ENGL486 Undergraduate Final Paper

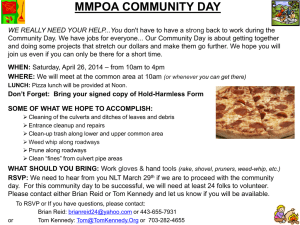

advertisement

Heather Childs Dr. Hanrahan Capstone Paper 4-18-12 1 “Time, Race, and Equality” Tom Robinson in Harper Lee’s 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird is a modern version of Uncle Tom in Uncle Tom’s Cabin published by Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1852. Both Toms are loyal, honest men who do everything they can to help white folks. Tom Robinson is accused of raping Mayella, convicted, and then sent to prison where he is shot while trying to escape. Uncle Tom is beaten because he will not flog an old slave lady. Tom Robinson and Uncle Tom are both betrayed by people they trust. Tom Robinson is betrayed by Mayella and Uncle Tom is betrayed by the Shelbys and the St. Clares. Both Toms are examples of a specific racial archetype: the innocent, subservient, and suffering African-American male. Yet despite these similarities, there are clear differences between the characters—and their reception from critics. Critics have treated these two works differently, often rejecting the racial politics of Uncle Tom’s Cabin while embracing To Kill a Mockingbird, in part because while Stowe focuses on equality based on religion, Lee bases her claims for equality on law and justice. Finally, both books are also written from different points of view. Uncle Tom’s Cabin is written from the view of Stowe while To Kill A Mockingbird is written from the view of a child (Scout). Uncle Tom and Tom Robinson are, in their author’s minds, loyal, honest, and good Christian men who do everything right that is within their power. Those who know them have nothing but good things to say about them. Mr. Shelby, while trying to sell Uncle Tom to Haley says that, “Tom is an uncommon fellow; […] steady, honest, capable, manages my whole farm like a clock” (Stowe 2). He also tells Haley that, “Tom is a good, steady, sensible, pious fellow” (Stowe 2). Haley in turn, when trying to sell Uncle Tom to St. Clare says, that Tom is the “most 2 humble, prayin, pious crittur ye ever did see. Why, he’s been called a preacher in them parts he came from” (Stowe 136). Uncle Tom is so trustworthy that Mr. Shelby sent him to “bring home five hundred dollars” (Stowe 2) and instead of taking the money and running away to Canada, he returned home with all of it. Stowe notes that Uncle “Tom had every facility and temptation to dishonesty; and nothing but an impregnable simplicity of nature, strengthened by Christian faith, could have kept him from it. But, to that nature, the very unbounded trust reposed in him was bond and seal for the most scrupulous accuracy” (Stowe 186). Uncle Tom is so selfless, he tells Aunt Chloe, “If I must be sold, or all the people on the place, and everything go to rack, why, let me be sold. I s’pose I can b’ar it as well as any on’em” (Stowe 36). Lee describes Tom Robinson in similar ways. Reverend Sykes says to his congregation, “You all know of Brother Tom Robinson’s trouble. He has been a faithful member of First Purchase since he was a boy” (Lee 120-121). Atticus says that Tom is, “a member of Calpurnia’s church, and Cal knows his family well. She says they’re clean-living folks” (Lee 75). Scout remarks, “He seemed to be a respectable Negro, and a respectable Negro would never go up into somebody’s yard of his own volition” (Lee 192). Both Toms are betrayed by people who they have done nothing but good for. Uncle Tom is first betrayed by the Shelbys, and is sold by Mr. Shelby to pay off his debts. Mrs. Shelby is against her husband’s decision but there is nothing she can do to prevent it. In her unhappiness with her husband’s decision to sell Tom she says, “I’ll be no accomplice or help in this cruel business. I’ll go see poor old Tom, God help him, in his distress! They shall see, at any rate, that their mistress can feel for and with them” (Stowe 32). Stowe shows that there are good people who want to do what’s right but they fail in taking action and just use their words. Then, Uncle 3 Tom is betrayed by St. Clare when he dies before making Uncle Tom a free man. Mr. Legree is a cruel man who treats all his slaves worse than animals and does not offer them hope. Similarly, Tom Robinson is betrayed by Mayella. He helps her just to be nice and takes no money from her but he is accused of raping and beating her. While Tom is being questioned by Atticus, Scout thinks, “Tom Robinson was probably the only person who was decent to her [Mayella]” (Lee 192). Not only is he accused but he is also convicted when it is obvious that there is no way he could have done what he is being blamed for. What these connections show us, then, is that both Uncle Tom and Tom Robinson embody the common racial archetype of the obedient, subservient black man. They are both innocents who were ruined by selfish/evil people. In To Kill A Mockingbird they call these innocent people who do nothing wrong mockingbirds. Miss Maudie explains, “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird” (Lee 90). Tom Robinson and Uncle Tom both “sing their hearts out for” people who treat them like less then they are. Stowe writes that, “Tom, … had, to the full, the gentle, domestic heart, which, woe for them! has been a peculiar characteristic of his unhappy race” (Stowe 85). Both Toms, no matter how nice and how good they are, will never be treated the way they should. St. Clare says of African Americans that they are, “debased, uneducated, indolent, provoking, -- put, without any sort of terms or conditions, entirely into the hands of such people as the majority in our world are; people who have neither consideration nor selfcontrol” (Stowe 201). 4 Ultimately both Uncle Tom and Tom Robinson are killed, victims of an unjust system that judges by skin color rather than character. Uncle Tom’s faith and the promises that are made to him about being free never come to anything and he is beaten to death by Mr. Legree. Similarly, Calpurnia explains that Tom Robinson gave up hope when they took him to prison. Tom told Atticus that there was no saving him now. Tom decides to try to escape from jail but he is shot and killed. He knows that he will never be proven innocent so he decides to escape or die trying. Atticus says that, “Tom was tired of white men’s chances and preferred to take his own” (Lee 235-236). Both Toms had to rely on white men and they all failed them. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the hopes that people would see how unchristian it is to treat African Americans differently when Christianity makes everyone equal. In other words, Stowe’s primary argument for abolition was a Christian one. Theodore R. Hovet writes, “Stowe believed that when Americans were awakened to the sin of slavery, they would voluntarily abolish the institution” (535). Hovet’s emphasis on “sin”, a religious label, is significant, because in those terms slavery is wrong whether you believe it is a “sin” or unfairness. Stowe, along with other Christian abolitionists, believed that slavery was wrong because when Jesus died on the cross he did away with the old covenant (the ten commandments), which made people slaves to the law and instituted the “voluntary decision of man ‘to love’ Christ because of the qualities He displayed” (Hovet 539). Therefore, Stowe believed that, “slavery violate[d] the spirit of the new covenant because it is based on force rather then love” (Hovet 539). Stowe believed that it was America’s duty to save “all mankind from tyranny” (Hovet 540). The last paragraph of Uncle Tom’s Cabin illustrates Stowe’s beliefs: 5 A day of grace is yet held out to us. Both North and South have been guilty before God; and the Christian church has a heavy account to answer. Not by combining together, to protect injustice and cruelty, and making a common capital of sin, is this Union to be saved, -- but by repentance, justice and mercy; for, not surer is the eternal law by which the millstone sinks in the ocean, than that stronger law, by which injustice and cruelty should bring on nations the wrath of Almighty God! (Stowe 408). Stowe in the above paragraph really emphasizes that if readers did nothing about slavery our salvation was in jeopardy. Stowe lays blame not only on the North and the South for slavery but also the “Christian Church.” In her eyes, an end to slavery meant freedom from “sins” and was only possible through Christian “repentance, justice, and mercy.” Stowe feared that God would send his wrath upon Americans if they continued the way they were. Therefore, as God fearing Christian people, Stowe’s readers should realize that all people are equal and that making people into slaves is unchristian and a sin. Wildly popular in its day, by the 20th century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin fell out of favor with critics who rejected its sentimentalism and problematic theology. Richard Yarborough claims that, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the epicenter of a massive cultural phenomenon, the tremors of which still affect the relationship of blacks and whites in the United States” (Levine 563). Perhaps Stowe’s harshest critic is James Baldwin, who takes her to task for basing her arguments for abolition on a flawed and racist view of Christianity. In “Everybody’s Protest Novel” he writes, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a very bad novel, in its self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality” (533). Baldwin says, “Sentimentality […] is the mark of dishonesty” (533). Baldwin writes that Stowe, “was not so much a novelist as an impassioned pamphleteer; her book was not intended 6 to do anything more than prove that slavery was wrong; was, in fact, perfectly horrible” (533). Baldwin has a problem with Stowe’s characters, especially the alleged benevolent white characters, and the subservient, suffering, slaves. Baldwin also claims that Uncle Tom, who is the only true black man, “has been robbed of his humanity and divested of his sex” (535) and that Uncle Tom’s “triumph is metaphysical, unearthly; since he is black, born without the light, it is only through humility, the incessant mortification of the flesh, that he can enter into communion with God or man” (535). Baldwin is also upset with the fact that Stowe writes Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a way to scare people to be damned to Hell if they do not end slavery. This damnation goes against the “New Covenant” that Stowe believes in, where people have a choice (free will) in whether they follow God or go along with their own desires or wants. Other critics have followed Baldwin’s lead, as shown in an essay by Robert S. Levine. Many African Americans blame Stowe for the cultural consequences they have suffered because of her sentimentalism and racialism (Levine 562). Donald Chaput laments, “the ‘irreparable harm’ done by Stowe’s portrayal of Tom’s Christian resignation; and Addison Gayle Jr. argues that the stereotypical portrayal of Tom and other slaves simply reinforced Southern views of black inferiority and submissiveness” (Levine 562). Anne Moody wrote Coming of Age in Mississippi in 1965. In this autobiography she refers to cowardly, submissive blacks as Uncle Tom’s. Shortly after Moody enters high school she says, “I began to look upon Negro men as cowards. I could not respect them for smiling in a white man’s face, addressing him as Mr. Soand- So, saying yessuh and nossuh” (136). Uncle Tom was the type of man that Moody would have seen as a coward. When Moody goes to Natchez College, she works in the school cafeteria and for a Miss Harris who she calls “the biggest Uncle Tom on campus” (240). In fact, Moody 7 refers to several other people as Uncle Tom’s throughout the book. This way of referring to people remains common even today, indicating just how much readers reject Stowe’s model of an ideal black man. Harper Lee, unlike Stowe, is praised for To Kill a Mockingbird and was given the 1961 Pulitzer Prize in fiction. One of the first reviews appeared in Time Magazine and was positive. Scout, for instance is called, “fiction’s most appealing child since Carson McCuller’s Frankie” (24). R. A. Dave in “The Mockingbird as Symbol” is the first to give To Kill a Mockingbird serious consideration. Dave says, “the title hurts reader’s sensibility and creates an impression that something beautiful is being bruised and broken” (49). Tom Robinson is the “beautiful” person who is “bruised and broken.” According to Dave, the Alabama that Harper Lee writes about, “presents a bleak picture of a narrow world torn by hatred, injustice, violence and cruelty, and we lament to see ‘what man has made of man’” (Dave 51). Such admiration for Lee’s work continues today as the book remains beloved and is frequently taught in schools around the country. A close examination of these reviews and criticisms show that the writers are moved by Lee’s emphasis in law and justice. In Claudia Durst Johnson’s words, To Kill a Mockingbird raises the issue of “the laws of the land and the laws that lie in ‘the secret court of men’s hearts’” (71). Atticus makes the case for Tom Robinson that all men are equal in a court of law. Man’s personal beliefs and prejudices should not hold sway for whether a person is accused of being guilty or innocent. Lee’s novel “presents the argument that the forces that motivate society are not consonant with the democratic ideals embedded in its legal system and that the disjunction between the codes men and women profess and those they live by threatens to unravel individual 8 lives as well as the social fabric” (Johnson 72). Lee provides a further example of such injustice when Helen, Tom Robinson’s wife, cannot find a job, because of what her husband is accused of doing. Tom did not rape Mayella, and yet just being accused of rape causes so much hardship for his family. Once Tom is convicted and sent to jail, this prejudice will only get worse for his family and many readers cry out for justice. In other words, Tom’s death in To Kill A Mockingbird is not a release from his troubles but opens a new world of troubles for his family. In contrast, Stowe’s Uncle Tom embraces death because it is where he’s been heading all along. As he tells George Shelby, “Heaven is better then Kintuck” (381). Lee’s emphasis on secular justice rather than religion is amplified by one of the novel’s key characters, Atticus Finch, the lawyer. Atticus is appointed to represent Tom Robinson and the town folk do not like that he is going to seriously defend him. Scout states, “The court appointed Atticus to defend him. Atticus aimed to defend him. That’s what they didn’t like about it. It was confusing” (Lee 163). Atticus knows the law and knows that everyone is entitled and has the right for a chance to be proven guilty or innocent. Atticus proves Tom’s innocence and that there is no way he could have raped Mayella, but he is declared guilty anyway. Even though it is clear that Tom is innocent, as Judge Taylor said, “People generally see what they look for, and hear what they listen for” (Lee 174). No matter what Atticus would have done, Tom would still have been declared guilty, because he is black. Lee is showing how the legal system and laws are not followed or given to everyone. The decision to convict Tom Robinson is a biased decision based only on the fact that it was a black man versus a white woman. Atticus says in his closing statement, “This case is as simple as black and white” (Lee 203) and he is right. In Tom’s case it is neither probable or 9 believable in what he is accused of doing. Mayella jumped Tom and put him in a real predicament, “he would not have dared strike a white woman under any circumstances and expect to live long, so he took the first opportunity to run – a sure sign of guilt” (Lee 195). Then, when Mr. Gilmer is questioning him, Tom says he was helping Mayella with chores because, “I felt right sorry for her, she seemed to try more’n the rest of’em ---‘ ‘You felt sorry for her, you felt sorry for her?’ Mr. Gilmer seemed ready to rise to the ceiling” (Lee 197). How dare a black man feel sorry for a white woman! By Tom making that statement he was implying that he ‘felt sorry” for someone who was “above” him. Atticus knows that statement was a mistake on Tom’s part and says, “And so a quiet, respectable, humble Negro who had the temerity to ‘feel sorry’ for a white woman has had to put his word against two white people’s” (Lee 204). Atticus in his closing statement really stresses the point that the difference here is black and white; he already knows what the outcome will be, but he wants to fully articulate that the decision will be based on color, “black or white,” not “innocent or guilty.” As Atticus explains, Tom’s guilt should not be based on the color of his skin because “some Negroes lie, some Negroes are immoral, some Negro men are not to be trusted around women --- black or white. But this is a truth that applies to the human race and to no particular race of men” (Lee 204). Atticus closes his statement by saying “there is one way in this country in which all men are created equal […] That institution, gentlemen, is a court” (Lee 205). Atticus demands of the jury to do their duty and send Tom home because he is an innocent man. Thus Atticus and Lee both demand equality based on civil justice, in contrast to Stowe’s pleas based on religion. 10 One final key difference that helps explain readers’ dramatically different responses to the novels is their narrators. The narrator in Uncle Tom’s Cabin is an outside voice that is very adult, certain, and preachy. Stowe’s narrator knows what she believes and is set in her ways; her goal is to make the readers understand what they have done wrong and that it needs to be fixed. The readers do not get attached to Stowe’s narrator because you do not get to know her; she is an outside voice that puts in her beliefs and ideas when she feels it is necessary. Scout, on the other hand, is a child who is trying to understand how people think and why people do and believe the things they do. The readers get to know Scout and sympathize with her. Scout along with her brother Jem, “begin to perceive the complexity of social codes and how the configuration of relationships dictated by or set off by those codes fails or nurtures” (Johnson 75) the characters in To Kill A Mockingbird, especially in the case of Tom Robinson. We see Tom Robinson through Scout’s eyes and she sees him as “a respectable Negro” (Lee 192). Scout’s innocence allows the reader a more clear and un-biased view of the trial and racism. Children have a way of moving people’s hearts in a way that a preachy adult cannot. In conclusion, the similarity between Uncle Tom and Tom Robinson is evident as both embody the archetype of the suffering and innocent black man. Both Toms are African Americans who are treated unfairly and end up getting killed. Uncle Tom is beaten to death for not flogging a fellow slave and Tom Robinson is accused of beating and raping a girl who he was actually treating with respect and went out of his way to help. Both Toms are also let down by the law and white people. This comparison is important because Stowe and Lee’s novels receive very different responses from their readers. Stowe’s focus on religion and slavery being a “sin,” causes her modern readers to not take her seriously and many African Americans blame 11 her for the way whites view them. Lee focuses on the law and how justice is not being shown to those who are innocent and deserve it. Readers also want to listen and believe with Scout, instead of following the preaching of Stowe’s narrator. Though these novels intend to achieve the same goal, Lee’s novel is seen as the greater work and motivates readers to the point where they want to help the Tom’s of the world and further proves that injustice and biased opinions are wrong from every angle and point of view. Works Cited Baldwin, James. “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Ed. Elizabeth Ammons. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2010. 532-539. Print. Dave, R. A. “The Mockingbird as Symbol.” Readings on Harper Lee To Kill a Mockingbird. Ed. Terry O’Neill. California: Greenhaven Press, Inc. 2000. 49-51. Print. Hovet, Theodore R. “The Revolution: Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Response to Slavery and the Civil War.” New England Quarterly 47.4 (Dec. 1974): 535-549. JSTOR. Print. 2-142012. Johnson, Claudia Durst. “The Law of the Land is not the Same as Moral Law.” Readings on Harper Lee To Kill a Mockingbird. Ed. Terry O’Neill. California: Greenhaven Press, In. 2000. 71-83. Print. Lee, Harper. To Kill A Mockingbird. New York: Warner Books, Inc. 1982. Print. Levine, Roberts. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Frederick Douglass’ paper: An Analysis of Reception.” Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Ed. Elizabeth Ammons. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 2010. 562-582. Print. Moody, Anne. Coming of Age in Mississippi. New York: Delta Trade paperbacks. 2004. Print. Stowe, Harriet Beecher., ed. Elizabeth Ammons: Uncle Tom’s Cabin. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010. Print. Time Magazine. “To Kill a Mockingbird is a Wonderful First Novel.” Readings on Harper Lee To Kill a Mockingbird. Ed. Terry O’Neill. California: Greenhaven Press, Inc. 2000. 2324. Print.