A Guide to Action for Initiative Implementation

advertisement

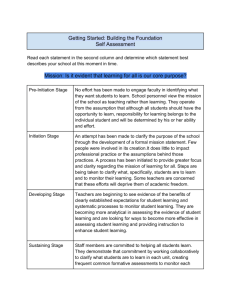

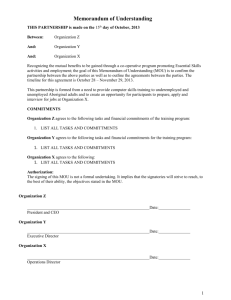

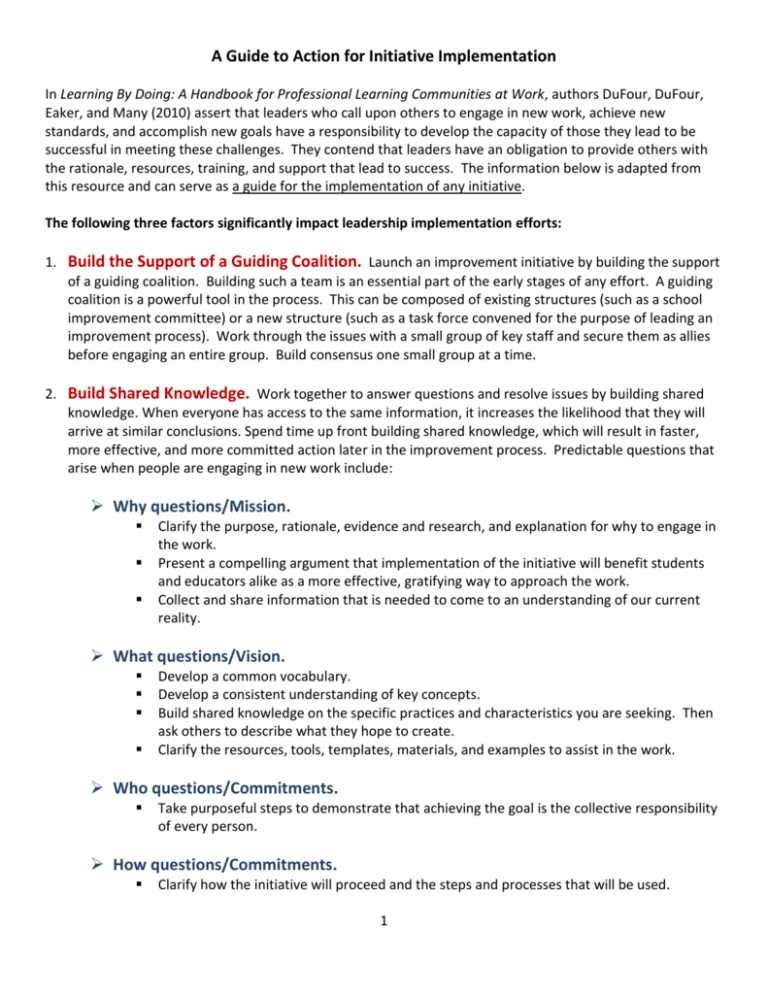

A Guide to Action for Initiative Implementation In Learning By Doing: A Handbook for Professional Learning Communities at Work, authors DuFour, DuFour, Eaker, and Many (2010) assert that leaders who call upon others to engage in new work, achieve new standards, and accomplish new goals have a responsibility to develop the capacity of those they lead to be successful in meeting these challenges. They contend that leaders have an obligation to provide others with the rationale, resources, training, and support that lead to success. The information below is adapted from this resource and can serve as a guide for the implementation of any initiative. The following three factors significantly impact leadership implementation efforts: 1. Build the Support of a Guiding Coalition. Launch an improvement initiative by building the support of a guiding coalition. Building such a team is an essential part of the early stages of any effort. A guiding coalition is a powerful tool in the process. This can be composed of existing structures (such as a school improvement committee) or a new structure (such as a task force convened for the purpose of leading an improvement process). Work through the issues with a small group of key staff and secure them as allies before engaging an entire group. Build consensus one small group at a time. 2. Build Shared Knowledge. Work together to answer questions and resolve issues by building shared knowledge. When everyone has access to the same information, it increases the likelihood that they will arrive at similar conclusions. Spend time up front building shared knowledge, which will result in faster, more effective, and more committed action later in the improvement process. Predictable questions that arise when people are engaging in new work include: Why questions/Mission. Clarify the purpose, rationale, evidence and research, and explanation for why to engage in the work. Present a compelling argument that implementation of the initiative will benefit students and educators alike as a more effective, gratifying way to approach the work. Collect and share information that is needed to come to an understanding of our current reality. What questions/Vision. Develop a common vocabulary. Develop a consistent understanding of key concepts. Build shared knowledge on the specific practices and characteristics you are seeking. Then ask others to describe what they hope to create. Clarify the resources, tools, templates, materials, and examples to assist in the work. Who questions/Commitments. Take purposeful steps to demonstrate that achieving the goal is the collective responsibility of every person. How questions/Commitments. Clarify how the initiative will proceed and the steps and processes that will be used. 1 Initiate structures and systems to foster what you’re trying to create. When something is truly a priority, people do not hope it happens; they develop and implement systematic plans to ensure it happens. Determine the commitments necessary from each person involved in making the initiative a success. Leaders can model a willingness to make commitments by identifying the specific things they will do to support the effort. Quality questions/Goals. Determine the criteria that will be used to judge the quality of the work. Identify the benchmarks of success at different time frames (six months, a year, three years, for example). Create processes to monitor critical conditions and important goals. What gets monitored gets done. A critical step in moving from rhetoric to reality is to establish the indicators of progress to be monitored, the process for monitoring them, and the means of sharing results throughout the organization. Key components of why, what, who, how, and how will we know if this makes a difference are summarized below: Mission Vision • The purpose Commitments Goals • The compelling future • The accompanying actions • The targets and timelines • Answers what • Answers who and how • Answers how will we know if this makes a difference • Answers why • Clarifies priorities and sharpens focus • Gives direction • Guides the work and outlines how every person contributes • Establishes priorities Additional questions to address in building shared understanding involve the following: When questions. Determine the time for when the work will be done. Clarify the task completion dates and the timeline. Guiding questions. Be clear about the questions we are attempting to answer and the questions that will help us stay focused on the right work. Assurance questions. Offer suggestions and cautions that increase the likelihood of success. Specify where to receive support and assistance. 2 3. Take Specific Leadership Actions That Convey Commitment to the Initiative. Implementing the specific leadership actions below convey commitment to the initiative: Practice “reciprocal accountability” – For every increment of performance that is demanded, an equal responsibility exists to provide the capacity to meet that expectation. Likewise, for every investment made in one’s skill and knowledge, a reciprocal responsibility exists to demonstrate some new increment in performance (Elmore, 2006). Reallocate resources to support the proclaimed priorities. Money and time talk. Pose the right questions. The questions posed and the effort and energy spent in the pursuit of answers communicate priorities and set direction. Model what is valued. Demonstrate commitment by focusing on the priority and keeping the issue constantly before others. Leaders must model the approach they want others to embrace. Celebrate progress toward goal attainment. Frequent public acknowledgments for a job well done and a wide distribution of small symbolic gestures of appreciation are powerful tools for communicating priorities and values (see handout for incorporating celebrations) . Confront violations of commitments. An unwillingness to confront these violations puts the initiative at risk. Reject the fixed mindset that attributes accomplishments to innate ability or dispositions that cannot be enhanced. Embrace the growth mindset, which is the belief that students can cultivate their ability and talent through their own effort and the support of their educators (Dweck, 2006). Move quickly to action. Identify existing practices that should be eliminated. Translate the vision into a teachable point of view (TPOV), which is a succinct explanation of the effort that can be illustrated through stories that engage others emotionally and intellectually (Tichy, 1997). Communicate that the process is nonlinear, and discuss the concepts of experiencing disequilibrium and tolerating ambiguity as normal aspects of the change process. It is the dialogue about and the struggle with the initiative at the school and district level that result in the deepest learning and greatest commitment. Adapted from: DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., & Many, T. (2010). Learning by doing: A handbook for professional learning communities at work (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press. See also: www.allthingsplc.info and go.solution-tree.com/PLCbooks 3 4