KISON Trinity Isabel - Courts Administration Authority

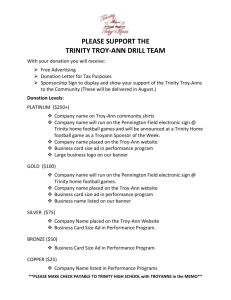

advertisement