here - Jay Kennedy, History and Philosophy of Science

advertisement

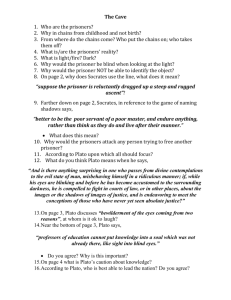

The Rise and Fall of Platonic Love Some Lively Background to the Press Release XXXX Words plus some pics The Birth of Platonic Love in Plato The idea of Platonic love came from the story of a famous seduction. A notorious youth once invited Plato’s teacher to come to his mansion for dinner.1 The youth was fabulously wealthy and regarded as a great beauty. He pressed the teacher to talk philosophy late into the night and then insisted he stay over. Figure: Plato’s teacher Socrates portrayed as anti-sex. He drags the young Alcibiades away from a life of pleasure (Jean-Baptiste Regnault, 1791). The young man knew that, like many Greeks, the teacher had a taste for teenage boys and woke him in the dark. The youth offered himself to the teacher, whispering that he was willing to do anything to become his student. The teacher mocked him for trying to exchange the beauty of his body for eternal wisdom. 1 The young man is Alcibiades (al-si-BUY-a-dees). The teacher was Socrates. Nothing happened. They slept on the same couch together all night long. The young man said “it was as if I slept with my father or brother.” This intimate episode is one of the great scenes in world literature. It shows Plato’s teacher using super-human willpower to resist sexual temptation. Figure: Plato’s story about how his teacher withstood the seductive charms of the young Alcibiades became an enduring image of Plato’s opposition to sex (FrançoisAndré Vincent, 1777) It was also a pivotal moment politically. The charismatic young man turned from sex-symbol and “it-boy” into the great villain of Greek history. As a young general, his betrayal of Athens led to the collapse of her empire. Plato suggests that his teacher had damaged the young man. Sexual rejection turned him toward evil. The Greeks later remembered this youth as if he were a weird combination of Marilyn Monroe and Hitler. Many believe that this story shows that Plato’s ideal philosopher would never consummate his love -- no matter what the costs. Some passages in Plato do celebrate erotic passion. He tells funny stories about successful seductions and treats sex as a step toward true and lasting love. For him, heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual orientations were all equally natural. Plato was also an early feminist. He allowed female students into his school as long as they dressed like men. Before this new discovery of Plato’s symbolic code, Plato’s views on sex seemed ambiguous. Although most believed he was an advocate of Platonic Love, his books could, like the Bible, be read as pro-sex or anti-sex. Modern Platonic Love Spreads from Florence to London Plato’s books were lost in the Dark Ages. About five hundred hears ago, the wealthy Medici bankers paid to translate copies of Plato’s works from the East and helped spread them through Europe. This led to a rediscovery of paganism and a frank enthusiasm for the human body and erotic passion. The great icon of this shift away from Christian hostility to sex is Botticelli’s Venus on the Half Shell. Botticelli was the Medici’s house painter and turned from pious paintings of the Virgin Mary to the naked Greek goddess of love. Figure: The Medici dynasty spread Platonism and paganism. Botticelli’s Venus on the Half Shell was commissioned for a Medici wedding. It has been interpreted as an illustration of Plato’s ideas (c. 1486). This new celebration of nudity and sexuality was clothed in respectability by talk of ‘Platonic love’ (in Latin, amor Platonicus). The new religion of love was to be spiritual and chaste. Unlike Christianity, however, bodily love was not a sin but a natural step toward higher, spiritual love. Unlike Christianity, which celebrated the love between God and man, Platonic love celebrated the love between two, equal souls. The homoerotic elements in Plato were dropped, and they emphasized the love between a man and a woman. The new fashion in love spread quickly from the Medici’s court in Florence to the French court. Platonic love revolutionized art and literature, but also the way men and women pursued each other. Since only love between souls mattered, convention and social form could be cast aside. Paradoxically, the idea that physical love was unimportant quickly made it permissible. Platonic love became a license for free love. Postponing sex was an important step toward the equality of women. The Queen of England even commissioned plays to spread the idea. At a time when women were treated as slaves or baby-machines, ‘Platonic love’ meant longer courtships and delaying the dangers of childbirth. Figure: Queen Henrietta Maria was the daughter of Catherine d’Medici and brought the new cult of Platonic love to the English court (Van Dyck, c. 1632). Queen Henrietta Maria of England brought the new style of love-making from France to England. She lived to see her husband King Charles I beheaded at the beginning of the Civil War. The decadence of the royal court inflamed the Puritans and pushed them toward open rebellion. Figure. The bleeding head of King Charles I is held aloft. The Catholic religion and Platonistic philosophy of his queen pushed the Puritans toward open revolt. The young Queen was the daughter of the French king and his wife, Catherine de Medici. She imported French permissiveness and the Italian fashion for Platonic love into her court in London. A private letter written by an aristocrat at the time, tells of the change: The Court affords little News at present, but that there is a Love call'd Platonick Love, which much sways there of late; it is a Love abstracted from all corporeal gross Impressions and sensual Appetite, but consists in Contemplations and Ideas of the Mind, not in any carnal Fruition. This Love sets the Wits of the Town on work; and they say there will be a Play shortly of it, whereof Her Majesty and her Maids of Honour will be part.2 In the generation after Shakespeare, the Queen pushed for plays that spread the idea of Platonic love. When no woman could appear on stage, she and the young women in court acted in plays in the palace celebrating the new love religion. Letter of James Howell, June 3, 1634 in Epistolae Ho-Elianae (London, 1890), I, 317-18. I have amended “Masque” to “Play”. 2 Figure: Queen Henrietta Maria sponsored a theatre company that spread new ideas about Platonic love. The title page John Ford’s play about incest and debauchery, “Tis Pity She’s a Whore” (1633) The Queen also commissioned new plays for the public theatre. Already in 1629, a play by Ben Jonson redefined love: Love is a spiritual coupling of two souls. The end of love, is to have two made one in will, and in affection, that the minds be first joined, not the bodies.3 Another playwright, William Davenant (Shakespeare’s godson) wrote a play entitled The Platonick Lovers. One of his female characters explained that Platonic love meant a new freedom for women: I have amended the word “inoculated” to “joined” which is its obsolete meaning. Jonson, The New Inn. 3 You men, when you enjoy what you desire, cool in affections, and being married we lose our price and value. While we keep our freedom, you pour forth your service to us, and study new ways of devotion.4 As one historian put it, the playwrights found their “romantic theory of Platonic love … in Henrietta Maria's Platonic cult.”5 The Puritans rose up to attack the theatre. One wrote an 1100 page book proving that plays were the devil’s work and all actresses were “notorious whores.”6 This was interpreted as an attack on Queen Henrietta Maria herself. The author was convicted of treasonous libel, fined, sentenced to life imprisonment – and had both his ears cut off. The grueling years of the Civil War ended the fashion for Platonic love in the royal court. Its brief reign gave birth to the idea that Plato was anti-sex, and this became a permanent part of our culture. Discovery of Plato’s True Views on Sex The new book cracks Plato’s symbolic code and reveals he was no advocate of Platonic love, as the following three examples explain. About one-third of the new book is devoted to Plato’s treatise on sex and love. The musical code shows that Plato endorses sex when it is part of a true and abiding love. If Plato approves of an idea, he puts it at the position of harmonious note. Another famous scene provides an example. Plato pictures two young lovers lying together intimately in each other’s arms. The god of blacksmiths, Hephaestus, surprises them and offers to weld them together. This will unite the lovers physically for the rest of their lives. Plato inserts this luminous story at The Careless Shepherdess, p. 15. Ford 226 6 William Prynne, Histriomastix (1632). 4 5 one of the most harmonious notes. Figure. Symbolic passages are located at harmonious and dissonant notes. A major argument of the book is that Plato rejected both promiscuity and abstinence. Morality meant a middle path between a life of pleasure and asceticism. Plato’s symbolism repeatedly associates the idea of a mathematical average or mean with a middle path between pleasure and pain. Plato’s student Aristotle also advocated a middle path between pleasure and pain, and thought of sex as a natural part of the moral life.7 The new book argues that there is a close correspondence between Plato’s encoded doctrine and Aristotle’s view. Thus the symbols in Plato’s book on love and sex reveal is hidden philosophy: not the abstinence of Platonic Love but sex as a natural part of true love. 7 Nichomachean Ethics, Bk. II, etc.