Michael Hawley... a life

advertisement

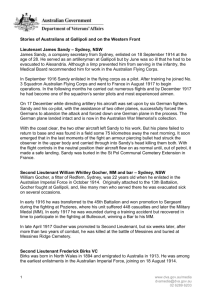

Michael Hawley... a life On my cabinet in the living room at home I have a ‘dead man’s penny’ sitting pride of place and looking down silently on all our daily routines. It is inscribed simply with the name ‘Michael Hawley’. A dead man’s penny is a commemorative medallion presented to surviving relatives of those who lost their lives in the First World War. My grandmother Annie Burnheim (nee Hawley) gave it to me probably because I was the eldest grandchild and I shared my first name with her brother, Michael Hawley, my great uncle. I’ve always felt a connection to the penny but have never sought to understand why until now. Annie was born on the 8th of July 1897 in Morpeth, NSW (near Maitland, just north of Newcastle) the sixth of eight children born to Thomas and Katherine Hawley. Michael was five years older than Annie, born in 1892. The family had been raised on a farm in Morpeth and had moved some time prior to the war to the suburb of Drummoyne in Sydney (44 Cary Street). With the war in full swing, Michael enlisted in the army on 11th of August 1915. The timing is curious as it is four months after the commencement of the Gallipoli campaign and one wonders what news had been filtering back to Australia regarding the progress of that campaign. A sense of duty because things weren’t going so well may have been compelling for so many young men back home. Michael was twenty-three years old, single and on his enrolment form listed his occupation as labourer. I have no surviving photo of Michael but he described himself as five foot, five and half inches tall, of fair complexion, brown hair and blue eyes. By 13th of October 1915, within two months of enlisting, he was on the HMAT Port Lincoln bound for Egypt. Private Michael Hawley, No. 3538, was assigned to the 53rd Battalion of the 5th Australian Division. The 53rd Battalion was raised in Egypt on 14 February 1916 as part of the “doubling” of the Australian Imperial Force. Half of its recruits were Gallipoli veterans from the 1st Battalion, and the other half, fresh reinforcements from Australia. Just think of the stories that must have flowed between the Gallipoli vets and the newbies! The Battalion set off from Alexandria in June 1916 to join the British Imperial Forces fighting on the western front, arriving in Marseilles on 28 June 1916. One can only imagine the absolute wide-eyed awe of the young labourer from Drummoyne as he took in the strange sights of these exotic places half a world away from his family. Fromelles is a small community in the north of France approximately 16 kilometres west of Lille. Fromelles was to be the first major battle by Australian troops on the Western Front. The 5th Division was right in the thick of it and launched their first assault at 6pm on 19 July 1916. They suffered heavy casualties at the hands of German machine gunners and by 8am on 20 July the battle was over with the Division’s dead and wounded numbering a staggering 5,533. The Australian War Memorial reports that Fromelles was the worst 24 hours in Australian history....not the worst in Australian military history, the worst 24 hours in Australia's entire history! The 5,533 casualties suffered in one night was equivalent to the total Australian casualties in the Boer War, Korean War and Vietnam War put together. It was in all respects a staggering military and human disaster. Some personal accounts of that night recalled: “Stammering scores of German machine-guns spluttered violently, drowning the noise of the cannonade. The air was thick with bullets, swishing in a flat criss-crossed lattice of death ... Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid, like great rows of teeth knocked from a comb ... Men were cut in two by streams of bullets [that] swept like whirling knives ... It was the charge of the Light Brigade once more, but more terrible, more hopeless.’ Brigadier General H.E. "Pompey" Elliott. 1 "If you had gathered the stock of a thousand butcher-shops, cut it into small pieces and strewn it about, it would give you a faint conception of the shambles those trenches were," Corporal Hugh Knyvett. Private Michael Hawley, No 3538 was reported missing in action on 19 July 1916 – the first night of his first engagement! The excitement of enlisting, the weeks of preparation, a five month voyage around the world, the nervous anticipation, the chaotic sounds of battle, and the promise of a life all silenced in one split second! No lack of courage but a complete lack of luck in the death lottery that was Fromelles! But for all the unimaginable horror on the battlefields the real horror of not knowing must have been unbearable for the families back home. The Hawleys were notified by the Army in August 1916 that Michael was missing in action. To compound the anxiety for the family, Michael’s elder brother by two years, John Hawley, was also in the service (Private John Hawley, No. 3759). As a member of the Ist battalion he was also wounded on or about 25 July 1916 and admitted to a casualty clearing station with gunshot wounds to the back and right leg. The family would have been advised of John’s wounding around the same time. Annie, my grandmother would have been nineteen, an age to enjoy life not live constantly under the shadow of war. Not knowing what was happening to her older brothers on the other side of the world would have weighed heavily on her mind as well as for the rest of the family. This was at a time when the only communication was by letter – no telephones, let alone smart phones, no internet, no instantaneous connectivity that we take for granted today! Thomas Hawley achingly wrote to “The Defence Department, Melbourne” on 10th March 1917: “I was officially notified on 30 August (that Michael was missing in action) but have heard nothing further from the military. But private letters from the front state that he was badly wounded and sent to England and letters received lately state that he is still in hospital and doing well. Can you give me any information about events leading up to his being “missing” on above date or if your department know anything about events leading up to his being wounded and sent to hospital. Any information you can give will be gratefully received” Mystery surrounds where and how Thomas was receiving this information. Was it from John as he lay in hospital in Rouen, France or when he was transferred to England from February 1917 onwards? Letters from the front, from John or even Michael’s mates, would have taken months to reach home. From the records that remain, one will probably never know how these conflicting accounts materialised. But being 12,000 miles away you can appreciate the family clinging to any shed of hope as Michael was still only reported as missing. It would have been a helpless, gnawing hope just waiting and waiting for any further news… On 2nd of September 1917 a Court of Inquiry conducted in the field pronounced Michael to have been killed in action and his records noted accordingly. The family were formally notified of this in October 1917, after some fourteen months in an information limbo since Michael was first reported missing. Now that their worst fears about Michael had been realised, the family battled to get formal notification of his death. Katherine wrote to the Army on 16th October 1917, “My son no.3538 Pte M Hawley 53rd Battalion was reported missing 19th July 1916 and recently declared killed in action. Will you be good enough to send me certificate of death”. Thomas wrote again on 26 December 1917, “As I want to settle up his affairs would you be good enough to forward to me an official 2 certificate of death”. I note the date of this correspondence is boxing day which probably only serves to highlight the extent to which Michael’s death continued to consume the family’s lives. Curiously, the Grand Secretary of the Grand United Order of Oddfellows, New South Wales wrote to the Army on 3 November 1917 seeking a copy of Michael’s death certificate. Apart from being a great name, ‘the order of oddfellows’, the role that these associations played in a pre-welfare state era is worth a story in itself but that’s for another time. That wasn’t the end of the bad news for the Hawleys though. While John had been wounded in July 1916, he was returned to duty on 20 April 1917. He was wounded in action for a second time on 1 May 1918 and had his leg amputated on 11 May 1918. He was discharged from hospital to return home to Australia in January 1919. Again the sense of helplessness for the family still grieving the loss of Michael and receiving this latest tragic news must have been overwhelming. It was obvious that Thomas (and probably the rest of the family) still struggled with a sense of closure for Michael’s passing. Thomas wrote to the Army in September 1918 seeking any personal effects of Michael, “as I have received nothing belonging to him, could you please inform me if anything has ever been returned as I would like to receive anything however small”. The Army replied on 4 October 1918 that no personal effects have been received at their office to date. The letter further stated: “in view of the fact that this soldier was first reported missing and it was not until sometime later that he was adjudged, as the result of the Court of Inquiry, to have been killed in action, it is considered improbable that any of his personal property was ever recovered.” Just to reinforce the pain of having lost a son into a void without any concrete evidence or any trace of existence, Thomas again wrote to the Army in November 1920, three years after Michael was pronounced killed in action: “I have received no information as to where or how he was killed, nor was anything belonging to him returned. If you can give me any particulars about his death I would be very much obliged”. There is no record of a further response to this request. I’m not sure what they could have said anyway! Katherine was presented with the memorial plaque for Michael in March 1923. Michael’s final resting place is recorded as V.C. Corner Cemetery, Fromelles, which contains the graves of over 400 Australian soldiers who died in the battle and could not be identified. In one of those quirky little coincidences in life, Michael’s battalion, the 53rd Battalion, was officially disbanded on 11 April, 1919. I was born on 11 April 1953! The tragedy of Michael’s story does not require further elaboration. The events speak for themselves and consequences in terms of human loss are obvious. All I know is that on 19 July 2016 I’ll be having a small gathering to toast Michael and to remember a person I never met but somehow still feel acutely for the senseless loss of his young life some one hundred years on. Michael’s gone but certainly not forgotten! Postscript. Annie went on to marry Harold Burnheim in 1920. Harold, my grandfather, had also served and had lost his leg in the war. My grandmother’s war inventory of personal loss was immense: she had lost a brother, had another brother return as an amputee, and married Hal also an amputee and lived with his demons until they later separated. She lived a life irrevocably altered by the impacts of war but, from my memories of her, maintained a quiet dignity that was unshakeable and, although I didn’t appreciate it at the time, inspiring! 3