how miss cow fell victim to mr. rabbit - Global Studies

advertisement

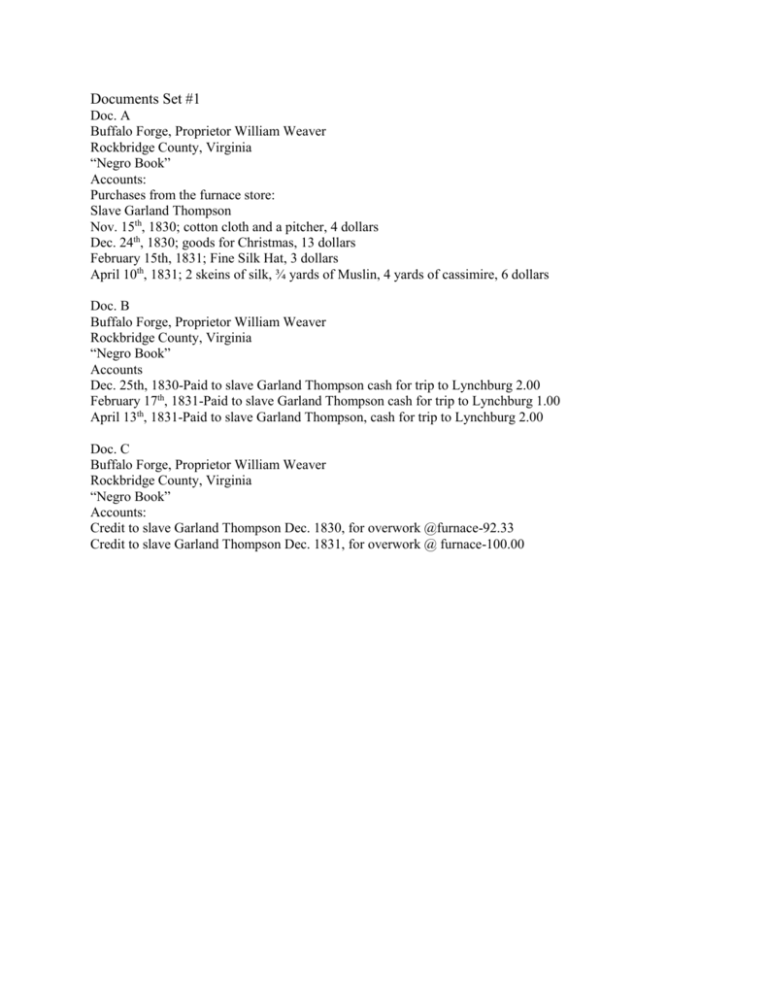

Documents Set #1 Doc. A Buffalo Forge, Proprietor William Weaver Rockbridge County, Virginia “Negro Book” Accounts: Purchases from the furnace store: Slave Garland Thompson Nov. 15th, 1830; cotton cloth and a pitcher, 4 dollars Dec. 24th, 1830; goods for Christmas, 13 dollars February 15th, 1831; Fine Silk Hat, 3 dollars April 10th, 1831; 2 skeins of silk, ¾ yards of Muslin, 4 yards of cassimire, 6 dollars Doc. B Buffalo Forge, Proprietor William Weaver Rockbridge County, Virginia “Negro Book” Accounts Dec. 25th, 1830-Paid to slave Garland Thompson cash for trip to Lynchburg 2.00 February 17th, 1831-Paid to slave Garland Thompson cash for trip to Lynchburg 1.00 April 13th, 1831-Paid to slave Garland Thompson, cash for trip to Lynchburg 2.00 Doc. C Buffalo Forge, Proprietor William Weaver Rockbridge County, Virginia “Negro Book” Accounts: Credit to slave Garland Thompson Dec. 1830, for overwork @furnace-92.33 Credit to slave Garland Thompson Dec. 1831, for overwork @ furnace-100.00 Doc. D NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS, AN AMERICAN SLAVE. Author: Frederick Douglas, 1845 “I had resided but a short time in Baltimore before I observed a marked difference, in the treatment of slaves, from that which I had witnessed in the country. A city slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on the plantation. He is much better fed and clothed, and enjoys privileges altogether unknown to the slave on the plantation. There is a vestige of decency, a sense of shame, that does much to curb and check those outbreaks of atrocious cruelty so commonly enacted upon the plantation. He is a desperate slaveholder, who will shock the humanity of his non-slaveholding neighbors with the cries of his lacerated slave. Few are willing to incur the odium attaching to the reputation of being a cruel master; and above all things, they would not be known as not giving a slave enough to eat. Every city slaveholder is anxious to have it known of him, that he feeds his slaves well; and it is due to them to say, that most of them do give their slaves enough to eat” Doc. E Frederick Douglas, Slave Narratives “The slave is a human being, divested of all rights-reduced to the level of a brute-a mere chattel in the eye of the law-placed beyond the circle of human brotherhood-cut off from his kind. His name, which the recording angel may have enrolled in heaven among the blest, is impiously inserted in a master’s ledger with horses, sheep, and swine”. Doc. F Connecticut Puritan Solon Robinson, 1849 “A greater punishment could not be devised or inflicted upon the southern slave at this day than to give him that liberty which God in his wisdom and mercy deprived him of…Free them from control, and how soon does poverty and wretchedness overtake them… I doubt whether one single instance can be found among the slaves of the south where one has injured himself at long and excessive labor. Instead of a cruel and avaricious master being able to extort more than a very reasonable amount of labor from him, his efforts will surely produce the contrary effect” Doc. G Charles Pinckney's Speech to Congress, 1820 From Annals of Congress, the Sixteenth Congress First Session, V. 2 (1820). Washington: Governmental Printing Office, 1855. 1323-1328. Every slave has a comfortable house, is well fed, clothed, and taken care of; he has his family about him, and in sickness has the same medical aid as his master, and has a sure and comfortable retreat in his old age, to protect him against its infirmities and weakness. During the whole of his life he is free from care, that canker of the human heart, which destroys at least one half of the thinking part of mankind, and from which a favored few, very few, if indeed any, can be said to be free...The great body of slaves are happier in their present situation than they could be in any other, and the man or men who would attempt to give them freedom, would be their greatest enemies… In a pecuniary view of this subject, therefore, it must ever be the policy of the Eastern and Northern States to continue connected with us. But, sir, there is an infinitely greater call upon them, and this is the call of justice, of affection and humanity. Reposing at a great distance, in safety, in the full enjoyment of all their Federal and State rights, unattacked in either, or in their individual rights, can they, with indifference, or ought they to risk, in the remotest degree, the consequences which this measure may produce. These may be the division of this Union and a civil war. Document Set #2: A) The Impending Crisis of the South, 1857 Author: Hinton Rowan Helper Date of Publication: IF my countrymen, particularly my countrymen of the South, still more particularly those of them who are non-slaveholders, shall peruse this work, they will learn that no narrow and partial doctrines of political or social economy, no prejudices of early education have induced me to write it…We have not breathed away seven and twenty years in the South, without becoming acquainted with the demagogical manoeuverings of the oligarchy. Their intrigues and tricks of legerdemain are as familiar to us as household words; in vain might the world be ransacked for a more precious junto of flatterers and cajolers. It is amusing to ignorance, amazing to credulity, and insulting to intelligence, to hear them in their blattering efforts to mystify and pervert the sacred principles of liberty, and turn the curse of slavery into a blessing. To the illiterate poor whites--made poor and ignorant by the system of slavery--they hold out the idea that slavery is the very bulwark of our liberties, and the foundation of American independence! For hours at a time, day after day, will they expatiate upon the inexpressible beauties and excellencies of this great, free and independent nation; and finally, with the most extravagant gesticulations and rhetorical flourishes, conclude their nonsensical ravings, by attributing all the glory and prosperity of the country, from Maine to Texas, and from Georgia to California, to the "invaluable institutions of the South!" With what patience we could command, we have frequently listened to the incoherent and truth-murdering declamations of these champions of slavery, and, in the absence of a more politic method of giving vent to our disgust and indignation, have involuntarily bit our lips into blisters. The lords of the lash are not only absolute masters of the blacks, who are bought and sold, and driven about like so many cattle, but they are also the oracles and arbiters of all non-slaveholding whites, whose freedom is merely nominal, and whose unparalleled illiteracy and degradation is purposely and fiendishly perpetuated. How little the "poor white trash," the great majority of the Southern people, know of the real condition of the country is, indeed, sadly astonishing. The truth is, they know nothing of public measures, and little of private affairs, except what their imperious masters, the slavedrivers, condescend to tell, and that is but precious little, and even that little, always garbled and one-sided, is never told except in public harangues; for the haughty cavaliers of shackles and handcuffs will not degrade themselves by holding private converse with those who have neither dimes nor hereditary rights in human flesh. B) The Diary of Mary Boykin Chesnut, Circa 1850’s “Like the patriarchs of old our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines, and the mulattos one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children…These wives seem to think that these mulatto children simply drop from the clouds rather than assume that their husbands may have something to do with it” C) 1854; Edgefield, South Carolina; U.S. Senator James Henry Hammond to his son Harry “Louisa’s first child may be mine. I think not. Her second I believe is mine ... Do not let Louisa or any of my children or possible children be the Slaves of Strangers. Slavery in the family will be their happiest earthly condition” D) 1860 Southern slave population-4 million Southern White population-8 million Southern White Slave owners-400,000 E) Document Set #4- NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS, AN AMERICAN SLAVE. Author: Frederick Douglas, 1845 “My new mistress proved to be all she appeared when I first met her at the door,--a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings. She had never had a slave under her control previously to myself, and prior to her marriage she had been dependent upon her own industry for a living. She was by trade a weaver; and by constant application to her business, she had been in a good degree preserved from the blighting and dehumanizing effects of slavery. I was utterly astonished at her goodness. I scarcely knew how to behave towards her. She was entirely unlike any other white woman I had ever seen. I could not approach her as I was accustomed to approach other white ladies. My early instruction was all out of place. The crouching servility, usually so acceptable a quality in a slave, did not answer when manifested toward her. Her favor was not gained by it… Her for having seen her. face was made of heavenly smiles, and her voice of tranquil music. But, alas! this kind heart had but a short time to remain such. The fatal poison of irresponsible power was already in her hands, and soon commenced its infernal work. That cheerful eye, under the influence of slavery, soon became red with rage; that voice, made all of sweet accord, changed to one of harsh and horrid discord; and that angelic face gave Her place to that of a demon. Document Set #3: HOW MISS COW FELL VICTIM TO MR. RABBIT "Uncle Remus." said the little boy, "what became of the Rabbit after he fooled the Buzzard, and got out of the hollow tree?" "Who? Brer Rabbit? Bless yo' soul, honey, Brer Rabbit went skippin' 'long home, he did, des ez sassy ez a jay-bird at a sparrer's nes'. He went gallopin' 'long, he did, but he feel mighty tired out en stiff in his jints, en he wuz mighty nigh dead for sumpin fer ter drink, en bimeby, wen he got mos' home, he spied ole Miss Cow feedin' roun' in a fiel', he did, en he termin' fer ter try his han' wid 'er. Brer Rabbit know mighty well dat Miss Cow won't give 'im no milk, kaze she done 'fuse 'im mo'n once, en w'en his ole 'oman wuz suck , at dat. But never mind dat. Brer Rabbit sorter dance up 'long side er de fence, he did, em holler out: "'Howdy, Sis Cow,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. "'W'y, howdy, Brer Rabbit,' sez Miss Cow sez she. "'How you fine yo'sef deze days, Sis Cow?' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. "'I'm sorter toler'ble, Brer Rabbit; how you come on?' sez Miss Cow, sez she. "'Oh, O'm des toler'ble myse'f, Sis Cow; sorter linger'n' twix' a bauk en a break-down,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. "'How yo' fokes, Brer Rabbit?' sez Miss Cow, sez she. "'Dey er des middlin', Sis Cow; how Brer Bull gittin' on?' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. "'Sorter so-so," sez Miss Cow, sez she. "'Dey er some mighty nice 'simmons up dis tree, Sis Cow,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee, 'en I'd like mighty well fer ter have some un um,' sezee. "'How you gwineter git um, Brer Rabbit?' sez she. "'I 'low'd maybe dat I might ax you fer ter butt 'gin de tree, en shake some down, Sis Cow,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. "C'ose Miss Cow don't wanter diskommerdate Brer Rabbit, en she march up ter de 'simmon tree, she did, en hit it a rp wid'er hawns--blam! Now, den," continued Uncle Remus, tearing off a corner of the plug of tobacco and cramming it into his mouth--"now, den, dem 'simmons wuz green as grass, en na'er one never drap. Den Miss Cow butt de tree--blim! Na'er 'simmon drap. Den Miss Cow sorter back off little, en run agin de tree--blip! No 'simmons never drap. Den Miss Cow back off little fudder, she did, en hi'st her tail on 'er back, en come agin de tree kerblam! en she come so fas', en she come so hard, twel wunner her hawns went spang thoo de tree, en dar she wuz. She can't go forreds, en she can't go backerds. Dis zackly w'at Brer Rabbit waitin' fer, en he no sooner seed ole Miss Cow all fas'en'd up dan he jump up, he did, en cut de pidjin-wing. "'Come he'p me out, Brer Rabbit,' sez Miss Cow, sez she. "'I can't clime, Sis Cow,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee, 'but I'll run'n tell Brer Bull,' sezee; en wid dat Brer Rabbit put out fer home, en 'twan't long 'fo here he come wid his ole 'oman en all his chilluns, en de las' wunner de fambly wuz totin' a pail. De big uns had big pails, en de little uns had little pails. En dey all s'roundid ole Miss Cow, dey did, en you hear me, honey, dey milk't'er dry. De ole uns milk't en the young uns milk't, en den w'en dey done got nuff, Brer Rabbit, he up'n say, sezee: "'I wish you mighty well, Sis Cow. I'd 'low'd bein's how dat you'd hatter sorter camp out all night dat I'd better come en swaje yo' bag,' sezee." "Do which, Uncle Remus?" asked the little boy. "Go 'long, honey! Swaje 'er bag. W'en cows don't git milk't, der bag swells, en youk'n hear um a moanin' en a beller'n des like dey wuz gittin' hurtid. Dat's wat Brer Rabbit done. He 'sembled his fambly, he did, en he swaje ole Miss Cow's bag. "Miss Cow, she stood dar, she did, en she study en study, en strive fer ter break loose, but de hawn done bin jan in de tree so tight dat twuz way 'fo day in de mornin' fo' she loose it. Ennyhow hit wuz endurin' er de night, en atter she git loose she sorter graze 'roun', she did, fer ter jestify 'er stummuck. She 'low'd, ole Miss Cow did, dat Brer Rabbit be hoppin' 'long dat way fer ter see how she gitin' on, en she tuck'n lay er trap fer 'im; en des 'bou sunrise wat'd ole Miss Cow do but march up ter de 'simmon tree en stick her hawn back in de hole? But, bless yo' soul, honey, w'ile she wuz croppin' de grass, she tuck one moufull too menny, laze w'en she hitch on ter de 'simmon tree afin. Brer rabbit wuz settin' in de fence cornder a watchin' 'un 'er. Den Brer Rabbit he say ter hisse'f: "'Heyo,' sezee, 'w'at dis yer gwine on now? Hole yo' hosses, Sis Cow, twel you hear me comin', ' sezee. "En den he crope off down de fence, Brer Rabbit did, en bimeby here he come--lippity-clippitym clippity-lippity-des a sailin' down de big road. "'Mawnin', Sis Cow,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee, 'how you come on dis mawnin'? sezee. "'Po'ly, Brer Rabbit, po'ly,' sez Miss Cow, sez she. 'I ain't had no res' all night,' sez she. 'I can't pull loose,' sez she, 'but ef you'll come en ketch holt er my tail, Brer Rabbit,' sez she, 'I reckin may be I kin fetch my hawn out,' sez she. Den Brer Rabbit, he come up little closer, but he ain't gittin' too close "'I speck I'm nigh nuff, Sis Cow,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. 'I'm a mighty puny man, en I might get trompled,' sezee. 'You do do pullin', Sis Cow,' sezee, 'en I'll do de gruntin',' sezee. "Den Miss Cow, she pull out 'er hawn, she did, en tuck atter Brer Rabbit, en down de big road dey had it, Brer Rabbit wid his years laid back, en Miss Cow wid 'er head down en 'er tail curl. Brer Rabbit kep' on gainin,' en bimeby he dart in a brier-patch, en by de time Miss Cow come 'long he had his head stickin; out, en his eyes look big ez Miss Sally's chany sassers. "'Heyo, Sis Cow! Whar you gwine?' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. "'Howdy, Brer Big-Eyes,' sez Miss Cow, sez she. 'Is you seed Brer Rabbit go by?' "'He des dis minit pass,' sez Brer Rabbit, sezee, 'en he look mighty sick,' sezee. "En wid dat, Miss Cow tuck down de road like de dogs wuz atter 'er, en Brer Rabbit, he des lay doen dar in de brierpatch en roll en laff twel his sides hurtid 'im. He bleedzd ter laff. Fox atter 'im, Buzzard atter 'im, en Cow atter 'in, en dey ain't kotch 'im yit."