List of Abbreviations

advertisement

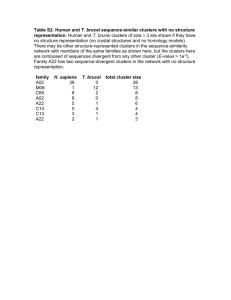

Master Thesis Title of the Master Thesis by Tobias Baeriswyl Unter den Linden 38 1734 Tentlingen Tel. +41/26/555 11 11 Student No.: 01-111-111 supervised by Prof. Dr. Dirk Morschett Chair for International Management Tentlingen, March 13, 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ..................................................................... II 1. Introduction ............................................................................... 1 2. Overview on Cluster Theory .................................................... 2 3. Regional Industry Clusters ...................................................... 3 3.1. Empirical Evidence ..................................................................................... 3 3.2. Typologies of Regional Industry Clusters ................................................ 3 3.2.1. Cluster Typology According To St. John/Pouder ............................... 3 3.2.2. Cluster Typology According To Markusen ......................................... 4 3.3. Players and Elements of Regional Industry Clusters .............................. 6 4. The Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage...... 7 4.1. Factor Conditions ....................................................................................... 7 4.2. Demand Conditions .................................................................................... 7 5. xyz .............................................................................................. 9 6. ABC .......................................................................................... 10 7. The Next Chapter .................................................................... 11 8. Conclusion .............................................................................. 12 Bibliography ................................................................................. 13 List of Interview Partners ............................................................ 14 I List of Abbreviations List of Abbreviations EoS Economies of Scale EMS Electronic Manufacturing Service Provider FDI Foreign Direct Investment Horeca Hotel/Restaurant/Catering I/O Input/Output JV Joint Venture kg kilogramme M&A Merger & Acquisition MNC Multinational Company NID New Industrial District OEM Original Equipment Manufacturer R&D Research & Development SCAE Specialty Coffee Association of Europe SME Small and Medium Sized Enterprise II Introduction 1. 1 Introduction It has long been known that Switzerland, for its relatively small geographic size, has world-leading companies in several different industries. Swiss watch manufacturers, Swiss banks and insurance companies, Swiss chemical and pharmaceutical companies as well as Swiss machine and tools manufacturers are known for their superior quality and reliability. The leading position of Swiss companies in those industries has emerged over different time spans. The emergence of the Swiss watches and banking industries for example dates back to as long as 1700. The Swiss machinery, chocolate and pharmaceutical sectors emerged in the second part of the 19th century and still rank among the most important value creating industries in Switzerland (Borner et al. 1991, pp. 118-120). The fact that Switzerland is one of the world’s most prosperous and competitive countries certainly roots to some degree in the success of firms in the traditional Swiss industries such as banking, pharmaceuticals and machinery. Nevertheless, Switzerland has gained significant worldwide market shares in other, non-traditional Swiss industries as well. Porter (1990, pp. 307-308) and Borner et al. (1991, pp. 103109) identify numerous industries where Switzerland has gained world-class status over the past 50 years. One of the most recent industries where Swiss companies were able to gain world leadership is in the coffee machine business. Even though Switzerland has a long tradition in coffee roasting and blending and Swiss people are known to be heavy coffee consumers, it is not commonly known that Switzerland is the number 1 producer of fully-automatic coffee machines worldwide. Thermoplan, Franke, M.Schaerer, Cafina, HGZ, and Egro are six of the world’s nine largest manufacturers of professional fully-automatic coffee machines. Producers of household and semiprofessional machines such as Jura and Solis complete the world-leading status of Swiss coffee machine manufacturers (Schilliger, 1981, as cited in Krugman, 2014). Whether the concentration of these world-leading companies in a small country like Switzerland is based on pure chance can be questioned. The aim of this thesis is to research the underlying variables behind this impressive dominance of Swiss coffee machine manufacturers. Overview on Cluster Theory 2. 2 Overview on Cluster Theory In times of increasing globalization, transnational companies and flexible production systems, we would expect the importance of firm location to be diminishing. Multinational companies (MNC) have their subsidiaries all over the world. This trend is ascending, since cost of shipping goods is getting ever cheaper. “If anything, the tendency has been to see location as diminishing in importance. Globalization allows companies to source capital, goods and technology from anywhere and to locate operations wherever it is most cost effective. Governments are widely seen as losing their influence over competition to global forces” (Porter 1998, p. 197). Keeping this in mind, why is regional concentration of firms still such an important topic in several fields of study, such as international management, geographic economy or regional development theory? Another popular term to define a geographically co-located group of firms comes from Porter (1990; 1998). Porter was the first author to use the term ‘cluster’. “Clusters are geographic concentrations of interconnected companies, specialized suppliers, service providers, firms in related industries, and associated institutions in particular fields that compete but also cooperate” (Porter 1998, p. 197). A range of similar expressions for the same basic phenomenon emerged and led to some kind of confusion in terminology. “Regional clusters” (Enright 1996; 2000a; 2000b; Hospers/Beugelsdijk 2002), “industrial clusters” (Doeringer/Terkla 1996; Schmitz 2000) and “technology clusters” (St.John/Pouder 2006) are all relating to the same idea. All of these terms, even if they vary in some aspects, have the same underlying assumptions (Malmberg/Sölvell/Zander 1996, p. 86): 1. Regional concentration: A large proportion of total world output of manufactured goods is produced in a limited number of highly concentrated industrial core regions. 2. Spatial clustering: Firms in particular industries or firms that are related in other ways, tend to co-locate and thus form spatial clusters. 3. Path dependence: Both, regional concentration and spatial clustering tend to be persistent over time. Some recent topics in cluster theory contain subjects such as clusters and entrepreneurship (Khan/Ghani 2004; Julien 2007), technology transfer in clusters (Khan/Ghani 2004; St.John/Pouder 2006) and the role of the MNC in fostering regional clusters (Rugman 1998; Rugman/Verbeke 1998; 2001; 2004; Rugman/D’Cruz 2000; Enright 2000b). Regional Industry Clusters 3. 3 Regional Industry Clusters As stated in chapter 2, regional industry clusters contain the three important characteristics of regional concentration, spatial clustering and path dependency (Malmberg/Sölvell/Zander 1996, p. 86). According to Porter (1998, p. 198), the existence of clusters attests that some competitive advantage of the firm can lie outside the company’s direct strategic influence. For companies competing in the environment of regional industry clusters, the location of its business units plays a major strategic role. 3.1. Empirical Evidence In order to identify a cluster, several methods can be applied. First, a purely qualitative study, based on expert interviews and observations can be conducted. Second, an Input/Output (I/O) analysis can be used to understand the most important interdependencies between sectors and to get a first impression of which industry sectors might build a cluster. Quantitative studies make use of multivariate analysis, triangularization and graph theory, descriptive statistics or factor analysis (Czamanski/Ablas 1979, pp. 6265). A more profound explanation of methods and ways for identifying industry clusters follows in chapter 3.5. 3.2. Typologies of Regional Industry Clusters As seen in chapter 2, several authors used different terms to express the tendency of related firms to co-locate in geographic proximity. This following chapter aims to clarify some of the elementary characteristics of various cluster concepts. The first part of this chapter contains a cluster typology that uses the resource-based view as an organizing framework (St.John/Pouder 2006, pp. 141-142). In the second part, a typology using the type of firm configuration, internal and external orientation, and governance structure is presented (Markusen 1996, pp. 293-312). 3.2.1. Cluster Typology According To St. John/Pouder St. John/Pouder (2006, pp. 141-144) use a resource-based view as organizing framework for their cluster typology. They distinguish between two generic types of clusters – technology-based and industry focused. They notice that these two types of regional industry clusters “[…] create very different regional resource profiles over time, accumulate resources in a different manner, cultivate different capabilities, and derive different sources of regional advantage” (St.John/Pouder 2006, p. 141). The main difference between the two concepts is whether the competitive advantage of the cluster firms has its roots in the industry structure (suppliers, labor, key customers, etc.) or in its key technology. For industry clusters key suppliers, distributors or customers, as well as a skilled labor force are the main regional resources. For technology Regional Industry Clusters 4 clusters the main regional resources are technological knowledge of inventors, entrepreneurial insight and research institutions. Furthermore, technology transfer between the cluster members plays a major role in technology clusters (St.John/Pouder 2006, pp. 141-143). Table 1 shows an overview of the two generic cluster types according to St.John/Pouder. Table 1: Differences of Technology and Industry Clusters Cluster Type Technology Clusters Examples Regional Resources Industry Clusters Silicon Valley (California), Austin (Texas) Dalton (Georgia), Detroit (Michigan) Inventors with specific technical knowledge Suppliers, distributors, skilled labor Entrepreneurs with entrepreneurial insight Industry-specific specialists, consultants, service providers Accumulated entrepreneurial experience through support services Institutions such as trade associations Institutions such as universities, research centers, venture capitalists, networking organizations, national labs Sources Competitive Advantage: of Technology transfer capability in the region Diversified markets and applications 1st and 2nd tier suppliers, with related products and services, reduced cost of supply, reduced supply uncertainty Growth Driver New firm formations, spin-offs from existing companies New suppliers, service providers, relocating or new competitor facilities to access available supply network Key Regional Vulnerabilit: Uncertainties and risk of entrepreneurial boom and bust Demand uncertainty of downstream firm/market Tied to the technology lifecycle High dependency of the region upon the economic health of one industry Related diversification, with opportunities for synergy created through shared resources / shared technology Single industry concentration, with some evidence of vertical integration Strategic Analogy Source: Adapted from St. John/Pouder 2006, p.157. 3.2.2. Cluster Typology According To Markusen A second classification of regional industry clusters takes into account the differences in firm configuration, the degree of internal/external orientation and governance structures. In addition to the traditional Marshallian industrial districts (as described by Marshall 1920; Piore/Sabel 1984), this typology introduces three new forms of regional industry clusters. “A hub-and-spoke industrial district, revolving around one or more dominant, externally oriented firms; a satellite platform, an assemblage of unconnected branch Regional Industry Clusters 5 plants embedded in external organization links; and the state-anchored district, focused on one or more public-sector institutions” (Markusen 1996, p. 293). A schematic model of the Marshallian industrial district, the hub-and-spoke district and the satellite platform are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1: Schematic Overview of Cluster Types Marshallian industrial district Hub-and-spoke district Satellite platform Large, locally headquartered firm Small, local firm Branch office, plant Source: Marksuen 1996, p. 297. In Marshallian industrial districts and their extension called the ‘Italianate variant’ of the Marshallian industrial district, small, locally owned companies represent the major players in the cluster. Large local firms and MNCs hardly play any role in the development of a regional industry cluster. Compared to that, in hub-and-spoke districts, the cluster is dominated by one or more large, vertically integrated companies surrounded by suppliers. “Another quite different type of industrial district is present in regions where a number of key firms and/or facilities act as anchors or hubs to the regional economy, with suppliers and related activities spread around them like spokes of a wheel” (Markusen 1996, p. 302). Closely related to this type of regional industry cluster is the definition of the flagship firm “[…] that provides strategic leadership and direction for a vertically integrated chain of business that operate as a coordinated system or network, frequently in competition with similar networks that address the same end markets” (Rugman/D’Cruz 2000, p. 57). The characteristic of the third category – satellite platforms – can be drawn from its name. “In satellite platforms, business structure is dominated by large, externally situated firms that make key investment decisions. […] Minimal intradistrict trade or even conversation takes place among platform tenants. Orders to and commitments to local suppliers are conspicuously absent” (Markusen 1996, p. 304). The fourth distinct cluster category is the state-anchored district. “[…] is what we call the state-anchored district, where a public or nonprofit entity […] is a key anchor tenant in the district. Here, the local business structure is dominated by the presence of such fa- Regional Industry Clusters 6 cilities, whose locational calculus and economic relationships are determined in the political realm, rather than by private-sector firms” (Markusen 1996, p. 306). Table 3.2 shows the four different kind of regional industry clusters described by Markusen (1996). 3.3. Players and Elements of Regional Industry Clusters As seen in the previous chapters a variety of different kind of clusters and different definitions of the cluster concept exist. In order to generalize this information overload, the following chapter provides an overview of the most important players and elements in a regional industry cluster. Instruments are illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 2: The Government’s Cluster Development Instruments Export promotion Collection of economic information Regulatory reform Clusters Development of specialized factors Attraction of foreign FDI Science and technology policy Source: Porter 1998, p. 254. The Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage 4. The Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage 4.1. Factor Conditions 7 In classical trade theory (Heckscher-Ohlin model), differences in production factors are the reason why trade occurs. According to classical trade theory, nations export those goods that make intensive use of the production factors the country is relatively well endowed with. The classical production factors are land, labor and capital. In the diamond model, the role of factor conditions is more complex. “The factors most important to competitive advantage in most industries, especially in the industries most vital to productivity growth in advanced economies, are not inherited but are created within a nation, through processes that differ widely across nations and among industries” (Porter 1990, p. 74). According to Porter (1990, pp. 73-75), factor conditions are to be understood in a much broader way than in the classical model. He distinguishes five categories of factor conditions: Human resources: The quantity, skills and cost of personnel (e.g. skilled labor, cheap labor) Physical resources: The abundance, quality, accessibility and cost of the nation’s land, natural resources and other physical traits such as location relative to other nations or time zones Knowledge resources: The nation’s stock of scientific, technical and market knowledge located in universities, state research institutes, private research facilities, statistical agencies, trade associations and other institutions 4.2. Demand Conditions According to Porter (1990, pp. 86-87), to shape a nation’s competitiveness, the quality of the home demand is much more important than its quantity. Porter notes three attributes of domestic demand that determine national competitiveness in an industry: Composition of domestic demand: The composition of domestic demand influences how firms perceive and react to buyer needs. The segment structure of demand, the sophistication of domestic buyers and the ability to anticipate buyer needs make the composition of the home demand an important element. In general, the more sophisticated and demanding domestic buyers are, the easier it is for a nation to gain competitive advantage. “Nations gain competitive advantage in industries or industry segments where the home demand gives local firms a clearer or earlier picture of buyer needs than foreign rivals can have. Nations also gain advantage if home buy- The Diamond Model of National Competitive Advantage 8 ers pressure local firms to innovate faster and achieve more sophisticated competitive advantages compared to foreign rivals” (Porter 1990, p. 86.). Internationalization of domestic demand: The way home demand conditions pull a nation’s products and services abroad is the third important demand factor influencing national competitive advantage. If domestic customers are mobile or are MNCs they can help establishing overseas presence for the firm. In addition, domestic demand can have an influencing impact on foreign demand (Porter 1990, pp. 97-98). It has to be said that not all elements of home demand are equally important. “The most important attributes of home demand are those that provide initial and ongoing stimulus for investment and innovation as well as for competing over time in more and more sophisticated segments. Examples are especially demanding local buyers, needs that anticipate those of other nations, rapid growth, and early saturation” (Porter 1990, p. 99). As with factor conditions, home demand alone can not guarantee sustainable competitive advantage. Merely the interplay and mutual reinforcement of demand conditions with the other diamond determinants of a nation can build truly sustainable competitive advantage. xyz 5. 9 xyz Chapter 2 with the definition of regional industry clusters already gave a first impression on how important cooperation is. This chapter will start with some theoretical background information on why and how firms actually cooperate. The second subchapter clarifies the phenomenon of co-opetition. This means the simultaneous appearance of competitive and cooperative elements between firms. A comprehensive typology on different cooperation methods, especially the types of alliances forms the last part of chapter 5. As seen in chapter 3, various forms of cooperation exist in regional industry clusters. Having explained the reasons for simultaneous existence of competition and cooperation and the most common motivations for firms to collaborate, the existence of regional industry clusters can be reconstructed from a macroeconomic viewpoint as well as from the perspective of the individual firm. ABC 6. 10 ABC The empirical part in chapters 6-8 will apply the theoretical concepts to the case of the Swiss coffee machine manufacturing industry. In order to obtain the necessary information, several expert interviews were conducted. Two managers of Swiss coffee machine manufacturers (Müller, 09.09.2009; Meier, 08.08.2008) were questioned in guided interviews. The interviews are first used to prove the existence of a Swiss coffee machine manufacturing cluster (as defined in the theoretic chapters) and classify it, in accordance to the typologies. Porter’s diamond model will then be applied to show how Swiss manufacturers were able to gain a competitive advantage in the coffee machine manufacturing industry. At the end, the different forms of cooperation between competitors, suppliers, customers and other cluster participants is highlighted. While the coffee consumption per capita during the last years has largely increased in Luxemburg, it has slightly decreased in Switzerland (Nestlé, 2009). An overview on the per capita coffee consumption development from 2005 until 2007 for selected European countries is provided in table 2. Table 2: Per Capita Coffee Consumption in kg 2005 2006 2007 Luxembourg 11.66 13.49 17.72 Finland 12.6 11.92 12.03 Norway 9.61 9.27 9.91 Denmark 8.80 9.09 8.76 Sweden 7.76 8.69 8.22 Netherlands 7.08 7.80 8.64 Switzerland 8.89 7.51 7.96 Source: Nestlé 2009, p. 111. Regarding the coffee consumption in Switzerland, the Happy Chocolate AG tries to explain this development by the fact that the Swiss hot chocolate consumption per capita is steadily rising. Therefore, the company assumes that hot chocolate may be seen as a substitute of coffee (Smith, 2009a; 2009b). The Next Chapter 7. 11 The Next Chapter Chapter 6 showed the empirical evidence of the Swiss coffee machine manufacturing cluster and its development over time. To know that a cluster exists and how it developed is nice to know and interesting but not enough to give recommendations for cluster players. One should further analyze how strong this cluster is and how national competitive advantage is determined. Porter’s diamond concept is the model that shows how the conditions in the cluster work as a system and how they lead to national competitive advantage for Switzerland in the coffee machine manufacturing industry. Porter (1990, pp. 69-96) notes that national competitive advantage in an industry is determined by factor conditions, demand conditions, related and supporting industries, and the competitive environment in an industry. The three EMS providers Asetronics, Adaxys and Swisstronics share the market for the electronic modules. The electronics module is the central control unit when it comes to operating the coffee machine. A highly reliable electronics unit guarantees the customers that everything in the machine from the grinding degree to the pressure of the pistons and the brewing temperature perfectly fits together and always reaches the desired standards. Most of the software to operate these electronics also comes from Swiss suppliers such as S-Tec (Humbold, 05.05.2015). Conclusion 8. 12 Conclusion The existence of the Swiss coffee machine manufacturing cluster is a unique opportunity for all players involved. Specialized local suppliers accounting for 80-90 % of the manufacturer’s input play an important role. Coordination with the local supplier network is much easier and gives the manufacturers important advantages. Cooperation between manufacturers and suppliers is based on mutual trust and long-term commitment. The high quality of supplier’s raw materials and components is necessary to manufacture the world’s best and most reliable fully-automatic coffee machines. Moreover, the excellent reputation of Swiss machinery, metal processing and electronics companies shaped demand for Swiss coffee machines in an indirect way via the Swiss country image. Customers all over the world associate Swiss coffee machines with quality and reliability, thanks to spill-over effects from these industries. Whether Swiss manufacturers will keep their competitive advantage depends on several factors: Domestic demand, intense rivalry, highly developed engineering and design know-how, cooperation with customers and suppliers, image effects from related and supporting industries, and an overall innovation friendly business climate. These conditions makes it very difficult for foreign competitors to catch up with Swiss manufacturers of fully-automatic coffee machines. If this system of mutually reinforcing determinants can be maintained in the future, Swiss coffee machine manufacturers will remain at the edge of competition. Bibliography 13 Bibliography (not complete, just for illustration) Brandenburger, Adam; Nalebuff, Barry (1995): The Right Game – Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy, in: Harvard Business Review, Vol. 73, No. 4, pp. 57-71. Brandenburger, Adam; Nalebuff, Barry (1996): Co-opetition, New York. Cafina (2008): Cafina Company Profile, http://www.cafina.ch/ kaffeemaschinen.asp?l=en&s=293, accessed on July 1, 2008. Doeringer, Peter B; Terkla, David G (1996): Why Do Industries Cluster?, in: Staber, Udo; Schaefer, Norbert; Sharma, Basu (Eds.): Business Networks – Prospects for Regional Development, Berlin, pp. 175-189. Enright, Michael (2000a): The Globalization of Competition and the Localization of Competitive Advantage – Policies Towards Regional Clustering, in: Hood, Neil; Young, Steven (Eds.): The Globalization of Multinational Enterprise Activity and Economic Development, New York, pp. 303-331. Enright, Michael (2000b): Regional clustering and multinational enterprises – Independence, dependence or interdependence, in: International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 30, No. 2, pp. 114-138 Krugman, Paul (1991): Geography and Trade, Cambridge. Morschett, Dirk (2005): Formen von Kooperationen, Allianzen und Netzwerken, in: Zentes, Joachim; Swoboda, Bernhard; Morschett, Dirk (Eds.): Kooperationen, Allianzen, Netzwerke, 2nd edition, Wiesbaden, pp. 377-403. Nestlé (2009): Coffee Consumption Around the World, Internal Document of Nestlé AG. Smith, Mike (2009a): Chocolate Consumption in Switzerland, Power Point Presentation of Hot Chocolate AG. Smith, Mike (2009b): Chocolate versus Coffee Consumption in Switzerland, Working Paper of Happy Chocolate AG. List of Interview Partners 14 List of Interview Partners Müller, Michael, Director R&D, ABC Machine AG, Bern, Personal Interview, September 9, 2015. Meier, Marc, President, MNO AG, Zurich, Personal Interview, August 8, 2015. Schneider, Paul, Vice-President, Coffee 123, Lausanne, Telephone Interview, August 22, 2015. Zarc, Anna, Head of Business Development, Happy Food AG, Email, July 5, 2015. Affidavit 15