SC - MA Thesis - Final Draft - MacSphere

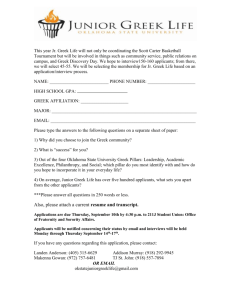

advertisement