and presence or absence of secondary health issues such as the presence of a cold, nasal congestion, presence of sputum, or snoring history, (So Yeon, et al., 2013) (O’Rourke et al., 2006). According to O’Rourke (2006), “Children who have a had a history of ETS present a greater risk of anesthesia, but this risk needs to be evaluated in the context of other factors that could contribute to respiratory complications “(O’Rourke, J.M., Kalish, L.A., McDaniel, S., & Lyons, B., 2006, p. 565). Summary The literature shows a preponderance of evidence regarding the increase in respiratory complications following anesthesia in pediatric patients exposed to second hand smoke (passive smoking, environmental exposure to smoke). The literature documents that in healthy children, studies show an “increase in the frequency of respiratory symptoms during the recovery room stay in the smoke exposed population (56%) compared with the non-exposed (31%)”. However the total RR time was similar (Dragonowsi et al., 2003, p. 309). According to O’Rourke (2006), perioperative complications such as “laryngospasm, bronchospasm, wheeze, coughing, stridor, increased mucous production, and oxygen desaturations occur more frequently in ETS exposed children. There is also a dose-response correlation between the complications and the degree of exposure” (O’Rourke et al., p. 565). The mechanism behind the increase in respiratory symptoms is systemic inflammation from inflammatory cytokines released by basal cells, activated by the smoke damaged epithelium POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 7 (Lyons, 2011). Studies also suggest that smoking is known to “induce drug metabolizing enzymes, especially in the liver” (Resli et al., 2004, p. 247). This might affect emergence as well. Finally, the literature supports the need for nurses and physicians to initiate discussion regarding caregiver use of tobacco and the exposure of children in their care to second hand smoke. Early attempts to talk with caregivers about smoking cessation could provide opportunities for education and potentially alleviate health complications both in the clinical setting and in the surgical setting. Several office based intervention programs are documented in the literature. One evidence-based interventions listed is the 5A’s for child health care clinicians. This involves asking about tobacco use at every visit, advise all tobacco users to quit, assess readiness to quit, assist in quitting, and arrange follow up (Winickoff, 2005, p. 755). While time management is always a concern, especially in a pediatric office, it is important to utilize available staff such as nurses to facilitate this intervention and also provide information for telephone quit lines that can provide more extensive counseling (Winickoff, 2005). A study by Liles (2009), showed that” blending smoking cessation counseling with SHS reduction counseling can increase the quite attempts made by low-income mothers with young children Liles, Hovell, Matt, Zakarian, & Jones, 2009, p. 1402). Through the use of pre-procedural efforts to eliminate children’s exposure to second hand smoke, and the identification of children exposed prior to surgery, nurses and clinicians can better care for pediatric patients in the surgical setting. While the evidence shows children exposed to second hand smoke are at increased risk for respiratory complications in the post anesthesia recovery phase, it also shows that an informed staff can anticipate and quickly respond to potential complications decreasing the likelihood of an adverse event. POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 8 References Best, D., Committee on Environmental Health, Committee on Native American Child Health and Committee on Adolescence. (2009, October, 19). Secondhand and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure. PEDIATRICS, 124(), 1017-1044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.20092120 Dragonowsi, R. A., Lee, D., Reynolds, P. I., Malviya, S., Harmon, C. M., Geiger, J., ... Coran, A. G. (2003). Increased respiratory symptoms following surgery in children esposed to environmental tobacco smoke. Paediatric Anesthesia, 13(4), 304-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01100 Liles, S., Hovell, M. F., Matt, G. E., Zakarian, J. M., & Jones, J. A. (2009, December 29). Parent quit attempts after counseling to reduce children’s secondhand smoke exposure and promote cessation: Main and moderating relationships. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 11(12), 1395-1406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp149 Lyons, A. (2011). Pediatric respiratory complications after general anesthesia with exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in the home: a case report. AANA Journal, 79(1), 20-23. Retrieved from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.manowar.tamucc.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=0ed2ed0d5e47-4912-bce8-32a2671b1481%40sessionmgr4001&vid=4&hid=4113 O’Rourke, J.M., Kalish, L.A., McDaniel, S., & Lyons, B. (2006). The effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke on pulmonary function in children undergoing anesthesia for minor surgery. Pediatric Anesthesia, 16(5), 560-567. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01821 POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS 9 Peterson, S. J., & Bredlow, T. S. (2013). Chapter 14: Health Promotion. In Middle range theories: Application to nursing research (3rd ed., pp. 225-234). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. Resli, R., Apilliogullari, S., Reisli, I., Tuncer, S., Erol, A., & Okesli, S. (2004, March). The effect of environmental tobacco smoke on the dose requirements of rocuronium in children. Pediatric Anesthesia, 14(3), 247-250. Retrieved from So Yeon, K.,Jeong Min, K., Jae Hoon, L., Young Ran, K., Seung Ho,J., & Bon-Nyeo, K. (2013). Perioperative respiratory adverse events in children with active upper respiratory tract infection who received general anesthesia through an orotracheal tube and inhalation agents. Korean Journal Of Anesthesiology, 65(2), 136-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2013.65.2.136 Thikkurissy ,S., Crawford, B., Groner, J., Stewart, R., & Smiley, M. (2012). Effect of passive smoke exposure on general anesthesia for pediatric dental patients. Anesthesia Progress, 59(4), 143-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.2344/0003-3006-59.4.143 Tzong KY ; Han S ; Roh A ; Ing C. (2012, October). Epidemiology of pediatric surgical admissions in US children: data from the HCUP kids inpatient data base. Journal Of Neurosurgical Anesthesiology, 24(4), 391-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ANA.0b013e31826a0345 Winickoff, J. (2005). State-of-the-art interventions for office-based parental tobacco control. Pediatrics, 115(3), 750-760. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1055 Winickoff, J. P., Park, E. R., Hipple, B. J., Berkowitz, A., Vieria, C., Friebely, J., ... Rigotti, N. A. (2008, August, 1). Clinical effort against second hand smoke exposure (cease): POST ANESTHESIA RESPIRATORY COMPLICATIONS development of framework and intervention. PEDIATRICS, 122(2), e363-e375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0478 10