Barbarian Settlers, Roman Aristocrats, and

advertisement

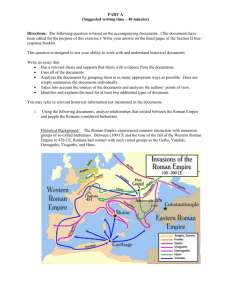

Barbarian Settlers, Roman Aristocrats, and the Foundations of Divided Government in the West Andrew T. Young College of Business and Economics West Virginia University Morgantown, WV 26506-6025 ph: 304 293 4526 em: Andrew.Young@mail.wvu.edu This Version: October 2015 Abstract: I argue that the foundations of effective government constraints in the West can be traced back to the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the settlement of barbarians groups within its frontiers, and the flight of substantial parts of the Roman aristocracy to the Church in the fifth and sixth centuries. These events played out in a way that fortuitously laid the foundations for politically powerful first and second estates – the clergy and landed nobility, respectively – that could provide an effective check on monarchs and, in doing so, bargain for and receive various freedoms, rights, and immunities. JEL Codes: D72, N43, N93, P16 Keywords: governance institutions, checks and balances, economic freedom, first estate, second estate, political economy, ancient economic history, † Prepared for presentation at the “Research on the Origins of Economic Freedom and Prosperity” conference at the Free Market Institute at Texas Tech. I gratefully acknowledge the invitation by Ben Powell to participate and the generous support of the Templeton Foundation in sponsoring the research program. 1 1. Introduction In both principle and practice, classical liberalism is rooted historically in Western Europe. Today this Western European tradition of liberty is still evident. The Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World 2014 Report (Gwartney et al. 2014) scores 101 countries on the extent to which their policies and institutions support “personal choice, voluntary exchange, freedom to enter markets and compete, and security of the person and privately owned property” (p. v). On a scale of 0 to 10, with the latter indicating most free, the average score of Western European countries is 7.51 while the world average is 6.86. Likewise, the average Polity IV (Marshall et al. 2014) democracy score of Western European countries is a 9.81 out of 10 while the world average is only 5.83.1 A score of 10 represents a fully functioning democracy that imposes effective constraints on the executive. This tradition of liberty in Western Europe (henceforth simply the West) has been associated with staggering improvements in standards of living. Western per capita incomes by 1500 were already one third higher than those of Asia and more than twice those of Africa (Madison 2007).2 The divergence of Western incomes accelerated following the Industrial Revolution and by 1950 they were over seven times those of Asia (Parente and Prescott 2000, table 2.1).3 In addition to the undeniable coincidence of liberty and economic progress, numerous 1 Economic Freedom of the World is Gwartney et al. (2014); Polity IV is Marshall et al. (2014). The latest scores available for both correspond to 2012. Given the subject matter of this paper, I use a broad definition of “Western Europe” (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) but do not include Western offshoots. The difference in the Western economic freedom average, in particular, relative to the world is larger if the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand are included. (The average Western economic freedom score is then 7.61). Likewise, the average would also be higher is Greece (economic freedom score of 6.80) is excluded for being a legacy of the Byzantium rather than the West. 2 Voigtländer and Voth (2013) refer to the separation in Western incomes from the rest of the world that began in the Late Middle Ages as the “First Divergence” to distinguish it from the “Great Divergence” (Huntington 1996) in Western incomes associated with the Industrial Revolution and beginning around 1800. 3 Parente and Prescott use data from Madison (1995). 2 empirical studies have shown that the positive link between economic freedom and incomes is robust to controlling for a variety of other potential determinants.4 Why did the tradition of liberty begin specifically in the West? This is a sweeping question. To even begin to address it we first have to hone in on a suitable concept of liberty, including both the economic and political senses of the word. I will conceive of liberty in terms of limited government; where it is constrained in terms of the private resources that it taxes and otherwise expropriates or commands, as well as the extent to which it prevented by doing so without approval by the owners of those resources. This conception of liberty is consistent with the Economic Freedom of the World and Polity IV indices that are referenced above. Working from this conception and conceiving of government as a leviathan (Brennan and Buchanan 1980), liberty exists when there are effective constraints on government. The question that begins this paragraph, then, becomes: Why have Western governments been more constrained than their counterparts in other regions of the globe? I argue that the foundations of effective government constraints in the West can be traced back to the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the settlement of barbarians groups within its frontiers, and the flight of substantial parts of the Roman aristocracy to the Church in the fifth and sixth centuries. These events played out in a way that fortuitously laid the foundations for the estates of the realm. In particular, I will argue that the foundations were laid for politically powerful first and second estates – the clergy and landed nobility, respectively – that could 4 For the positive link between economic freedom and incomes see Ayal and Karras (1998), Dawson (1998), Gwartney et al. (1999), de Haan and Sturm (2000), Heckelman and Stroup (2000), and Young and Sheehan (2014). The Fraser Institute’s index has also been shown to relate positively to health outcomes (Stroup 2007), political freedoms (Lawson and Clark 2010), the extent of trust within a population (Berggren and Jordahl 2006), labor shares (Young and Lawson 2014), and measures of subjective well-being (Ovaska and Takashima 2006; Gehring 2003; Nikolaev 2014). See Hall and Lawson (2014) for a comprehensive survey of empirical studies employing the EFW index as an independent variable. 3 provide an effective check on monarchs and, in doing so, bargain for and receive various freedoms, rights, and immunities. During the Middle Ages the first and second estates were politically formidable groups with distinct interests. Especially during the earlier medieval period their political power was in largest part de facto rather than de jure; based on control over wealth, human capital, administrative infrastructure, and salvation (Acemoglu and Robinson 2006). This de facto political power constrained monarchs’ abilities to extract resources. It compelled them to the constitutional bargaining table (Congleton 2011a). Monarchs could only raise additional taxes by offering to the estates in exchange de jure political rights to complement and reinforce their de facto power. Essentially, monarchs could only untie their hands today in exchange for binding them tomorrow. The importance of de facto politically powerful estates to political and economic freedom in Europe is not a novel idea. My contribution in this paper is to trace the foundations of those estates back to the legal frameworks of fifth century barbarian settlements and the strategies of Romans aristocrats in adapting to their new situations. Most scholars have located the foundations of the estates of the realm in establishment of feudalism, in turn located in the distribution of confiscated Church lands by Charles Martel and the subsequent Carolingian Empire (724-924) (e.g., Hintz 1975, p. 320; Montesquieu 1989, bk. 31, chs. 9-32; Downing 1992, p. 23). The Carolingian developments, including the placitum generale (or general assembly) of the kingdom, were undoubtedly important. However, I argue that these developments built upon fundamental structures that were put in place meaningfully three centuries earlier. 4 In the later part of the fourth century, a nomadic group swept across the Central Asian steppes, over the Black Sea and into Eastern Europe. The aggressive Huns directly or indirectly set into motion the migrations of a number of Germanic barbarian groups that were eventually settled within the frontiers of the Roman Empire. In 376 Goths arrived on the banks of the Danube seeking safe crossing and settlement; around 400 the Vandals moved westward across the Rhine, also in response to Hunnic expansion. The imperial army was distracted by having to manage these barbarian migrations, as well as the Huns’ own invasion of Gaul in 451 (which was ultimately defeated by the Romans with help from Visigothic and other Germanic forces) and by the end of the fifth century large numbers of Franks had also crossed the Rhine and settled themselves in modern Belgium and the Netherlands. One method that the Empire often employed in dealing with militarized barbarian groups was to designate them as federated allies (foederati) and provided with lands, food, and other subsidies in exchange for non-aggression against Rome and/or aggression against the Empire’s enemies (typically imperial usurpers or other barbarian groups). This method was employed frequently during the fifth century with groups such as the Burgundians, Franks, and Visigoths in Gaul; the Vandals in Northern Africa; and the Ostrogoths in Italy. In areas with significant Roman populations, barbarian foederati were settled within the legal framework of hospitalitas (literally, hospitality). Under this framework, each barbarian freeman settler was allotted a specific share of a Roman landowner’s property or a tax assessment share (one third or more) associated with it. The broadly associated a militarized, ascendant barbarian elite with the land. The allotments (sortes) were negotiated and administered by the barbarian military leadership, including the successor kings to the Roman Empire. The barbarian settlers had sworn an oath to 5 their leadership and yet now collectively held a large stake in the productive assets of the realm. I argue that here we see the foundation of the second estate. Settlement with the hospitalitas framework appears to have been minimally antagonistic towards Roman landowners (the aristocracy). Extant Roman literary sources and correspondence do not evidence any significant resistance of revolt against the settlements (supporting Goffart’s (1980) interpretation of the sortes as tax assessment shares; see section 3 below). However, this does not mean that Roman landowners were particularly pleased with their new neighbors and/or tax farmers. Many of these Romans sought new avenues for status and power in what had become an unfamiliar world. Roman aristocrats possessed human capital and a tradition of learning that barbarians sorely lacked. This presented aristocrats with a couple of attractive options. First, literacy and administrative experience were sought-after by the new barbarian kings and their courts became flush with Roman aristocrats. Second, and more relevant to my thesis, many Roman aristocrats entered ecclesiastic offices. The Church provided a hierarchy within which they could leverage their human capital into political power that could offset that of their new barbarian lords. Through the interpretation, development, and communication of doctrine, the Church wielded both the promise of salvation and the threat of damnation. Furthermore, the influx of Roman aristocrats augmented the Church hierarchy with not only wealth but also an extensive network of patron-client relationships. Here we find the groundwork for the first estate. In the remainder of this paper I elaborate on the arguments sketched above. In section 2 I review briefly the role of the estates system in constraining Western governments and establishing a tradition of liberty. Following that review I pursue my thesis that the foundations of the estates system were laid during the decline of the Western Empire and the settlement of 6 the barbarians in the fifth and sixth centuries. In section 3 I discuss the settlement of barbarians within the hospitalitas framework and argue that it resulted in a new militarized and landed barbarian elite that would, moving forward, wield substantial de facto political power. Then in section 4 I discuss how, as a result of the barbarian settlements, many Roman aristocrats took shelter within the Church hierarchy; the result being a transnational hierarchical entity with more administrative capacity than the barbarian successor kingdoms and comparable wealth. A summary and concluding discussion is found in section 5. 2. The Role of the First and Second Estates in Constraining Leviathan The estates system is widely recognized as a defining component of Western medieval exceptionalism. The role the estates of the realm in establishing and furthering a tradition of liberty has been emphasized particularly. Weber (1978, p. 283) notes that: “Historically, the separation of powers in Europe developed out of the old system of estates.” p. Hintz (1975, p. 305) states decidedly: “The representative system of government that today gives the political life of the whole civilized world its distinctive character traces its historical origins to the system of Estates of the Middle Ages.” Downing (1989, pp. 214) argues that the Western “predisposition toward liberal democracy was afforded by four principle characteristics: a rough balance between crown and nobility, decentralized military systems, the preservation in some regions of Germanic tribal customs, and peasant property rights with reciprocal ties to the landlord.”5 In the context of the present discussion, Downing’s emphasis on both the rough balance of power between crown and nobility and decentralized military systems highlights the importance of politically powerful 5 Among the preserved Germanic tribal customs, that of the public assembly likely provided the template for early councils and parliaments. See Young (2015a) for a discussion of Germanic public assemblies during the first centuries BC and AD. 7 second estates. The medieval aristocracy derived de facto political power not only from its claims to the land and the fealty of those who worked it, but also the fact they were militarized. Medieval monarchies essentially desired two things from the aristocracies: military forces and the taxes to pay for them. The aristocracy had both and the monarchies could either bargain for or expropriate them. Doing the latter was costly because one of the very things a monarchy sought from the second estate was the means available for the second estate to rebuff the monarchy. To Downing’s list of characteristics many scholars would add a politically powerful first estate. Mann (1986, p. 379) writes of the Church: [B]y the late eleventh century, [its] ideological-power network was firmly established through Europe in two parallel authoritative hierarchies of bishoprics and monastic communities, each responsible to the pope.[...] Its economic subsistence was provided for by the tithes from all the faithful and by revenues from its own extensive states. The Domesday Book reveals that in 1086 the church received 26 percent of all agricultural land revenues in England, roughly.6 In addition to material wealth, the clergy had human and spiritual capital resources that monarchs desired: “at the political level, bishops and abbots assisted the ruler to control his domains, providing both sacral authority and literate clerics for his chancellery, backing his authority with legitimacy and efficiency” (Mann 1986, pp. 382-383). The first estate could leverage a “communications infrastructure [that] was provided by literacy in a common language, Latin, over which it enjoyed a near monopoly until the thirteenth century” (Mann 1986, p. 379). Furthermore, its monopoly could be used to either aid a monarch in controlling his Downing (1992, p. 20) himself implicitly remarks on the important role of the first estate: “Otto’s [Holy Roman Emperor 962-973] successors were [...] able to build a state with the assistance of the considerable resources of the Church, whose wealth and administrative skills were badly needed.” 6 8 realm or to check his power when his policies ran against Church interests: “Even the worst bandit was wary of excommunication, wished to die absolved, and was willing to pay the church (if not always modify his behavior) to receive it” (Mann 1986, pp. 381-382). Militarized landed aristocracies and a politically powerful Church constrained monarchs’ in important ways. Furthermore, when the estates consented to additional taxies and/or feudal levies it was typically in exchange for various rights, immunities, and freedoms. This is evidenced by “the rise of parliamentary bodies in which monarch, aristocracy, burghers, and clerics determined basic matters, including fundamental ones of taxation and war [...]” (Downing 1992, pp. 21-22). Downplaying the importance of medieval parliaments, Congleton (2011a, p. 2) notes that they were not self-calling: “Kings and queens called ‘their’ parliaments into session whenever convenient and apart from veto power over new taxes, medieval parliaments had very limited authority.” This is true enough, but one needs keep in mind that taxation and war-making were essentially all that medieval monarchies did. Veto power over new taxes was by no means trivial. Similarly, medieval parliaments often vetoed monarchs’ military plans. And as Congleton (2007, 2011a) himself stresses, veto power (along with agenda control) is one of the key chips to bring to the constitutional bargaining table. The rough balance of power between the first and second estates and the monarchs resulted in the “modus vivendi, charters, and legal norms” that proliferated during the Middle Ages: The best known of these is of course the Magna Carta, won by the English baronage at Runnymede. In these arrangements, the principles of magnate representation in the curia regis [king’s court], consultation on matters of taxation, rule of law, and due process were formalized. [...] [P]arallel agreements were hammered out in the Holy 9 Roman Empire at the Diet of Worms (1225), which check the power of the emperor and installed the electoral principle for imperial successions; in Poland with the Pact of Koszyce (1374); and in Sweden with the Land Law of 1350[.] (Downing 1992, pp. 22-23). Here we see de facto political powers that parliaments exercised (more or less effectively, given the time period and monarch) becoming codified into de jure rights. The rough balance of power between monarchs and estates enabled the Church also to effectively pursue its interests, often against those of monarchs. For example, the early medieval Church was able to reform marriage rules in ways that undermined kinship networks and enhanced its own access to inheritances (Goody 1983; Fukyama 2011, ch. 16). Later on, the Church was able to come out on top in the investiture controversy (Fukuyama 2011, ch. 18). There were also peripheral beneficiaries to the rough balance of power between monarchs and estates. These included the nascent “vital commercial centers” of medieval Europe: Towns took advantage of crown-noble antagonisms, played one side against the other, and negotiated crucial freedoms. Burghers gave fixed sums of money [...], artisanal weaponry, and administrative specialists to kings and nobles, and received in exchange fundamental rights, freedoms, and immunities, often stipulated in written charters (Downing 1992, p. 22). These protections from monarchical interference and taxation were undoubtedly critical to establishing the economic freedoms that would later blossom into a thriving commercial society in the West and, ultimately, the Industrial Revolution. 3. The Second Estate: Barbarian Foederati and Hospitalitas 10 To understand how fifth century barbarian settlements laid the foundations for the second estate (i.e., the medieval landed nobility) we first have understand a bit about how those settlements actually occurred. Based on numerous references to “hospitality”, “hosts”, and “guests” that are made in literary sources and barbarian law codes, historians typically refer to the framework for barbarian settlements as hospitalitas. While the exact nature of this framework has been hotly debated, the available evidence – particularly for the Visigoths (418 AD) and the Burgundians (443 AD) in Gaul; and the Ostrogoths (490s AD) in Italy – suggests that settlements “were all regulated operations, presupposing the cooperation of barbarian leaders with the Roman authorities, conducted according to law” (Goffart, 1980, p. 36). The according to law aspect was likely perceived as critical by the Roman authorities. Prior to the fifth century, permanently settling barbarian groups within the imperial frontiers was unheard of. As a matter of public relations it was crucial that the authorities rationalized this break with tradition – one that was surely disturbing to Roman citizens! – as somehow consistent with Roman law (Sivan 1987). The conventional view of hospitalitas is that it was based on Roman law governing the quartering of soldiers (Gaupp 1844; Lot 1928). A barbarian “guest” was granted an allotment (sors) consisting of some fixed share of a Roman “host’s” property. Goffart (1980) forcefully contests this view. He argues that barbarian sortes consisted not of actual property at all. Rather, they were units of the tax assessments associated with Roman property. For various reasons provided below, Goffart’s interpretation of sortes as tax assessment shares is in the main likely correct. However, Sivan (1987) proposes yet another possibility. She argues that laws regarding the settlement of retired soldiers on vacant lands constituted the hospitalitas framework. While this alternative has some appeal in terms of provided a plausible legal fiction, I argue that if it 11 was at all relevant then it was likely only so for barbarian settlements where Roman populations were very sparse (e.g., the Franks in northern Gaul). In a separate paper I explore the economic consequences of hospitalitas (Young 2015c). There I argue that settlement within the hospitalitas framework helped to, on the one hand, align the incentives of Roman elites and barbarian settlers and, on the other hand, realign the incentives of barbarian settlers and barbarian elites. The latter realignment is important to consider in the context of barbarian groups making an organization transition from roving to stationary bandits (Olson 1993; McGuire and Olson 1996; Young 2015b).7 Here I will emphasize that one result of hospitalitas settlement was the establishment of a nascent landed aristocracy constituted by barbarian warrior-settlers. These barbarians were not the elite of their confederacies. Rather, they were rank-and-file freemen who, in being settled, found themselves stakeholders in the productive assets of the realm (i.e., land) on par with the Roman nobility. In Young (2015c) I also argue at some length that Goffart’s (1980) interpretation of barbarian sortes as tax assessment shares is compelling. According to this interpretation of hospitalitas, when a barbarian group was settled within the Western Empire each warrior (and elite member as well) as provided with a claim to one or two thirds (tertiae) of taxes due from a particular Roman landowner. Here I will only mention a couple of his arguments that Goffart makes in favor of this interpretation; arguments that, I my mind, provide strong support for his interpretation. First, Goffart points to terminology that the Roman aristocrat Cassiodorus (writing in the name of King Theodoric) uses in royal correspondence of the sixth century Ostrogothic Young (2015b) provides, in particular, an analysis of “bandits” as organizations and how the collective action problems they face and the shared interests of their members can change during the roving-to-stationary transition. In that I paper I also provide an analytical history of the transition process based on the experience of the Visigothic confederacy in the fourth and fifth centuries. 7 12 Kingdom in Italy. The conventional translation of the relevant text is: “Order all the captains of thousands of Picenum and Samnium to come to our court, that we may bestow the wonted largesse on our Goths” (Cassiodorus 1886, bk. 5, ch. 27, loc. 4983; emphasis added). The “thousands” is a translation of the Latin millenarios. Ostensibly, “thousands” refers to the size of a military unit. However, Goffart (1980, pp. 80-87) argues that in this context the “thousands” (millenarios) is more accurately translated as “holders of millenae”: The most direct proof that the Italian allotments were composed of tax assessment, requiring no dispossession of Roman owners is [when] Theoderic calls the Goths millenari, “holders of millenae” – the millenae begin specifically a unit of tax assessment” (p. 80). Millena was a unit of Roman tax assessment dating back to Diocletian’s reforms: Schedules were drawn up of the various types of assets [...] in such a way that they indicated what quantity of each type of asset “paid in kind (anona)” of one abstract unit of assessment. [...] The millena was a unit of this kind. It was peculiar to Italy, notably to the center and the south, and is first documented in 440 (p. 81). According to Goffart, Theoderic’s Goths were holders of these tax assessment units. A Goth receiving a sors became essentially a tax farmer for his own account. He “bought” the privilege through his military service to Theoderic’s confederacy. Second, Goffart points to the fifth century literary sources and correspondence within which we find a remarkable absence of outrage and/or resistance on the part of Roman landowners. Simply put, Roman aristocrats appear to have taken it too well to be consistent with mass expropriation of one third or more of their actual land. The lack of outrage is more understandable given the tax assessment share interpretation. Post-settlement Roman landowners 13 had to, in effect, merely deal with two tax collectors rather than one.8 Consistent with this lack of evidence, Goffart (1980, pp. 70-71) also points to a letter from the Roman senator Ennodius to a certain Liberius, the patrician tasked with administering the Ostrogothic sortes: You have enriched the countless hordes of Goths with generous grants of land, and yet the Romans have hardly felt it. The victors desire nothing more, and the conquered have felt no loss (Epistolae, 9, 23).9 While Ennodius clearly aims to flatter the patrician, Goffart concurs with Jones (1986 p. 251) that Ennodius “would have hardly introduced the topic at all if it had been a painful one.” If Roman landowners faced expropriation of some large fraction of their actual land, it is difficult to believe that no record of complaint has come down to us. Sivan’s (1987) alternative of land allocations under laws for settling veterans on vacant lands has some appeal. The settled barbarian groups (or at least large elements of them) had all been federated allies (foederati) of the empire at one point or another. Foederati were granted annual subsidies in exchange for maintaining peace with Rome and providing military services against other barbarian groups from without and imperial usurpers from within.10 The applicability of laws pertaining to veterans to federated barbarian groups would have seemed plausibly to Romans. The use of vacant lands would also not have evoked a loud outcry from Roman landowners. However, Sivan never addresses Goffart’s arguments head-on, nor does she explain repeated references in law codes and literary sources to settlements be interactive with Roman landowners. Her alternative may be descriptive, then, of barbarian settlements in sparsely Consistent with this, Goffart points to Theoderic’s (by Cassidorus’ hand) response to complaint from one of his districts. The complaint ostensibly involves the irregular timing of tax collections and Theoderic states: “We have no objection to grant the petition [...] that their [tertiae] shall be collected at the same time as the ordinary tribute. What does it matter under what name the [possessor] pays his contribution, so long as he pays it without deduction?” (Cassidorus 1886, bk. 3, ch. 14, loc. 3252). 9 Translation is from Jones (1986, p. 251). 10 See Young (2015b) for an account of Gothic, and particularly Visigothic, exploits as foederati. 8 14 populated areas (e.g., the Franks in northern Gaul) but probably lacks explanatory power for settlements in more densely populated areas (e.g., the Visigoths and Burgundians in southern Gaul). In her paper, Sivan (1987, p. 769) appears primarily concerned with evaluating what sort of “legal fiction” the empire employed “to conceal a radical departure from past practices” in dealing barbarian groups. Dealing with barbarians as imperial veterans may indeed have been a convenient legal fiction that was promulgated broadly as a means for Rome to save face. Since the settled groups were federated allies, publicizing dealings with them as dealings with imperial veterans could very well have gone hand in hand with hospitalitas. Regardless, what seems clear is that hospitalitas involved allotments of productive assets that were spread broadly (one barbarian settler per Roman landowner) across a region of barbarian settlement. The barbarian sortes were also formulaic: they were spread not only broadly but also equitably in the sense that they were based on predetermined, uniform shares of each Roman possessor’s land. In a panegyric to the same Liberius mentioned above, Cassiodorus (1886, bk. 2, ch. 16, loc. 3632) remarks that hospitalitas “joined both the possessions and the hearts of Goths and Romans alike.” The Roman landowners (nobles) and the barbarian settlers gained a shared interest in productive assets. Assuming that Goffart’s interpretation of hospitalitas is correct, sortes in the form of tax assessment shares were likely more effective than allotments of actual land would have been in aligning Roman and barbarian incentives. Barbarian warriors were not farmers by trade, and even those who had farmed would not have had experience with the large estates of Roman nobles. The barbarians would have likely been ill-suited to realize comparable returns on the land holdings. (This would likely be true even to the extent that sortes included landowners’ 15 bondsmen. Barbarian warriors had no experience managing and monitoring such agents.) Alternatively, under a regime of tax assessment shares the management of land remained in Roman hands while holders of sortes claimed a share of the yield. The sortes “yielded immediate and reliable returns” to the barbarian warriors (Goffart, 1980, p. 54). Broad and equitable allocations of tax assessment shares also would have contributed to something foreshadowing the medieval feudal system. A class a militarized barbarian freemen held claims to the produce of the land. They owed those claims to their leadership: military commanders who had functioned as violent formeteurs (Congleton 2011b) and entrepreneurs at the head of armed retinues (Young 2015a). They owed the equivalent of medieval fealty to their leadership (including their new barbarian kings) and had indeed made their living providing military services under their command. However, the fact remained that the warriors were now direct claimants on the tax base.11 Their interests could and likely did diverge from those their leaders – especially since they were now settled rather than part of a roving bandit with a clearly defined collective purpose – and they wielded military power in support of their interests. The settlement of barbarians within the hospitalitas framework contributed to a drastic change in how European armies were organized and funded relative to the imperial era. Wickham (2009 p. 102) writes: “Beginning in the fifth century, there was a steady trend away from supporting armies by public taxation and towards supporting them by rents derived from private landowning.” For example, following “the end of Ostrogothic Italy, there are no Historian Andreas Schwarcz, in a quoted comment on a paper by Jiménez Garnica (1999), states: “If you get fora long time tax from a land, you tend to think of it as land of your own, and you think of the money you get as a land grant and no longer as taxes, especially when the state becomes weaker.” 11 16 references in the West to army pay, except for rations for garrison, until the Arabs reintroduced it into Spain from the mid-eighth century onwards” (Wickham 2009, p. 103).12 Also: [I]n Frankish Gaul [by] the 580s, assessment registers were no longer being systematically updated, and tax rates may only have been around third of those normal under the empire. Tax, was, that is to say, no longer the basis for the state. For kings as well as armies, landowning was the major source of wealth from now on” (p. 103). The major activity of states, and their largest expense by far, was war-making. The barbarian settlements were the dawn of the feudal era, where states did not tax centrally to pay for professional armies; rather, they called upon landowners for levies of soldiers. Wickham (2009 p. 103) notes that tax-raising states tend to have greater control over their territories than land-based ones. The logic of this statement is clear in the context of fifth and sixth century Western Europe. The barbarian warriors were settled under schemes negotiated and administered by their leadership; and barbarian kings likely made in addition (or additional) distributions of land once their administrations were in place. The warrior-settlers, then, were almost certainly obligated de jure to provide military services to their lords. However, they were de facto the possessors or taxers of the land. Furthermore, they were armed and skilled in the provision of violence. This made them politically powerful. These warrior-settlers were the forerunners of a medieval militarized nobility that wielded considerable bargaining power vis-àvis monarchs. 12 This has to be kept in mind when evaluating the administrations of the barbarian successor kingdoms relative to the Roman Empire that preceded them. Historians regularly note how simplified and allegedly ineffective these states were in their tax systems [CITATIONS]. While this is surely accurate to a greater or lesser extent, one notes that “if the army was landed, the major item of expense in the Roman budget had gone” (Wickham 2009, p. 103). 17 4. The First Estate: Roman Elite as the Keepers of Religion and Learning Hospitalitas served as an effective framework for settling barbarians while aligning their incentives with both their leadership (and now king) and with Roman landowners (Young 2015c). However, while some Roman landowners simply settled into coexistence with their barbarian neighbors/tax collectors, others pursued alternative strategies for survival in the brave new world that confronted them. Those alternative strategies involved Roman nobles leveraging their human capital. One of those strategies would lay the foundations for the first estate. The new barbarian leadership was generally illiterate; they lacked administrative skills and experience in formal jurisprudence. They drew heavily on the Roman nobility for their fledgling governments. Heather (1998, p. 193) remarks upon a portrayal of the mid-fifth century Visigothic court provided by the Gallo-Roman senator, Sidonius Apollinaris: It portrays a king educated in Roman law and literature, who presided over an ordered court, where unruly behavior, especially drunkenness, was not tolerated. Set against traditional Roman prejudices about ‘barbarians’, there is no doubt that Sidonius was signaling to his fellow Roman landowners that the Gothic king was a worthy political ally, who had entered the world of Roman civilization. Implied is the contribution of aristocratic Gallo-Romans to the nascent Visigothic legal tradition.13 Also, nearly all that we know of the working of the sixth century Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy comes to us from royal correspondence written in the name of kings by the Roman aristocrat, Cassiodorus Senator.14 13 14 See also Diaz (1999) and Hen (2011). Cassiodorus published much of this correspondence in his Variae Epistolae (Cassiodorus 1886). 18 By becoming essential components of barbarian administrations and courts, Roman nobles found a way to establish a relationship of mutually beneficial exchange with the barbarian leadership, rather than becoming objects of their extraction (Leeson 2007). Another avenue open to Romans for trade with the erstwhile bandit barbarians was the Church. Most of the settled barbarian groups were Christianized, fully or in large part. This included the Visigoths and Burgundians in Gaul and the Ostrogoths in Italy (Thompson 2008, ch. 4); Clovis the Frank converted after praying to the Christian God during a particularly dicey moment in the Battle of Tolbiac against another barbarian group, the Thuringians (496 or 506; see Gregory of Tours 1974, book 2, ch. 30; Edwards 1988, ch. 4). Sidonius Apollinaris was himself elected to the bishopric of Clermont. He summed up his plight and that of his fellow Romans when, in a reference to tonsure, he declared: “our nobility [must] give up either its homeland or its hair” (Mathisen 2011, loc. 1941). Since Constantine the Great (ruled 306-337) converted to Christianity “high ranking ecclesiastics had been appropriating the perquisites of aristocratic status throughout the empire” (Mathisen 2011, loc. 1965). And since the end of the fourth century aristocrats had themselves been regularly seeking Church offices (Mathisen 2011, loc. 1997). Now, in the fifth and sixth centuries, Roman aristocrats flocked to the clergy. The Roman nobility traditionally associated their status with imperial office holding as well as their noble birth and wealth. One substitute for imperial office was a position in a barbarian court or administration. They also “saw in church office the chance to pursue careers which no longer were available to them in the secular rule” (Mathisen 2011, locs. 2018-2029): The Christian Church hierarchy [...] came to mirror the Empire’s administrative and social structures. Episcopal diocese reflected the boundaries of city territories [...]. 19 Further up the scale, the bishops of provincial capitals were turned into metropolitan archbishops, enjoying powers of intervention in the new, subordinate sees. [...] From 370s onwards, bishops were increasingly drawn from the landowning classes, and controlled episcopal successions by discussion among themselves (Heather 2006, p. 126) As the officials of the state religion, bishops had co-opted certain government functions such as the operation of small-claims courts (Heather 2006, p. 126). Furthermore, church offices suited the aristocrats’ “literary inclinations”: “Cultural and literary achievements which no longer received many, or any, rewards from the state could now lead to advancement in the church” (Mathisen 2011, locs. 2039-2048). With the influx of Roman aristocrats, new wealth and patronage networks augmented the Church’s existing administrative and social infrastructure. Wickham (2009 p. 59) remarks: “the cathedral church by 500 was often the largest local landowner (and therefore patron), and, unlike in the case of private family wealth, its stability could be guaranteed – bishops were not allowed to alienate church property.” This stability was enhanced by the increasing de facto heritability of ecclesiastical offices (Mathisen 2011, locs. 1997-2008). Even in the fifth and sixth centuries, the Church was becoming a politically powerful foil to the expansion of any centralized state: Bishops could exercise virtually monarchical authority in their cities. Their authority, and the kinds of patronage they provided, in many cases vastly exceeded anything that could have been done as saeculares. A bishop, and especially one belonging to an episcopal dynasty, could consolidate property and influence to an extent that no layman could. He had not just individuals, but an entire civitas (city), as his client (Mathisen 2011, locs. 2048-2057). 20 Whereas Roman provincial aristocrats operated extensive patron-client networks, those networks became consolidated in the Church, the institution that also provided for the population’s spiritual well-being. Wealth, extensive patron-client networks, and a sophisticated administrative hierarchy meant that church was poised to become a major political player in medieval Europe: The fact that this institutional structure did not depend on the empire, and was above all separately funded, meant that it could survive the political fragmentation of the fifth century, and the church was indeed the Roman institution that continued with least change into the early Middle Ages (Wickham 2009, p. 59). While bishoprics were essentially “monarchical” in their respective cities, providing checks on centralizing efforts from a subnational level; the identity of Christendom transcended locality and territory, meaning that European states would also have to deal with a supranational check on their powers. Thus we have the beginning of the first estate. 5. Concluding Discussion This paper was motivated by the question: Why did the tradition of liberty begin specifically in the West? Numerous scholars argued that the estates system was an important contributor to the Western tradition of liberty. De facto politically powerful group interests associated with, respectively, the clergy and the landed aristocracy provided an effective check on monarchists. The first and second estates constrained rulers and, in doing so, put themselves in the position to bargain for and obtain various de jure freedoms, immunities, and rights. The novelty in this paper does not involve pointing out the importance of the estates of the realm. Rather, I argue that important foundations for the first and second states are located in 21 the fall of the decline of the Western Roman Empire, the settlement of barbarian groups within its frontiers, and the flight of Roman aristocrats to Church offices in the fifth and sixth centuries. This thesis contrasts with those of other scholars who focus on the developments of the feudal system during the Carolingian Empire (eight to tenth centuries). The hospitalitas framework of barbarian and the absorption of a large part of the Roman aristocracy by the Church have been neglected by scholars in this context. This is most likely due to the paucity of sources for the fifth and sixth centuries relative to those for the later Early and High Middle Ages (Sarris 2004). However, the methods of barbarian settlement were fortuitous to the establishment of a new militarized landed aristocracy. This at a time when the Emperors became no more in the West and were replaced by more precarious Germanic monarchs. As well, the Church – an institution that already emulated imperial administrative infrastructure – absorbed a large amount of Roman wealth and human capital. Why did the tradition of liberty begin specifically in the West? Perhaps the Huns are to thank. 22 References Acemoglu, D., Robinson, J. A. 2006. De facto political power and institutional persistence. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 96, 325-330. Ayal, E. B., Karras, G. 1998. Components of economic freedom and growth: an empirical study. Journal of Developing Areas 32, 327-338. Berggren, N., Jordahl, H. 2006. Free to trust: economic freedom and social capital. Kyklos 59, 141-169. Brennan, G., Buchanan, J. M. 1980. The Power Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Cassiodorus. 1886. The Letters of Cassiodorus: A Condensed Translation of the Variae Epistolae of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (T. Hodgkin, tr.) (Kindle ed.). London, UK: Henry Frowde. Congleton, R. D. 2007. From royal to parliamentary rule without revolution: the economics of constitutional exchange within divided governments. European Journal of Political Economy 23, 261-284. Congleton, R. D. 2011. Perfecting Parliament: Constitutional Reform, Liberalism, and the Rise of Western Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Congleton, R. D. 2011. Why local government do not maximize profits: on the value-added by the representative institutions of town and city governance. Public Choice 149, 187-201. Dawson, J. W. 1998. Institutions, investment, and growth: new cross-country and panel data evidence. Economic Inquiry 36, 603-619. de Haan, J., Sturm, J-E. 2000. On the relationship between economic freedom and economic growth. European Journal of Political Economy 16, 215-241. 23 Diaz, P. C. 1999. Visigothic political institutions. in The Visigoths: From the Migration Period to the Seventh Century (P. Heather, ed.). Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press. Downing, B. M. 1988. Constitutionalism, warfare, and political change in early modern Europe. Theory and Society 17, 7-56. Downing, B. M. 1989. Medieval origins of constitutional government in the West. Theory and Society 18, 213-247. Downing, B. M. 1992. The Military Revolution and Political Change: Origins of Democracy and Autocracy in Early Modern Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Edwards, J. 1988. The Franks. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. Fukuyama, F. 2011. The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Gaupp, E. T. 1844. Die Germanischen Ansiedlungen Und Landtheilungen in Den Provinzen Des Römischen Westreiches. Breslau: Verlage von Joseph Max & Comp. Gehring, K. 2013. Who benefits from economic freedom? unraveling the effect of economic freedom on subjective well-being. World Development 50, 74-90. Goffart, W. 1980. Barbarians and Romans: The Techniques of Accommodation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Goody, J. 1983. The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Gregory of Tours. 1977. The History of the Franks (L. Thorpe, tr.). London, UK: Penguin Books. Gwartney, J., Lawson, R. Holcombe, R. 1999. Economic freedom and the environment for economic growth. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 155, 643-663. 24 Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., Hall, J. C. 2014. Economic Freedom of the World: 2014 Annual Report. Vancouver: Fraser Institute. Hall, J. C., Lawson, R. A. 2014. Economic freedom of the world: an accounting of the literature. Contemporary Economic Policy 32, 1-19. Heather, P. 1998. The Goths. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. Heather, P. 2006. The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hen, Y. 2011. Roman Barbarians: The Royal Court and Culture in the Early Medieval West. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Hintz, O. 1975. The preconditions of representative government in the context of world history. in The Historical Essays of Otto Hintz (P. Gilbert, ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Huntington, S. P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. Jiménez Garnica, A. M. 1999. Settlement of the Visigoths in the fifth century. In (P. Heather, ed.) The Visigoths: From the Migration Period to the Seventh Century. San Marino: Boydell Press. Jones, A. H. M. 1986. The Later Roman Empire 284-602: A Social, Economic, and Administrative Survey (vol. 1). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. Lawson, R. A., Clark, J. R. 2010. Examining the Hayek-Friedman hypothesis on economic and political freedom. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 3, 230-239. Leeson, P. T. 2007. Trading with bandits. Journal of Law and Economics 50, 303-321. Lot, F. 1928. Du régime de l’hospitalité. Revue Belge de Philoligie et d’Histoire 7: 975-1011. 25 Madison, A. 1995. Monitoring the World Economy: 1820-1992. Paris, France: OECD. Madison, A. 2007. Contours of the World Economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Mann, Michael. 1986. The Sources of Social Power: Volume I, A History of Power from the Beginning to A.D. 1760. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., Jaggers, K. 2014. Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2013. Vienna, VA: Center for Systematic Peace. Mathisen, R. 2011. Roman Aristocrats in Barbarian Gaul: Strategies for Survival in an Age of Transition (Kindle ed.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. McGuire, M. C., Olson, M. 1996. The economics of autocracy and majority rule: the invisible hand and the use of force. Journal of Economic Literature 34, 72-96. Montesquieu. 1989. The Spirit of the Laws (A. M. Cohler, B. C. Miller, H. S. Stone, eds.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Nikolaev, B. 2014. Economic freedom and quality of life – evidence from the OECD’s Your better life index. Journal of Private Enterprise 29, 1-31. Ovaska, T., Takashima, R. 2006. Economic policy and the level of self-perceived well-being: an international comparison. Journal of Socio-Economics 35, 308-325. Olson, M. 1993. Dictatorship, democracy, and development. American Political Science Review 87, 567-576. Parente, S. L., Prescott, E. C. 2000. Barriers to Riches. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Silvan, H. 1987. On foederati, hospitalitas, and the settlement of the Goths in A. D. 418. American Journal of Philology 108, 759-772. Stroup, M. D. 2007. Economic freedom, democracy, and the quality of life. World 26 Development 35, 52-66. Thompson, E. A. 2008. The Visigoths in the Time of Ulfila. London, UK: Duckworth and Co. Sarris, P. 2004. The origins of the manorial economy: new insights from late antiquity. English Historical Review 119, 279-311. Weber, M. 1978. Economy and Society (G. Roth, C. Wittich, eds.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Wickham, C. 2009. The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400-1000. London, UK: Penguin Books. Young, A. T. 2015. From Caesar to Tacitus: changes in early Germanic governance circa 50 BC-50 AD. Public Choice (forthcoming) (http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11127-015-0282-7). Young, A. T. 2015. Visigothic retinues: an analytical history of roving bandits that became a non-predatory state. SSRN Working Paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2607309). Young, A. T. 2015. Hospitalitas. Working Paper. Young, A. T., Lawson, R. A. 2014. Capitalism and labor shares: a cross-country panel study. European Journal of Political Economy 33, 20-36. Young, A. T., Sheehan, K. M. 2014. Foreign aid, institutional quality, and growth. European Journal of Political Economy. 36, 195-208. 27