the case of potato supply chain in the Upper Rift Valley

advertisement

Analysis of the causes of low adoption in less developed agrifood chains: the

case of potato supply chain in the Upper Rift Valley region of Ethiopia

Gumataw K. Abebe1, 2, Jos Bijman1, Stefano Pascucci1, Onno Omta1, Admasu Tsegaye3

1

Wageningen University, Management Studies Group, Hollandseweg 1, 6706 KN Wageningen, The

Netherlands, gumataw.abebe@wur.nl; 2 Hawassa University; 3Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia.

Abstract

The main purpose of study was to analyse the causes of low adoption for the released potato

varieties (RVs) by the ware potato growers in the Upper Rift Valley Region of Ethiopia. The

study systematically analyzed the main production and market-related quality characteristics

of both the RVs and the local varieties (LVs), and how information on product quality is

exchanged and controlled in the chain. To achieve this objective, data were collected from a

total of 460 ware potato growers (346 in the first round and 114 in the second round) and 34

downstream actors. The result shows that while the RVs are preferred for their productionrelated characteristics, the LVs are more preferred for their market-related characteristics. In

this situation, growers opt to grow the dominant LVs in order to align (match) their

production decision with the quality requirements of downstream actors. This result

contributes to the existing theory of technology adoption, which has largely focused on

individual characteristics, that market conditions are important factors in improving the

likelihood of technology adoption. The implication for research/policy is that there is need to

change the existing top-down system of technology adoption to include the local knowledge

into the breeding programs of research institutions.

Key words: quality, alignment, local knowledge, adoption, Ethiopia, potato, supply chain

1. Introduction

In an effort to improve the performance of the potato sector, the Ethiopian Institute of

Agricultural Research (EIAR) introduced around 18 improved potato varieties in the last two

decades. However, the rate of adoption1 for those released varieties by ware potato growers

was very low compared to the so called “local2” varieties. Data from a national representative

survey of over 8000 households revealed that the use of improved potato seed varieties in

Ethiopia is about 0.5% (ESCS 2005). The problem of low adoption is not only limited to

potato, it also extends to other crops in Ethiopia (McGuire, 2005; Byerlee et al., 2007; Abate

et al., 2011). For example, in the 2005 crop season, 98% of all the seeds used for planting

were local seeds carried over from the previous harvest.

However, the existing low utilization of improved potato varieties has to be changed for a

number of reasons. First, potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is a rapidly expanding crop in

Ethiopia (Mulatu et al., 2005) with the potential to grow in the 70% (10M ha) of the arable

land (FAO 2008). Second, since the Ethiopian government considers potato as a strategic

crop, a lot of public money is being spent on potato research. Third, it has increasingly

become an important source of cash for farmers (Gildemacher et al., 2009). Fourth, potato

yields high productivity per unit of area and time; and hence is one of the key crops for food

1

refers to the ware potato growers (not in the context of seed potato growers)

Varieties that were not released from research centers but happened to be grown for many years in certain areas of the

potato growing regions. No information was available on how and when these varieties were first introduced.

2

1

security in response to the growing population. And finally, Ethiopia is strategically

positioned to trade with the Middle East, the EU and the neighbouring African countries;

hence, improved potato varieties are needed to address the needs of local and international

customers.

Although the problem of low adoption is well recognized by the EIAR, the causes for the low

adoption is not yet empirically investigated. The EIAR cites shortage of “improved” seed and

poor seed supply system as the main limiting factors (i.e., supply side constraint,

Gebremedhin et al., 2008). However, the lack of understanding about the underlying problems

of low adoption can only put further scrutiny in the existing research – farmer relationship.

We argue that the problem of the low adoption, to a larger extent, relate to the market

conditions that the potato research centers fail to include in their breeding programs.

Contributing to the problem of low adoption is the lack of (insufficient) information exchange

between the research centers and the farmers. In the absence of proper information exchange

about the quality characteristics of the released varieties, farmers may have difficulties to

understand the quality management practices that need to be followed. Hence, the uncertainty

surrounding the characteristics of the new technology3 may force farmers to continue growing

the LVs in which they have full knowledge of all the necessary agricultural practices.

The paper may add to the existing literature in the following ways. First, although voluminous

of literature exist on the problem of low adoption, most of the studies focus on endogenous

factors (individual characteristics of the adopter, Kevane, 1996). Of the endogenous factors,

risk appetite of the adopter is considered a key determinant for low adoption (Abadi Ghadim

and Pannel, 1999; Feder and Umali, 1993). However, implicit to this assumption is that the

technology being adopted or the knowledge transfer system is correct. For example, Sall et al.

(2000) claim that the literature has omitted some critical factors related to adoption and found

out that exposure to information, membership in an organization, growing cycle, cooking

quality, height of the variety and initial impression of the variety were important factors for

rice variety adoption. We attempt to add to this strand of the literature by examining some

exogenous factors (from a supply chain perspective) that may lead to the problem of low

adoption.

Second, from the perspective of intensifying smallholder participation to a high value market,

this paper provide answers on how quality is viewed and information about product quality

characteristics is exchanged in less developed agrifood chains. Understanding of such

indigenous quality control and information exchange mechanisms could serve as a

springboard to find options for improving the performance of local supply chains. Indigenous

quality control and information exchange mechanisms involving smallholder farmers have

received little attention. In this regard, evidence from the potato supply chain is a good case in

point: (1) as potatoes are produced and supplied by a large number of smallholder farmers in

many developing countries; (2) due to the nature of the crop (perishable, bulky and costly due

to a large volume of planting material needed), potato production and marketing requires high

level of coordination; and (3) there is a rising urban population and an increasing demand for

high quality potatoes in many developing countries (Kaganzi et al., 2009; Devaux et al.,

2009).

3

Technology is used in this paper to refer to new varieties released from the research centers

2

To analyse the causes for low adoption , we set the following specific research questions. (1)

How the quality of existing potato varieties is characterised using farmers’ knowledge? Is

there any significant quality difference between the main LVs and the RVs? (2) How the

quality characteristics of the LVs and RVs are aligned4 to the potato growers’ production and

market decisions and the quality preferences of downstream actors? (3) What quality control

and information exchange mechanisms are used in the potato supply chain?

Concepts from product quality, indigenous knowledge and agricultural innovation systems are

used to understand the causes of low adoption by systematically analysing the main

production and market-related quality characteristics of both the RVs and the LVs, and how

information on product quality is exchanged and controlled in less developed agrifood chains.

The remaining sections of the paper are organized as follows. Section two provides some

background information about the organization of agricultural research and extension systems

in Ethiopia and the relationship between the different actors in the potato supply chain. The

subsequent sections present the literature review, methodology, results and discussion and

conclusions.

2. Background

2.1.Overview of the agricultural research and extension systems in Ethiopia

Agricultural research in Ethiopia was initiated in the 1940’s and later evolved into an

organized form in the 1960’s with the establishment of the then Institute of Agricultural

Research (IAR) in 1966. The Ethiopian Agricultural Researches (EARS) consist of three

actors – the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), the Regional Agricultural

Research Institutes (RARIs), and Higher Learning Institutions (HLIs). The EIAR is

responsible for the supply of improved agricultural technologies, popularization of improved

technologies, coordination of the national agricultural researches, and capacity building of

researchers (www.eiar.gov.et). The EIAR carries out about 86% of the total public

agricultural research activities in the country.

Despite the claim that public sector investment in agricultural research has declined in many

African countries, the 2008 figure put Ethiopia as the 7th largest country in agricultural R&D

investment (USD 69 million) and the second largest in terms of employing fulltime research

staff in Africa (Beintema and Stads, 2011). Similarly, Spielman et al., (2010) reported over 50

million USD (2% of GDP) is being spent every year related to agricultural extension services.

Agricultural research centers in Ethiopia pay little attention on researches related to value

chain development (Abate et al., 2011). In areas where research is carried out, technology

adoption has been slow, crop yields are very low and no sustained breakthroughs are seen

(Abate et al., 2011). Extension is the principal model used for knowledge transfer. However,

primary data collected from extension workers and farmers reveal that the unidirectional

model of extension systems in Ethiopia failed to live up to the expectation that the extension

model (1) has not been participatory, (2) gives little consideration to farmers’ experiences and

knowledge, (3) extension workers lack up-to-date training, and (4) often faces with the

problem of elite capture (biasness towards the richer farmers) (Belay, 2003, 2004).

4

Alignment is used in this paper in the context of matching of preferences

3

2.2.Overview of the Ethiopian potato supply chain

In this section we briefly explain the Ethiopian potato supply chain and the major actors.

a. Research

Center

b. Specialized

seed growers

i. Hotels,

restaurants

The weakest link

c. Informal

seed market

d. Ware

Growers

e. Collecting

wholesalers

f. Stationed

wholesalers

g. Retailers

h. Household

consumers

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of the dominant potato supply

chain

a. Research center - the Potato Research Division of national or regional research centers

are responsible to disseminate the technology to the potato growers. Accordingly, newly

released varieties are delivered to selected potato farmers called “specialized seed

growers”. The improved seed is then multiplied by the seed growers with the intention of

further disseminating the technology to the ware potato growers. There is a close link

between the research division and the specialized seed growers.

b. Specialized seed growers – These are seed growers organized as farmer field schools

(FFS), farmer research groups (FRG) or seed cooperatives by the potato research division

in the highland areas. They get improved seed from the national or regional research

center (as a gift). After multiplication, the specialized seed growers largely sell the seed to

NGOs and agriculture offices who in turn give the seed to the ware potato growers in

other regions. So far the role of traders (wholesalers and retailers) in linking the

specialized seed growers with the ware potato growers has been very minimal.

c. The informal seed market- This is the market where the majority of ware potato growers

source potatoes to be used as seed. Over 98% of ware potato growers’ buy seed from

informal sources (Gildemacher et al., 2009). For the informal market, the name of the

variety and the area of production are important for the ware potato growers.

d. Ware potatoes growers - There are two types of potato growers in the region subsistence and commercial growers. The subsistence growers grow in a small plot of

land and use potato for household consumption and to generate some cash by selling into

the immediate (nearby) markets. When the subsistence farmers sell their potato to the

nearby markets they are often forced to sell via town middlemen. The commercial

growers on the other hand are highly market oriented and produce at larger volume. They

sell at farm gate to long distance traders (collecting wholesalers). They often use the

institution of (rural) middlemen to purchase potatoes from growers. The rural middlemen

unlike that of town middlemen live close to the growers and are either have family ties or

belong to same clan with those growers. Most of the ware potatoes are sold at farm gate.

e. Collecting wholesalers – they are long distance traders located close to the potato

growing regions. They buy directly from growers and supply to the central market and to

other major cities in the country. They mostly purchase potatoes from (commercial)

growers at farm gate.

4

f. Stationed wholesalers – These are the buyers located at the central market. They buy

potatoes from collecting wholesaler in bulk and then resale to retailers, hotels, restaurants,

and cafes.

g. Retailers –small traders that buy potatoes in smaller quantity from wholesalers located at

the central market place and who ultimately sell to household consumers.

3. Conceptual framework

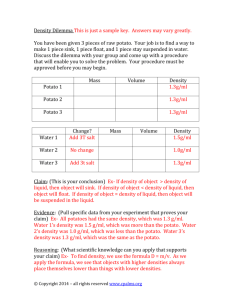

Fig 2. Presents the conceptual framework of this paper. Having this conceptual framework in

mind, we explain the relationship between the different boxes using the literature from

product quality, indigenous knowledge and agricultural innovation systems.

A

B

Varieties

Quality characteristics

Released

Local

C

Quality preferences

Production related

Market related

Fig 2. Conceptual framework

Research centers

D

F

Growers

E

Buyers

3.1. Quality perception in agrifood supply chains

Quality is an elusive concept as it is difficult to measure as it depends on many factors, like

the nature of the product, the user of the product and the market situation (Sloof et al., 1996).

Defining quality from a supply chain perspective is even more problematic as different chain

actors may view quality differently based on what characteristics of the product they find

more or less important (see table 1).

Table 1. Interpretation of quality by various chain actors

Actor

Quality aspects

Breeder:

vitality of seed, yield

Grower:

yield, uniformity, disease resistance

Distributor:

shelf life, availability, sensitivity to damage

Retailer:

shelf life, diversity, exterior, little waste

Consumer:

Taste, healthy, perishable, convenience, constant quality

Source: Ruben et al., 2007 p. 30

The literature provides different approaches to study quality (the transcendent, production

management, economics, perceived quality - see Steenkamp, 1989:7). The literature often

define product quality in terms of its intrinsic (properties which cannot be changed without

altering the physical properties of the product – e.g., colour, firmness) and extrinsic

characteristics (properties that are product related but not part of the product –e.g., brand

names, price, Luning et al., 2002). Sloof et al. (1996) provided the distinction between

intrinsic and extrinsic properties in terms of assigned quality of a product and acceptability of

a product. Assigned quality is a result of the evaluation of the intrinsic properties of a product

and reflects the needs and goals of a user, without referring to the extrinsic properties of a

product. On the other hand, acceptability of a product is a combined effect of assigned

5

quality, extrinsic product properties and market condition. According to Sloof et al., (1996),

assigned quality may change because of changes in the criteria or changes on product

properties.

Following the above conceptualization of quality, Sloof et al., (1996) developed a quality

assignment model (QAM) (see Fig. 3). According to the model, intrinsic product properties

constitute the state of the product and are evaluated based on quality criteria imposed by a

producer or a user of the product. The QAM is based on only intrinsic quality attributes and

describes how a group of users assign quality to a particular product. Assignment of quality to

a product’s intrinsic quality attributes takes three steps: (1) perception of intrinsic properties

(using instruments or human senses); (2) evaluation of perceived quality attributes (using

instruments or human senses to determine the values); (3) appreciation of individual quality

attributes to give a uni-dimentional quality measure. Appreciation is a state of the mind. At

the latter step, weights are given to individual quality attributes or to a combination of quality

attributes. The weights may reflect the influence of socio-psychological factors determining

the attributes to be used and the order of importance of these attributes.

Intrinsic

properties

Perception

Evaluation

Appreciation

Assigned

quality

Fig.3 Quality assignment model (Sloof et al., 1996)

Referring to our conceptual framework (fig.2), B refers to the intrinsic quality characteristics

attached to each variety A. Because the definition of quality varieties depending on which

level of the chain the actor is, we grouped quality into two: production-related (production

management approach) and market-related (consumer research approach). Quality

characteristics such as yield, disease tolerance, days to mature, drought resistance, and

management characteristics are production related. On the other hand, tuber size, stew quality,

cooking quality, colour, shape, and shelf life are market related (refer table 1). The arrow

from A to B shows how potato variety (genotype), to a large extent, determines intrinsic

quality characteristics (Richardson, 1973; Howard, 1974; Long et al., 2004; Jemison et al.,

2008). These characterises are the property of the product and can be independently

determined through perception (e.g. by way of using them for many years) and evaluation.

The arrow from A to B will also help us to see whether the quality characteristics of the

different varieties, particularly those of the local and the released ones, are indeed

significantly differ as it was set in our research question 1 (section 1). Box C shows quality

preferences of the different actors. As per the QAM, quality preferences are the assigned

weights after evaluation and appreciation phases. However, in this case, the order of

importance for the different quality attributes may differ based individuals’ appreciation of a

particular characteristics of the product (for example some may prefer tuber size in relation to

the colour of potatoes and others may think differently). Identification of the quality

preferences of the different actors is critical at this stage in order to evaluate the presence of

misalignment or mismatch in preferences between the different actors (as indicated in our

research question 2, section 1).

In less developed agrifood supply chains, the problem is not only how quality is defined but

also how it is communicated. As rural economies become increasingly linked to urban and

export markets (Reardon et al., 2009), consumers’ demand for product quality information

increases (Reardon et al., 2001). However, in this era of liberalized domestic markets and

6

abolished state marketing institutions, it may be costly for the private actors to implement and

enforce formal quality control systems (such as grades and standards) for products delivered

by smallholder farmers. Hence, in less developed agrifood chains, product quality is often

judged on the spot and regulated by personal contact and informal institutions. In situations

where the markets are entirely rural and local, informal quality control mechanisms may be

used to improve the quality alignment in those supply chains (Reardon et al., 2001).

In our conceptual framework (fig. 2), the double arrows at D & E show the ideal information

flow from/to research centers to growers and buyers about the quality preferences at C. In this

regard, different information exchange mechanisms (such as variety name, production region,

etc.) may be used. Research question 3 is set to examine this relationship. If there is an

alignment (as indicated by a line) between the preferences of the three major actors, then the

improved varieties released from research centers should meet the quality requirements of

both the growers and buyers.

The role of indigenous knowledge (IK) and its implication for agricultural research

Sillitoe (1998), Sillitoe and Marzano (2009) provide an extensive review regarding IK. They

argue that research based on IK recognizes the complexity of local decision processes and

tries to integrate the local knowledge into scientific perspective. While IK lacks homogeneity

between cultures, age group, gender, and social class and is being criticised due to its lack of

defined theory providing a coherent and structured methodology, there is a growing consensus

in the literature that the interplay between science (agricultural research) and IK could lead to

a higher success rate for development projects involving smallholder farmers (Sillitoe, 1998;

Mosse, 2005; Sillitoe and Marzano, 2009). The importance of IK has long been recognized in

the field of medicine, botany, and zoology, particularly, to study taxonomic systems (i.e.,

human beings classification abilities) (Sillitoe, 1998). IK initiatives facilitate more successful

interventions through creating better understanding of local situations. Many development

programs in developing countries failed due to the use of “top-down” approaches that lack

local roots (Sillitoe and Marzano, 2009). Perhaps, in recognition to the shortcomings of this

approach, “bottom-up” paradigms, such as incorporating indigenous knowledge in scientific

studies, gradually started to take shape5.

The need for a bottom-up approach in agricultural research lies on the view that poor farmers

living in less developing countries have failed to benefit from the agricultural research outputs

as expected (Sumberg, et al, 2003). Hence, there is a renewed interest about the importance of

indigenous knowledge and end-user participation in agricultural research (Beintema and

Stads, 2011). There are generally two views on agricultural research in the literature. One

view relates to the “central source model” which assumes farmers as passive recipients of new

technology and hence follows a unidirectional flow of research, extension and adoption

process. According to Biggs (1990) – innovations are seen to arise from international

research centers then passed down to national research systems, extension agencies and

finally to farmers. In contrast, in the “multiple source model” of innovation, farmers are

considered as active innovators and information flow is multi-directional. The main feature of

the multiple source model is its acknowledgment that agricultural research and technology

promotion systems contain diverse objectives of different actors (Biggs, 1990).

In this paper, local knowledge, indigenous knowledge or farmers’ knowledge are interchangeable used

(Sillitoe, 1998).

5

7

In line with the central view model, the innovation diffusion theory (Rogers, 1983) has been

dominant for several decades. However, Biggs (1990) and the literature of Agricultural

Knowledge Information Systems (AKIS) highlight the need for integrating the local

knowledge and local processes of innovation with formal research activities. The main

argument behind this notion is that farmers have an intimate knowledge of their local

environment, conditions, problems, priorities and criteria for evaluation as part of their

farming routine than anybody else. Sumberg et al. (2003) propose some hypotheses under

what condition farmers’ (users of the technology) participation is most likely to be beneficial.

According to Sumberg et al. (2003), when the formal research and farmers’ research are

partially substitutable, no synergy effect is anticipated from participation (the additive model).

On the other hand, when there is heterophily6 between research paradigms, objectives and

methods, there is a possibility for synergy effects (the synergy model). Sumberg et al (2003)

uses the synergy model to draw the following hypotheses (table 2).

Table 2. Hypothesised relationship between heterophily and potential synergy

Degree of heterophily

Potential for synergy

Low

Low

Intermediate

High

High

Low

In our conceptual framework (fig. 2), farmers’ indigenous knowledge is introduced to

characterize the production and market related characteristics of the local and released

varieties (A). This characterization serves as a base for identifying quality preferences of both

growers and buyers. The double arrows between E & D are intended to show the importance

of participatory (bottom-up) approaches in agricultural research as suggested in the multiple

source model. This increases the likelihood of farmers’ decision to adopt the improved

varieties.

4. Methodology

Data has been collected in the context of the Ethiopia potato supply chain, with a particular

emphasis in one region. This is because variety names in Ethiopia lack standardization and are

mainly attached to local languages. Even the RVs are given local names (Cavatassi et al.,

2011). This made it difficult to know if various names refer to the same or different

genotypes. Our research design was, therefore, to focus on one region, in fact the most

important potato production region in the country, in order to avoid any problem arising from

confusion of names for possibly the same variety.

As introduced in section 1, the paper provides answers to the following research questions. (1)

How the quality of existing potato varieties is characterised using farmers’ knowledge? Is

there any significant quality difference between the main LVs and RVs? (2) How the quality

characteristics of the LVs and RVs are aligned to the potato growers’ production and market

decisions and the quality preferences of downstream actors? (3) What quality control and

information exchange mechanisms are used in the potato supply chain?

This section provides the data sources, data collection and the analytical procedures and

methods employed to answer the above research questions.

6

the degree to which two or more individuals who interact are different in certain attributes (in terms of beliefs,

education, social status, and the like) (Rogers, 1983).

8

In order to answer research question 1, data were collected from a total of 346 potato growers.

The main objective of this part of the study was to uncover the most important quality

attributes each variety possesses, not the variety per se.

Characterisation of the different potato varieties was made in the following manner. First,

variety classification was based on variety names and was made by farmers, triangulated with

information from agricultural agents, secondary data and focus group discussions. Farmer

based classification is important in understanding varietal choices (Cavatassi et al., 2011).

Following this classification, we documented seven potato varieties. Second, in an attempt to

establish relationship between variety and quality, we followed two dimensions for assessing

quality - production and market-related.

Measures for quality characteristics related to production

Productivity/yield – Kg/Timad (=0.25ha)

Disease resistance –very low to very high (1-5)

Drought resistance – very low to very high (1-5)

Intensity of quality management practices – very low to very high (1-5)

Maturity period – in days

Measures for quality characteristics related to marketing

Keeping ability – in weeks

Tuber size – very small to very large (1-5)

Tuber shape – full round, semi oval, oval (1-3)

Cooking quality – very low to very high (1-5)

Stew quality – very low to very high (1-5)

Even though variety names are short-lived and can simply die out, our systematic approach

allowed us to understand the relatively stable quality characteristics each variety possesses.

Third, growers were asked to evaluate different varieties on their production-related quality

attributes and market-related quality attributes. The quality characteristics were identified by

reviewing the literature on potato quality (Richardson, 1973; Howard, 1974; Long et al.,

2004; Jemison et al., 2008) and after assessing their relevance to the local context in a pilot

study.

Our conceptualization of quality follows the definition given by, among others, Lancaster

(1966, 1971) where he defines quality as a function of objectively measurable properties of

goods. He further argues that a good possesses multiple characteristics and many

characteristics will be shared by more than one good. Unobservable characteristics of potatoes

were not considered in our analysis as information on these attributes is rarely conveyed along

the chain. Molnar and Orsi (1982) suggest that it is not necessary to investigate every property

of a product but only those important ones required to determine product quality.

To answer the second research question, we needed to understand the quality preferences of

the different chain actors. The characterisation of varieties in the first part was simply to

obtain an account of how farmers perceive a particular variety and was not meant to indicate

individual preferences. In this part of the study, we were interested to know individual

preferences for the different quality attributes. Growers were asked to allocate 100 points to

the different production related quality characteristics. This follows the quality assignment

model (fig. 3) that farmers (users) first perceive and evaluate the different varieties (as it was

done in question 1) using their experiences. Then appreciation follows in order to provide

weights for the different quality measures (ranging from 0 to 100 points). These weights are

assumed to reflect individual preferences and may vary from person to person based on a

number of factors. For this part of the study, we collected additional data from a randomly

9

selected 114 potato growers regarding their preferences to production-related attributes.

Similarly, downstream actors were asked to give their preferences as to the market-related

quality characteristics. Because collecting wholesalers largely supply potatoes to the central

market, Addis Ababa, we purposely selected buyers at the central market. Accordingly we

were able to collect data from 10 major wholesalers (from a population of about 26

wholesalers), 13 retailers and 11 hotels stationed in the capital who were willing to share the

information we needed.

The questions for growers were stated as “Please distribute 100 points over the different quality

attributes that you may take into account when you select a particular potato variety to grow. Give the

highest value to the most important quality attribute, the second highest value to the second most

important quality attribute, etc. The total of all values should be equal to 100 points”. Similarly, the

questions for downstream actors were stated as “Please distribute 100 points over the different quality

attributes that you may take into account when you are buying potatoes. Give the highest value to the

most important quality attribute, the second highest value to the second most important quality

attribute, etc. The total of all values should be equal to100 points”

For the third research question, both the growers and the downstream actors were asked to

choose what kind of information exchange mechanisms they use to identify the quality of

potatoes when they sell/or buy. Moreover, the growers were asked about the kind of quality

control mechanisms they use in their relationship with the collecting wholesalers.

The survey was conducted in person using structured questionnaire by trained personnel, who

had a first degree either in sociology or management. Supervision and quality checks were

made on the spot by the principal investigator.

5. Results

5.1.Growers’ evaluation of quality characteristics

5.1.1. Characteristics of the sampled potato growers

Table 3 provides the main characteristics of the study areas and the surveyed growers. The

distribution of sub districts and growers included in the survey follow the patterns in the level

of production and the type of potato variety grown. Since our focus was on household heads,

only 14 women headed households happened to be included in the random sample. From the

result, the average age (year), education level (school year), land (ha) and livestock (TLU)

owned were 37, 6, 1.5, and 8.1, respectively. About 56% of sampled potato growers lived in a

house with a corrugated iron sheet. The descriptive statistic also shows a dependency ratio of

1.3 and an average family size of 10. Over 33% of the respondents had two or more wives.

Compared to the sample average, those growers practicing polygamy were older farmers (42

years of age) and less educated (4 school years) with an average family size of 14. In terms of

access to information, 67% and 65% of surveyed growers reported to have a mobile phone

and radio respectively. Potato farming on average generated about 50% of the total cash

income for the sampled households. There is low agro-ecological variability between the three

districts in the sample.

10

Table 3. Characteristics of the study areas and sampled growers

General information

Sub districts (Kebeles)

Agro ecology (altitude above sea level in meters)

No. of growers in the sample

Personal and household characteristics

Sex

Male

Female

Marital status

Unmarried

Widow

Married (1 wife)

Married (>=2 wives)

Position of the respondent

Head of the household

Other

Age (years)

Family size

Education of the respondent (years in school)

Highest education in the family (years in school)

Dependency ratio{(<=14yr+>64yr)/(15-64 yr)}

Wealth (as approximated by)

At least a house with corrugated iron sheet (% yes)

Land (owned) in ha

Domestic animals in equivalent unit (TLU7)

Having a mobile phone (% yes)

Having a radio (% yes)

Having a TV (% yes)

Cash income from potato sales* (previous year)

Mean value (in ETB**)

% of potato cash income (from total cash income)

Distance to the central market, Addis Ababa (km)

Total

16

346

Shashemene

8

1700 - 2300

228

Siraro

5

1500 -1900

75

Shala

3

1500 - 2075

43

332

14

214

14

75

0

43

0

12

1

218

115

9

1

159

59

1

0

39

35

2

0

20

21

342

4

36.8

9.6

5.7

8.3

1.3

224

4

37.8

9.1

6.4

9.3

1.2

75

0

35.7

10.3

4.1

6.3

1.4

43

0

33.6

11.0

4.5

6.4

1.5

55.8

1.5

8.1

66.8

65.0

9.5

67.5

1.2

4.9

66.2

69.3

12.3

28.0

2.1

11.0

60.0

53.3

1.3

41.9

2.1

19.9

81.4

62.8

9.3

9,905

49

6,233

40

250

13,324

65

300

23,412

68

280

* Potatoes not sold till the time of the interview were not included; **1€ ~23ETB

5.1.2. Characterising varieties using farmers’ knowledge

Before we assess the mean scores given by the growers, we first present their knowledge on

the different quality attributes following the QAM discussed in section 3. Hence, table 4 and

5 present the percentage of sampled growers who had knowledge on the production and

marketing related quality characteristics of the different varieties respectively. The LVs Nechi

Abeba, Agazer, and Key Dinich were common to the majority of potato growers. Of these, the

production and market characteristics of Nechi Abeba seem overwhelmingly known by

growers followed by Agazer than particularly those of the three released varieties (Bule,

Gudane, and Jalene). We believe that the number of growers who had knowledge on each

variety was fair enough to make the characterisation on the seven varieties. Moreover, we

focused on observable quality characteristics which would make it easier for the growers’

evaluation task.

7

Tropical livestock units, used as a common unit to describe livestock numbers of various species as a single figure that

expresses the total amount of livestock present. Accordingly oxen/cow=1TLU; Calf=0.25TLU; Heifer=0.75TLU;

sheep/goat=0.13TLU; Young sheep/goat=0.06TLU;donkey=0.7TLU

11

Table 4. Growers’ knowledge on the production related quality characteristics (PRQCs)

Yield

of

57

89

38

25

12

22

5

Do you know the

Agazer?

Nechi Abeba?

Key Dinich?

Key Abeba?

Gudane?

Jalene?

Bule?

Percent Yes (N=346)

Disease

Drought

tolerance of

tolerance of

71

72

99

98

64

62

64

59

22

20

39

32

21

19

Maturity day

of

72

99

65

60

23

38

21

Management

intensity of

71

98

62

54

21

35

17

Table 5. Growers’ knowledge on the market related quality characteristics (MRQCs)

% Yes (N=346)

Do you know the

Agazer?

Nechi Abeba?

Key Dinich?

Key Abeba?

Gudane*?

Jalene*?

Bule*?

Cooking quality of

77

99

72

69

25

41

34

Keeping ability of

62

89

53

47

16

27

14

Stew quality of

75

99

69

64

19

37

29

Taste of

78

99

72

67

25

41

34

Tuber size of

79

99

77

73

31

50

36

*released varieties

5.1.2.1.Evaluation of production related quality characteristics(PRQCs)

Evaluation of the PRQCs is reported on table 6. Accordingly, the yield per “Timad” was

highest for the RVs Jalene (JL) and Gudane (GD) followed by the LVs Nechi Abeba (NA)

and Agazer (AZ). Key Abeba (KA) and Key Dinich (KD) were the lowest yielding varieties

as reported by sampled growers. The RVs, with the exception of Bule (BL), were better with

respect to yield characteristics. In terms of disease tolerance, the mean scores of RVs are

higher than the LVs. This is, of course, not a surprising result given the focus of the research

institutions on yield and disease tolerance aspects.

Table 6. Average results of PRQCs as evaluated by growers

Variety

AZ

NA

KD

KA

GD*

JL*

BL*

N

Chi-Square

df

Asymp. sig

Yield

(100kg per

Timad)

26.5 (10.5)

31.2 (11.8)

21.7 (8.3)

21.5 (7.8)

43.8 (18.3)

45.7 (20.1)

24.4 (11.9)

24

34.46

3

.000

Days to maturity

(No. of days)

88 (10)

101 (15)

70 (11)

82 (15)

122 (16)

123 (18)

112 (20)

67

157.594

3

.000

Tolerance to

disease Scale

(1-5)

3.7 (1.2)

3.5 (1.2)

2.6 (1.2)

1.8 (0.9)

4.1 (1.0)

4.2 (1.2)

3.8 (1.1)

63

43.57

3

.000

Tolerance to

drought

Scale (1-5)

3.8 (1.1)

3.9 (1.2)

2.8 (1.2)

2.2 (1.1)

3.8 (1.2)

3.7 (1.3)

3.5 (1.4)

56

2.56

3

.464

Management

intensity

Scale (1-5)

3.7 (1.0)

4.3 (0.9)

2.9 (1.1)

3.1 (1.2)

3.7 (1.3)

3.7 (1.3)

2.8 (1.3)

56

2.563

3

.464

*released varieties (RVs); () STD

In terms of tolerance to drought, the scores given to the LVs NA and AZ were similar to the

RVs GD and JL. Differences exist with regard to maturity period. The two RVs GD and JL

mature in 123 days with a STD of 17 days compared to the dominant LV, NA, which takes

about 100 days to mature with a STD of 15 days. In terms of management practice intensity,

12

the LVs NA and AZ scored higher than the RVs, GD and JL. To see if there is a difference in

PRQCs between the seven potato varieties, we run the Friedman Test (Friedman, 1937).The

result suggests the presence of an overall statistically significant difference (p<0.01) between

the mean ranks of yield, days to maturity, and disease tolerance.

5.1.2.2.Evaluation of market related quality attributes (MRQCs)

Table 7 presents growers’ evaluation of MRQCs. Scanning through the results, the mean

scores for cooking quality and taste are nearly the same across varieties implying that both

seem to be understood in a similar way. In terms of cooking quality and taste, the LV AZ

scored highest followed by the RVs BL and JL. KA was given the lowest score. Growers say

when they eat variety AZ as boiled it is dry in the mouth and tastes very good. In terms of

keeping ability, the RVs BL, GD and JL scored highest while the LVs KA and NA scored

least. In terms of stew quality, NA scored highest whereas BL, KD and KA were rated least.

With regard to tuber size, JL and GD were given the highest scores followed by the dominant

LV NA. As to colour, there was no major variability between the main varieties. Except BL

and KD, which have red colour, the others generally have white colour. Regarding tuber

shape, except AZ and KD which have oval shape, the others generally have a round and semiround shape.

Table 7. Average results of MRQCs as evaluated by growers

Variety

AZ

NA

KD

KA

GD*

JL*

BL*

Tuber size

Scale(1-5)

Stew quality

Scale (1-5)

Cooking quality

Scale (1-5)

Keeping

ability(week)

Taste

Scale(1-5)

3.4 (0.7)

3.9 (0.3)

2.3 (0.9)

2.2 (1.1)

4.4 (0.6)

4.8 (0.4)

3.0(1.0)

3.8 (1.0)

4.8 (0.6)

2.5 (1.1)

2.6 (1.1)

3.3 (1.0)

3.4 (1.1)

2.2 (1.3)

4.6 (0.8)

3.9 (0.9)

3.1 (1.1)

2.2 (1.0)

3.5 (1.1)

3.9 (1.1)

3.8 (1.4)

11.5 (5.5)

8.7 (5.3)

11.1 (5.6)

8.5 (4.5)

13 (7.6)

11.9 (6.6)

15.6 (7.6)

4.7 (0.6)

3.9 (0.9)

3.2 (1.1)

2.0 (1.0)

3.3 (1.0)

4.0 (0.9)

4.2 (1.1)

*Released varieties () STD

In terms of keeping ability, it is shown that the three RVs have the potential to be kept longer

than the LVs, particularly compared to the dominant LV NA. However, ware potato growers

generally don’t keep potatoes in their storages, perhaps, due to the lack of modern storage

systems and the highly susceptibility of the traditional storage systems 8 for high quality losses

(transpiration, respiration, sprouting, soil borne diseases, and physical damages). As a result,

most of the growers tend to sell their potatoes immediately after harvest (within 24 hours of

harvest). Because taste and cooking quality are similar and keeping ability is not considered

important for the aforementioned reason, they are dropped for further analysis. The Friedman

Test result shows that there is an overall statistically significant difference (p<0.01) between

the mean ranks of tuber size, stew quality, and cooking quality.

The fact that the varieties have significance quality differences between each other leads to

our second research question. More specifically, how are the quality characteristics of each of

the varieties are aligned to the needs of the different supply chain actors?

5.2.Analysis of the alignment of quality requirements of different actors

In section 2 (figure 1), we have identified the main actors in the potato supply chain in the

ware potato sector. We have also shown how farmers characterised the different potato

varieties based on their knowledge (tables 6 and 7). In this section, we present the relative

8

Such as postponed harvesting (i.e., leaving the tubers in the soil), local granary, keeping on bed, or on the floor

of their house ( Endale et al., 2008; Hirpa et al., 2010)

13

preferences of both growers and downstream actors towards those quality characteristics in

order to evaluate the alignment of preferences between the different actors (including the

research priorities of the state research centers.

Table 8. State research priorities

Quality Requirements

Yield

Ecological adaptability

Disease tolerance

Priority

1

2

3

Source: Gebremedhin et al. (2008)

5.2.1. Quality preferences of growers

For this part of the study, we collected additional data from a randomly selected potato

growers using a structured questionnaire specifically designed to identify growers’

preferences. Table 9 provides the descriptive statistics for sampled growers. The mean age of

growers that provided the weights was about 37 years and 74% of them had education at the

level of either junior high school or above. Moreover, 63% of the growers had mobile phones.

These characteristics are considered very important to effectively assimilate and evaluate the

different quality attributes.

Table 9. Mean value of growers’ characteristics (N=114)

Sex (%)

Age

(year)

Male

Female

36.5

99.1

0.9

Education level (%)

primary

junior

high

school

school

school

26.3

43.9

22.8

some

college

7

Land

size

(in ha)

Mobile

phone (%

yes)

0.8

62.3

Table 10 shows the weights assigned by growers for PRQCs. From the results, characteristics

related to yield was given the highest weights followed by days to maturity and disease

tolerance. Characteristics related to quality management intensity and drought tolerance were

given lower scores. Referring back to the test statistics on table 6, the seven varieties were not

significantly different with regard to the two characteristics. Perhaps, the availability of cheap

family labour in most rural areas could explain the former. Based on the result displayed on

table 10, we may generalize that growers prefer a high yielding, short maturing and a disease

tolerant variety in their order of importance.

Table 10. Growers’ assigned weights (from 100 points)

PRQCs

Yield

Days to maturity

Disease tolerance

Drought tolerance

Quality management intensity

Mean (N=114)

40.1

29.7

20.3

9.8

0.1

SD

12.9

13.9

12.8

10.6

0.9

However, no one variety reported before has all the three quality characteristics together.

Even if there exists there is no guarantee that this variety will be liked by buyers in the

downstream part of the chain. The next section discusses this point.

5.2.2. Quality preferences of downstream actors

Table 11 summarizes the description of traders who buy directly from growers in the study

area. On average the surveyed traders had 8.8 years experience in potato trading. A collecting

wholesaler on average hired 30 people (men-hour) per day due to the fact that potatoes were

14

harvested by hired daily workers. 78% of collecting wholesalers’ revenue during 2009/10

came from potato sales. The average volume sales by a collecting wholesaler during the same

year was 2,478 tons, with 65% of them delivered to the central market, Addis Ababa; whereas

retailers from the potato growing region often sold to the local consumers in the immediate

market.

Table 11. General description traders who directly buy from growers in the study areas

Mean values

Experience in potato trade (year)

Mean number of workers hired per day

Potatoes delivered per year per trader* (tons)

Potato sales (% total revenue)

Sales outlet (%)

Nearby Markets (<=75 Km )

Central Market (250 km)

Other Distant Markets (>75 km)

Total (N=49)

Retailer (N=12)

Collecting

wholesaler (N=37)

8.8 (5.7)

23.5 (29.2)

1974

72.7

6.4 (3.7)

5.1 (3.3)

428

55.4

9.6 (6.0)

29.5 (31.3)

2478

78.2

38.8

49

12.2

91.7

0

8.3

21.6

64.9

13.5

*own computation () STD

As far as the buyers located at the central market are concerned, the mean purchased volume

during the year 2009/10 was 957 tons for stationed wholesalers, 42 tons for retailers and 7

tons for hotels. While all sampled stationed wholesalers knew production region of potatoes

they purchased none of the hotels and only 15% of retailers did know about it. The sampled

stationed wholesalers on average purchased 65% of their potatoes originated from the study

area.

Table 12.General description of potato buyers at the central market place (Addis Ababa)

Mean values

Amount purchased previous year (in tons)

Place Purchased (%)

Addis Ababa (central market)

Addis Ababa (Supermarket)

Knew production region of potatoes purchased (% yes)

If yes, potatoes purchased originated from (in %)

West Arsi Zone (the study area)

East Arsi zone (South East)

Holeta area (West)

Gojam (North West)

Total

(N=34)

Hotels

(N=11)

Stationed

wholesalers (N=10)

Retailers

(N=13)

299.5

6.8

956.8

42.1

91.2

8.8

35.3

72.7

27.3

0

100

0

100

100

0

15.4

65.8

25.3

7.2

1.7

0

0

0

0

65

28

11.7

5.3

70

26.5

7

0

Table 13 provides an overview of buyers’ assigned weights for market related characteristics.

Because 65% of potatoes purchased by the collecting wholesalers were delivered to the

stationed wholesalers located at the central market, we only focused on the latter to assess the

relative quality preferences. From the results, it seems that retailers prefer most tuber colour

followed by tuber size but not for tuber shape. On the other hand, stationed wholesalers give

priority for tuber size followed by colour and keeping ability of the tuber. For hotels, colour

received the highest score followed by tuber size and tuber shape. Generally, cooking quality,

price, stew quality, and keeping ability were assigned low points by buyers. One surprising

result relates to stew quality. Almost all household consumers in Ethiopia use potatoes for

making a stew. However, the result doesn’t seem to reflect it. One possible explanation is that

stew quality characteristics may have been intermingled in other quality characteristics such

as tuber size. In general, we can say that tuber size and colour are the most important quality

characteristics for the downstream actors’ purchase decision.

15

Table 13. Downstream actors’ assigned weights for MRQCs

Mean value of weights (from 100

points) for

colour

tuber size

keeping ability

tuber shape

stew quality

purchase price

cooking quality

Total

(N=34)

37.3

32.8

7.2

6.9

6.2

5.8

4.1

Hotel

(N=11)

35.4

32.6

5.0

15.8

6.8

2.1

2.3

Stationed

wholesaler (N=10)

30.3

38.2

11.5

6.0

6.7

2.0

5.3

Retailer

(N=13)

44.2

28.8

5.8

0

5.4

11.9

4.6

5.2.3. Quality alignment between state research centers, growers and

downstream actors

As indicated on table 8, the research cetnters release new potato varieties based on three

quality criteria – yield, disease tolerance and agro-ecological adaptability (Gebremedhin et

al., 2008). With regard to agro-ecological adaptability, the three RVs included in this study

can be grown at an altitude ranging from 1600 - 2800m (JL), 1700 – 2700m (BL), and 1600 –

2800m (GD) (Gebremedhin et al., 2008). This implies that all the three RVs are technically

adaptable to the agro-ecology of the study areas. As shown above, the two RVs JL and GD

are rated as high yielding and high disease tolerant.

Our data suggest tuber size and colour are the most important quality criteria both for growers

and buyers. Further analysis revealed that the desired colour by all of the buyers is white.

With regard to tuber size, 80% of wholesalers prefer large tubers and about 85% retailers

prefer small, medium, or large size tubers instead of very large tubers. Similarly, 73% of the

sampled hotels prefer either medium or large size tubers, and only the remaining 27% prefer

very larger tubers. Generally, larger tuber size potatoes are preferred to small, medium, or

very large tubers by both growers and traders. Though tuber shape was not as such found to

be an important selection criterion by the major supply chain players, all wholesalers and

retailers in the sample preferred round shape tubers and only 46% of the hotels preferred oval

shape tubers. In terms of colour, there is no much difference between the most common LVs

and RVs, implying that the main difference lies on tuber size. Generally, the two main RVs

seem to have very large tuber size. From table 14, it seems that very large tuber size potatoes

are less desirable by both growers and buyers.

Table 14. Some desired quality characteristics by major participants of the potato chain

Mean values

Desired colour

Desired tuber size (mean value)

large

very large

medium

small

Desired tuber shape (mean value)

round

semi round

oval

indifferent

Growers

(N=114)

White

Hotel

(N=11)

White

Stationed wholesaler

(N=10)

White

Retailer

(N=13)

White

61.4

28.1

10.5

0

36.4

27.3

36.4

0

80.0

20.0

0

0

46.2

15.4

15.4

23.1

67.5

15.8

14.0

2.6

54.5

0

45.5

100

0

0

100

0

0

To examine the optimal tuber size, we further collected sample potatoes from two potato

quality categories. One quality category, based on tuber size, was meant for retailers who

generally sell to household consumers (we call it “second class”) and the other category was

meant for hotels and supermarkets (we call it “first class”). We randomly selected 25 first

16

class potatoes that were available for supermarkets and hotels, and 40 second class potatoes

that were available for retailers. All the sampled potatoes were selected randomly from the 10

wholesalers included in our sample. Accordingly, the mean tuber size available for retailers

and for hotels and supermarkets is significantly different (p<0.001). This further reinforces

the significance of tuber size in grading the quality of (ware) potatoes.

Table 15. Optimal tuber size

Tuber size

(mm)

Type of buyers

N

Class 1: Supermarket & Hotels

Class 2: Retailers

40

42.54

25

57.28

Levene's Test

Independent Samples Test

Tuber size

(mm)

Equal variances assumed

Mean

SD

Std. Error Mean

4.877

0.771

6.516

1.303

t-test for Equality of Means

F

Sig.

t

df

Sig. (2-tailed)

1.437

0.235

-10.402

63

0.00

Taking the above results and the weights assigned by the downstream actors, we can better

explain why certain varieties are more preferable than others. It seems clear that the LV NA is

very popular by both growers and downstream actors particularly compared to that of the

RVs. It has large tuber size (average score of 3.9), white in colour, round in shape, and scored

the highest in terms of stew quality (mean score 4.8). On the other hand, variety JL (mean

tube size score 4.8) and GD (mean tuber size score 4.4) seem over the desired tuber size level

as perceived by sampled growers. When asked about the problem of very large tubers, the

response from both growers and buyers was that internal quality would compromise as the

tuber size gets very large. Moreover, since household consumers in general buy in smaller

quantities, retailers generally don’t like very large tubers as it creates measurement problem 9.

All these factors seem to have led the LV NA as the most desired potato variety in the region;

it has been consistently grown by more than 80% of sampled growers over the last five years

(see table 16). On the other hand, the RVs GD and JL were the least grown varieties during

those years. The seemingly increased percentage during 2009/10 season for the RVs was due

to the fact that one NGO supplied the RVs to some growers free of charge.

Table 16: Growers’ experience in growing the different potato varieties

Did you grow the

following potato varieties?

AZ

NA

KD

KA

GD

JL

BL

2009/10

49.1

81.2

21.4

4

9.5

22.3

1.7

Percent yes (N=346)

2008/9

2007/8

2006/7

46

42.8

35.3

84.1

82.1

80.3

25.7

24.6

20.5

6.4

6.6

9.5

2.6

1.7

1.2

2.9

2

1.2

2.9

2.6

2.9

2005/6

37.3

82.1

23.7

30.6

0.9

0.3

5.5

5.3.Quality control and information exchange in the potato supply chain

9

For example, should a consumer wants to buy 1kg of potatoes then putting 1 tuber could weigh a bit less but

making it two could weigh well over 1kg.

17

5.3.1. Quality control mechanisms

No third party or publicly owned formal quality control mechanisms were observed in the

potato supply chain. Rather, different (informal) quality control mechanisms have been

practiced to govern the relationship between growers and collecting wholesalers. One way of

controlling the quality of potatoes is visiting of the potato fields by the buyer or his agent to

verify quality in person before making any purchase commitment. Most of the time,

agreement of sales between the buyer and the grower is reached before harvest. Once the

buyer is satisfied with the quality of potatoes on the field then the harvesting task is the next

concern as it may pose additional quality risks related to prematurity, mechanical damages

and the freshness of potatoes. As a consequence, buyers often opt to undertake the harvesting

task by themselves.

Table 17 provides a summary report about such practices in the study area. 67% of buyers did

visit the potato fields before harvest and 56% of the respondents replied that harvesting was

done by the buyer. In 64% of the time, the level of quality was measured from the buyer’s

point of view or that of his agents (middlemen). It was only in 26% of the time that both the

buyer and the grower mutually decided the quality level of potatoes.

Table 17: Quality control mechanisms between growers and collecting wholesalers (N=346_)

Did your main buyer know (visit) where you grew the potatoes sold last season? (% yes)

Who did the harvesting of the potatoes sold in the previous year? (% yes)

The buyer himself

You (the grower)

Who measured the quality of potatoes sold in the previous year? (% yes)

The buyer himself

The middleman

Joint consent of the grower and the buyer

You (the grower)

Third party arbitration

66.9

55.6

44.4

36.1

28.0

26.3

9.2

0.3

The sampled wholesalers and retailers in the central market reported a number of problems

related to potato quality. Supplying prematured tubers, spoilage losses, blackening of tuber

and physical damage during harvesting were highlighted as quality problems in their order of

importance. We also observed prematured potatoes during our visit to the wholesale market. It

was learned that farmers tempted to harvest potatoes earlier than required in order to make the

potato field ready for another crop. This explains why many collecting wholesalers are

increasingly involved in visiting potato fields and finally in harvesting activities.

5.3.2. Information exchange mechanisms

Once potatoes are harvested, they have to be delivered fresh (for the next day) to the central

market. Buyers at the different level of the chain had no proper infrastructure (such as cold

storages) to minimize the risk of quality loss. This presupposes the need for an efficient and

effective information exchange mechanism between collecting wholesalers located at the

production region and those of stationed wholesalers and retailers located at the central

market. Our data from stationed wholesalers, retailers and hotels revealed that they use

production region to screen quality. However, the problem with this kind of information

exchange mechanism is that it lacks specificity, particularly when several varieties, having

different quality characteristics, co-exist in one region. On the other hand, in the potato

growing region, knowledge of variety names is important and serves as a quality signal in the

relationship between growers and collecting wholesalers. Here, the collecting wholesalers

play a key role in facilitating the information exchange. The surveyed growers revealed that

before collecting wholesalers actually observe the potatoes and evaluate other main quality

18

attributes (such as tuber size) on the farm, they first ask about the type of potato variety

grown. This happened in about 94% of the time during 2009/10 season(s).

Table 18. Type of information collecting wholesalers ask priori (N=346, % yes)

Variety name

Inorganic fertilizer (amount & time of application)

Pesticides (amount & time of application)

Tuber size

Tuber colour

94.4

10.9

5.6

99

91.8

Once they get variety information the buyers start to inquire further for important quality

attributes, such as tuber size. As shown on table 18, tuber size and colour found to be very

important unlike the unobservable quality characteristics. High transaction costs, lack of

awareness by the final consumers, absence (or ineffectiveness) of quality regulations, and/or

little access to international market could be responsible for the low importance given to the

unobservable quality characteristics.

6. Discussion and conclusion

6.1.Discussion

We presented a conceptual framework that could help to systematically analyse quality

alignment and thereby the problem of low adoption, particularly, in situations where formal

quality classification is lacking. The conceptual framework uses the local context of defining

quality (variety) and then translates it to the more generic quality characteristics that may

have greater influence on the growers’ adoption decisions. This approach is important to

narrow down differences in quality interpretation and to facilitate information exchange

between the different chain actors. In addition, the conceptual framework attempts to show

how the product, characteristics of the product and the preferences of supply chain actors can

be systematically analysed using a single framework. It incorporates two approaches of

studying quality - the product management approach (as product characteristics are evaluated

based on the criteria imposed by the growers) and a consumer research approach (as buyers

at the different level of the chain evaluated and assigned weights for the different quality

characteristics of the product). However, the conceptual framework does not explicitly show

how individual characteristics can influence quality preferences (variety selection) as the

paper mainly focused on exogenous factors that could lead to low adoption.

The problem of low adoption has been largely associated to individual factors such as risk

preferences, land endowments and education level, and to institutional factors like credit

constraints (Winters et al., 2006; Benin et al., 2006). For example, in the Ethiopian case,

Dercon and Christiaensen (2011) reported fear of taking risky production technologies while

Cavatassi and Lipper (2011) claim access to markets and social capital as drivers for

improved variety adoption in addition to risk factors. Our contribution to this strand of the

literature lies on the importance of market characteristics for improved variety adoption and

the use of local knowledge in understanding important quality characteristics that could

influence smallholder farmers’ production and market-related decisions.

The implication to research /policy is that potato has increasingly become a source of cash

income for smallholder farmers (Kaganzi et al., 2009; Devaux et al., 2009). Hence, market

conditions cannot be ignored and, in fact, should be given priority in developing and

disseminating a new technology. Knowledge on the important market-related quality

attributes would help research institutions to develop or introduce new potato varieties with a

19

higher likelihood of adoption. For example, the Michigan potato-breeding program used

quality as an important criterion to develop new potato cultivars (Douches et al. 2001).

The result suggests the need for a bottom-up approach, which seems more feasible these days

than before due to the advent of mobile technology in the rural areas. As indicated in this

study, nearly 7 out of 10 surveyed growers have access to mobile phones. With farmers’ use

of mobile phone technology likely to increase, research centers can make use of the mobile

technology as an alternative model for reaching out a large number of farmers and other

supply chain actors. This reinforces earlier suggestions made by Byerlee et al. (2007) that a

rethinking of the existing technology adoption systems is needed in Ethiopia. So far

information exchange remained top-down with a little room for the local knowledge albeit a

large amount of public money is being spent on research and extension that put Ethiopia

among the largest spenders in Africa (Byerlee et al., 2007).

The problem of quality uncertainty, particularly the oversupply of premature potatoes to the

market, might have brought a change in the organization of the traditional potato supply

chain. Most transactions at the lower end of the chain are governed by a “quasi-vertical” type

of relationship, where the collecting wholesalers are increasingly involved in the harvesting

part of the production cycle. On the other hand, dyadic relationships between downstream

actors at the upper end of the chain remain trust-based, where closer personal ties and

repetitive interaction seem to be more important than formal contracts (see table 19).

Table 19. Relationship between buyers at the central market and collecting wholesalers

Have main supplier (% yes)

Have written contract (% yes)

Total

(N=34)

79.4

11.1

Hotel

(N=11)

81.8

33.3

Stationed

wholesaler (N=10)

60

0

Retailer

(N=13)

92.3

0

6.2.Conclusion

This paper attempts to explain the problem of low adoption for the released potato varieties by

the (ware) potato growers in context of Ethiopia. Farmer based characterisation of the

different potato varieties show that there are quality differences between the released and the

local varieties, particularly with respect to tuber size, stew quality, yield, maturity period, and

disease tolerance. While yield, maturity period, and disease tolerance are considered as the

most important production-related quality characteristics, tuber size and colour remained the

most preferred market-related characteristics.

Preferences for the different quality characteristics were analysed based on the Quality

Assignment Model (QAM) developed by Sloof et al. (1996). Since the model conceptualises

quality based on observable quality characteristics (of perishable products), it nicely fits to the

(Ethiopian) potato supply chain context as the chain is characterised by a large group of

smallholder farmers and traders, where information on unobservable quality characteristics is

hardly conveyed or not considered at all. Accordingly, the released varieties are preferred in

terms of production-related characteristics but the local varieties are more preferred for their

market-related characteristics. In this situation, ware potato growers tend to align their

production in a way to satisfy the quality requirements of downstream actors.

In Ethiopia, formal quality classification is lacking. Hence, supply chain actors use informal

mechanisms such as variety names or production region for information exchange and

continue to involve in the harvesting activities to control potato quality.

20

References

Abadi Ghadim, A. K. and Pannell, D. J. 1999, 'A conceptual framework of adoption of an agricultural

innovation', Agricultural Economics, vol. 21, no. 2, pp 145-154.

Abate, T., Shiferaw, B., Gebeyehu, S., Amsalu, B., Negash, K., Assefa, K., Eshete, M., Aliye, S. and

Hagmann, J. 2011, 'A systems and partnership approach to agricultural research for development:

Lessons from Ethiopia', Outlook on Agriculture, vol. 40, no. 3, pp 213-220.

Beintema, N. and Stads, G. J. 2011, 'African agricultural R&D in the new millennium: Progress for some,

challenges for many', Food Policy Report. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research

Institute.

Belay, K. 2003, 'Constraints to agricultural extension work in Ethiopia: the insiders' view', South African

Journal of Agricultural Extension, vol. 31, no. 1, pp 63-79.

Belay, K. and Abebaw, D. 2004, 'Challenges Facing Agricultural Extension Agents: A Case Study from

South‐western Ethiopia', African Development Review, vol. 16, no. 1, pp 139-168.

Benin, S., Smale, M., Pender, J., 2006, 'Explaining the diversity of cereal crops and varieties grown on

household farms in the highlands of Northern Ethiopia', in Valuing Crop Diversity: On Farm

Genetics Resources and Economic Change, ed M. Smale, CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Biggs, S. D. 1990, 'A multiple source of innovation model of agricultural research and technology

promotion', World Development, vol. 18, no. 11, pp 1481-1499.

Byerlee, D. R., Spielman, D. J., Alemu, D. and Gautam, M. 2007, 'Policies to promote cereal intensification

in Ethiopia: A review of evidence and experience'.

Cavatassi, R., Lipper, L. and Narloch, U. 2011, 'Modern variety adoption and risk management in drought

prone areas: insights from the sorghum farmers of eastern Ethiopia', Agricultural Economics.

Dercon, S. and Christiaensen, L. 2011, 'Consumption risk, technology adoption and poverty traps: evidence

from Ethiopia', Journal of Development Economics, vol. 96, no. 2, pp 159-173.

Devaux, A., Horton, D., Velasco, C., Thiele, G., López, G., Bernet, T., Reinoso, I. and Ordinola, M. 2009,

'Collective action for market chain innovation in the Andes', Food Policy, vol. 34, no. 1, pp 31-38.

Douches, D., Jastrzebski, K., Coombs, J., Chase, R., Hammerschmidt, R. and Kirk, W. 2001, 'Liberator: A

round white chip-processing variety with resistance to scab', American journal of potato research,

vol. 78, no. 6, pp 425-431.

Endale, G., W. Gebremedhin, K. Bekele, and B. Lemaga 2008, 'Potato variety development ', in Root and

tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed G. E. W. Gebremedhin, and B. Lemaga, Ethiopian

Institute of Agricultural Research, Addis Ababa.

ESCS (Ethiopian Smallholders Commercialization Survey). 2005. Unpublished data from a survey

conducted by the Ethiopian Development Research Institute, the Central Statistical Authority, and

the International Food Policy Research Institute. Addis Ababa.

Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research. www.eiar.gov.et. Date of access:15/3/2012.

Feder, G. and Umali, D. L. 1993, 'The adoption of agricultural innovations:: A review', Technological

forecasting and social change, vol. 43, no. 3-4, pp 215-239.

Gebremedhin, W., G. Endale, and B. Lemaga 2008, 'Potato variety development', in Root and tuber crops:

The untapped resources ed G. E. W. Gebremedhin, and B. Lemaga, Ethiopian Institute of

Agricultural Research, Addis Ababa.

Gildemacher, P., Kaguongo, W., Ortiz, O., Tesfaye, A., Woldegiorgis, G., Wagoire, W., Kakuhenzire, R.,

Kinyae, P., Nyongesa, M. and Struik, P. 2009, 'Improving Potato Production in Kenya, Uganda

and Ethiopia: A System Diagnosis', Potato Research, vol. 52, no. 2, pp 173-205.

Hirpa, A., Meuwissen, M. P. M., Tesfaye, A., Lommen, W. J. M., Oude Lansink, A., Tsegaye, A. and

Struik, P. C. 2010, 'Analysis of Seed Potato Systems in Ethiopia', American journal of potato

research, pp 1-16.

Howard, H. 1974, 'Factors influencing the quality of ware potatoes. 1. The genotype', Potato Research, vol.

17, no. 4, pp 490-511.

Jemison Jr, J. M., Sexton, P. and Camire, M. E. 2008, 'Factors influencing consumer preference of fresh

potato varieties in Maine', American journal of potato research, vol. 85, no. 2, pp 140-149.

Kaganzi, E., Ferris, S., Barham, J., Abenakyo, A., Sanginga, P. and Njuki, J. 2009, 'Sustaining linkages to