Ernst - Duke Physics

advertisement

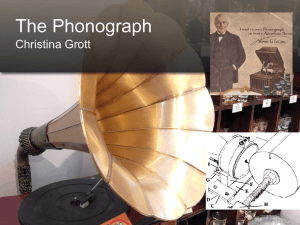

TEMPAURAL MEMORY The role of historicity, recollection, recording and archives in sonic culture [March 31, 2014, Harvard University, Sawyer Seminar Hearing Modernity, session "Aural Memory"] I LISTENING TO MODERNITY WITH MEDIA-ARCHAEOLOGICAL EARS Media archaeology of hearing/listening Re-accessing transient articulations Excursion: Media Archaeology of "Sirenic" sound ["The Song of the Sirens". Experimental setting and theoretical results (Frommolt / Carlé)] II HISTORY OR RESONANCE? THE "SOUND" OF TRADITION A different kind of archive: sonic memory Is there a "sound of the archive"? The (A)Historicity of musical articulation and listening To what degree does the historicity of sound depend on its material embodiment? Modernist spatio-tempor(e)alty: "acoustic space" Enrico Caruso's voice: Remembering past sonospheres by technical media Message or noise? Acoustic archaeology Material entropy versus symbolic endurance of sound recording Sonic memory's two technological embodiments: physical signal and archival symbol III SOUND TECHNICALLY RESCUED FROM THE ARCHIVE Active media archaeology: Sonic revelations (articulation) from the past (Au Claire de Lune) Audio-recordings: Listening to the archive in media-archaeological ways I LISTENING TO MODERNITY WITH MEDIA-ARCHAEOLOGICAL EARS Media archaeology of hearing/listening The very expression "listening to modernity" itself is a to a certain degree already a function of modern sound technologies which go beyond the classic "Pythagorean" hearing (with its strong logocentrisic focus on cosmic order - harmonía -, listening to logos as integer number ratios). In order to arrive at "non-Pythagorean sound" (a term coined by Johannes Kroier, Berlin, in his ongoing dissertation), let us take the notion "media archaeology of listening" literally first, by focusing on the technical media of observation, measuring and recording as active agencies of knowledge on hearing. The loudspeaker as sonifyer has played a crucial role: It was with the invention of the electric telephone and the vacuum tube-based, thus amplifying loudspeaker that previously non-acoustic phenomena (such as small electric currents in human nerves) could be sonified in physiology and other branches of science. The fact that in recent years so-called "cultures of listening" and techniques of sonification have emerged within cultural studies is itself a media-technological effect. In previous centuries, sonic articulation has belonged to the most transitive cultural phenomena, as expressed by the saxophone player Eric Allan Dolphy, Jr.: "When you hear music, after it's over, it's gone, in the air. You can never capture it again."1 The recall of such listening experience depended on actual (and thus always unique) bodily re-encactment. Listening to modern history is a welcome widening by historians of the scope of source material of modernity from writing and visual evidence to past sono-spheres - as aimed at by the World Soundscape Project of Raymond Murray Schaffer and other projects to "archivize" soundscapes of modern life. Still, the framing of this extension still remains within the historical discourse in its (literally) contextualizing gesture. But "discourse analysis cannot be applied to sound archives or towers of film rolls."2 There is another, rather ahistorical type of sound and noise sources - which is close to what humanities and classical studies know since long [have long known] as the archaeological object. Karen Bijsterveld reminds of such limits of historiography: "Hearing the cracks and noises of a phonograph recording may initially enlighten their historical status as 'mechanical' instruments. Yet, the very same sounds complicate our understanding of the 'tone tests' of the early twentieth century in which audiences were unable to hear the difference between performers and records playing [...]. Thus, if we take seriously the historicity of perception, [...] recordings are a far less informative or a much more complex source [...]."3 In terms of the mathematical theory of communication (Claude E. Shannon 1948), such cracks belong to the kind of "noise" introduced by the channel of transmission (here: in the temporal channel). When listening to "ancient" recordings from Edison wax cylinders, nowadays being restored with technomathematical software as digital re-production of sound, we might ask with Michel Foucault (in a slightly different context4): Message or noise? Media-archaeological listening to the sonic past is rather about listening to the technical signifier than to the acoustic or musical signified. Of course, both levels are interlaced; the culturally semantic content of a medium (according to McLuhan) can never be separated from the message of the medium itself. Re-accessing transient articulations Let us extend the understanding of the past to material philology and media-archaeological hermeneutics. At first glance, it looks as if past modes of listening - which vary with cultural history - can only be reconstructed by written descriptions. On the other hand, both past and present ears can be coupled to the same media mechanisms - be it the monochord (Pythagoras), be it the phonograph. For all acoustic or musical experience which depends on machines I introduce the term sonic (in parallel to terms like "electronic"). This common denomina tor, exactly because it is non-human itself, allows for a non-historical immediacy, a gleichursprüngiche (co-original) situation and position. The hard media archaeologic thesis is that the human auditory apparatus is forced to obey laws imposed by the media apparatus; the historicity therefore is deferred by and to the technology. How do we get access to the historicity of sound and hearing? This implies the non-trivial challenge: Can pre-Edison sound(s) be historiographized at all, if they do not exist as historical records?5 The best method to understand a medium is by re-engineering it and its functional (re-)enactment.6 When we re-enact procedure which Pythgoras experimented with the monochord in the 6th century B.C. today, that is: when we pull such a string, we actually re-enact the techno-physical insight of the relation between integer numbers and harmonic musical intervals which once led Greek natural philosophers to muse about the mathematical beauty of cosmic order in general (including the experience and fear of deviation of this aesthetic ideology resulting in the "Pythagorean komma", that is: irrational number relations). Therefore, when we pull the string, we are certainly not in the same historical situation like Pythagoras, since the circumstances, even the ways of listening and the psycho-physical tuning of our ears, is different. But still the monochord is a time-machine in a different sense: It lets us share, participate at the original discovery of musicolgical knowledge, since - in an almost Derridean sense (expressed in his Grammatology) - the original experience is repeatable; the experiment allows for com/ munication across the temporal gap (bridging a temporal, not spatial distance like mass media do). The monochord is a sonic media diagram. Charles Sanders Peirce describes diagrammatic reasoning as such: "Similar experiments performed upon any diagram constructed to the same precept would have the same result."7 Once human senses are coupled with technological settings (media settings), man is within an autopoietic temporal field, a chrono-regime of its own dynamics (or mathematics, when data are registered digitally). Such couplings create moments of literal ex-ception: Man is taken out of the man-made cultural world (Giambattista Vico's definition of "history") and confronts naked physics. The media-electronic equivalent to the vibrations of the monochord string is, of course, the electromagnetic wave. Excursion: Media archaeology of "Sirenic" songs In early April 2004, an academic team from Humboldt University Berlin undertook a sound-archeological research expedition to the Li Galli islands at the Amalfi coast of South Italy. "The basic premise was unqualified trust in the ability of Homer's [...] words to describe Siren songs and a qualified distrust in the ability of human ears to fully understand them. Several experiments involving human organs and technical apparatuses were conducted. On the human side, mouths sung and spoke Homeric verses at and from the islands while human ears listened."8 Does the contemplation of gentle waves with ears heated up by the classical tradition at the Amalfi coast lead to the auditory hallucination of acoustic waves as spatially close and at the same time temporally far away Siren songs, thus constituting a broken "aura" in Walter Benjamin's sense in the aural modality? Let us refer to another sonic water wave setting: The prelude of Richard Wagner's Rheingold opera starts with the natural tonal series (Naturtonreihe) which unfolds rather like a Fourier analysis of superimposed sinus waves (corresponding with the river Rhine itself) than like a musical melody.9 Ernle Bradford who is well known for having tracked Odysseus's naval voyage across the Mediterranean had himself heard the Sirens sing before while serving on H.M.S. Exmoor in early September 1943 carrying out defensive patrols in the Gulf of Salerno in support of a seaborne invasion of the Italian coast. "The music crept by me upon the waters [...]. I cannot describe it accurately, but it was low and somehow distant - a natural kind of singing one might call it, reminiscent of the waves and the wind. Yet it was certainly neither of these, for there was about it a human quality, disturbing and evocative."10 Facing the Amalfi coast south of Naples, the Li Galli islands (Gallo Lungo, Castelluccio and La Rotonda) have been known since antiquity to be home of the Sirens and now served a possible hide-out for enemy vessels. The media-archaeological question is this: It there something like a physically given setting, a grounding in the "real" of signal processing, that kept cultural memory insisting on that place? Referring to such descriptions, Geoffrey Winthrop-Young points out the "grey zone between natural sounds and specifically addressed messages with a 'human quality.' Meaning emerges from noise and reinforces its content by activating a cultural memory of antiquity - a Lacanian transfer from the real (waves) over the symbolic (encoded communication) to the imaginary [...]."11 First of all, Barry Powell's thesis might be suported that between the Iliad and the Odyssey lies the invention of the Greek alphabet, i. e.: the adding of vocal symbols to the syllabic Phenician alphabet in order to record the musicality of oral poetry.12 The sirens are expressions of this vocality. A media archaeology of acoustics in the Odyssey has to confront an (a)historic dilemma: How can an acoustic event which is supposed to have happened before the age of gramophonic recording be verified? The Siren songs in Homer’s Odyssey have long been treated as a mere culturalpoetical invention by the bard. In contrast, this paper gives details of a research project which tries to test and reconstruct such acoustic events by media-archaeological means — a sound political provocation to philological methodologies and visual studies. This can be re-formulated in terms of Julian Jaynes.13 "Sound politics" in Homer’s time meant gaining control over authoritarian verbal hallucinations via the adoption of writing as a sound-technology driven by symbolically reproducible vowels. As cultural technique, "acoustic" writing and sound reading of the sonosphere of language mediated by the phonetic alphabetic code remodeled our bicameral mind becoming conscious. 14 Then, why is it exactly t w o sirens who, as expressed in Homer's Odyssey by the grammatical casus dualis, sang to Ulisses? A mediaarchaeological investigation on the site of the Li Galli islands opposite the Italian Amalfi coast in spring 2004 provided evidence that the myth which since Strabon has been sure on the location (Sirenussae islands) is based on acoustic phenomena on the site. For such a precise location of cultural memory, there must be a foundation in the acoustic real. Sirens are "non-human" in terms of machinic or cyborg sound. What makes the Homeric, mythologic Siren motive relevant for present media archaeology of sound is the intervention of the phonograph, since for the first time, the replay of recorded voices were considered like the presence of humans - as expressed in the chapter "Fülle des Wohlklangs" in Thomas Mann's novel Zauberberg while at the same time knowing it is reproduced from dead signals on a storage medium like phonograph or gramophone - and even more with electronic sound processing. Here, the uncanniness of the monstruous Sirens corresponds with the imaginary of technology itself. Parikka defines "imaginary media as shorthand for what can be addressed as the non-human side of technical media; the fact that technical media are media of non-solid, non-phenomenologial worlds (electro-magnetic fields, highlevel mathematics, speeds beyond human comprehension"15 - which, beyond the phonograph, is true for electronic sound media up to the digital sound processing of today with "ultra-sonic" speed of processing. The zone of indeterminacy between human and non-human sound is what Maurice Blanchot identified as the "acoustemic" core of the Siren songs. Blanchot takes into account the notion of human singing turned upside down: "Some have said that is was an inhuman song - a natural sound (is there such a thing as an unnatural sound?) but on the borderline of nature, at any rate foreign to man; almost inaudible [...]. Others suggested that it [...] simply imitated the song of a normal human being, but since the Sirens, even if they sang like human beings, were only beasts [...], their song was so unearthly that it forced those who heard it to realise the inhumanness of all human singing."16 The undoing of the anthropologically and culturally significant difference between life and death is the sonic, i. e.: epistemic message of the uncanny "Siren" mythologeme (with mythos literally nameing the acoustic rumour). This challenge which returned for the digital culture with the "Turing test" and the cybernetic question addressed to the electronic brain: Can computers think? The other uncanniness derives from the technological sublime: "Kittler mentions the Sirens as one such example of resursive history 'where the same issue is taken up again and again at regular intervals but with different connotations and results' [...]: from seductive Greeek sea nymphs to monsters of early Christianity, from mermaids of the Middle Ages to the nineteenth-century technical use of the term in the form we understand it, i. e. as a signaling device with a sound, subsequently playing a key part in the mapping of the thresholds of hearing as well as the development of radio [...]."17 The artefactual correlate for the Sirens as subject of soundarchaeological research is the technical siren apparatus.18 The experimental settings of the Li Galli expedition has been to fold both meanings of the "siren" upon each other - the cultural and the technological one. That is why it was almost obligatory to emit across the Li Galli island, among other sound sources, acoustic impulses generated by the technical double-siren. When with the technical siren as sonic device (as developed by Cagniard de Latour and refined by Hermann von Helmholtz) the voice (the vocal formants) became mathematically analysable / calculable, this had a retroeffect towards the metaphysics of the voice in occidental ontology: Since then, a human voice is considered and perceived as a frequency-based vibration event in itself, no less "mechanical" than technical machines. An ahistorical short-circuiting of distant times takes place once a sound generator - the technical siren - confronts its mythological object, the Homeric Sirens: "Recursions fold time and thus enable direct contact between points and events (and S/sirens) that are separated when history time is stretched out on a continuous line. In both cases, incidentally, the obvious Deleuzian echoes work"19 "A similar procedure was carried out on a technical level: sound-producing technologies were used to project sounds to and from the islets while being recorded by storage devices. The subsequent (technical) analysis of the (technical) recordings produced an interesting (technical) insight: Sounds emanating from the main island Gallo Lungo hit the Siren rocks Castelluccio and La Rotonda and, much like a ball caught between the flappers of a pinball machine, start to echo between the two, resulting in the disorienting sonic phenomenon experienced by Bradford [...]. The special twist of this forensic Siren story, however, is the fact that one of the sound-producing devices used to disconceal the ancient Sirens was an aerophone, a noisemaker that produces signs by interrupting the air flow—in other words, a modern siren. Sirens track Sirens"20 - which is both acoustic media archaeology and media archaeology of the acoustic. This pre-technological (thus only "medial") awareness also acts in preparation of future sound technologies: "The ancient Greek practice of the vowel alphabet sensitizes the culture of knowledge (. . .) From the point of view of the archaeology of knowledge, this beginning of the technology of vocal culture already contains (. . .) its teleo-archaeological end. The true message of the phonetic alphabet as a cultural technique is the desire to achieve an indexical relationship to the sound of the voice, but this outstrips the capabilities of symbolic notation. The phantasm is only realized by a genuine media technology, the phonograph."21 All of the sudden, comments Winthrop-Young, we are carried into Walter Benjamin's media-theoretical territory, especially into section XIV of his essay on The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Just like Dadaism employed literary and artistic means to achieve effects that now can easily be had in movie theatres, Benjamin noted that every historical era 'shows critical epochs in which a certain art form aspires to effects which could be fully obtained only with a changed technical standard'."22 This happens on the level of the symbolic signifiers as well. The alphabetic vowels transposed Homer's voice into recording, while the technical siren generates tones by numbered holes = numerical frequencies as the reverse of vocal waves. "In the case of the Siren-to-siren shortcut we are leap-frogging across millenia. Here, however, we come across a recursion of Hegelian splendor and magnitude that is related to the re-functionalization of the Greek alphabet. By way of a simple conversion of ordinal into cardinal, alpha, the first letter, also became the number 1, beta, the second letter, also became 2; gamma also became 3, and so on. <...> In the Pythagorean tradition, however, the perfect harmony (expressed mathematically and musically) is that of the two sirens singing."23 --Let me once more reverse the expression "Listening to Modernity": Modern listening is listening with technological ears. The experimental setting of investigating the acoustic properties of the Siren song area at the Amalfi coast is a perfect example of modern listening in its mediaarchaeological sense. "The white noise signal recorded between the two smaller islets showed higher amplitudes in the 1000-5000 Hz frequency range than the same signal recorded just in front of the islands. [...] This result can be seen clearly in the lower harmonics where the main energy of sound is located. The changes in loudness were distinctly perceived even to the naked ear. Our results lead to the conclusion that the specific geographical constellation of the island acts as an acoustic amplifier between La Castellucia and La Rotonda in the direction towards Capri."24 If we suppose that "the Sirens" play more than just a metaphorical role in representing the true, perfect sound that ancient poets desired, "[...] it should be reasonable to find further evidence and to think of investigations that reach beyond traditional philological methods. Sirens like Muses to minds of oral poetry were entities of real experience. They provided wisdom from within and through the audible domain (see ‘Introduction’ above). One the one hand, as our experiments show, there is only a sharp line between real acoustic phenomena and acoustic hallucinations at the Sirens’ Island. On the other hand in early Greek thinking Sirens incorporate acoustical features of superior soundings and of musicological relevance."25 Let us media-archaeologically focus on the acoustic evidence or (in order to avoid oculo-centrism) rather: e-tonality which arises from this archeoacoustic research: "As a matter of fact, [...] intervals given together by two Sirens at Li Galli can only be differentiated as being ‘accords’, that means having two separate sources, if their overtone structures do not merge. This is not the case for octaves, fifths or fourths but at first with the third and further with less ‘consonant’ intervals counting up the overtone series. Since the pure major and minor thirds are typical for enharmonic scales and less ‘consonant’ intervals are not likely to be of great use for any harmonic accompaniment, this finding adds to the evidence that (i) pure thirds are the characteristic intervals of enharmonic tuning in Ancient Greece and (ii) that it has been developed from an early diaphony for which next to the double-aulos the casus dualis in the song of the two sirens holds." "The casus dualis of Homer’s Sirens could also be acoustically motivated leading to a musicological hypothesis of an early Greek diaphony based on enharmony. However the questions who are and what were the sirens cannot be determined by measurement and a more quantitative analysis of musical intervals will require further ‘acoustic reasoning’ at the site."26 II HISTORY OR RESONANCE? THE "SOUND" OF TRADITION A different kind of archive: sonic memory The research into past sonospheres and ways of listening long-time ago has emerged as a new kind of historical knowledge. The economy of knowledge is being enriched by the "sonosphere", or alternativeley: ambient sound. The BBC World Service has launched the "Save our Sounds" project, looking to "archivize" sounds that may soon be lost due to the post-industrical world. But caution, this is not an archive: As long as an algorithm is missing which rules the transition of sound provenience to permanent storage, it is just an ideosyncratic random collection. So far historiography has privileged the visible and readable archival records (thus fulfilling McLuhan's diagnosis of the Gutenberg Galaxy as being dominated by visual knowledge). But since Edison's phonograph sound, noise and voices can be technically recorded and thus memorized. The Phonograph (respectively Emil Berliner's grammophone) registers the whole range of acoustic events. Whereas in the musical notation (developed by the Greeks and Guido of Arezzo in analogy to the alphabet) a symbolic recording takes place, the phonograph registers the physically real frequency. The alphabetic symbolism reduces acoustic events to the "musical" (harmonical order), whereas the register of the real encompasses the sonic (including noise, a-rhythmical temporal phase shifting such as "swing", differing amplitudes and frequencies) - an anarchive of sound (technological storage) as opposed to the archival order of musical notation. As a research method, an archaeology of listening differs from Hearing History27.; it does not simply aim to widen the range of source material for historians. Let us propose something like a "diagrammatic listening", with the diagram having no indexical or iconic relation to a concrete listening into a symbolic, logical, rather than "historical" field. To what degree is listening dependent on sound as event in matter? In the symbolic order (score notation), "structural listening can take place in the mind through intelligent score-reading, without the physical presence of an external sound source."28 As once conceived by Theodor W. Adorno, "the silent, imaginative reading of music could render actual playing as superfluous as speaking is made by reading of written material"29. With the phonograph, hearing become attentive of all kinds of sounds, regardless of their source and quality, just like the inner ear transduces vibrations analogue to electro-mechanical sound reproduction.30 With phonographic recording, listening became ahistorical, subject to the timeinvariant reproducibility of signals. The phonograph separated sound production from its historical index which is (in terms of Walter Benjamin) unique, "auratic" place and time. The Greek term mousiké encompassed not only musical articulation in the narrow sense, but dance and poetry as well. The essential operation to create an archive of such moving ("time-based") arts, of course, is recording: either symbolically (by dance notation in the tradition of writing / graphé), or by media endowed with the capacity to register the physically real audiovisual signals. Media-active archaeology can be applied to past sound, generating a different kind of audio-archive. The micro-physical close reading of sound, where the materiality of the recording medium itself becomes poetical, dissolves any semantically meaningful archival unit into discrete blocks of signals. Instead of musicological hermeneutics, the media-archaeological gaze is required here (very materially). The media archaeologist, with all his "passion of distance" (Friedrich Nietzsche), does not hallucinate life when he listens to recorded voices; the media archaeological exercise is to be aware at each given moment that we are dealing with technical media, not humans, that we are not speaking with the dead but dead media operate. While the recorded signal principally stays invariant over time, the body from which the song originated apparently has aged, thus being subject to historical time. Sound recording does not simply unfold as evolutionary course of technology in history, but the phonographic record on the one hand, the magnetic record on tape on the other, and finally the digital recording represent fundamentally different materialities and logics (techo/logies) in terms of their ways of registering time-variant signals, time-based forms of reproduction and their "archival" being in time. The electronic tube, especially the triode, once liberated technical media from mechanical constrains, thus: from erasure over time; still the tube or transistor are subject to decay over time themselves. Negentropic persistence against entropic time31 ows its ahistoricity rather to its different form of registering: not by signals (recording the physically real acoustic event), but by symbols. Let me - in according with Günther Stern's unfinished habilitation Die musikalische Situation (ca. 1930) - fundamentally question the historicity insist that in many respects sound – heard, recorded or transmitted – is radically ahistorical; its specificity could not be captured and subsumed by the logocentrism of traditional narrative historiography. Serious engagement with “the sonic” – sound as sound and sound as time – could open up access to a plurality of non-narrative temporalities, beyond history-writing’s reliance on Gutenberg-era structures of printed language and narrative contextualization. Historians among us will probably responded with reservations on this point, stressing the cultural context of sound’s perception, production and consumption, and suggest that sound history, as any other, should guard against the persistent chimera of unmediated access to the past. Is there a "sound of the archive"? Different from the archive as symbolic order composed of records in alphabetic, that is: discrete notation, there is an para-archival modality of sub-textual, signal-based recording of the past: the sound of times past. The traditional sonic experience in real archives is silence; historical imagination (as expressed by the Romantic French historian Jules Michelet32) though hallucinates the voices of the dead here. The mediaarchaeological ear, on the contrary, is trained to actually stand archival silence, gaps, voids. But silence itself can become part of the archive. The software for sound analysis Audacity actually provides an algorithm called "Silence Finder". The sheer endurance of matter is a Bergsonean time which passes. While an empty space within a painting positively endures with time, silence in acoustics is always a temporal (though negative) event itself. Historians among us will always remind us that there is no unmediated access to the past. But in the negative sound of the archive, its silence, we listen to the past in its truest articulation. Let us pay respect to absence instead of converting it into the specters of a false memory. When an ancient "Datassette" is being loaded from external tape memory into the ROM of a Commodore 64 computer, we are actually listening to data music. What we hear is not sound as memory content like an old persussionassisted song33, but rather the sound of computer rmemory itself, that is: a software program which is "scipture" (though in the alphanumeric mode). We are listening to the data archive which is not sonic memory but sonicity. The (A)Historicity of Musical Articulation and Listening The attention to silence as the "sound of the archive" leads us to discuss the relation of time, historicity and sound in a more fundamental sense. Since the emergence of acoustics, declared once by Archytas of Taras in South Italy in the name of aisthesis (which is physiological, not cognitive perception), the physical science of sound and the cultural notion of harmonic relations drifted apart. It was Hermann von Helmholtz who insisted on their interlacing; in the world of harmonic scales, both natural laws and cultural historicism converge.34 Alexander Rehding points out that Hugo Riemann wanted to take his share in the prestige of natural sciences35, in search of the (scientifically impossible) undertone. What does this indicate? It shares with the (natural) sciences the assumption of a-historical, time-invariant laws, in an effort to translate this into aesthetic experience. A similar Kantean Widerstreit between natural-physical a-temporality and the irreducible cultural historical indexicality takes place with technological media like sound recording. Musical listening especially merges both areas. Musical listening, for Hugo Riemann, is "logical activity"36, a primarily mental process, thus a rather cognitive impression of tones, different from the merely physiological sensation of sound as physical event.37 Every cultural entity has, according to Wilhelm Dilthey, a horizon of understanding (Verstehenshorizont). This leads to the familiar hermeneutic circle: "We reconstruct the historicity of a piece of music by reconstructing the time horizon of its epoch. Thus, we write general history and treat music as an element of that general history. Here applies our argument: <...> The predominant manifestation of this spirit is the musical work itself, or to be more precise: the event of the musical work. There is no other relevant time structure for understanding a piece of music than the time structure of the music itself. The historicity of music is enclosed in the music itself."38 This eigenzeit emanzipates from the standard theory of historicism. "Music creates its own history which has nothing to do with Dilthey's and Ranke's concepts of an 'Universalgeschichte'. Nevertheless, we do not believe that music history according to this standard theory is redundant. Classical historical knowledge of music has its legitimation when the question is how music is embedded in broader cultural textures. But if we ask for the genuine history of music, classical historiography can only be the first step. The second has to be a reconstruction of the specific time structures unfolded by the piece of music itself. These temporal relations cease to be historiographically linear ones." To what degree does the historicity of sound depend on its material embodiment? "Is the sound of an existing Roman era bell dating from the third century a more ancient sound? For this to be the case we would have to think of the bell itself as an encoding of some 'sound'; that sound, in turn, would have to include the splashing of the molten brass, the beating by smiths' hammers etc. But the sound the bell produces in its current use is far from being a recording of these sounds." [<...> I do not consider the hypothetical bell itself to be either the substance or the carrier of a more ancient sound."]39 Phonographic "engraving" in fact is sound in latency. What is the VollzugSetzung"), that is: to become medium (the Heideggerean "beeing-intime")? This can be correlated with micro-temporal "musical" experience (which itself corresponds with micro-temporal actions within technologies). In fact, the Heideggerean "beeing-to-death" which is the temporal experience of human existence structurally (not explicitely) corresponds with musical listening when a melody is mentally experienced as a unity even if acoustically it consists of a discontinuous or fragmentary series of single tones - a phenomenon both mentioned by Henri Bergson's philosophy of temporal duration (as opposed to mathematized time of clocking) and by Edmund Husserls as example of "innere Zeiterfahrung" (the Augustinean experience of subjective time). It is the "finality phenomenon"40 which determines the aesthetic experience of a melody. "After such a definition, how shall one speak of Wagner's 'endless melodies'?"41 All of the sudden, the conflict between the physically impossible ideal sinus wave in Fourier Analysis and its transient momentum as an actually physically performed tone epistemologically resonates. Modernist spatio-tempor(e)alty: "acoustic space" As a new branch of memory studies the research into past sonospheres (from long time ago) has emerged. "Sonic environment" is commonly associated with industrial and other sources of noise.42 Let me fundamentally argue for an archaeology complementary to the social history of such sonospheres, in the epistemological sense attributed to sonic expression by Marshall McLuhan. Technical sound is not just mechanical violence to the ear or aesthetic pleasure for the brain (von Helmholtz) but adressing the human (pseudo-)sense of temporality. The "tuning of the world" (Schafer 1977) is a timing of the world as well. What looks physical (acoustic) is temporal in its subliminal affect. If the "sonic environment" is extended to so-called Hertzean waves as well, electromagnetism turns out sublime in all ways. The specificity of such sonic articulation can not be captured and subsumed by the logocentrism of traditional narrative historiography. "Acoustic space", as emphasised by Marshall McLuhan, is of a different temporal nature: not linear, but synchronous, simultaneously from every direction at once.43 McLuhan once called it "echo land". Let us take this metaphor literally: acoustic echo implies delay, the very temporality induced by the medium as channel of signal transfer which once led Aristotle in his treatise Peri psyches to deal (media-)philosophically with the "Inbetween" (to metaxy) - no neo-logism as a term by Aristotle, rather a graphical neo-graphism by writing the adverb with a capital letter, thus turning it into a noun which (after its translation by medieval scholars) turned into the well-known medium. Serious engagement with “the sonic” – sound as sound and sound as time – could open up access to a plurality of non-narrative temporalities, beyond history-writing’s reliance on Gutenberg-era structures of printed language and narrative contextualization. --In accordance with McLuhan, Walter J. Ong emphasized: "Vision comes to a human being from one direction at a time"44 - die perspektivische Ausrichtung, der Fluchtpunkt (der im Zeitfeld die Konzentration auf den Zeitpunkt privilegiert). "When I hear <...> I gather sound simultaneously from every direction at once: I am at the center of my auditory world <...>. You can immerse yourself in hearing, in sound."45 "PHOTOGRAPHY was the mechanization of the perspective painting and of the arrested eye"; "Telephone, gramophone, and RADIO are the mechanization of post-literate acoustic space"; "We are back in acoustic space".46 Such sonic space is understood here as the epistemological existence of sound. Notwithstanding his confusing electricity and electronics, McLuhan made a crucial discovery about the intrinsically "acoustic" structure of electronic mediascapes. In a letter to P. F. Strawson, author of Individuals. An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics (1959), McLuhan quotes from that work: "Sounds, of course, have temporal relations to each other ... but they have no intrinsic spatial characters."47 The immediacy of electricity has been valued essential by McLuhan as the definite difference to the Gutenberg world of scriptural and printed information: "Visual man is the most extreme case of abstractionism because has has separated his visual faculty from the other senses <...>. <...> today it is threatened, not by anly single factors such as television or radio, but by the electric speed of information movement in general. Electric speed is approximately the speed of light, and this consitutes an information environment that has basically an acoustic structure."48 Very media-archaeologically, McLuhan's term "acoustic structure" evidently refers to an epistemological ground, not to the acoustic figure (what ears can hear). This ground-breaking took place with the collapse of Euclidic space into Riemann spaces and culminates around 1900 with quantum physical notions (the para-sonic wave/particle dualism, up to the "superstring" theory of today) on the one side, and Henri Bergson's dynamic idea of matter as image in the sense of vibrating waves and frequencies.49 McLuhan's "acoustic space" is oscillating time and implicitely re-turns in Gilles Deleuze's "interval" philosophy. In an epistemological sense, the sonic is not about (or limited to) the audible at all, but a mode of revealing modalities of temporal processuality. At the speed of light, information is simultaneous from all directions and this is the structure of the act of hearing, i. e. the message or effect of electric information is acoustic - even when it is perceived as an electronic image (as defined by the video artist Bill Viola in his essay "The Sound of One Line Scanning"50). Enrico Caruso's voice: Remembering past sonospheres by technical media Until technical recording of acoustic signals, historiography as well as musicology have privileged the visible and readable archival records alphabetic letters and symbolic musical scores. But since Edison's phonograph, sound, noise and voices can be technically recorded and thus memorized. The Phonograph (respectively Emil Berliner's gramophone) registers a whole range of acoustic events. Whereas in discrete musical notation (in analogy to the alphabet) a symbolic registering of music takes place, the phonograph records the physically real signal. The alphabetic symbolism reduces acoustic events to the "musical" (harmonical order), whereas the register of the real encompasses the sonic (including noise, a-rhythmical temporal phase shifting such as "swing"), generating an anarchive of sound in technological storage) as opposed to the archival order of musical notation. The presence-generating power of technically recorded voices differs fundamentally from the grama-phonic notation of speech in the vocal alphabet. "In <...> sound recording the men and women of the past are present. Marcel Proust makes me think of bygone times. When I hear Kirsten Flagstad as Isolde, with the Royal Opera House Orchestra under the leadership of Sir Thomas Beecham, the voice of the opera legend is concretely present to my ears. The intellect tells me that the recording is 72 years old and stems from Covent Garden, but for my senses, she is with me in space, here and now."51 But different from archivist driven by historical imagination, the media archaeologist, without passion, does not hallucinate life when he listens to recorded voices; his exercise is to be aware at each given moment that we are dealing with media, not humans, that we are not speaking with the dead but media operate in an undeadly mode. Once in operation, media are always undead. Edison cyliders need archival protection, for sure. But once Caruso's voice is articulated by re-playing its recording on Edison cylinder, human percpetion forgets about the archive. Historians among us will probably responded with reservations on this point, stressing that there is no unmediated access to the past. But let us not forget: Technologies of memory, addressing our perception on the affective rather than cognitive level, successfully dissimulate the archive. In order to convince the audience of the sonic fidelity of phonographic recording, the Edison Company in 1916 arranged for an experimental setting in the New York Carnegie Hall: "Alone on the vast stage there stood a mahagony phonograph <...>. In the midst of the hushed silence a white-gloved man emerged from the mysterious region behind the draperies, solemnly placed a record in the gaping mouth of the machine, wound it up and vanished. Then Mme. Rappold stepped forward, and leaning one arm affectionately on the phonograph began to sing an air from "Tosca." The phonograph also began to sing "Vissi d' Arte, Vissi d'Amore" at the top of its mechanical lungs, with exactly the same accent and intonation, even stopping to take a breath in unison with the prima donna. Occasionally the singer would stop and the phonograph carried on the air alone. When the mechanical voice ended Mme. Rappold sang. The fascination for the audience lay in guessing whether Mme. Rappold or the phonograph was at work, or whether they were singing together."52 A similar staging of human vocal performance versus apparative acoustic operativity has been commented by the Boston Journal in the same year: „It was actually impossible to distinguish the singer‘s living voice from its re-creation in the instrument.“53 What took place is the chrono-Sirenism present“ (Peter Wicke), induced by technical recording. From the first sound recording onwards humans (like the dog Nipper on the notorious gramophone record label "His Master's Voice") can listen to the voice of the dead. My thesis is that this has since been a choque to the logocentristic occidental culture, since logocenstrism is no metaphysics any more has become actual physical signal recording. This technologically induced trauma has not been epistemologically digested yet. To illustrate this, let us listens to a Caruso recording: "Starting in 1902, Enrico Caruso made a large number of disc phonograph recordings most of which have been re-engineered and released over the last century. It is one the most persistent (and lucrative) instances of sonic remediation, as Caruso's voice migrated from shellac to vinyl to CDs and i-pods, while all around his voice orchestral accompaniments were enhanced, removed and overdubbed. [...] The posthumous career of Caruso is a sequence of archival transformations. All media technologies are 'archives of cultural engineering', and in ways which give a lot of additional meaning to to McLuhan's mantra that the content of one medium is always another another medium, each archive recursively processes another."54 "These recursive remediations are not only aesthetic and commercial undertakings, they are also archaeological endevavours. If, for instance, the inscribed phonographic traces on wax cylinders from Edison's days are opto-digitally retraced, inaccessible sound recording become audible again. 'Frozen voices, confined to analogue and long-forgotten storage media, wait for their (digital) unfreezing' (248). Media are the new capital-s subjects of media archaeology; [we, the former subjects, can sit back and enjoy the 'blessing of the media-archaeological gaze' (249)]."55 If for this reanimation of dead sounds and images I dare to use the word "redemption", this is not simply a reference to Walter Benjamin's "messianic" historical materialism; we might phrase it rather the other way round: Benjamin's awkward phrasing is now itself redeemed by technical media. Message or noise? Acoustic archaeology To perform a psycho-acoustic experiment of a very simple kind, let us imagine an ancient phonographic recording of a song or voice. Whatever the timbre might seem one will acoustically hallucinate as well the scratching, the noise of the recording apparatus. True media archaeology starts here: The phonograph as media artefact does not only preserve the memory of cultural semantics but past technical knowledge as well, a kind of frozen media knowldege embodied in engineering and waiting to be unrevealed by media-archaeological consciousness. What does "Listening to Technology"56 mean? Let us emphasize this in favor of close listening: The Museum of Endangered Sounds takes care of the sound of "dead media".57 The Technical Committee of IASA in its recommendations from December 2005 insists that the originally intended signal is just one part of an archival audio record; accidental artefacts like noise and distortion are part of it as well - be it because of faults in the recording process itself or as a result of later damage caused in transmission. Both kind of signals, the semantic and the «mémoire involontaire», message and noise, need to be preserved in media-archival conservation ethics. Edison wax cylinders from the beginning of the 20th century may very well contain background recordings of environments that were never entended for memory but now "recall (if an earlier event can recall a later one) the Soundscape Project in Vancouver [...]"58. What once has been considered as undesirable noises may from a different perspective (or better: hearing) turns out as a kind of acoustic cinema. This leads to the counterhistorical idea of simultaneity, «the co-existence of two different times, (or three if you take into account the now-time you are listening in, which is always changing)» (Moore / Kiefer). It is the mediaarchaeological intention to dig into collections of early recording machines in such a non-historical way (anti-hermeneutically). Out of this archaeological site develops a different "hearing" of modern history, a notion of the sound of the past based on waves, simultaneous time and shifting soundscapes.59 Let us differentiate between the cultural „social“ respectively „collective“ (Halbwachs) memory of sonic events (auditory memory) and the actual (media) recording of sonic articulation from the past. For an archaeology of the acoustic in cultural memory the human auditory sense does not suffice. Let us, therefore, track the sonic trace with genuine tools of media studies (which is technical media). One way of „acoustic archaeology“ is to play a musical partition on historic instruments. But the real archaeologists in media archaeology are the media themselves not mass media (the media of representation), but measuring media which are able to de-cipher physically real signals techno-analogically, and representing them in graphic forms alternative to alphabetic writing, requiring „moving“ diagrams (sine sound is articulation in time): the oscilloscope. Material entropy versus symbolic endurance of sound recording With the refinement of the Phenician alphabet to the Greek phonetic alphabet (Ong actually calls it "technologizing of the word"60), acoustic articulation (speech, singing, oral poetry) became symbolically recordable for real re-play. In a surprinsingly optimistic way, the composer Béla Bartók once commented the memory conditions in the age of reproducable media recordings, in this case: the phonographic recordings of oral poetry made by Milman Parry which he personally transcribed from signal recording to symbolic musical score: "The records are mechanically fairly good <...> . Aluminum disks were used; this material is very durable so that one may play back the records heaven knows how often, without the slightest deterioration. Sometimes the tracks are too shallow, but copies can be made in almost limitless numbers." But the physical reality of such storage devices over time is the evidence that they are increasingly subject to macro-temporal entropy such as the material deteriorisation of Edison cylinders or magnetic tapes. Symbolic notation (muscial scores end in paper archives) differ from signal recording (which rather result in media collections): "Notation wants music to be forgotten, in order to fix it and to cast it into identical reproduction, namely the objectivation of the gesture, which for all music of barbarian cultures martyrs the eardrum of the listener. The eternization of music through notation contains a deadly moment: what it captures becomes irrevocable ... Musical notation <...> is about eternity: it kills music as a natural phenomenon in order to conserve it — once it is broken — as a spiritual entity: The survival of music in its persistence presupposes the killing of its here and now, and achieves within the notation the ban from its mimetic representation."61 Digitized signals at first sight resemble the tradition of music notation (the score), but are endowed with operational activity; they are algorithmically executable. Symbolic archival permanence is almost timeinvariant, sublated from change with time, leading to ahistorical immediacy in the moment of re-play. In May 2011 two Black Boxes could finally be rescued from the ground of the Atlantic sea two years after the Air France aeroplane crash: the data recorder and the voice recorder keeping the last words of the pilots in the cockpit but as well the background noises which retrospectively signal the unfolding desaster. The recordings proved to be miraculously intact. Both data recorders consist of memory chips which keep their magnetic charge, different from mechanically vulnerable previous recording media. Whereas mechanical records still represent the culturally familiar form of physical impression (writing), electro-magnetic latency is a different, sublime, uncanny form of insivible, non-haptic memory. The voices and sounds emanating from such a black box are radically bodyless, being in a different time than the familiar historio-graphical time. With a micro-physical close reading (or rather listening as „understanding“) of sound, the materiality of the recording medium itself becomes poetical. Instead of musicological hermeneutics, the mediaarchaeological gaze (or rather: ear) is required here, very materially. Sonic memory's two technological embodiments: physical signal and archival symbol Archival endurance (oscillating between historical and entropical time) is undermined when a record is not fixed any more on a permanent storage medium but takes places electronically; flow (the current) replaces the inscription. The difference between mechanical and electro-magnetic audio recording is not just a technical, but as well an epistemological one. While the phonograph belongs to what Jules-Étienne Marey once called the „graphical method“ (analog registering of signals by curves), the magnetophone is based upon the electro-magnetic field which represents a completely different type of recording, in fact a true „medium“. What used to be invasive writing has been substituted by electronic recording; writing now re-turns as digital encoding in different qualities. The video artist Bill Viola in his essay on the sound of electronic images pointed out "the current shift from analogue's sequential waves to digital's recombinant codes" in technology.62 Sampling and quantizing of acoustic signals analytically transforms the time signal into the information of frequencies which is the condition for technical resynthesis (Fourier transformation). Digitalization means a radical transformation in the ontology of the sound record - from the physical signal to a matrix (chart, list) of its numerical values. Media culture turns from phonocentrism to mathematics. The Technical Committee of the International Association of Sound Archives in her standard recommendations from December 2005 points out that any such rules need to be revised when technological changes of conditions (the media-economic dispositive) takes place.63 Digital data need constant up-dating (in terms of software) and „migration“ (in terms of hardware to embody them). From that derives a change from the ideal of archival eternity to permanent change - the dynarchive. When the transfer techniques of audio carriers changes from technically extended writing such as analog phonography to calculation (digization), this is not just another version of the materialities of tradition, but a conceptual change. From that moment on, material tradition is not just function of a linear time base any more (the speed of history), but a new, basically atemporal dimension (acceleration), short-cutting the emphatic time arrow and demanding for a partial differentiation (just like the infinitesimal calculus was introduced by Leibniz as a measure of nonlinear change within speed). III SOUND TECHNICALLY RESCUED FROM THE ARCHIVE Active media archaeology: Sonic revelation (articulation) from the past (Au Claire de Lune) Media archaeology is concerned with latent, implicit rather than manifest, directly audible sound knowledge within the material dispositive - which is not explicitely turned into written knowledge yet. In a similar sense, since Pre-Socratic Greek philosophy, music has not just been a practice of acoustic pleasure and entertainment, but served as a model of knowledge - mousiké epistéme. More specifically, in the absence of signal processing media, musical analysis served as a substitute for insight into time-based processes. As such the science of music both enhanced and hindered the insight into acoustic media, as in the case of Galileo Galilei. With his experiments of generating sound by rubbing patterned surfaces, Galileo involuntarily came close to inventing the phonograph.64 But instead of crossing that border, as the son of the theoretician of music Vincenzo Galilei he remained imprisoned in Pythagorean ideology. In sonic articulations he detected primarily music, not "audio": the proof of the connection between numerical proportionality in tonal pitch and the impulse theory of sound. Let us put a special emphasis on “sound” memory / storage / transmission, since this has been the most “immaterial” cultural articulation (before the electronic age) already. History as academic discipline is a primarily text-based science, as opposed to a science of signals which has opened a new field of research not just as an additional source for historical inquiry; with photography, the phonograph and with cinematography an alternative field of agenda has been set. So-called Humanities (as defined by Wilhelm Dilthey) has for the longest time not been concerned with the phyically real - due to the limits of hermeneutics as text-oriented method, to the privigeging of narrative as dominant form of representation and because of an essential lack of nonsymbolic recording media of the real. Battles have been described and interpreted, but the real noise and smell of a combat could not be transmitted until the arrival of the Edison phonograph.65 Phonography did not just provide historical research with a new kind of source material; it rather articulated new, rather a-historical forms of tempor(e)ality on the level of the physically and mathematically real (techno/logy). Archaeo-acoustics deals with "modern", that is: technological hearing in the sense that it is the sonic media (as active "archaeologists") which reveal these previous sounds of the past. In one of his media artistic projects, the sound archaeologist Paul deMarinis translates "illustrations and engravings <!> of sound vibrations from old physics and acoustics texts, many of them predating the invention of the phonograph"66, back into sound files. DeMarinis finally adds a "technical note": "The traces were scanned on a flatbed scanner, extracted and isolated by a number of processes in Photoshop, then transformed into audio files via a custom patcher in Max/MSP. The sounds were then presented <...> as aiff files played back on a conventional CD player" <252>. Let us get tuned to this non-canonical epistemology, not by texts and the spoken word, but by a French childrens‘ song: Au Claire de Lune. In an act of active media archaeology by the computer itself it has been achieved that the graphic recording of Léon Scott‘s analyses of the human voice could be re-transformed into acoustic articulation: By means of optical reading of signals and application of digital filters, it is possible to digitally trace past acoustic signals from records. From such an operation we expect sound, but really what we primarily hear is noise - just like the first (archived) recording of sound in Norway, a tinfoil flattened to a „document“ and annotated by a remark by a former collector who claims this has been the first Norwegian recording of music on Edison cylinder. The digital reading, algorithmic filtering and final re-sonification of this record by a laboratory in Southampton led to a kind of re-sonification where the ear wants to detect something like music or speech - but it actually hears nothing but noisy patterns. Past sound is not just "restored" by applying digital filters but has to be remembered with all the traces of decay which has been part of its tradition, its media-temporal (entropic) characteristics must be archivized as well: the scratches, the noise of an ancient phonographic cylinder when being digitized. Let us remain close to the physical record. If past information is not just symbolically emulated but simulated, its temporal (entropic) behavior must be archivized as well - like the scratch, the noise of an ancient Edison phonographic cylinder when being digitized. One method of keeping recorded sound from the past alive is known from computing as physical modelling (f. e. in sound reproduction); f. e. the chemical decay of recordings from the past such as Edison cylinders belongs to the essential feature of the sonic record and can now be algorithmically simulated. Not just the recorded sound is emulated, but the chemical process within the sound carrier itself. A "close reading" of a physical record like a magnetic tape is a laser scan of its magnetic field (which can be made visible by chemical colouring) which than can be digitally processed into sound again. When sound, let to its own surroundings, articulates it-self, it is rather noise such as can be expected in any transmission channel according to the theory of communication developed by Claude Shannons - a theorem which can be extended to transmission in time as well, that is: tradition. In such noise articulates itself what baroque allegories showed as the nagging „tooth of time“ - the articulation of physical entropy, the manifestation of the temporal arrow; according to the Second Law of Zweiten Thermodynamics each system tends, over time, to increasing dis-order. Against this noise of the real culture (especially techno-logical, that is: „digital“ culture) poses a negentropic insistance, a negation of decay and passing (away). Digital copies of digital records can indeed be produced almost without loss of data (except the quantization noise). Music on Compact Disc or a digitale video can be reproduced frequently with stable quality which was utopean in recent times of analoge recording on magnetic tape. The secret of this temporal unvulnerability is that it is just (physical representations of) numbers which are written on the Compact Disc; even after a thousand copies thus a zero stays zero and one remains one.67 The media-archaeological dispostive for this type of (almost) lossless reproduction of information by identical symbols has been the Gutenberg printing technology (as opposed to handwritten copies of manuscripts) with its negative types to re-produce letters positively in identical numbers a form of reproduction later re-ivented by the photographic negative, the Talbot Kalotype (as different from the unique Daguerre positive), which led Walter Benjamin to remark that reproduction technology both disconnected and freed (“er/löst“) the reproduced object from the realm of tradition, by replacing the unique event (the condition for its „auratic“ character) by its mass multiplicity. Temporal tradition is thus replaced by a rather topological dissemination.68 The tempor(e)ality of „history“ corresponds with the entropic deterioriation of the electric charge and chemical carrier of the magnetic tape versus symbolical, i. e. Almost time-invariant „tradition“. Whereas an analog sound carrier, which is in-formed physical materiality, can still be identified according to the criteria of the historical method, digital signal transfer primarily is information in its communication engineering sense (given by Shannon), that is: unbound from energy and matter by coding (as Norbert Wiener in his Cybernetics insists). The media-historiographically canonized „first“ technical, not just symbolical recording of a human voice (the children song „Mary had a little lamb“) resulted from the experiment of Thomas Alva Edison with the tinfoil phonograph in 1877; this primary scence has been re-enacted by the elderly inventor (Edison) himself: While the recorded signal principally stays invariant over time, the body from which the song originated apparently has aged, being strictly subjected to what we call historical time. But the really first recording of sound (in the media-archaeological sense) has been preserved as relic (in Droysen‘s sense „Überrest“), which is as un-intentional tradition (a Proustean mémoire involontaire, a Bergsonean „counter-archive“ as defined by Paula Amad) originating from Léon-Scott‘s „Phonautograph“ on a turning cylinder (the Kymograph as universal epistemological recording medium of 19th century), once invented not for purpose of replay or for transmission posterity, but just for immediate phonetic analysis (techno-linguistics). In media-active archaeology, the technological apparatus itself turns out to be the archaologist proper. Patrick Feaster and David Giovannoni thus succeeded in re-sonifying the preserved phonautographic engravings (“Schallbilder“), beginning with Scott‘s recording of a sound folk tone of 435 Hz in the year 1859. 150 years later science realized that with optical „reading“ of such acoustic signal lines sound can be resynthesized, and all of the sudden a children‘s song sounds again. What metaphorically looks like the pick-up of sound images by a „virtual, digital gramophone needle“69, in fact is something media-epistemologically different, a picking-up of a completely new kind: digital sampling. Audio-recordings: Listening to the archive in media-archaeological ways The dis-covery of the temporal implications (rather than archaeologically metaphorical "layers") of the archive is not just an operation of the mind or the eyes, but of hearing and literally archival "understanding" as well (German verstehen refers to auditory as well as to cognitive perception). The spatial, text-based archive is familiar as a radically silent place (radical in the sense of the inscription heading the entrance of the Vatican Archives in Rome). Acoustically, this silence might be reinterpreted as an enduring negation of time-based sound, as performed in John Cage's piece 4'33.70 Whereas the scripture-based classical archive is a static array of records on the grand scale and letters on the microscale, which could be brought in motion only by the act of human reading line by line, the Edison phonograph at first glance looks like the first form of "archive in motion", since its recording (notably the early ethnographic field recordings around 1900, leading to the Vienna Phonograph Archive and the Berlin Phonogramm Archive) is based on a continuously rotating, technically moving apparatus both in recording and in re-play (different from cinematographical recording and projection of visual momevent which is based in discrete, mechanically interrupted frames). When we listen to an ancient phonographic record, the audible past (alluding to Jonathan Sterne's book title) very often refers rather to the noise of the recording device (the ancient wax cylinder) than the recorded voice or music. Here, the medium talks both on the level of enunciation and of reference. What do we hear most: the cultural content (the formerly recorded songs) or the medium massage such as limitations in vocal bandwith, even noise (the wax cylinder scratch and groove)? With digital sampling and processing of audio-signals, analog noise is usually significantly filtered, thus: silenced. But the former noise is being replaced by an even more endangering challenge: the "quantizing noise" on the very bit-critical (technical) level of signal sampling, and the migration problems of digital media data and the physical vulnerability of electronic storage media in terms of institutional (cultural) sound tradition. This is not just a technical question, it has an epistemological dimension as well.