Ewing - Amherst College

advertisement

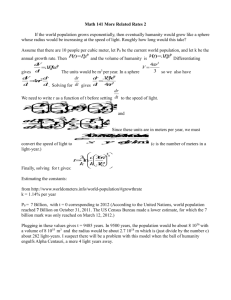

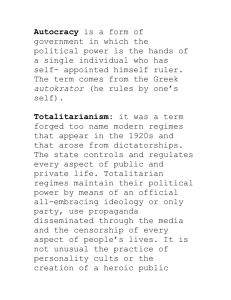

Lindsay Ewing Writing Assignment 01 Defining Nature and Refocusing the Efforts of Conservation Due to the lack of numerous artificial edifices, the simplicity of a wild scene at first glance is immense. Yet as one spends more time observing, the minute details of every blade of grass, the texture of every leaf, and the curvatures of each individual tree branch are incredibly intricate. Lines and shapes and colors converge and diverge. The senses are on overload. There is both silence and noise—so much that one’s head is ready to burst. To tune into one specific aspect of the scene is both necessary and impossible, because there is too much continually changing sensory information to fully comprehend. Thus (supposedly) is nature, designed to evoke sublimity due to (as Burke1 would say) its vastness, light, and infinite complexity. But what is nature? Everything is nature. Everything is natural. In this scene, in the state of Massachusetts, on the Amherst College campus, on the cross country running trail, sunlight illuminates select pieces of grass and trees sway almost imperceptibly as a light breeze whispers through the fields. Crickets roar, the birds squawk, and the clouds move ever so slightly, puffs of cotton candy just out of reach. This is nature. Simultaneously, one observes a discarded pencil lying in the grass, one’s sneakers as she sits and balances a notebook on her lap to draw, and the power structures cutting a jagged line through the organic shapes of trees and greenery. While these “artificial” objects may intrude upon a viewer’s subliminal experience, as they provide stark reminders of the industrialism of human society, they, too, are natural. The Merriam Webster Dictionary2 offers multiple definitions for the term “natural,” most appropriate of which is: “the external world in its entirety.” To envelop the entire external world under the umbrella of nature is sensible, given that religion aside, humanity has no more than 1. 2. Edmund Burke, from “A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful” (1757) “Natural,” Merriam Webster Online Dictionary, accessed September 22, 2011, http://www.merriam-webster.com/ Ewing 2 theories as to why the world exists, why it exists, and why plants, animals, and all other matter came to be. Thus, then, it would be logical to say that humanity and its creations are just as natural as ants and their creations of ant hills of dirt—even the synthetic materials of humanity are actually then “natural.” This is not to say all synthetics and man-made items are healthy and pleasing from the standpoint of sublimity; rather, that the term “nature” is often misinterpreted. It is a common misconception of humanity to think of nature as places that have not been altered by its race. Given the atmospheric changes humanity has caused, it is firstly erroneous to think that any place in the world is still “natural” by the standards of the aforementioned definition (as all have been touched at least indirectly). Secondly, it is illogical to think that many of the places that are considered natural (such as the national parks) have not been touched by humans directly in addition to indirectly: countless monetary resources are directed towards the manicuring such places every year—mowing lawns, removing fallen trees, etc. If something exists, it is natural. Therefore the transformation of the face of the planet from “things that grow” to “things that humans built” must be necessitated by some scientific plan or a higher power of some sort. The true question then, as humanity looks towards the conservation of areas it considers sublime and “natural” as per the misconstrued definition as places “untouched” by humans, is what parts of nature (the whole world) does it want to save and why? Are the landscapes of the Amherst cross country trail and the national parks more sublime than the skyscrapers in New York City because we have been trained to think so, or because they actually trigger something in the human brain that is healthy and pleasurable? Regardless, humanity must stop “kidding itself” that its iconic waterfalls and forests are impressive because they were not built out of metal. Thus, the issue in society is not that we are losing nature; it is that the face of the planet is changing and we refuse to attempt to appreciate it. Ewing 3