OS 211 Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211 [A]: Integration, Coordination

![OS 211 Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211 [A]: Integration, Coordination](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007102827_1-16ddcae12e086824a7614c4bf8633097-768x994.png)

OS 211 [A]: Integration, Coordination and Behavior

Lec 21: Dizziness

Dr. Jose Leonardo R. Pascual

TOPIC OUTLINE

I. Introduction of Dizziness

II. Differentials for Dizziness

III. Vestibulo-ocular Reflex (VOR)

IV. Approach to Dizziness

V. Common Dizziness Syndrome

VI. Potentially Life-Threatening Causes of Vertigo

VII. Management of Dizziness

VIII. Summary

Learning Objectives:

1. Be aware of the different meanings of dizziness

2. Differentiate between vertigo versus non-vertiginous dizziness

3. Differentiate between peripheral and central causes of vertigo

4. Know the physical examination techniques to localize vertigo

5. Manage common dizziness disorders cost-effectively

We tried following sir’s flow of the lecture but for some parts, we combined those that we can since sometimes, sir jumped from one topic to another. We also removed those that were not discussed.

I .

INTRODUCTION OF DIZZINESS

“Dizziness covers anything from severe aural vertigo to a housewife feeling nervous in the supermarket.”

– Henry George Miller, 1968

Dizziness is one of the most common complaints bringing patients to your clinic o 5% of walk-in clinic patients o 4% of ER consults

Depending on where you’re thrown, it could be said in different ways: nalulula lilong-lilong lipong ribong-ribong maalindadaw

目眩 xuan yun 眩的

A very subjective complaint and can mean anything to the patient: o headache o light-headedness – floating sensation o vertigo (true dizziness) –spinning sensation o unsteadiness - neurologic, or ataxia

2016: Most causes are benign

Up to 30% of consults for dizziness are due to serious conditions (a.k.a. matter of life and death) such as: o stroke o transient ischemic attacks o cardiac arrhythmias o acute infections o anemia

II. DIFFERENTIALS FOR DIZZINESS

Good history taking entails asking the right questions. o “Does the room spin ?” o “Do you feel unsteady

?” o “Are you feeling lightheaded

?”

BEST QUESTION: “what do you mean by dizzy?”

Don’t ask leading questions and put any words in the patient’s mouth as this may lead to mismanagement.

What do you mean by dizzy?

Table 1. Differential Diagnosis for Dizziness

“I might faint”

“I’m giddy”

“I’m light-headed”

“I might fall”

Syncope/ near syncope

Disequilibrium

Cardiogenic

Neurologic

( Sense of poor equilibrium)

“I’m tilting or rocking”

“The room is spinning”

“I’m just dizzy”

(

True vertigo

Sense of spinning)

Ill-defined

(difficult patient)

Vestibular

Psychogenic/ psychiatric

A. SYNCOPE/ NEAR SYNCOPE

I might faint. I’m giddy. I’m light-headed.

Light-headedness o Feeling of impending loss of consciousness or about to pass out o May be due to a psychological condition ( anxiety or stress )

Gienah, AJ, Irene

1

December 9, 2013 o Patient may report to you some form of palpitation which confirms an anxious state or a cardiac condition o Ask yourself the right questions like what are the possible things that could cause light headedness?

Low blood pressure

Low blood sugar

Tilt Table Test

– test the cardiologist may order to confirm lightheadedness o Patient is tilt in varying degrees to see what elevation will cause light-headedness o Confirms the presence of light headedness that is due to a cardiac condition

Figure 1. Tilt Table Test

Overall, etiology points to a cardiovascular problem (Orthostatic hypotention, cardiac arrythmia, hypersensitive carotid sinus, vasodepressor spells/ vasovagal syncope, valvular or subvalvular aortic stenosis) or any form of strain like coughing, anything that could diminish blood flow to the brain, arrhythmia, medications, hyperventilation which induce vasoconstriction in the brain, hypoglycemia

Differential Diagnoses of Light-Headedness

Systemic Disorders

Cardiovascular presyncope o hypovolemia o postural hypotension o vasovagal o carotid sinus o postmicturition o posttussive o vasodilators o ANS dysfunction o Addison’s disease o brady/tachyarrhytmias o heart block o congestive heart failure o valvular heart disease

Medications

Hyperventilation

COPD

Infection

Hypoglycemia

Hyperglycemia o anemia o alcohol o street drugs

Ophthalmological disorders o glaucoma o lens implant o refractive errors o new prescription lenses o acute ocular muscle paralysis

B. DYSEQUILIBRIUM

I might fall.

Subjective feeling of pseudodrunkenness or unsure footing when walking/ambulating

Non-vestibular neurologic disorder / brain problem

Patients who complaint that they might fall, some form of imbalance

This can be due to anything outside the inner ear or the vestibular apparatus o Headache, migraine, sinusitis, post-traumatic concussion, seizure, degenerative disorders, peripheral disorders like diabetes, paraneoplastic cerebellar syndrome

Differential Diagnoses of Disequilibrium

Headache o sinus o muscle contraction

Complex partial seizures

Dementia

Peripheral neuropathy

Page 1 / 9

o migraine

Concussion (due to trauma)

Paraneoplastic cerebellar dysfunction

C. ILL-DEFINED LIGHT-HEADEDNESS

I’m just dizzy.

“Spacey” or “disconnected” dizziness without any feeling of motion or loss of balance

Patients who cannot describe what they mean by dizzy

Psychiatric mainly anxiety states

Differential Diagnoses of Ill-Defined Light-Headedness

Anxiety

Panic attacks

Depression

Psychogenic seizure (or even pseudo-seizure)

Conversion reaction

Malingering

D. TRUE VERTIGO

I’m tilting or rocking. The room is spinning.

Defined as a false sense of motion , either of self or the surroundings

Vestibular problem which can be central or peripheral o Peripheral

– anything outside the CNS beginning from the nucleus of CN VIII all the way to its peripheral nerve into the inner ear

ENT further subcategorize as cochlear or retrocochlear

Cochlear – lesion in the inner ear & labyrinth

Retrocochlear – lesion in CN VIII

Figure 2. Classification of

True Vertigo

Worsened by motion

Represents either physiologic stimulation or pathologic dysfunction in any of the 3 systems subserving spatial orientation and posture: the vestibular system , visual system , or somatosensory system

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

Can be due to some form of middle ear problems like perforated ear drums later becoming granulomas eating the mastoid process

Can even have a stroke in the inner ear because the labyrinthine artery is a branch of AICA

Can be due to any problem that interfere with the electrolytes (mainly potassium) of the inner ear like

As a rule, consider peripheral vestibulopathy (cochlear lesions) in all episodes of vertigo NOT accompanied by neurologic symptoms

CN VI is important in peripheral vertigo because it is controlled by CN

VIII

Causes of Peripheral Vertigo

Middle ear lesions o Infections

Viral

Bacterial o Otosclerosis o Cholesteatomas o Tumors

Glomus tympanicum/jugulare

Squamous cell CA

Inner ear lesions (most common) o Benign positional vertigo* o Vestibular neuronitis* o Ménière’s disease* o Labyrinthitis

Infection or autoimmune o Vascular disorders

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency

Hemorrhage (rare)

Labyrinthine artery

Bleeding diathesis o Systemic disorders

Diabetes

Uremia o Trauma

Perilymph fistula o Ototoxins

Alcohol

Salicylates

Anti-epileptics

Aminoglycosides

Loop diuretics

Cinchona alkaloids (quinidine, quinine)

Heavy metals (cisplatin)

Retrocochlear

(CN VIII) lesions o Infection o Collagen vascular disease o Tumor

Schwannom a

Neurofibrom a

Meningioma

Metastasis

(Rare)

Figure 4. Big Circle (CNS) : vestibular nuclei, cerebellum, vestibulospinal tract, MLF, cranial nerve 3, 4, 6, cerebral cortex. Small

Circle (PNS) : ear, labyrinth, cranial nerve 8

Central Vertigo

Simply any disconnections in the central pathways involved in balance and spatial orientation

The central vestibular system includes the EOM cranial nerves , cerebellum and vestibular nuclei o EOM cranial nerves ensure that the visual image that falls on the retina remains focused, regardless of head position (vestibuloocular reflex) o Supranuclear connection from the cerebellum integrates signal o Vestibular nuclei are found in the medulla and acts on muscles to control posture

Figure 3. The Vestibular Apparatus

Peripheral Vertigo

Involve the nerve (CNVIII up to its nucleus in the brainstem)

Gienah, AJ, Irene Page 2 / 9

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

Figure 7. Recall: Supranuclear connection from the cerebellum integrates signal. Vestibular nuclei are found in the medulla and acts on muscles to control posture.

VOR or Doll’s Eye Reflex

Doll’s Eye Sign

A test used to evaluate a patient’s VOR (especially a patient in coma)

Complex partial seizures

Demyelinating diseases o Multiple sclerosis

Trauma

Hereditary disorders o Friedreich’s ataxia o Refsum’s diseas e atrophy

Figure 5. The Central Vestibular Systems

Causes of Central Vertigo

Metabolic disorders o Alcohol cerebellar degeneration

Infection o Meningitis o Encephalitis

Developmental disorders o Malformations of the inner ear o Craniocervial junction malformation o Arnold-Chiari malformation

Downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum, with concomitant hydrocephalus o O l ivopontocerebellar

III. VESTIBULO-OCULAR REFLEX (VOR)

A. INTRODUCTION

Figure 4 . Testing for Doll’s Eye Sign

PROCEDURE

1) Hold the patient’s upper eyelids open.

2) Quickly turn his head from side-to-side and note eye movements with each turn.

RESULTS

(+) patient’s eyes move to the opposite direction

( –) patient’s eyes remain fixed in midposition

The absence of this reflex means there is something wrong with the verstibular apparatus applicable to both peripheral and central vertigo

B. HOW IT WORKS

For example when turning your head to the right , the movement causes perilymph in the R horizontal semicircular canal to move to the left, causing hair cells to detect movement. turning head to the R activates R horizontal SC turning head to the L activates L horizontal

SC

Figure 6. Recall: Cranial Nerves to the EOM ensure that the visual image that falls on the retina remains focused, regardless of head position (VOR)

Gienah, AJ, Irene

Signals are sent via R vestibular nerve (CN VIII) to the R vestibular nuclei in the medulla.

The R vestibular nucleus (CN VIII) activates the L abducens nucleus (CN VI)

The L abducens nerve (CN VI) activates the lateral rectus of the L eye.

The R oculomotor nerve (CN III) is yoked by the MLF to the abducens nerve (CN VI).

Another nerve tract projects also from the L abducens nucleus by the medial longitudinal fasciculus to the R oculomotor nuclei , activating the medial rectus of the R eye .

Both eyes look to the left.

Page 3 / 9

Figure 8. VOR events when the head is turned to the right.

Turning your head to the right while your head is bent backward

R posterior canal is activated

Eyes look down and to the left

Turning your head to the right

R horizontal canal is activated

Eyes look to the left

Turning your head to right while your head is bent forward

R superior canal is activated

Eyes look up and to the left

Table 2 and Figure 9. Activation of the various semi-circular canals

Figure 10. Endolymph movement stimulates hair cells to detect direction of head movement

What happens when we move our heads? o The vestibular apparatus and nerve tells us where our head is going o The eyes drift as a result of stimulation of the contralateral

CN VI ( slow component ) o The contralateral frontal eye field quickly returns the eyes to midline position ( fast component = “ saccade ”)

Gienah, AJ, Irene

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211 o But the accuracy of returning eyes to the midline is controlled by the cerebellum

C. CEREBELLUM

Role of cerebellum: o Adjust your arms and legs to maintain steady upright position o Adjust your eyeballs to where you are in space.

IV. APPROACH TO DIZZINESS

Demonstration: Val pushes Mike .

Mike assumes the anti-gravity posture (elbows and knees bent, one leg forward) so he won’t tumble down.

This also demonstrates how the anti-gravity muscles – thighs, shoulders and trunk are important in upright posture.

Trying to be steady will be harder with eyes closed because the eyeballs will tell one where he is in space.

A. STEP 1: VERTIGINOUS OR NON- VERTIGIOUS

Is it vertiginous or non-vertiginous dizziness?

A good history can elucidate what exactly is the etiology of the patient’s dizziness.

Table 3. Vertiginous vs. Non-vertiginous Dizziness

Vertigo o sense of rotation of either the patient or his environment o sense of imbalance/disequilibrium in the head

(not the feet)

Unsteadiness due to

Cerebellar/

Proprioception

Deficits

Non-Vertiginous

Dizziness o ataxia/ sense of imbalance in the limbs or body o posterior column or cerebellar problem

Vague Dizziness o feeling of impending loss of consciousness (presyncope) o “light-headedness”, “fear of falling”, “swimming sensation” o psychological, emotional disturbance

Table 4. Differentiating Vestibular and Nonvestibular Dizzines

s

Property

Description

Time Course episodic or constant

Associated

Symptoms

Predisposing

Factors

Precipitating

Factors

Vestibular Dizziness spinning, whirling, rotating, off-balance nausea, vomiting pallor diaphoresis hearing loss, tinnitus congenital inner ear anomaly ototoxins ear surgery

Any head/body position changes ear infection or trauma

Nonvestibular

Dizziness light-headed, faint, dazed, floating episodic or constant paresthesias palpitations headache syncope syncope due to CVS disease psychiatric illness body position changes stress, fear, anxiety

hyperventilation

B. STEP 2: CENTRAL OR PERIPHERAL VERTIGO

Peripheral vs. Central Vertigo

There are several clues in the history that point to peripheral vertigo versus central vertigo o History of ear discharge or infection o Hearing loss and tinnitus o Intake of ototoxic medication o Sudden onset (e.g., due to stroke) o Absence of neurologic deficits

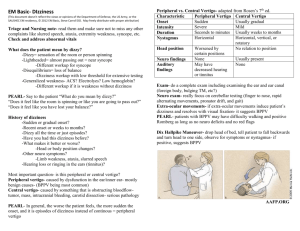

Table 5. Differentiating Peripheral and Central Dizziness.

Peripheral Vertigo Central Vertigo

Onset

Quality

Intensity

Occurrence

Duration sudden spinning, rotating severe episodic seconds, minutes, insidious disequilibrium mild to moderate constant weeks or longer

Page 4 / 9

hours, days

Exacerbation by

Head Movement

Nausea & Vomiting

Imbalance

Ear Pressure/Pain

Hearing Loss moderate to severe severe mild occasional frequent

Tinnitus frequent

Neurologic

Symptoms rare

*Central Vertigo – symptoms of imbalance mild mild moderate

None rare rare frequent

Differentiating Central from Peripheral Vertigo: Ototoxic

Examination

Check the ears. If there is a problem in the ears (e.g. perforation or swelling of the eardrums), it usually indicates a vestibular or peripheral origin

Differentiating Central from Peripheral Vertigo: Focused Neurologic

Examination

Watch out for deterioration of sensorium o CNS infection o Space-occupying lesions (brain tumors) o Encephalopathies (toxic /metabolic)

A. CRANIAL NERVE EXAMINATION

Possible findings o Anisocoria (pupils of different size) , papilledema (swollen, indicates high intracranial pressure)

Make sure to check pupils and perform a fundoscopy o Vertical diplopia

Indicates a lesion in the brainstem; a red flag!

Can be an interruption of MLF o Abnormalities of smooth pursuit

Tested by instructing the patient to follow your fingers with his eyes

Indicates a lesion in the cerebellum o Dysmetria of saccadic eye movements (overshooting of fingers or eyes) o Pathologic nystagmus (lesion in the cerebellum, brainstem) o Sluggish corneal reflex o Facial paralysis o Hearing loss/lateralization CN VIII

Indicates an ear problem o Impaired gag reflex o Tongue deviation

B. MOTOR EXAMINATION

Possible findings o Tremors o Carpopedal spasm after hyperventilation and turning pale

Young individuals may have carpopedal spasms (toes & fingers stiffen, become cupped) due to nervousness such that it looks like they’re going to pass out

Muscle atrophy

Muscle fasciculations

Hypotonia

C. CEREBELLAR TESTTING

Possible findings o Limb ataxia o Truncal ataxia o Gait ataxia o Remember to ask the patient to sit up/get up from bed and walk, even if they’re dizzy. You can’t check for ataxia if the patient is lying down.

D. SENSORY EXAMINATION

Possible findings o Impaired proprioception o Perioral numbness (hyperventilating patients) o Glove and stocking paresthesias

suggestive of peripheral neuropathy (diabetes)

o Romberg’s Test

Differentiates between a proprioceptive vs a cerebellar cause of imbalance

E. DEEP TENDON REFLEXES

Possible findings

(1) Hyporeflexia

(2) Hyperreflexia

(3) Pendular reflexes – swaying back and forth due to cerebellar problem

Gienah, AJ, Irene

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

ROMBERG’S TEST

PROCEDURE

RESULTS

1) Ask patient to stand, with feet together and arms apart.

2) Eyes are open initially.

3) Ask patient to close eyes.

(+) falls with eyes closed (dorsal column problem)

You don’t say negative RT, just say: does not fall with eyes closed

Falls with eyes open (cerebellar)

If vision is taken away and patient loses balance, it means that there is a vestibular disorder or a proprioceptive disorder

Basis of this test is balance involves a combination of proprioception, vestibular input, and vision; if any 2 of these systems are working, the person should be able to demonstrate a fair degree of balance

(+) Romberg indicates a dorsal column problem.

Differentiating Central from Peripheral Vertigo: Spescial Maneuvers

To Test the Labyrinth

A. HEAD SHAKING – test for vestibular problem

Ask patient to shake his head, as in saying “no”, for

PROCEDURE

20 seconds.

-Check for nystagmus- slow phase moves toward the side of the unilateral peripheral lesion.

RESULTS

(+) falling, marked intensification of dizziness because the vestibular apparatus is overwhelmed

( –) no change

Figure 11. Frenzel Lenses. Patient can wear Frenzel lenses which are high diopter lenses that prevent fixation, allowing vestibular nystagmus to be seen clearly and to separate him from the environment Magnifies the eyes

B. RAPID IMPULSE TEST

Also called the head thrust test or passive head movement test

Used to test for ocular instability

Among the most reliable bedside tests for labyrinthine function

PROCEDURE

1) Ask patient to relax first, then fixate on a target.

2) Explain the need to relax the neck muscles while remaining focused on the target.

3) Examiner quickly rotates the patient’s head by 10°.

4) Observe patient’s eyes for slippage from target with quick saccadic correction.

NORMAL eyes remain on target

RESULTS

ABNORMAL slippage with quick saccadic motion

Page 5 / 9

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

MECHANISM OF DIX-HALPIKE

Dix-Hallpike maneuver (change from position A to position B) triggers the movement of the otolith into the more slender lumen (like a roller coaster) leading to

BPPV nystagmus.

Figure 12. Rapid Impulse Test.

A & B: Normal finding. The patient’s eyes stay fixated on the target even with head rotation.

C, D, & E: There is a R-sided lesion. The eyes remain in midposition with quick saccadic correction (by frontal eye fields and cerebellum)

Ocular instability is elicited when head is turned toward the side of the peripheral lesion o The eyes overshoot towards the side of the lesion. It does not move to the other side to stay fixated on the object. o Then the frontal eye fields and cerebellum compensate to bring eyes back to direction of the target causing saccades .

C. DIX- HALPIKE MANEUVER

A diagnostic maneuver used to identify Benign Paroxysmal

Positioning Vertigo (BPPV)

History and a (+) Dix-Hallpike are sufficient to make a diagnosis of

BPPV (no need for further tests or imaging studies).

MECHANISM OF VERTIGO IN DPPV

Figure 13. Dix-Hallpike Maneuver.

PROCEDURE

RESULTS

1)

Patient’s head is rotated 45° sitting down.

2) Quickly move the patient from the sitting position to the supine position with the head tilted 30 °-40° over the end of the table. Maintain this position for

30s with patient’s eyes open to see if eyeballs have nystagmus.

3) Rapidly bring up the patient to the sitting position.

4) Repeat the procedure with the patient’s head rotated 45° to the left side, then again rotated 45° to the right side.

(+) nystagmus

( –) no nystagmus

Rule of Thumb: 30 seconds (not shorter, because this is the time when the patient will say that they are dizzy)

After a latency of few seconds the patient develops sudden vertigo.

Dysfunctional ear is the one that is downward when vertigo occurs.

Rotatory torsional nystagmus: the fast component moves away from the affected ear (ear is firing unnecessarily).

Duration of vertigo and nystagmus: 30-40 seconds , usually less than

15 seconds.

Changing from supine to sitting position reverses the direction of vertigo and nystagmus.

Changes in position confirms labyrinthine involvement (this is already a confirmatory test for benign positional vertigo ; no need for MRI)

Jerking is caused by the frontal eye field.

Repeated maneuvers may no longer result in vertigo and nystagmus

(“ fatigue

”).

Gienah, AJ, Irene

Figure 13. Mechanism of R Horizontal SCC Lithiasis.

small arrows – direction of otolith movement large arrows

– direction of deviation of the cupula o Pathology: otolith breaks off. It will move downward and will give a sensation of movement when there wasn’t any. o Usually in the lateral semicircular canals (SCC)

Unilateral stimulation of SCC by movement of otoliths when there is no head movement -> an exaggerated response without a stimulus (mind is tricked, you feel like you are turning around even if you’re just stationary)

D. CALORIC MANEUVER

Tests for diminished labyrinthine response to thermally-induced nystagmus on the affected side

Involves alternate irrigation of the external auditory canals by cold

H

2

O followed by warm H

2

O

Checks if labyrinths are functional or not by inducing change in temperature of fluid in the inner ear

A test for comatose patients. Brain dead patients will have no response.

Figure 14. Caloric Testing.

Page 6 / 9

PROCEDURE

RESULTS

1) The patient’s he a d is tilted forward 30 ° above the horizontal so that the horizontal SCC assumes a more vertical position.

2) Irrigation first with cold water (7 ° below body temperature) for 30s.

3) After 5 min, irrigation with warm water (7

° above body temperature) for 30s.

NORMAL eyeball deviation

ABNORMAL no eyeball deviation

Cold Water

Warm Water

Fast phase of nystagmus to the side opposite from the cold water filled ear

Fast phase of nystagmus to the same side as the warm water filled ear

Absence of response will indicate the paretic side

“

COWS

” (

Cold Opposite , Warm Same )

E. OTHER ELABORATE MANEUVERS

1 . Barany Chair: Used in NASA to prepare astronauts for zero gravity environment; also for anti-vertigo treatment

2. Unterberget Test – to assess whether a patient has vestibular pathology, not useful for central disorders of balance

PROCEDURE Patient is asked to walk on spot with eyes closed.

NORMAL no rotation

RESULTS

ABNORMAL rotation to side of labyrinthine lesion

3. Fukuda Test – diagnosis of vertigo-associated disease

PROCEDURE 1) Ask patient to march in place.

RESULTS

NORMAL no rotation

ABNORMAL 10-

20° angle deviation to the L or R

V. COMMON DIZZINESS SYNDROME

A. BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONING VERTIGO

Also simply called benign positional vertigo.

The most common cause of vertigo in clinical practice

The usual onset is middle age

Brief periods of vertigo induced by position changes of the head; vertigo is precipitated by certain events (e.g. rolling over in bed, getting in or out of bed, bending over, extending the neck)

Vertigo typically lasts a few seconds, always less than one minute

Pathophysiology

Caused by dislodgement of CaCO

3

crystals from the otolithic membrane in the utricle o Cupulolithiasis

Settling on the cupula o Canalolithiasis

Free floating in the membranous portion of the posterior SCC

Figure 15. Positions of Crystals in BPPV.

Diagnosis

Based on history and supported by a (+) Dix-Hallpike test

Torsional rotatory nystagmus with fast component toward the affected ear when it is placed downward

Treatment

Most patients’ symptoms resolve without treatment (1/3 - 2/3 of patients) within a week to a month o During period of illness, can be very distressing to the patient o Symptoms recur in more than half of patients

Vestibular Suppressants o Do not prevent vertigo o Long-term use of these medications is discouraged

Gienah, AJ, Irene

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

Vestibular Rehabilitation Exercises

Canalith Repositioning Maneuvers o Has showed improvement rates of 67-89%

Semont Maneuver o Performed 3x a row, 3x a day (morning, noon, and night) o Most patients become free of symptoms after doing this for 3 days

Figure 16. Semont Maneuver.

PROCEDURE

1) The patient initially in a sitting position, with his head turned 45

° to the side of the unaffected ear.

2) The patient is laid on the side of the affected ear, with head still turned. The position is maintained for about a minute. o Induces movement of the particle in the

SC by gravity, leading to rotatory nystagmus toward the lower ear that extinguishes after a brief interval

3) With the head still in the same place, patient is rapidly swung over to the side of the unaffected ear, so that the nose now points downward. This position is maintained for about a minute. o Particle in SC now moves toward the exit from the canal

4) The patient returns slowly to sitting position. o Particle settles in utricular space, where it can no longer induce rotatory vertigo

Surgery o Rare patients who fail to respond to vestibular rehabilitation or canalith repositioning are candidates o Done only if the correct ear and correct semicircular canal has been identified (usually the posterior SC)

Mechanical Occlusion

Division of the Singular Nerve

Division of the inferior vestibular nerve that supplies the posterior SC

Disconnect the SC from its nerve supply

B. PHOBIC POSTURAL VERTIGO

Also called non-otogenic dizziness and psychogenic dizziness

Second most common cause of vertigo

Attacks are precipitated or exacerbated by stressors, which can be typical situations (e.g. crowds, empty spaces, driving)

Patient’s personality is usually of an obsessive-compulsive or reactive-depressive type

At the onset of the disorder, there’s a vestibular disturbance (25%) or a stress ful situation (70%)

Clinical Features

Postural vertigo with unsteadiness of stance and gait

Neurologic exam and ancillary tests are generally unremarkable

Fluctuating unsteadiness of stance and gait with attacks of fear of falling, but without an actual fall

Anxiety and autonomic disturbances during or after the attacks

Increasingly severe avoidance behaviour is common

Page 7 / 9

Treatment

A thorough diagnostic assessment to allay the patient’s fear of having a serious organic disease

– tell patient that there is really nothing wrong with them

Psycho-educative therapy to inform the patient of the pathologic mechanism and the precipitating factors and situations

Desensitization by self-exposure (i.e. deliberately seeking out situations that precipitate vertigo, e.g. riding roller coasters)

Light sporting activity or consumption of a small amount of alcohol can also improve symptoms

If symptoms persist, pharmacotherapy, e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and/or cognitive behavioral therapy

Treatment markedly improves symptoms in about 70% of patients

C. MENIERE’S DISEASE

Impaired drainage of endolymph due to lymphatic channel dilation leading to accumulation of endolymph inside the SCC

Attacks usually last <24 hours

Cause is usually idiopathic, but may be due to trauma, ear surgery, or ear infections

NORMAL EAR

MÉNIÈRE'S DISEASE

EAR

Figure 17. Build-

Up of Endolymph in Ménière’s Disease.

Clinical Features

Triad of inner ear pathology: episodes of dizziness , tinnitus , and hearing loss

Sensation of fullness in the ear

Temporary hearing loss and distorted hearing during attacks

“Drop attacks” = sudden vertigo leading to falls

Histopathology

Distension of endolymphatic system

Episodic ruptures the of endolymph into perilymph

K + in endolymph damages hair cells in the organ of Corti, leading to hearing loss

Cause is usually idiopathic, but may occur after trauma, ear surgey, or ear infection

Figure 18. Distension of the

Semicircular Canals in Ménière’s

Disease.

Treatment

Management is empirical: antiemetics and vestibular suppressants

Patient is maintained on low salt diet and diuretics

May lead to deafness if untreated

D. VESTIBULAR NEURITIS

A diagnosis of exclusion or a wastebasket diagnosis

Symptoms usually peak within 24 hours

Patient lies relatively immobile because movement worsens the symptoms

Symptoms will subside in several days, up to 3 months, until the patient’s vestibular system compensates

Gienah, AJ, Irene

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

Clinical Features

Figure 19. Vestibular Neuronitis.

Sudden severe vertigo with nausea/vomiting in the absence of auditory symptoms

Absence of hearing impairment/tinnitus

Absence of neurologic deficits

Vertigo with spontaneous nystagmus , with fast component beating away from involved ear (usually unilateral)

Treatment

Short-term use of antihistamines / anticholinergics

Anti-emetics

Benzodiazepines (if necessary, for sedation)

Corticosteroids (if started early, shorten duration of the disease)

Avoid prolonged immobility

Vestibular rehabilitation

Low salt diet and diuretics

VI. POTENTIALLY LIFE-THREATENING CAUSES OF VERTIGO

T Percentage of dangerous diagnoses increases as age increases, with the highest percentage (about 25%) in patients

≥75 years old

(+) neurologic deficits or the 5Ds (dizziness, dysphagia, dystaxia, diplopia, dysarthria)

A. CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASE

5 Ds: Dizziness, diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, dystaxia

May result from the following: o Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery Infarction (AICA)

Supplies the brainstem and labyrinth, so presents with inability to hear in one ear o Posterior Inferior cerebellar Artery Infarction (PICA)

Supplies the medulla o Cerebellar Hemisphere Infarcts o Cerebellar Hemorrhage

By compressing the 4 th ventricle, you get hydrocephalus which may cause hernia

B. BACTERIAL LABYRINTHITIS

Life-threatening if not promptly treated with antibiotics

Acute purulent infection of the labyrinth, usually an extension from chronic mastoiditis

Bilateral cases may occur with bacterial meningitis

VII. MANAGEMENT OF DIZZINESS

Stabilize the patient

Rule out the most life-threatening diagnosis (5D’s) and manage accordingly

Depending on the localization, refer to a neurologist/otorhinolaryngologist/cardiologist/psychiatrist

Guided by history and PE, perform diagnostics (but you don’t need to s pend money on these) o Routine work-ups (CBC, blood chemistries; R/O SLE) o Cardiac enzymes, 12-lead ECG (R/O cardiac problems) o Arterial blood gases, pulse oximetry, CXR (R/O metabolic problems) o Imaging of the skull and brain (CT/MRI) if you think there’s a structural problem of the inner ear, middle ear, or the brain

Therapeutics o Reassure the patient o Semi-prone, lie on the side to avoid aspiration of vomitus o Supplemental O

2

via nasal cannula, if necessary o Insert IV line only when they need fluid resuscitation o Vestibular suppressants :

Page 8 / 9

Antihistamines – reduces motion sickness, also have anticholinergic activity, only those which cross the blood brain barrier are useful

Meclizine 25 mg tab PO q8

– q12 hours

Dipenhydramine 25-50 mg tab PO q6 hours

Anticholinergics - only for prevention, not for cure

Scopolamine 0.5mg transdermal patch q3-q4 days (behind ear)

Histamine (H3) agonists

Betahistine 8mg-32mg TID

Increase blood circulation to the labyrinth

Considered as placebo by US FDA o Anti-emetics

– if necessary

Promethazine 25-50 mg PO/PR q6 hours o Anxiolytics and antidepressants

If warranted, try to avoid these because they induce dependence

Diazepam 2mg tab PO q8-q12 hours

Clonazepam 2mg 0.5mg tab PO q12 o

Vestibular rehabilitation

VIII. SUMMARY

Allow the dizzy patient to explain how he feels in his own words

Determine if your patient has vertigo vs. non-vertigo

Localize the vertigo o Is it in the ear or CNS? o Is it in the labyrinth, vestibular nerve, or brainstem?

Stabilize the patient

Treat the vertigo and the nausea/vomiting

Reassure the patient and refer (e.g. to ORL)

END OF TRANSCRIPTION

G: Hello 2017 (Reign Supreme!)! Hello transmates! Hello researchmates, clingy, anatomates. Hey hey , Phivestar, Extradyizz,

Ampliphi! Hello buddy Martin! Watch and download the soundtrack of

Frozen and watch Wicked next year. Chuck Palahniuk has a new book

(Doomed) grab a copy! Also, merry merry Christmas and happy happy

2014 in advance! :D

Lecture 21: Dizziness OS 211

“Choose your battles wisely. After all, life isn't measured by how many times you stood up to fight. It's not winning battles that makes you happy, but it's how many times you turned away and chose to look into a better direction. Life is too short to spend it on warring. Fight only the most, most, most important ones, let the rest go.” –C. JoyBell C.

A: MER RY CHRISTMAS CLASS 2017! Let’s not forget the real reason for the season!

I: Last trans before Christmas vacation! Huling tumbling na lang! To the people na kasama ko nung Friday, you guys are deeply appreciated!

Labyu powz!!! :D

Gienah, AJ, Irene Page 9 / 9