BEYOND COLD WAR POLITICS: - Gettysburg College Alumni Server

advertisement

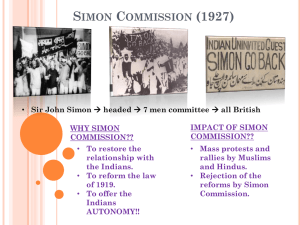

BEYOND COLD WAR POLITICS: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PRESIDENT EISENHOWER AND PRIME MINISTER NEHRU Kaydee Mueller History 412 Eisenhower and His Times December 8, 2008 Mueller 1 On December 9, 1959 President Dwight D. Eisenhower landed in New Delhi, India as part of twenty day tour of eleven nations throughout the Middle East, Europe and Africa. After his arrival, the President, along with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, and Indian President Rajendra Prasad attempted to drive from the airport Presidents house, but the immeasurable crowds of local spectators made this nearly impossible, even bringing the motorcade to a complete standstill mere miles from their destination. This crowd, like others Eisenhower drew during his short trip to India, was numbered upwards of one hundred thousand people, and was some of the largest crowds ever drawn by a foreign dignitary. An on-site National Geographic reporter described the near hysteric crowd—“Friendly crowds, shouting hysterically, surrounded the leaders. Greeters shoved forward to touch Mr. Eisenhower or just his automobile. They crushed fenders, stove in the trunk, and snapped off the radio antenna.”1 Eisenhower was no stranger to attracting large crowds especially after he became an international hero following his World War Two service, but few crowds can compare to those formed by the thousands of Indian citizens who gathered to enthusiastically greet the President of the United States. It is interesting to note that so many of the people of India, a relatively new independent country with strong anti-imperialist sentiments were so enthusiastic in their greetings of the President—a man who maintained a close, personal relationship with the once imperial rulers of India, the British.2 This trip marked an impressive end to a two-term presidency that has left behind many unanswered questions pertaining to his leadership style, his effectiveness as a president, and more specifically, the strange relationship with 1 Gilbert M. Grosvenor, “When the President Goes Abroad: A dramatic pictorial record of Mr. Eisenhower’s 11-nation tour of Asia, Africa and Europe,” National Geographic 117, no. 5 (May 1960): 614. 2 For more information on Eisenhower’s trip abroad in 1959 see Dwight D. Eisenhower, Waging Peace: 1956-1961; The White House Years (Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1965), 486-513. Mueller 2 Prime Minister Nehru, a strict non-alignment proponent whose political views were in strong contrast to the goals of the United States during the Cold War. The eight years during which Dwight D. Eisenhower served as the United States President were a time of unwilling co-existence—democracy and communism, free-trade and controlled economics, Eisenhower and Khrushchev. Both men, like the countries they presided over, lived in a world seemingly divided into two camps, the communist camp and the democratic camp, or to be more specific, the Soviet camp of the U.S.S.R and the Western camp controlled by the Americans. But what many forget to recognize was that a third option very much existed during the Cold War, and it was most often the choice of developing countries recently freed from the constraints of colonial powers. This camp played host to third world countries which chose to focus on national development and thus refused to limit themselves by aligning with only one side of the Cold War. In 1955, non-aligned leaders gained international recognition when, with the help of Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt and Achmed Sukarno of Indonesia, Prime Minister Nehru presented the policy of non-alignment to a coalition of third world countries at the Bandung Conference of Asian and African Nations in Indonesia.3 Unlike his predecessors in the Oval Office, Eisenhower’s presidency was one of constant interaction with the Third World, and as this region consisted of a large proportion of the world population, swaying these non-aligned countries to a western oriented point of view became an essential goal of the Eisenhower administration. Prime Minister Nehru was one of the most important leaders in the Third World, and therefore gained a lot of attention from President Eisenhower, his cabinet and Chester J. Pack Jr., “Thinking Globally and Acting Locally,” in The Eisenhower Administration, The Third World, and The Globalization of the Cold War, eds. Kathryn C. Statler and Andrew L. Johns (Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006), xii-xiii. 3 Mueller 3 advisors.4 Communications with and discussions of the Prime Minister take up a large percentage of the papers detailing the United States foreign relations, and a significant portion of foreign aid was earmarked for his nation. The Eisenhower Administration also had a special interest in India because it was a budding democracy which shared thousands of miles of border with the recently declared People’s Republic of China, a domino fallen into Communist hands. Prime Minister Nehru, on the other hand, recognized that both the Americans and the Soviets would be willing to lend millions, if not billions of dollars of aid with the hopes of wooing India into their respective camps. While his policy did encourage both sides of the Cold War to grant aid and encourage investment in India, this was not an ulterior motive. Though it is easy to see that the Americans and the Soviets both recognized India’s strategic importance and hoped to use aid and investment to convince Nehru to join their bloc, Nehru was not claiming nonalignment to encourage more funding. In fact he often opted to go to the United Nations or to request a loan, in place of direct economic aid or assistance. Nehru, therefore, could not be wooed with the financial prowess of the United States, and it would take much more for President Eisenhower to convince the Prime Minister to lean to the West during the Cold War. The United States and India, as well as their respective leaders did share 4 In the academic world, the relationship between Eisenhower and Nehru often receives some attention, but in respect to Eisenhower, Nehru is simply one of many foreign leaders with who he dealt, and Eisenhower is often mentioned, but only in passing with regards to Nehru’s time in office. In Benjamin Zachariah’s biography of Nehru, President Eisenhower is almost completely forgotten, yet the Prime Minister visited the United States twice, and India received significantly more financial aid than other Third World countries. Burton I. Kaufman acknowledges the aid given to India during the Eisenhower Administration, but does not seem to analyze the importance of the aid or the hopes of improving relations with India, in Trade and Aid. There have been many attempts to understand Eisenhower’s foreign policy towards the Third World since he left office, and many scholars have attempted to analyze the relationship with Nehru as one aspect of a whole. In The Cold War on the Periphery: The United States, India and Pakistan Robert McMahon does mention the visit in 1956 and the success in forging closer ties between the Eisenhower and Nehru, yet again only in passing. It is this theory that I aim to take one step further by developing the relationship past correspondences and the importance of aid, to understanding the personal relationship that developed while the two men met face to face and prompted them to accept one another despite drastically differing on views of international affairs. Mueller 4 more than they would often admit though, and democracy, a dislike for Soviet aggression, and a genuine hope for world peace allowed the two countries, and their leaders to come together and form a working relationship during Eisenhower’s time in the Oval Office. Nehru5 By the time Eisenhower entered the Oval Office in January of 1953, India had been an independent Republic for just three years. After spending many years as a colony of the British Empire, India was attempting the near impossible feat of creating a government while simultaneously eliminating the barriers to development such as religious conflict between Muslims and Hindus, territorial disputes with China and Pakistan, as well as the limits to social interaction controlled by the recently eliminated caste system. In 1946, the Provisional Indian government was sworn in with Nehru as Provisional Prime Minister. The hope of both the British and the Indians was that a provisional government would make the transition of power as smooth as possible. Once India declared official independence in 1950, Nehru was elected to the position of Prime Minister and would serve at this post until his death in 1964. The accomplishments of the Prime Minister are great: he created the world’s largest democracy, instituted plans for economic and industrial development that would make India a leading example for decolonized countries throughout the third world, and he maintained a position of strict non-alignment in the polarized world of the Cold War.6 As the focus of this paper is the 5 To understand the relationship between Eisenhower and Nehru, it is important to explore the development of their political views, the world in which they served and, finally, the development of their personal relationship. To do so, I have tried to divide the paper into corresponding sections. 6 For this section of the paper, I have drawn from the recent bibliography of Nehru by Benjamin Zachariah, whose scholarship seems the most current and lacking in bias. Benjamin Zachariah, Nehru (London: Routledge, 2004), xxi, 118-140. Mueller 5 policy of non-alignment and the relationship between Prime Minister Nehru and the leader of those with whom he would not align, President Eisenhower, it is important to define non-alignment, what it meant to the Prime Minister and how he developed and applied this policy. The Development of Non-Alignment Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Jawaharlal Nehru was building an international reputation as an accomplished statesman and negotiator. He was an early and outspoken anti-colonialist, and became an inspirational leader for Third World countries struggling to gain independence from colonial powers.7 After spending seven years in England, earning a degree from Cambridge and passing the Bar Exam, Nehru returned to India just before the outbreak of World War I. Though the country experienced a few small movements for independence from the Crown, none were nation-wide. The need for independence did not sweep the nation until Gandhi began to lead large, public, peaceful protests against the imperial government. An agrarian movement against the British government had begun, but no one in the cities or the Congress was actually aware of it. It was only with Gandhi’s non-cooperation Movement that “peasants were able to link up with and claim the authority of Gandhi,” and this alliance enabled the movement to become a national phenomenon.8 The influence of Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement on the Indian people, the quest for independence, and, individually on Nehru can not be underestimated. It was also during his time as a young Gandhian that Nehru, like many of India’s educated youth, was “forced to discover and confront the nakedness of 7 8 Ibid., xxi. Ibid., 49. Mueller 6 exploitation and poverty in India.”9 The realization that India was an impressively poor country with a large number of the population illiterate and close to starvation forced the future Prime Minister to realize the countries desperate need for economic and industrial development. This realization would stick with the future Prime Minister, molding his political and social policies for years to come. The Great Depression and World War II marked a period of transition for both India and Nehru. National independence was still the end-goal, but with the distraction of economic crisis and world war, the Britons shelved any possibility of granting Indian independence because the colony provided an ideal market for finished goods, a surplus of raw materials, and an allied front during the War. Finally, in the Post War world, Great Britain was unable to maintain an imperial government and simultaneously rebuild from the damage of World War II, so it was on August 15, 1947 that the viceroy of British India officially left, and the provisional government, with Nehru at it’s head, stepped in. As the Prime Minister of India, Nehru recognized the special role the India would play in the international community. During his tenure in office Nehru experienced the formation of Israel and Pakistan, the decolonization of much of the Middle East, Asia and Africa, the Korean War, the reconstruction of Western Europe, the formation of military alliances such as NATO, SEATO, and the Baghdad Pact, the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Kashmir conflict, and the overarching fluctuation of tensions between the Soviet Union and the Western World. By the time Nehru was chosen as India’s first Prime Minister, his reputation, prestige, and importance as a leader in the third world made India an important strategic goal for both Cold War camps. Though many countries were choosing to align with one side in the Cold War, a select 9 Ibid., 56. Mueller 7 collection of leaders in the Third World choose to follow Nehru’s example and remain uncommitted to either side, choosing instead to focus on national development. When Nehru recognized the desperate poverty, exploitation, and underdeveloped state of his country so many years before, he had inadvertently developed the policy that would influence India’s foreign relations throughout his term. Defining Non-Alignment Once independence was declared India had quite a tumultuous road ahead, filled with nation-building, economic development and industrial expansion. Nehru knew that non-alignment was the best way to focus on national development, avoid military conflict and to create a good reputation for India in the international community. Though many grumbled about his policy at first, the people of India and eventually leaders throughout the Western world would come to realize the necessity of a stance of non-commitment. If Nehru was to get the people of India out of abject poverty he would need the financial support of the international community. Throughout his time as Prime Minister, Nehru consistently preferred the help of the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund to direct aid from the United States or the Soviet Union, but this did not mean he was willing to refuse offers of trade, aid, and agricultural or military tools from independent nations. He also recognized the weakness of the Indian Army, especially when compared with the militaries of the world’s superpowers, and therefore used non-alignment as a means of avoiding military conflict.10 The Prime Minister was determined to achieve political and economic independence as well as social equality for all Indian people. He recognized that the key problems preventing India’s successful development was the economic distribution of wealth and was therefore willing to 10 Ibid., 157. Mueller 8 combing government planning with private investments and capitalistic endeavors, creating a combination of socialist and capitalistic economic policies. He recognized the importance of economics in maintaining the democratic government and understood that if his plans for India’s development failed, the already strong Communist Party of India (CPI) could make significant political gains, and the “Unprecedented Experiment in Democracy” could fail.11 It was from a past of colonial exploitation, the need for development and international support, the desire to avoid of military conflict, and an overall hope for peace that Nehru created non-alignment. In 1965 Krishna Menon described the policy as based on— “(a)non-alignment, (b)support of the freedom of the colonial peoples and (c) opposition to racism,” but they do not fully explain the conduct of contribution of India in world affairs. World peace and co-existence as goals for motivating factors more fully explain a great part of it. Ours is a world in which strife, war and conflict are inherent in the relations between nations. The foreign policy of India does not exclude the use of force or the threat of it…Nationalism plays both a key and conclusive role in our motivations and conduct. Nonalignment is…the policy of independence. It reserves and stoutly maintains that India will make its own decisions in her national interest and in conformity with her ideas of what is good in world interests. It is also a policy based on self-reliance and national dignity.12 He then outlines the Five Principles on which Nehru ideologically based non-alignment The Five Principles are ‘self-interest’ formulations. They are mutual respect, mutual interests, non interference in others’ internal affairs and reciprocity. The very idea or ‘mutuality’ is based on self-respect and self-interest. Not only does respect which is not ‘mutual’ become subservience, but it fails to insure the respect for oneself in which mutuality rest.13 11 Robert Trumbull, “Unprecedented Experiment in Democracy,” New York Times, January 20, 1952. http://proquest.umi.com/pqd (accessed November 29, 2008). 12 V.K. Krishna Menon, “Progressive Neutralism,” in India’s Nonalignment Policy: Strengths and Weaknesses, ed. Paul F. Power (Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1967), 78-79. 13 Ibid. Mueller 9 Menon, like many in the Indian government, was an ardent supporter of the Nehruvian model and was even often viewed as an overly enthusiastic enforcer of non-alignment by foreign governments. His reputation among American politicians was not favorable, as he was prone to much harsher and dramatic statements than those made by the Prime Minister. By 1955, with his government and international reputation more firmly secured than ever, the Prime Minister met with other Third World leaders in Bandung, Indonesia to discuss the development and effective use of non-alignment. India became an example for countries struggling to shake free of colonial powers, as well as those trying to develop politically, socially and economically independent of previous imperialist rulers.14 It is also important to understand that though the Indian government refused to align with one superpower or another, it was by no mean neutral. As Nehru explained “I dislike the world neutrality, because there is a certain passivity about it and out policy is not passive….It [is] a policy which flowed from out past history, from our recent past and from our National Movement and from various ideas that we have proclaimed.”15 Nehru instead remained non-aligned with a particular foreign power so he could interpret each situation as it occurred and respond as best as possible. The Prime Minister believed that by being aligned with a certain power, he would also be limited in his ability to negotiate with others, and that his ultimate goal of world peace would be in jeopardy.16 By 1955, the Indian government was a secure democracy. Nehru had effectively stabilized the state, rationally calmed sectarian forces into coexistence, assumed control over the party, achieved legitimacy for his democratic government and successfully made India the Pack, “Thinking Globally and Acting Locally,” xii-xiii; Zacharian, Nehru, 217-220. T.M.P Mahadevan, “Indian Philosophy and the Quest for Peace,” in India’s Nonalignment Policy: Strengths and Weaknesses, ed. Paul F. Power (Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1967), 1. 16 Ibid., 2. 14 15 Mueller 10 model colony for independent, but struggling, nations within the third world who hoped to develop non-alignment as their foreign policy.17 Eisenhower’s Third World Policy Before Eisenhower actually took office, the fear of Communism was rapidly spreading throughout the Western world, especially the United States. The Truman Doctrine guaranteed American support, especially militarily, to any country attempting to fight against Communist imperialism. By the time Eisenhower took his position as Commander in Chief, the United States was firmly entrenched in the Cold War, and was currently fighting both Korean and Chinese Communist in the Korean War.18 In keeping with his campaign promise to “Go to Korea”, Eisenhower did negotiate an armistice ending the conflict in 1953.19 Peace was not only a term Eisenhower used to win the 1952 election, but it was a goal that was woven throughout his eight years in office. Though he was no stranger to using militaristic means to influence other governments as Zachary Karabell effectively demonstrates in his Architects of Intervention, he does not examine, in detail, the fact that Eisenhower also believed that psychological warfare, financial aid, American investment in foreign nations, and personal diplomacy could convince both foreign leaders and the general public that the United States had their best interest at heart, unlike the evil soviets.20 Aid 17 Zachariah, Nehru, 212-213. It is an interesting, but little known fact, that while peace talks between the Chinese and Americans were at a stand still, it was actually Prime Minister Nehru who, not so discreetly, spread rumors that the Americans were considering nuclear attacks on the Chinese if they did not return to the negotiations. Needless to say, the Chinese were quickly convinced to resume the talks. 19 Philip Geyelin, “I Shall Go to Korea,” Wall Street Journal, October 27, 1952. 20 Zachary Karabell, Architects of Intervention; The United States, the Third World and the Cold War: 1946-1962 (Baton Rouge, LA.: Louisiana State University Press, 1999). 18 Mueller 11 Foreign aid and economic support played a tremendous role during the Eisenhower years, and a significant portion of the money went directly to the third world. Yet many in the Congress were against foreign aid because it did not necessarily guarantee an alliance. As Chester J. Pach emphasizes, “The President urged Congress to approve increased spending on economic aid for Third World countries but he encountered considerable resistance. Eisenhower considered foreign assistance ‘the cheapest insurance in the world’ against the spread of Soviet influence….He challenged the common criticism that foreign aid was nothing more than a ‘giveaway program’.21 The Eisenhower Administration recognized that each country required a policy that was especially designed to incorporate specific political, social and economic variants. In Iran, for instance, when the Shah enjoyed United States support, the popularly elected Dr. Mohammed Mosaddeq was covertly removed from power, despite the seeming contradiction to the democratic policies of the United States.22 While Eisenhower was certainly willing to use the military power of the United States to intervene in foreign affairs, he also recognized when a more peaceful method of intervention could be just as effective. Neutral countries like India and Yugoslavia certainly fell into this category, but the administration often encountered significant resistance from other government branches when requesting aid for non-aligned countries. Though “India’s neutral and nonaligned foreign policy and its program of national economic planning and centralized control alienated many congressmen” Eisenhower “justified economic assistance to India as a means of strengthening the forces of democracy in Asia…and regarded India as the principal test of the theories behind 21 22 Pack, “Thinking Globally and Acting Locally,” xiii. For more details on the CIA’s coup of Mosaddeq see Karabell, Architects of Intervention, 50-91. Mueller 12 development aid.”23 In terms of Yugoslavia, Eisenhower met resistance when proposing aid, but again stoutly defended his proposal by emphasizing “the military and psychological benefits derived from Yugoslavia’s break with the Soviet Union.”24 To the Eisenhower administration, winning the Third World could be done in various ways, and he often incorporated all resources of financial aid, psychological warfare, and military support and personal diplomacy to gain supportive governments and populations. While the long term effects of these decisions has left many countries in unfavorable conditions, Eisenhower’s decision to intervene or provide American aid most often achieved his goals of the time. Tito After World War II Josip Broz Tito declared the Federated People’s Republic of Yugoslavia under the Yugoslav Communist Party and attempted to unite the Yugoslav people under a flag of national pride. President Truman and his advisors were immediately suspicious of the Communist leader, but after his fallout with Stalin and the Soviet Union, Tito became an essential part of the anti-Communist policy in Europe. “By 1947, [an] ‘anticipation of fragmentation within the international communist movement’ led the Truman administration to begin to develop a strategy ‘aimed at driving a wedge’ between the Soviets and their allies.”25 But, before the relationship with the Soviet Union soured, Yugoslavia was considered “fully within the pro-Russian bloc of States” and “increased the opportunity for the Soviets to spread Communism to Italy and Greece.” 26 23 Burton I. Kaufman, Trade and Aid, Eisenhower’s Foreign Economic Policy 1953-1961, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), 69-70. 24 Ibid. 25 Lorraine M. Lees, Keeping Tito Afloat: The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War, (University Park, PA.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 8. 26 Ibid., 9. Mueller 13 After over two years of distrust and friction between the United States and Yugoslavia, the relationship suddenly improved when, in 1948, Stalin and Tito split over Tito’s refusal to acquiesce to Soviet demands to give up his nation’s sovereignty and independence. After the split, the administration recognized that “the split was genuine and that it marked the first substantial challenge to Soviet leadership within the international communist movement [and] led to U.S. assistance for the Tito regime. Tito’s bid for autonomy also represented a destabilizing influence within the bloc…By assisting Yugoslavia; the United States could demonstrate that autonomous communist regimes would receive a cordial welcome in the West.”27 Truman and later, Eisenhower were willing to recognize and support Tito’s independent Yugoslavia because he stood against the Soviet Union, and was therefore a friend to the West. In the way that any friend of the Soviets was an enemy of the United States, for instance the Communist government in China, any enemy of the Soviet Union could be a friend, or at least an associate, of the United States. Tito was often more interested in national issues than in aligning strictly with the West, and because of his stance as a Communist the American government remained suspicious of him, but he was invaluable in the fight against the imperialistic desires of the Communist.28 Once in office, the Eisenhower governments opted to continue Truman’s policy of using Yugoslavia to drive a wedge between the Soviets and the surrounding satellite states of Eastern Europe, as well as to prevent the continued spread of Communism throughout the continent. To do this Eisenhower supplied Tito with tremendous financial and military aid, but unlike his relationship with Nehru, Eisenhower never formed a personal connection with the Yugoslav leader. The 27 28 Idib., 43-44. Ibid., 235-236, Mueller 14 two men coexisted and used each other for personal and national gains, but remained separated by their chosen mode of government, never fully able to accept one another. In India, unlike Iraq and Yugoslavia, the United States Executive Branch recognized and respected the fact that Nehru enjoyed tremendous, almost demigod like popularity and could not simply be pushed out of power. The administration realized that psychological warfare and propaganda alone would not be enough to win the support of the Indian government. Supporters of Nehru, and therefore non-alignment, would not be easily convinced to join the Western fight against Communism, and it would take recognition and respect of the government’s foreign policy to make any progress towards cooperation between the United States and the Indian government. Throughout his first years in office, many in Eisenhower’s administration were confused by Nehru’s stance against aligning. The confusion leaked into public opinion and “Nehru’s position [became] a puzzle to the West.”29 Included in the column is a comic (see Figure one) which clearly illustrates how few in the West understood non-alignment. Thus, the executive branch was forced to get creative, and on the advice of a study of India prepared by the Indian Embassy for the Department of State, began to recognize the importance of respecting India’s government. Make a special effort to treat India as a grown-up in the family of nations. This will involve: (a) Informing the GOI of our readings of facts on important issues by messages to Nehru by the President or the Secretary of State in the most important cases… (b) Informing and as often as possible consulting the GOI in advance on important major moves of general importance…(c) Consulting the GOI in advance on our thinking and proposed action on issues directly affecting India… (d) Show friendliness by accommodating India on small matters of importance to her.30 A.M. Resenthal, “Nehru’s Position a Puzzle to West,” New York Times, January 1, 1956. “India, 1957-1962, A Study,” in et. al. eds. John Glennon, Foreign Relations of the United States, volume viii South Asia 1955-1957, (Washington D.C.: Department of State Publications, 1987), 399. 29 30 Mueller 15 The Eisenhower Administration also recognized that the Indian government had developed a reputation as an important member of the international community and to gain favor with the Indian government, the United States must first offer respect. But still, something was different between the President and Prime Minister, they maintained a special relationship of respect that went beyond politics and was developed primarily through the private talks in Washington D.C. and the Gettysburg Farm. Eisenhower and Nehru: A Lasting Relationship When the relationship between Dwight D. Eisenhower and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru is studied, it is often as part of the larger picture of their time in office, regarding Eisenhower’s approach to the Third World, or Nehru’s policy of nonalignment. Yet, the two men developed an important personal relationship, evident, if nowhere else, in the fact that the Prime Minister holds the special honor of being the only head of state to spend the night at Eisenhower’s personal farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Though the early years of Eisenhower’s presidency proved rocky for the two men, contemporary world events forced the men to recognize that they had more in common than the differences which stood to divide them. The two men were united in their views against Soviet aggression, in their hopes for a successful democracy in India, and most importantly (and idealistically) a hope for eventual and lasting peace. The Early Years Once Eisenhower won the 1952 election and began his eight year tenure as the President of the United States, Prime Minister Nehru had developed a position of almost Mueller 16 total power within India and a reputation as a successful mediator and accomplished diplomat within the international community.31 It is difficult to overstate Nehru’s importance and prestige on the Indian and international scenes...he had unchallenged sway over both the government and the ruling Congress party. As minister of external affairs, he was the principle architect of India’s foreign policy and was intimately involved in managing its diplomacy….Nehru was recognized as the most outstanding figure in the Third World, a major statesman who had become a force to be reckoned with in international affairs.32 With this reputation, it was impossible for the Eisenhower administration to ignore the leader of India, and on a larger scare, the Third World. Unlike his predecessors, Eisenhower was dealing directly with the leaders of newly independent countries throughout the world, and the administration quickly set to gather intelligence and develop programs for this new arena, hoping to enlarge the western sphere of influence against the Soviets. In 1953, an intelligence report on Nehru’s attitude towards Communism suggested that his enthusiasm for Communism had begun to wane, and this could prove valuable to creating anti-Soviet sympathies in the region. “In a confidential conversation with Ambassador Bowles…Nehru reiterated the view that the USSR is presently an aggressor…and even went so far as to state that he fully understood the American position of balancing Soviet forces in Europe.”33 Already, the US government recognized the importance of gaining favor with the Prime Minister because of his status within the Third World, as well as the strategic importance of friendly relations with India due to its geographic location. “The most serious effects of the loss of South Asia to “Probable Developments in South Asia,” in et. al. eds. John Glennon, FRUS, 1952-1954 volume XI, part 2: Africa and South Asia (Washington D.C.: Department of State Publication, 1983), 1074. 32 Howard B. Schaffer, Ellsworth Bunker: Global Troubleshooter, Vietnam Hawk, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 56-57. 33 Research for Near East, South Asia and Africa, “Nehru’s Attitudes Toward Communism, the Soviet Union, and Communist China, No. 6269, Date: July 24, 1953,” in eds. Praveen K. Chaudhry and Martha Vanduzer-Snow The United States and India: A History Through Archives, The Formative Years, (Thousand Oaks, CA.: SAGE Publications, 2008), 295. 31 Mueller 17 Communist control would be psychological and political. It would add to the Soviet Bloc five countries…and would extend Communist control to include nearly half of the world’s population. Loss of South Asia…would greatly reduce confidence in the capacity of the free world to halt the expansion of Communism.”34 India, as the largest democratic nation within South Asia, was clearly crucial in the US plans to prevent the spread of Communism throughout Asia. Despite problems of poverty, low standards of living, religious conflict, and dissatisfaction with the declaration of an independent Pakistan and an increasingly ineffective Congress, American policy makers had high hopes that India would succeed in its quest for democracy.35 More importantly, they recognized that “the continuation of US economic aid would contribute to Indian stability and might encourage a more favorable attitude toward the West…despite its independent and neutral policies, India’s general disposition will probably remain favorable to the West in the East-West struggle.”36 Despite consistent declarations of neutrality by Indian government officials and Nehru himself, American officials remained hopeful that by combining the democratic tendencies of India with economic aid and an increasingly personal relationship between Nehru and Eisenhower, India would continue to lean more towards the West in the politics of the Cold War.37 In attempts to further US-Indian relations upon the recognition of India’s political, economic and strategic importance, both Vice President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles included India on their separate tours of South Asia and Africa, 34 “Consequences of Communist Control Over South Asia,” in FRUS 1952-1954, volume XI, part 2: Africa and South Asia, 1063. 35 “Probable Developments in South Asia,” FRUS 1952-1954, volume XI, 1074-1087. 36 Ibid., 1089. 37 John Foster Dulles, “Memorandum by the Secretary of State to the President: November 30, 1954,” in FRUS 1952-1954, volume XI Africa and South Asia, part 2, 1786. Mueller 18 early in Eisenhower’s time in office. These visits were the first signs that the current administration recognized and respected India’s importance in the international community. Later aims to further the relationship between India and the United States developed as advisors began to suggest that the President invite Nehru to visit the United States in late 1954. As relations between India and the United States continued to deteriorate as a result of disagreements over relations with the Communist government in China, military aid for Pakistan, and military alliances within Southeast Asia, the Assistant Secretary of State for Near East, South Asian and African Affairs drafted the following memorandum— Because of widespread Indian resentment toward these policies of substantial economic aid programs for India and our information and cultural efforts to improve the United States-Indian relations have in a sense become holding operations rather than means of extending our influence. It is entirely possible that the Congress may be tempted in the future to cut India off from special economic assistance…since no significant change to which India objects in likely we should find some means of making those policies more acceptable to India. In my opinion the only way in which that might be done would be through a personal approach of Prime Minister Nehru by President Eisenhower himself… Madame Pandit believes that if Nehru were to spend two days with the President himself in informal surroundings…it might effect a profound change in the Prime Minister’s attitudes toward the United States.38 Though the visit would not come to fruition for over two years, the fact that policy makers began emphasizing the importance of a possible visit by Nehru suggests that they believed the only way to gain Indian support would be to convince the Prime Minister that he and the American President, and by extension, their two nations had much in common. The years between the first recommendation that Nehru visit and the actual trip in “Harold G. Josif and Henry T. Smith, Memorandum by the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Easter, South Asian and African Affairs (Byroade) o the Secretary of State, November 4, 1954”, in FRUS 1952-1954, volume XI Africa and South Asia, part 2, 1772-1773. 38 Mueller 19 December of 1956 were tumultuous times for both the United States and India. While the United States was creating and maintaining the Baghdad and South East Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO), organizing the overthrow of the new President of Guatemala, managing the repercussions from the Supreme Court decisions to uphold Brown v. Board of Education and developing an interstate highway act, India was equally as busy. The relatively new republic was hoping that a Five Year Plan (1951-1955) would jump start agricultural and industrial development, announcing optimism for the spread of nonalignment throughout the recently independent countries of the Third World, attempting to mediate between two superpowers and encouraging the limitation of an arms race, discouraged by Portuguese refusal to return the territory of Goa (a remaining colonial holding dating back to the sixteenth century), hoping to avoid territorial conflict with Communist China through friendly diplomacy and, finally, attempting to mend the rift between itself and the recently declared Pakistan over the region of Kashmir.39 In the summer of 1955, plans to invite the Prime Minister began to take root, but the situation devolved when it was revealed that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev would be visiting India just weeks before the dates intended for Nehru’s trip to the US. American policy makers “did not want to appear to be climbing on the bandwagon of building up Nehru too much.”40 After the Soviet Premiers visit though, popular opinion practically demanded a similar visit to improve US-Indian relationships—“The KhrushchevBulganin tour, in which they also upheld India’s claim to Kashmir against Pakistan while attempting to tar the United States with the colonialist brush, has reinforced the “NSC 5701: Statement of Policy on U.S. Policy Toward South Asia (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Ceylon and Nepal,” FRUS 1955-1957 volume VIII: South Asia, 29-41. 40 “Memorandum for the Assistant Secretary of State for near Eastern, South Asian, and African Affairs (Allen) to the Secretary of State,” FRUS 1955-1957 volume VIII: South Asia, 290. 39 Mueller 20 conviction of responsible Washington officials that the free but neutralist nations of Asia must be handled with special care.”41 That special care called for by The New York Times came in the fore of an official invitation for Nehru to visit the United States in the summer of 1956. While on tour of South Asia, Secretary of States John Foster Dulles stopped in India to extend the Presidents invitation to the Prime Minister. This invitation was seen as an illustration of “the new attention being given to the problem of the ‘uncommitted world’” and would provide the two world leaders with a chance to discuss the issues of non-commitment, India’s nationalistic ambitions, colonial aspirations of the worlds superpowers, and the recognition of Communist China.42 When Nehru accepted the invitation to visit, US-Indian relations were somewhat strained, as the two nations foreign policies continued to clash over the settlement of Kashmir, the return of Goa from the Portuguese government, American involvement in military pacts and India’s relations with the Soviet Union. Though the meeting was originally set for the seventh of July, the two men were forced to reschedule, preferring “to hold their private talks at a time when it was certain no strain would be imposed on the President” during his recuperation.43 As international conflicts arose over the Suez Canal and anti-Soviet uprisings in Hungary the Prime Ministers visit continued to increase in importance because the two heads of state would need to work together to bring peace to the international community. The Visit to the United States 41 Elie Abel, “Dulles Sets Visit to India in March,” New York Times, January 14, 1956. http://proquest .umi.com (accessed on December 2, 2008). 42 “Nehru is Invited to White House: Acceptance Seen,” New York Times, March 15, 1956. http://proquest.umi.com (accessed December 2, 2008). 43 Edwin L. Dale Jr., “Eisenhower, Nehru Postpone Parley,” New York Times, June 26, 1956. http://proquest.umi.com (accessed December 2, 2008). Mueller 21 Though one meeting between world leaders is rarely enough to create stable and lasting bonds that stand the test of domestic and international strife, the meeting between President Eisenhower and Prime Minister Nehru could not have come at a better time to improve relations and help develop a sense of respect and understanding between the two men. On Saturday, December 16, 1956, the Prime Minister arrived for a four day visit to the United States. According to a Presidential Brief developed to prepare Eisenhower for the visit, the United States had five objectives for the visit— (1) To increase Mr. Nehru’s respect and appreciation of the general objectives of American foreign policy, (2) to bring out such broad and significant areas of agreement between the United states and India as the development of broader international cooperation, the need for armament control and inspection safeguards, economic expansion liberties and representative institutions; (3) to ‘agree to disagree’ on those specific foreign policy issues which clearly involve differing Indian and American concepts of national security and national interest, (4) to give a sympathetic hearing to the Prime Minister’s views and make him feel he has been consulted on the problems discussed, and (5) to establish a closer personal relationship between the President and the Prime Minister.44 The Prime Ministers visit, though short was of significant strategic importance to the Eisenhower administration, and if it proceeded smoothly, could tremendously improve United States-Indian relations. Following a meeting with the Secretary of State, the Prime Minister and the President drove to the Eisenhower’s private farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Because the farm was isolated in a small town, but just over an hour north of the Capital, it proved a preferred retreat for the President and it was here where he often engaged in a sort of offhand diplomacy. Visitors to the farm included various American politicians, the vicepresident, French leader Charles De Gaulle, and by the end of 1959, even Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. Though most visits only lasted the afternoon, they proved invaluable “Briefing Paper-Nehru Visit, December 16-20, 1956,” Whitman Files, International Series, Box 28, Folder 1. Eisenhower Library. Accessed at Eisenhower National Historic Site. 44 Mueller 22 in enabling the President to improve personal relationships with various political leaders of his time. Popular opinion, like that of the President and his advisors, suggests that the goal was not to come to any firm decisions regarding domestic of international policies but to simply discuss various issues as means to get to know one another— “No hard decisions are expected for the Eisenhower-Nehru talks,” but it also “no small gain that the elected heads of the world’s two larges democracies have so extensive an opportunity to exchange views and to gain mutual understanding.” 45 Prime Minister Nehru’s visit to the farm deserves special recognition, if for nothing but the fact that he was the only political leader to actually spend the night. While at the farm, the two men spent fourteen hours in private, but relaxed discussion, notably free of ministers of defense and secretaries of state.46 Despite the long talks, the two men also took the time for a public tour the Presidents farm, noting his prized Black Angus cattle herd, and the local battlefields. As their conversations continued back in Washington D.C. the two men dealt in great detail with many issues, most notably, Communist China, India’s policy of neutrality, the uprisings in Hungary, the American position in the Suez crisis, the conflict with Pakistan, and the possibility of continued American aid. Though no treaty was signed and no new programs emerged from the four day trip, it is clear that the leaders of the United States and India had developed a more intimate relationship, and Eisenhower, in particular, had achieved the goal to agree to disagree. I liked Prime Minister Nehru. I deeply sympathize with the agonizing problems that the Chinese aggression later caused his nations. He sincerely wanted to help his people and lead then to higher levels of living and opportunity; I think it only fair to conclude that he was essential to his nation. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru was Chalmers M. Roberts, “Indian Leader Going With Ike to Gettysburg,” Washington Post, December 17, 1956.; “ Mr. Nehru’s Visit”, New York Times, December 20, 1956. http://proquest.umi.com/pqd (accessed on December 2, 2008). 46 Eisenhower, Waging Peace, 108. 45 Mueller 23 not easy to understand; few people are, but his was a personality of unusual contradictions.47 Not only did the meeting have the immediate of signaling to the American and Indian people that the two nations were now on a much friendlier basis, but the effects of the meeting were also seen towards the end of Eisenhower’s term in office, when he reciprocated Nehru’s visit by going to India. Short Term Implications of Nehru’s Visit The timing of Nehru’s visit could hardly have been better, as events in Egypt and Hungary were currently pushing the Prime Minister away from the Soviet Union. Nehru was impressed by the fact that the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Henry Cabot Lodge, had recently “led the move to demand British and French withdrawal from Egypt” instead of refusing to intervene in support of the European allies.48 In addition, the violent repression of Hungarian uprisings by Soviet troops had the Indian Prime Minister reconsidering his stance that, though non-aligned, often leaned slightly towards the USSR. Many speeches given by Nehru in the weeks leading up to his visit suggested that Nehru “had much kinder words for U.S. policy past and present,” as well as overflowing personal tributes for President Eisenhower.”49 As implied by a telegram from the American Ambassador to India just weeks before Nehru’s visit, Nehru came to the United States looking to specifically improve relations. Basic fact is that American prestige is higher than it has been for several years and at a times when India [is] more susceptible to accepting American moral and material leadership as counterweight to UK-Commonwealth ties, loss of prestige of USSR, and uneasy political social and economic rivalry with Red 47 Ibid., 113. Richard H. Rovere, “Letters From Washington,” The New Yorker, December 13, 1956. Gettysburg College Microfilm Collection. 49 “National Affairs,” Time 68 no. 25 (December 17, 1956), 17. Gettysburg College Microfilm Collection. 48 Mueller 24 China….Nehru, therefore, comes to Washington in a sensitive position of weakness. He and his advisers know that they have fumbled internationally, that the UK no longer represents acceptably alternative leadership to US…As consequence, we feel opportunities of personal diplomacy are offered President which could start process of our filling vacuum resulting from loss of prestige by USSR and UK…and of securing greater Indian sympathy with free world, and specifically, US political objectives.50 In a press conference held at the trips conclusion, it was clear that though no important decisions had been made, the two leaders had certainly created the belief that their leaders were now on friendlier terms which would enable cooperation in the future. Multiple news papers reported that though no official political decisions had been made, there was a belief that the two men had reached “a greater understanding” of one another.51 “It can be said that two of the world’s most important leaders know one another better and have a keener appreciation of the problems and aspirations of their respective peoples than they had before.”52 As Nehru told reporters, “‘I think India and American will get along very well in the future in international affairs. When asked if he felt the talked would contribute to world peace, he relied: ‘I certainly do.’”53 The Prime Minister also expressed hope and the belief that Eisenhower now more accurately grasped his policy of non-alignment, and that he as well understood the Presidents international policies, as well as the history behind them. As leaders of the two largest democracies in the world, Prime Minister Nehru and President Eisenhower had many things in common. A desire to see democracy succeed, a strong anti-colonialist view, hopes for India’s economic and social development, a dislike for aggression and Frederic Bartlett, “Telegram from the Embassy in India to the Department of State,” FRUS 1955-1957 volume VIII, South Asia, 320. 51 Warren Rogers Jr., “Ike, Nehru End Four Days of Talks, Announce ‘Greater Understanding,’” Washington Post, December 21, 1956. http://proquest.umi.com/pqd (accessed on December 2, 2008). 52 Cabell Phillips, “Talks with Nehru Typify U.S. Personal Diplomacy,” New York Times, December 23, 1956. http://proquest.umi.com/pqd (accessed on December 2, 2008). 53 Chalmers M. Roberts, “Premier Declares U.S., India Have Reached Better Understanding,” Washington Post, December 20, 1956. http://proquest.umi.com/pqd (accessed on December 2, 2008). 50 Mueller 25 imperialism, and an overall hope for eventual world peace. Though the two men often disagreed over foreign policy, Soviet strategies towards other countries, and the importance of military alliances, Nehru’s visit in the last month of 1956 allowed the two men to develop a working relationship based on common beliefs, rather than those which could divide them. Though a strict anti-Communist throughout his first term in office President Eisenhower had developed a policy that was more accepting and understanding of non-alignment by the time Nehru came to visit. It can not be suggested that Eisenhower would not have simply rather had all non-aligned countries join the western world against the Soviets, but knowing that this was highly unlikely, by meeting Nehru Eisenhower was able to use his charm and good-natured personality to form a lasting bond with the creator and leader of the so called non-committed world. This personal diplomacy that would continue to prove effective throughout Eisenhower’s second term as other world leaders would visit Washington D.C. as well as during his diplomatic trips around the world. The visit of Prime Minister Nehru to Washington D.C. and the Gettysburg Farm presented Eisenhower with the opportunity to cement a relationship that had previously been on shaky foundation. Almost constant differences in opinions created a rift between the two world leaders that appeared almost beyond repair until the seemingly fated visit in December. The combination of a shift in the winds resulting from the Suez Canal crisis and a harsh Soviet reaction to Hungarian protests, common hopes for a peaceful future, and the friendly, impossible not-to-like personality of President Eisenhower transformed the rapport between the two heads of state from one of cool regard to that of friendship and cooperation. When Eisenhower’s final years in office began to come to a close, he Mueller 26 often considered the possibility of an international trip to mark the end of his time served. Visiting the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Northern Africa seemed to be a good final diplomatic step and the “best use of this remaining time for the benefit of the United States.”54Not only did he feel that “face-to-face, friendly discussions offer advantages that can scarcely be realized through written communication,” but he also noted that when foreign heads of state visited the United States they hope to “demonstrate the friendliness of his people toward ours.”55 By visiting eleven countries towards his last days in office, Eisenhower felt he could take advantage of his personal popularity throughout the world to enhance the international reputation of the United States. “‘In every country’ he said ‘I hope to make widely known America’s deepest desire: a world in which all nations may prosper in freedom, justice and peace, unmolested and unafraid.’56” In each country, the American President drew massive crowds, but few were able to compare to the masses that turned out to greet Eisenhower throughout India. The Presidents popularity with the Indian people can be seen in reports from his arrival, his ovation at the Indian Parliament, and most clearly in those detailing the crowd at a civic reception which suggest that over half a million people came to listen to the President and the Prime Minister speak.57 Though his goal was to impress upon the people of the world that the United States was a peaceful and friendly nation, he was also on a diplomatic mission. While in India, the President participated in formal and informal talks with Indian politicians, most often the Prime Minister, and when reflecting upon his final dinner in India the President said—“During the time we spent there I felt closer to Mr. 54 Eisenhower, Waging Peace, 489. Ibid. 56 “ National Affairs,” Time 74 no. 24 (December 14, 1959): 12. 57 Ibid., 503. 55 Mueller 27 Nehru than on any of the other occasions we had been together. He talked of India, her history, her needs, her principle problems, both domestic and foreign and of his hopes for her. His views were palpably honest and sincere….Understandings between our two governments had deepened, I felt, and our ease of communication improved.”58 When Eisenhower began his first term as the President of the United States many believed Prime Minister Nehru would be a proverbial thorn in his side, often leaning towards support of American enemies while simultaneously refusing to align with wither of the two superpowers of the Cold War, but by the time he left office in 1961, Nehru had become both a personal friend to Eisenhower and a political friend to the United States. Though Nehru would never ally with the United States, and insisted on always putting the interests of India before any others, the implementation of personal diplomacy during the visits in 1956 and 1959 allowed Eisenhower to create a bond that, though tested, proved strong enough to withstand future disagreements and international conflict. 58 Ibid., 504. Mueller 28 Figure 1: From A. M. Rosenthal, “Nehru’s Position a Puzzle to West,” The New York Times, January 1, 1956. Mueller 29 Bibliography Primary Sources Briefing Paper-Nehru Visit, December 16-20, 1956.” Whitman Files, International Series, Box 28, Folder 1. Eisenhower Library. Accessed at Eisenhower National Historic Site. John P. Glennon, et. al eds. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955-1957 Volume VIII: South Asia. Washington D.C.: Department of State Publications, 1987 John P. Glennon, et. al eds. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952-1954 Volume XI: Africa and South Asia, Part Two. Washington D.C.: Department of State Publications, 1983 Grosvenor, Gilbert M. “When the President Goes Abroad: A dramatic pictorial record of Mr. Eisenhower’s 11-nation tour of Asia, Africa and Europe.” National Geographic 117, no. 5 (May 1960): 588-650. “National Affairs,” Time 68, no. 25 (December 17, 1956): 17. Gettysburg College Microfilm Collection. “National Affairs.” Time 74, no. 24 (December 14, 1959): 12-17. Gettysburg College Microfilm Collection. Research for Near East, South Asia and Africa “Nehru’s Attitudes Toward Communism, The Soviet Union, and Communist China, No. 6269, Date: July 24, 1953.” In The United States and India: A History Through Archives, The Formative Years, edited by Praveen K. Chaudhry and Martha Vanduzer-Snow, 280-295. Thousand Oaks, CA.: SAGE Publications, 2008. The New York Times. Accessed through Proquest Historical Newspaper Search Engine. Rovere, Richard H. “Letters From Washington.” The New Yorker. December 13, 1956. Gettysburg College Microfilm Collection. The Wall Street Journal. Accessed through Proquest Historical Newspaper Search Engine. The Washington Post. Accessed through Proquest Historical Newspaper Search Engine. Secondary Sources Eisenhower, Dwight D. Waging Peace: 1956-1961; The White House Years. Garden Mueller 30 City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1965. Johns, Andrew L. and Kathryn C. Statler, eds. The Eisenhower Administration, the Third World, and the Globalization of the Cold War. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006. Kaufman, Burton I. Trade and Aid, Eisenhower’s Foreign Economic Policy 1953-1961. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982. Lees, Lorraine M. Keeping Tito Afloat: The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War. University Park, PA.: Pennsylvania State University Press: 1997. Mahadevan, T.M.P. “Indian Philosophy and the Quest for Peace.” In India’s Nonalignment Policy: Strengths and Weaknesses, edited by Paul F. Power, 1-7. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1967. McMahon, Robert J. “Eisenhower and Third World Nationalism: A Critique of the Revisionists.” Political Science Quarterly 101, no. 3 (1986): 453-473. Menon, V.K. Krishna. “Progressive Neutralism.” In India’s Nonalignment Policy: Strengths and Weaknesses, edited by Paul F. Power. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1967. 78-85. Pack Jr., Chester J. “Thinking Globally and Acting Locally.” In The Eisenhower Administration, The Third World, and The Globalization of the Cold War, edited by Kathryn C. Statler and Andrew L. Johns, xi-xxii. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006. Power, Paul F. India’s Nonalignment Policy: Strengths and Weaknesses. Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1967. Schaffer, Edward B. Ellswoth Bunker: Global Troubleshooter, Vietnam Hawk. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. Zachariah, Benjamin. Nehru. New York: Routledge, 2004. Additional Reading Howard, Harry N. “The Regional Pacts and the Eisenhower Doctrine.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 401 (May, 1972): 85-94. Karabell, Zachary. Architects of Intervention; The United States, the Third World and the Cold War: 1946-1962. Baton Rouge, LA.: Louisiana State University Press, 1999. Lodge, Henry Cabot. As It Was: An Inside View of Politics and Power in the ‘50s and ‘60s. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1976. Mueller 31 McMahon, Robert J. The Cole War on the Periphery: The United States, India, and Pakistan. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994. Pruden, Caroline. Conditional Partners: Eisenhower, the United Nations, and the Search for a Permanent Peace. Baton Rouge, LA.: Louisiana State University Press, 1998. Rotter, Andrew J. Comrades at Odds: The United States and India 1947-1964. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000.