- Stepnex Services

Contract Number:

Contractor Name:

USAID Technical Office:

Date of Report:

Document Title:

Author’s Name:

SOW Title and Work Plan Action:

Contract Number ?

Chemonics International, Inc.

Office of Economic Opportunities

USAID Pakistan

September

Ian Auldist

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Livestock Policy Framework

USAID Pakistan FIRMS Project

Provincial Livestock Policy Framework

Work Plan Level 33550 Action #6435, SOW #1901

The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States

Agency for International Development, the United States Government or Chemonics

International Inc.

Data Page

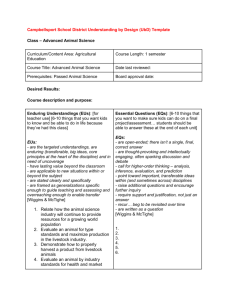

Name of Component: Business Enabling Environment (BEE)

Author’s Name: Ian H. Auldist

Key words: Animal welfare, breed improvement, dairy, disease surveillance, extension, livestock, markets, meat processing, quality assurance, policy,

Abstract

Current livestock policies in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are analyzed, and impacts and distortions identified. Based on survey data and stakeholder analysis specific policy impacts are assessed, and effects on livestock markets and meat processing identified. A policy framework is presented using principles drawn from international best practice, which provides a basis for public sector institutional reform, and increased participation and efficiency of the private sector.

Abbreviations and Local Terms

ACIAR

ADB

ADHIS

AI

AMPC

APVMA

AQIS

ASEAN

Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research

Asian Development Bank

Australian Dairy Herd Improvement Scheme

Artificial insemination

Australian Meat Processor Corporation

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority

Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service

Association of South East Asian Nations

CCPP

DAGRIS

EU

FAO

FMD

GDP

Ha

Halal

Contagious Caprine Pleuropneumonia

Domestic Animals Genetic Resources Information System

European Union

Food and Agriculture Organisation

Foot and Mouth Disease

Gross domestic product

Hectare

Islamic Law permissible food designation

JAKIM Department of Islamic Development Malaysia

KPK Khyber Pakhtunkhua

L&DD Dept Livestock and Dairy Development Department

LOG

Mandi

MLA

MTDF

Local Government Ordinance

Marketplace

Meat and Livestock Australia

Mid Term Development Framework

NAREEAB National Agricultural Research and Extension Advisory Board

NGO Non Government Organisation

NVD

NWFP

National Vendor Declaration

North West Frontier Province

PPR Peste des Petits Ruminants

PROGEBE Regional Project on Sustainable Management of Endemic Ruminant Livestock

Rs

RSPCA

Rupees

Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

TMA

UNDP

USAID

UVAS

Tehsil Municipal Administration

United Nations Development Programme

United States Agency for International Development

University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences

Table of Contents

SectionI. Introduction

Section II Methodologyfor KPK Policy Development

2

Section III KPK policy background

1. Livestock industry context

2. Provincial government livestock functions

3. Policy reflected in budget priorities

4.Current livestock industry policies

5. Genetic improvement and indigenous breed conservation

6. Disease surveillance and treatment

7. Extension and capacity building

8. Research and development

9. Animal welfare

10. Livestock feed

12.Existing policy reviews

11. Rangeland management and pastoralism

Section IV International livestock policy models

1. Disease surveillance and prevention

2. Disease treatment

3. Vaccine production

5. Extension services

4. Feed production and monitoring

6. Breed conservation and improvement

7. Research and development

8. Livestock marketing

9. Meat processing and marketing

10.Government farms

11. Animal welfare

12. Rangeland management

Section V Policy principles based on international practice

Section VI. Proposed policy reforms for key areas of livestock sector

Section VII. Policy framework

References

Appendices list

10

12

30

30

31

31

29

29

29

30

32

33

33

34

35

16

23

24

25

13

13

14

16

25

25

26

26

28

37

39

44

60

61

Executive Summary

Livestock industry potential in KPK is constrained by distortions and imbalances in the policy and regulatory framework which have created inefficiencies in the planning, management and development of livestock infrastructure, facilities and services. The private sector is also affected by restrictions from entering areas of business dominated by government, such as livestock market management, and slaughter and processing for domestic consumption, limiting incentive to develop markets, create demand, and increase economic activity. Although there is potential for increased growth, demonstrated by the increase in dairy and meat price indices over the last ten years, the current policy environment has helped to reduce economic performance to a level which is unacceptable under the current conditions of demand. In this context the extension service also fails to meet the needs of producers, who supply markets where demand is limited by current policies and lack of quality assurance.

In response to this situation a range ofinternational policy models weredraw on to establish principles on which to base a new policy framework. These principles are as follows:

Elimination of market distortions through restriction on competition

Creation of a demand-driven approach to markets

Recognition that there is a cost for goods and services

Elimination of resource allocation distortions through public ownership of business entities

Representation for stakeholders in industry decisions

Industry self-regulation

Independence of regulatory bodies

Sustainable use of resources

Independent policy for social and economic disadvantage

Recognition of cultural attitudes

Using these principles policy recommendations were made for a number of key areas of livestock policy. These recommendations are listed as follows:

1. Disease surveillance and prevention

Surveillance and epidemiological analysis to be a core responsibility of government.

Institutional surveillance data collection to include mainstream industry sources such aslivestock markets and slaughterhouses.

Facilitation of private sector producers to provide routine information to government regarding disease incidence.

A specific agency at provincial level to address disease prevention issues

Interim need for a mechanism to provide prevention and control services to specific disadvantaged areas of the industry including subsistence producers.

2. Disease treatment

The public sector to maintain the responsibility for disease epidemic control

An independent body to undertake livestock medicine registration and labelling, to ensure that users including producers and private veterinarians comply with safe use, dosage rates, and with-holding periods, and provincial government to regulate through incentives and penalties to ensure compliance with labelling protocols.

A regulatory framework to include dispute resolution and accountability of veterinarians.

KPK government to maintain support for subsistence producers in disease treatment and control by providing training, availability of quality medicines, and a sustainable mechanism for delivering community livestock health services.

3. Vaccine production

Review of vaccine needs, identifying demand and assessing ability of industry sectors to pay

Facilitation of private sector entry through licensing, where commercially viable, vaccines to be imported or produced by the private sector while essential non-commercial vaccine production to be supported by the public sector.

An independent body and regulatory framework responsible for vaccine registration, standards and enforcement.

KPK Government vaccine production to be limited to essential non-profitable production.

4. Feed production and monitoring

Facilitation of trade in non-manufactured feeds/forage

An independent feed test laboratory to provide objective quality analysis, and use it as a basis for developing improved livestock nutrition

KPK Government to develop the capacity to establish a quality assurance process with vendor declaration procedures for non-manufactured feeds.

5. Extension services

Legislate mechanisms to enable funding of extension from industry contributions.

KPK Government to develop livestock production extension services, improving delivery through out-sourcing, and facilitating capacity development of private extension providers.

KPK Government to develop mechanisms to deliver extension services to subsistence production sector.

6. Breed improvement

Review cost-benefits to industry of current public breed improvement programs.

Regulate and develop standards for private semen production and imported and traded semen, and provide technical support for commercial breed development organisations.

Develop protocols for preservation of indigenous breeds.

KPK Government to support growth of a viable private sector breeding industry with appropriate breed standards.

7. Research and development

Research to be managed by an independent body which assesses and prioritizes projects, and links funding donors with stakeholders.

The independent coordinating body to have representation from government, funding agencies and industry end-users

Research agencies to compete for funding.

8. Livestock marketing

Legislate to enable competition from the private sector to hold livestock markets, with redefinition of the roles of various operators, and coordination by an independent regulatory entity, representing the major stake holders.

KPK government to establish market practices and standards, market information collection and distribution, and collection of levies from market participants to fund market development, infrastructure and facilities.

The private sector to operate markets within the KPK regulatory framework; markets to be economically sustainable based on fee for services.

9. Meat processing

Legislate to enable competition from the private sector to undertake domestic meat processing.

Repeal meat price regulation, and legislation which prohibits slaughter of useful animals and institutes meatless days.

Establish an independent body to provide accreditation for slaughter and processing facilities and ensure compliance with developed standards in all licensed processing plants.

10 Government and private farm management

Review all government participation in commercial livestock production, in terms of current function, and activities for the public good, determining criteria and standards for operation

Develop guidelines for future involvement in public/private partnerships and joint ventures.

Facilitate industry representation mechanisms to enable effective consultation and industry advice to government.

11. Animal welfare

Involve the community in assembling a code of practice for animal welfare in markets, slaughter, transport, research, and commercial production, including nutrition and management of farm animals

KPK government to facilitate and coordinate compliance with the code of practice by a selected animal welfare body.

Enlist animal welfare organizations to monitor and report neglect and cruelty.

12. Environmental protection

Set standards and regulate to ensure no negative effects on the environment as a result of livestock management, transport, marketing or processing, or disposal of waste associated with activities such as feedlots and intensive livestock industries.

Develop the capacity of the KPK Environment Department to undertake regulation and compliance activities.

13. Rangeland management

Support traditional grazing practices and management of rangelands by traditional grazing communities.

Establish management entities or Rangeland Development Advisory Bodies which include the widest range of stakeholders, including grazing community representatives, and

Forestry and Livestock Departments.

Establish practical and cost-effective ecological monitoring systems, including all nonforest wastelands and public grazing areas in monitoring and management planning.

Support livelihood interventions for traditional grazing communities, for example in the preparation and marketing of wool and hair products.

Where possible charge users with management costs.

Section I. Introduction

Livestock are important toPakistan’seconomy, with the sector’s total assets estimated to be worth more than US $19 billion. Contributing approximately 12% to the GDP 1 and more than 50% of value-added in agriculture 2 , livestock products (valued at Rs 165 billion) are assuming an increasing share of agricultural output, rising from 25% in 1996 to 52% in 2011-12.The estimated annual growth in the livestock sector of 3.7% 3 is mainly attributed to increasing value of livestock products. Dairy products contribute 75% to the total value of the sector, and a world dairy indicator price rise of 125% which occurred during the decade is background to the continued strong domestic demand for dairy products. Growthhas also been associated with developing markets.

Although world meat price rises of 86% over the past ten years have flattened since 2011, 4 meat exports from Pakistan are increasing. Export value ofmeat of US$123 millionin 2111-2012was up

14%on the previous year 5 , followed by a further 41% rise in the first seven months of 2012-

2103 6 .This trend follows India’s dominance of export beef markets since 2011 with mainly buffalo product.

7

Culturally KPKProvince is strongly associated with livestock production, as meat and milk are staple food items, andmore than 70% of families own ruminant livestock.

Rangelandoccupying46% of total land area dominates as the basis for production. Landless producers and traditional subsistence systems with informal marketing arrangements contribute to the status of KPK as the province with the highest poverty rating (39.2% rated poor compared to nationally 34.0%).As production becomes less dependent on rangeland grazing, and more on integrated crop-livestock systems, satisfying local and international demand will require increased efficiency, and transfer of resources from existing agricultural enterprises.So far modern largerscale systems have had limited impact on production, for example only 9% of buffaloes are managed on a commercial scale. Due to the high level of informal marketing and processing the contribution of livestock tothe KPK economy is difficult to measure, with one estimate 8 suggestingapproximately Rs 75 billion worth of livestock products per year, which is 30% by value 9 of the total KPK agriculture GDP.

With enterprise margins regarded as below potential in much of the industry, livestock is still treated as a sub-sector of agriculture. This potential is constrained by distortions and imbalances in the policy and regulatory framework which have created inefficiencies in the planning, management and development of livestock infrastructure, facilities and services. The private sector is also affected by restrictions from entering areas of business dominated by government, such as livestock market management, and slaughter and processing for domestic consumption, limiting incentive to develop markets, create demand, and increase economic activity. Although there is potential for increased growth, demonstrated by the increase in dairy and meat price indices over the last ten years, the current policy environment has helped to reduce economic performance to a level which is unacceptable under these conditions of demand. The extension service also fails to meet the needs of producers, who supply markets where demand is limited by current policies and lack of quality assurance.

1 ADB Report: National Agriculture Sector Strategy 2008

2

Pakistan Economic Survey 2011-12

3

Govt of Pakistan Planning Commission Report: Framework for Economic Growth 2011

4

FAO Meat Price Index

5

Business Recorder 6/6/2012

6

“The Nation” 25/5/2013

7

FAO Dairy Price Index

8

Prof M. Subhan Qureshi, Pakissan 29/4/2013

9

KPK Comprehensive Development Strategy 2010-2017

In this context the industry demands a framework which will redefine the role of government, and that of private sector stakeholders. This will allow stakeholders currently lacking the capacity to optimize the productivity and profitability of livestock to take advantage of existing demand, generate more economic activity, and use resources more rationally.

A policy reviewto create such a framework is important in the setting ofadditional responsibilities for provincial government as a result of the Eighteenth Constitutional Amendment in June 2011, which devolved most of the subjects in the Concurrent List, transferring the power to legislate on these subjects to the provinces. With the Provincial Legislature able to adopt, amend or repeal federal laws on these subjects, the fate of some existing laws, for example involving prevention of transfer of livestock diseases between Provinces, has become uncertain. The amendment also gave

Provinces the authority to directly deal with donors and to borrow from international financing agencies such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

To meet these challenges, the Government of KPK in 2013 asked FIRMS Project of USAID for assistance with policy development. This followed reviews in 2011 of livestock policies for the governments of Punjab, Sindh and Baluchistan and development ofpolicy frameworks based on international best-practice. Frameworks with long and short-term policy optionswere accepted by

Punjab, wheretwonew draft laws are currently being reviewed. Sindh and Balochistan have also accepted the policy principles developed with FIRMS Project, and are proceeding in the policy reviewprocess.

Section II. Methodology for KPK policy development

The FIRMS Project,with a background in policy development, hasanalytical capacity and valuable networks in each province. Added to experience working with governments, FIRMS Project is strategically positioned to understand provincial issues, and to use that experienceto achieve constructive outcomes.To take advantage of this intra-provincial learning FIRMS Project has deployed the same procedurewith KPK as that usedfor policy reviews in the other provinces. The same FIRMS team was mobilized, and as in the other provinces it was regarded as essential to have a thorough understanding of industry functionto enable identification of crucial factors limitingpolicy effectiveness.

The team included an Australian livestock policy specialist with experience in a number of countries as well as Pakistan, a legal specialist, Dr Dil Mohammad, to reviewthe general legal framework and legal instruments, and local expertise with capacity to survey and report on key areas.Background data relating to existing policy was assembled, and research initiated into important policy constraints for the industry. Trading and processing of the animals which form the main industry asset were seen as key areas where data was needed to understand policy breakdown. The experienced research team used to investigate the Punjab and Sindh livestock markets was deployed in KPK, with the object of analyzing market function and its relation to policy. In addition the team addressed the functioning and limitations of the slaughtering and processing sector.

Research was also undertaken to achieve an appreciation of the roles and responsibilities of sector participants, including those of provincial government leaders from KPK. Stakeholders interviewed included government officers at a range of levels, technical specialists, producers and producer organization representatives, female livestock professionals, environmental interest groups, and development program managers.

10 Data from these sources was complemented by specific L&DD Department policy and strategy statements, provincial economic reviews, and specialist evaluations of relevant issues.

Specific tasks in the consultant’s Scope of Work are listed as an appendix: 11

10Appendix 2 Record of Meetings and Interviews

11Appendix 1 FIRMS Project Consultancy Scope of Work

Section III KPK policy background

1.Livestock industry context

The industry is based on livestock populations which are poorly documented because of informal slaughter practices, unrecorded movements across international and provincial borders, a high degree of mobility associated with nomadic or transhumant grazing practices, and absence of data collection associated with industry facilities such as markets and slaughterhouses.As a result there is poor knowledge and documentation of parameters such as reproductive efficiency, turnoff, and mortality, which are essential for developing policy which addresses industry constraints and advances performance.

Table 1 KPK livestock population trends

1960

1972 12

1976

1986

1996

2006 13

2012 14

1960-2012% increase

1996-2006 % increase/year

2006-2012 % increase/year

Cattle

Buffaloes Sheep Goats Total

3.20 million 0.65 million 2.43 million 5.03 million 11.31million

2.96

3.00

3.28

4.24

5.97

7.43

132%

4.08%

3.28%

0.79

0.76

1.27

1.39

1.93

2.29

252%

3.82%

2.63%

2.45

3.67

1.60

2.82

3.36

3.60

48%

1.92%

1.1%

3.74

4.69

2.90

6.76

9.60

11.24

123%

4.19%

2.43

9.94

12.12

9.05

15.21

20.86

24.56

117%

3.71%

2.96%

2006-2012 increase/year

243,000 60,000 40,000 273,000 616,000

There is also limited data regarding animal flows in and out of KPK. The analysis by Shahid and

Arqum 15 in 2010 estimated that 682,550 buffaloes, 485,450 cattle, 57,670 sheep, and 37,960 goats enter KPK from Punjab per year. Dry buffaloes and young cattle predominate, followed by pregnant buffaloes destined for dairy production. Their estimate of animals which are legally exported live from KPKwas 25,000 per year 16 . In comparison an industryassessment of total animals illegally exported from Pakistan is 2.5 million 17 , with a large proportion assumed to leave from KPK. However most of the animals illegally exported from KPK to Afghanistan are understood to originate from Punjab 18 . Formal slaughter activities account for possibly 800,000 animals,but due to lack of data regarding the flow of KPK sheep and goats supplying Punjab markets,and lack of informal slaughter and illegal live export numbers,an accurate model of industry dynamics is difficult to construct.

12

TRTA II “Enhancing Livestock Sector Competitiveness”

13

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

14

KPK L&DD Dept pers. Com. 2013

15

Shahid and Arqum (2010)

16

Shahid and Arqum (2010)

17

PAMCO quoted Shahram Haq Express Tribune 28 th A

18

KPK L&DD Dept, pers.com 2013

To construct a balance sheet, estimates of natural increase are difficult. Using the Census data in

Table 2, and assuming that there is a significant slaughter of cattle and buffaloes between birth and three years of age,it can be estimated that the total annual natural increase from breeding lies somewhere between 5.04 and 9.05 million animals. The turnoff, or number of animals slaughtered or exported from KPK, taking into account mortality, inflows and population increase would also approach this figure.

Table 2: KPK livestock breeding performance

Total number at census

Cattle 5.96

Buffaloes 1.93

Sheep 3.36

Goats 9.60

Total 20.85

2006

(millions)

Breeding

Females

Natural increase if reproduction rate is 80%

3.04 >3 years 2.43

1.09 >3 years 0.87

1.64 >1 year 1.31

5.55 >1 year 4.44

11.32 9.05

Total male and female animals below breeding age

3.07<1 years

6.85

Approx. actual natural increase(and est. reproduction rate)

1.97 <3 years 0.65 (21%)

0.74 <3 years 0.25 (22%)

1.07 <1years 1.07 (65%)

3.07 (55%)

5.04

The above discussion highlights the lack of reliable data for planning. One definite conclusion is that livestock numbers have more than doubled over the past twenty years, and animal populations continue to increase, although the rate of increase has fallen slightly. Thesustained cattle increases of more than 240,000 per year, and sheep and goats of more than 310,000 per year obviously have impacts on resources, particularly the environment, onlivestock disease, marketing and valueadding industries, and on government service needs.

2.Provincial government livestock functions

The Livestock and Dairy Development Directorate, which is part of the Agriculture Department, lists its functions on its website as follows:

Provision of animal health facilities and services to livestock farmers through curative and prophylactic measures; establishment and maintenance of veterinary hospitals, dispensaries and centers in functional order.

Improvement of local breeds of cattle and buffalo through the provision of artificial insemination service to the livestock farmers; establishment and maintenance of artificial insemination centers and sub-centers.

Provision of livestock production extension services to the livestock farmers (and female farmers in selected cluster areas) through a network of veterinary institutions.

Provision of periodical in-service training to the departmental staff in animal husbandry, extension and animal health disciplines; practical pre-service training to Veterinary

Assistant students of Agricultural Training Institute (ATI), Peshawar; training to field staff, male and female livestock farmers for various NGOs and projects in livestock management and related subjects.

Establishment of livestock breeding farms for propagation of improved breeds of different livestock species, wherever feasible.

Improvement of poultry production through the establishment of demonstration- cum-egg

production farms.

Provision of services to Local Government Department in the meat inspection by

conducting ante-mortem and post-mortem examination of animals.

Undertaking livestock development related activities in collaboration with donor assisted area development projects and NGOs

The animal health and extension services are the same, delivered through 218 centres. The livestock breeding farms consist of Harichand farm for cattle, D.I.Khan for buffalo, and Jaba

Livestock Research Station for sheep. There is one government poultry farm at Peshawar. Meat inspection services are provided at 13 local government slaughterhouses. There is currently one

NGO assisted, the Sarhad Rural Support Program.

The Veterinary Research Institute lists its duties as:

Control of Poultry and Livestock diseases of economic and zoonotic importance.

Enhancement of Livestock Productivity per unit targeted at poverty alleviation, women development and improvement in human diet.

Assistance to the Universities in Academic Research.

Human Resource Development for generating self-employment and capacity building for establishing commercial enterprises.

Cooperation with Wildlife, Health and other Departments in areas of common interest

The L&DD Department has also responsibility for implementing specific projects including:

1. Preservation of indigenous breeds (Achai cow project).

2. Pastoralism unit.

3. Pastoral development projects: Burawei-Haripur and Mahodand-Khadokhei .

4. Disaster (flood) recovery.

Apart from flood recovery, these are recently-funded projects, initiated in response to government policy direction.

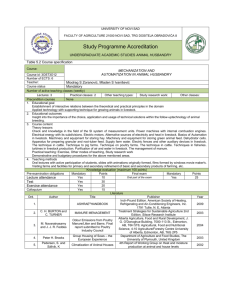

3.Policy assumptionsfrom budget indicators

Livestock policy prioritization is reflected in the delegation of funds towards particular activities.

This is summarized in Table 2 which lists the available figures for delegation of provincial funds towards Livestock Department activities.

Table 3: Livestock share of Annual Development Program budget

2008-9 ADP 2011-12

ADP

2012-13 ADP

Agriculture allocation (Rs million)

Agric. share of total ADP

715

1.7%

1355

1.6%

1470

1.5%

Livestock allocation (Rs million) 217 670 380

Livestock share of Agriculture ADP 30% 45% 26%

19

Taking into account the lack of a Development Program in 2009-10, there has been a downward trend in livestock’s share of the budget, despite the livestock industry’s strong potential for growth.

Funding detail has reflected policy attention to specific areas. In the 2011-12 ProgramLivestock extension received Rs 240million for ongoing and new schemes,which included the Achai cattle conservation and development project which started in 2009 with a requirement for Rs 222 million and was allocated in 2011 Rs 42 million. It also included a livelihood program for gender-based interventions intended to provide female livestock owners with training, animals and better communication,which was allocated Rs25 million.Small ruminants were a focus, through a goat and sheep research centre in Swat with Rs 70 million allocated to improving local goat species through crossing with high-quality foreign species, a project for preservation and development of local sheep in Hazara and Malakand costing Rs 25 million, and establishment of Barani research institutes for goat and sheep.

In the allocations for 2012-13 the most significant new itemout of the Rs 380 million was the allocation of Rs 150 million towards establishment of a Pastoralism Unit, with the aim of conservation and support for traditional transhumant livestock production systems. The other significant allocation indicated attention to ways of supporting small the transition of farmers into business entities, through theMeat and Dairy Development withMarket Linkages project which was allocated Rs30 million.

4.Current livestockindustry policies

4.1 Meat industry

4.1.1 Livestock markets

FIRMS commissioned in 2013 a Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal to provide a detailed study of

KPK slaughter houses and markets, and their operation.

20 KPK livestock markets cater for a series of live animal flows which service industry trade and slaughter needs. There are no large terminal markets (see Table 3) as in Punjab, there are only primary collection and secondary distribution markets. For example these enable traders to purchase sheep and goats to transport from KPK to

Punjab to meet demand for mutton. Old buffaloes transported from Punjab are also available in

19

KPK Planning and Development Department Annual Development programs

20

Appendix 1: Shahzad Saftar, KPK Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal

secondary markets in KPK to meet demand for low-priced beef and the illegal live trade to

Afghanistan. Younger cattle also flow in to meet demand for slaughter and export of beef to

Afghanistan..

Table 4 Livestock Market Characteristics 21

Type of Market Main Sellers Main Buyers Purpose of Purchase

Primary markets collection

Secondary distribution markets

Producers/traders

Producers/traders

Other producers For stock replacement or fattening

Local butchers

Traders

Slaughtering for retail selling of meat

For resale in larger markets

Other producers/ farmers For stock replacement or fattening

Local butchers Slaughter

Terminal markets Traders

Traders/buying agents

Local houses/butchers slaughter

Traders/exporters

Dairy farmers

For resale in terminal markets/supply to processors, dairy farmers and exporters

Slaughter for local supply as well as for export

For supply to different buyers/export

For dairy farms

KPK livestock markets have been controlled exclusively by Local Government, under West

Pakistan Municipal Committees (Cattle Market) Rules 1969.The subject was so exclusively vested in the Local Government, under Local Government Ordinance 2001, that the Provincial

Government had no role; and its authority did not extend to cattle markets. This defect has been removed, with the 2001 ordinance replaced by the KPK Local Government Act, 2012, which allows the Provincial Government to frame rules in all matters and empowers it to control the making of by-laws by the local government. 22

Table 5: Livestock markets administered by Local Government in KPK

S # District Number of Livestock Location/ Schedule

Markets

1.

Abbotabad

2.

Bannu

3.

Buner

1

2

3

Havalian (Wednesday)

Bannu (Friday), Kakki(Wednesday)

Swari (Saturday), Nagri (Tuesda)y, Budhal (Wednesday)

4.

Charsadda

5.

D.I.Khan

3

6

6.

Haripur

7.

Karak

8.

Kohat

9.

Lakki

10.

Malakand

11.

Mansehra

12.

Mardan

13.

Nowshera

14.

Peshawar

15.

Swabi

16.

Swat

1

5

3

4

1

3

2

1

7

4

2

Utmanzai (Tuesday), Charsadda (Wednesday), Shabqadar (Friday)

Ramak (Friday), Browa (Wednesday), D.I.Khan (Friday), Paharpur (Sunday),

Daraban Kalan (Friday), Kulachi (Monday)

Near District Council, Haripur (Thursday)

Takhtte Nasratti (Saturday), Ahmad Abad (Friday), Mayanki Banda

(Monday), Karak City (Sunday), Latambar (Wednesday)

Near Kohat Stand (Sunday), Lacchi (Friday), Bili Tang (Sunday)

Khudad Khel (Sunday), Sarai Naurang (Thursday), Fezu (Tuesday), Tajori

(Tuesday)

Dargai Bazaar (Sunday)

Mansehra (Monday), Shinkiari (Saturday), Garri Habibullah (Sunday)

Mardan (Saturday), Shabaz Gari (Sunday)

Main Road near Kabul River (Wednesday)

Sarband (Thursday), Nasir Pur (Saturday, Monday), Badabher (Saturday),

Palosai (Friday), Warsak Road (Tuesday), Ringroad (Saturday, Wednesday),

Naguman (Monday)

Swabi (Thursday), Karnal Sher kalli (Saturday), Tordher (Tuesday), Topi

(Wednesday)

Aman Kot (Thursday), Matta (Wednesday)

21

Appendix : Shahzad Saftar, KPK Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal

22

Preliminary KPK Legal Report: Dr Dil Mohammad

Source:- Livestock and Dairy Development Department, Peshawar, KPK.

This control has in the past enabled Local Governments to generate considerable revenue, by selling the rights to market management to private contractors, who have the right to charge market users. Although under LGO 2001 there is allowance for private livestock markets, in practice

Local Government has a monopoly, and as a result there is no competition from private entities to lower costs or provide better services.

Table 6: KPK livestock market charges 23

Sr. # Livestock Market

1. Bakra Mandi, Main

Road Near Kabul

River, Nowshera

(Public market)

2.

3.

Nasir Pur, Peshawar

(Private Market)

Havelian,

Abbottabad

(Public market)

Type of animals

Traded

Sheep and Goat

Large animals -

Buffalo and cattle

Large and small animals

Charges on Entry

(Rs.)

From producer

Rs. 20/animal.

From trader

Rs. 15/animal

From producers or trader carrying one or two animals

Rs. 100/animal

From other Traders

Rs. 500/load of 10 animals

Rs. 10/animal from every one for each type of animal

Charges on Transaction (Rs.)

From producers

7-10% of value

From Traders

Rs. 100-700/animal

From seller

Rs. 200/animal

From Trader buyer

Rs. 500-700/load of 8 animals and from buyer buying 1 or 2 animals Rs. 200-300/animal

Producer buyer 7% for all types of animals.

Traders/butchers pay Rs. 250-300/animal for sheep & goat and 7% for all types of large animals

4. Mardan

(Public market)

Large and small animals

Rs. 10/animal from every one for each type of animal

5. Aman

Mingora, Swat

Kot,

(Public market)

Large and small animals

Rs. 20/animal from every one for each type of animal

Producer buyers pay 7-10% per animal

Trader buyers pay Rs. 150-250/small and Rs.

600-700/large animal.

Producers buyers pay 10% of value while traders/butchers pay Rs. 150-170/small and

Rs. 600-650/large animal

The Terms and Conditions of the market contract include details the value of contract, payment schedule and schedule of charges which the contractor may charge.The survey of KPK markets provides some idea of the potential to generate income from a market. As detailed in Table 4 there are two types of market charges: entry and transaction. Entry charges may be Rs 10-20 per small animal, and Rs 100-200 for large. Transaction charges are variable, rarely publicly listed, and in some markets range between 5% and 7% of transaction value, in others a flat rate of Rs 300-700.

Traders are charged a discounted rate.

In return for these charges, Local Governments offers little in the way of facilities, as there are no guidelines or standards for housing, feeding, shade and water availability, truck loading ramps, or disease prevention through quarantine facilities. There are no standards for regulating and operating markets to meet the needs of vendors in the market, and a number of barriers inhibit the transparency and free flow of information necessary to remove market distortions. For example there are no facilities to allow weighing of animals, and there are no standard rules for transactions, which are conducted in secret and encourage collusive practices. Provincial veterinary officers do not provide any services, any certification of disease-free status to buyers, or collect information relating to diseases. No other record of any type is collected regarding number and type of animals traded, sources of supply, or destination, all valuable data for planning and industry development.

There is little coordination or organization between producers and vendors, other than sharing transport costs to reduce the cost of market participation. If livestock producers and vendors instead use informal markets to avoid conditions and charges they are operating illegally. Producers are handicapped by ignorance of prices and livestock weights and values, whereas traders and brokers have well-organized networks, knowledge of prices, and receive discounted market charges.

23

Appendix 1: Shahzad Saftar, KPK Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal

4.1.2 Domestic slaughterand meat marketing

The domestic slaughtering of animals is regulated by the Slaughter Control Act 1963, which prohibits the slaughter of livestock termed as useful animals (female animals within specified age or those which are pregnant or fit for breeding), slaughter outside municipal slaughterhouses, or slaughter on the meatless days of Tuesday and Wednesday. The operation of municipal slaughterhouseshas historically been controlled by bye-laws of the respective local governments under Local Government Ordinance 2001, providing the regulation for issues such as standards and revenue collection. The KPK Provincial government however has recently acquired the power to control the making of bye-laws by local government, under the Local Government Act

2012.

24 The scale of legal domestic slaughter is indicated in Table 5, based on the most recent available government data.

Table7: Animals slaughtered in Local Government Slaughterhouses in KPK 25

Cattle

Buffaloes

Sheep

Goats

2005-6

199 thousand

181

161

175

2006-7

219 thousand

201

180

195

2007-8

228 thousand

211

194

204

Total 716 796 835

Based on this data legal slaughter would provide only approximately 8 kg of meat per head of population per year, suggesting that the meat industry isalso supplied by a high level of informal slaughter occurring outside Municipal slaughterhouses. Survey results from the FIRMScommissioned Rapid Livestock Market Survey showed that Municipal slaughterhouses are mainly located to provide facilities for domestic slaughter in urban areas (Table 6). In rural and remote areas there is generally informal slaughter,a feature associated with subsistence livestock production, and as only eleven out of twenty-five KPK districts have municipal slaughterhouses 26 it is assumed that in the other fourteen districts informal slaughter is the normal practice.

A useful estimate of informal slaughter is difficult to obtain due to live animal movement in and out of KPK. A possible turnoff figure for KPK of 1.2 million can beestimatedon the basis of 24 million total KPK animals, one third adult females, and a turnoff rate of 15%,(typical for low reproductive rates and mature age of slaughter animals).

Table 8: Slaughterhouses in KPK

S# District Location of legal Slaughter Houses Public or Private

1.

Abbotabad

2.

Bannu

3.

Charsadda

4.

,,

5.

D.I.Khan

6.

Haripur

7.

Kohat

8.

Mansehra

9.

Mardan

10.

,,

11.

Peshawar

12.

,,

Abbotabad City

Bannu City

Shabqadar, Tangi

Tangi

Mufti Mehmood Eye Hospital

Near Sabzi Mandi, Haripur

Peshawar Chowk, Kohat City

Mansehra City main Chowk

Mardan,

Takht Bhai

TMA

,,

,,

,,

,,

,,

,,

,,

Haji Asghar Slaughter House, Ring Rd Private

Munir Meat Co Ring Rd

,,

,,

,,

24

Appendix: Dil Mohammad report

25

KPK Bureau of Statistics website 2011quoting L&DD data

26

Appendix 1: Shahzad Saftar, KPK Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal

13.

,,

14.

,,

15.

,,

16.

Swat

Hamza Halal Foods, Najoi Buduli Rd ,,

Euro Foods, Industrial Estate ,,

Charsadda Road

Saidu Sharif near Grassy Ground

17.

Swabi Near Badri Pull Swabi

Source:- Livestock and Dairy Development Department, KPK.

TMA

,,

,,

The Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal detailed the operation and policy implications of representative slaughterhouses in KPK. Obviously the frequency of informal slaughter indicates that the legal requirement to conform to slaughter in a Municipal facility is not widely enforced, and penalties are nominal. Legal slaughter may provide butchers with pre-slaughter inspection by a qualified inspector, andstamping of the carcase. This service is supplied by arrangement with

L&DD Department, but the conditions are not transparent, and field survey indicated little inspection being undertaken. Normally L&DD Department charges Local Government for this service,which is a part-time duty of veterinary staff.

Local government revenue collection to provide legal slaughtertypically consists of Rs 25 for small and Rs 50 for large animals slaughtered by independent butchers, or Rs 50 for small and Rs 150 for large animals slaughtered by a permanent team of slaughterers. Most of throughput consists of sheep and goats of all ages, and aged buffaloes are 90% of large animals, consistent with the law forbidding slaughter of useful animals. Fees are collected by Municipal Corporation staff or a contractor, and also other fees where possible such as for parking.

Atypical Municipal slaughterhouse has minimal facilities, consisting of little more than a roof, and water when electricity is available. There are with no cooling pens for animals, and rarely large animal restraining facilities to enable Halal slaughter, or large animal hanging equipment for removal of viscera or movement of carcases. There is no refrigeration, by-products utilization, or waste management systems.There are no hygiene standards in place, and limited inspections by qualified veterinarians with uncertain protocols and standards, and limited disease surveillance or condemnation of sick animals. Each TMA has its own priorities, so there are no consistent standards. The Local Governments collects substantial slaughter fees, with few costs, and without opportunity for any legal competition from the private sector. This discourages any opportunity for investment in the industry, which might bring more efficient systems, producing meat of higher quality. In addition the butchers in the meat processing industry are not equipped with the proper knowledge to maintain purpose-built slaughterhouses or ensure hygiene and quality control in slaughtering and inspection of meat.

27

Retail meat quality and price isregulated by Local Government, on behalf of the KPK Food

Department 28 . Under the 1977 Price Control and Prevention of Profiteering and Hoarding Act

District Price Review Committees regularly review and set meat prices, in a process unrelated to costs of production, meat quality or consumer demand, and without consistency between

Districts.Although meat prices are reported to have risen by 40% between 2010 and 2012 29 , as meat supply is increasing at a rate of 1.8%, while demand is increasing at 5-6%, effects of price control are slaughter of diseased animals to achieve profit margins.Inconsistent enforcement may allow some high-quality meat to be available at higher prices.

The KPK Health Department is also involved in the function of retail meat inspection and assurance.All departments involved view the current policy as unwieldy, as it 30 creates distortions

27

Trade-Related Technical Assistance Program. (2012) “Enhancing Livestock Sector Export Competitiveness”

28

KPK Food Department website 2013

29

Trade-Related Technical Assistance Program. (2012) “Enhancing Livestock Sector Export Competitiveness”

30

KPK Food Department website 2013

and inefficiencies in the market. The policy affects competition in the supply chain, limiting price rewards for quality, and ensuring that butchers use low-quality product to cut costs.

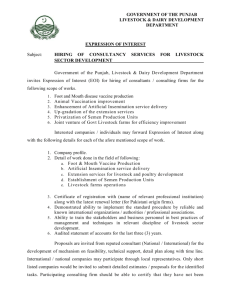

4.1.3 Export slaughter and marketing

Export slaughter and meat processing is a major component of the meat industry in KPK, which falls under Federal Government regulation. Slaughterhouses in KPK must be registered with the

Animal Quarantine Department of the Livestock Wing of the Ministry of National Food Security and Research.

31 Three private processors in KPK produce meat under these conditions for export to Afghanistan 32 . Slaughter facilities are basic with covered killing areas and blast chillers, and cold stores which are dependent on electricity supply. Most of this meat is processed from younger cattle of 160-200 kg liveweight, and fills an essential food supply role for Afghanistan. The business process varies from direct export by the owner of the slaughterhouse to contract slaughter for others. Typical costs for this are Rs 70 for entry by the animal owner, and Rs 27-30 per kg by the Afghan buyer of the meat. The actual meat sale price may be approximately Rs 275 per kg.

Transport to Afghanistan is byrefrigerated intermodal containers (known as “reefers”) with 16 tons capacity, owned by the slaughterhouses, at a cost of about Rs 50,000 per trip.

No apparent measures are taken to check for livestock diseases at the private slaughterhouses.

Although no food safety assurance systems were observed during the rapid survey, the quality certification process occurson demand of the meat buyers, and is believed to be undertaken by private sector veterinarians engaged by the Quarantine Department.Export of meat to Afghanistan is also facilitated in other ways by the Department, such as smoothing financial transactions with

Afghan purchasing entities.

33 Although private meat exporters are on record claiming export is constrained by taxes, interference from provincial departments, and lack of a clear policy 34 this was not observed.

4.1.4.Export of live animals

Illegal transport of live animalsfrom KPK over borders into Afghanistan in response tohigh prices is a livestock policy issue. This is in the context of traditional movement of flocks and herds across the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, and unfilled demand for meat within Afghanistan. Media analyses have condemned smuggling as the reason for rising meat prices 35 in KPK. With the total illegal flow out of Pakistan estimated at 2.5 million animals per year, 36 debate over the impact of cattle exports on domestic pricesincludes suggestions that policies associated with food security limiting legal export may encouragesmuggling.

Current policy is to prevent, through the use of roadblocks, live animals being transported over the national border without permits. Under the Constitution the Federal Government is responsible, and since the 18 th Amendment, the Ministry of Food Security and Research has created a

“Livestock Wing” with a redefined mandate which includes accountability for regulation of import and export of livestock and livestock products. Federal permits are issued for legal export, but these permits then are traded, possibly a number of times, after which transporters with permits illegally export more than permitted. Provincial implementation of policy in KPK has been transferred between L&DD Department, Food Department 37 , and Home and Tribal Affairs

Department, as movement of animals over Federal Agency boundaries is part of the issue. As freedom of cattle movement into Afghanistan reduces profits from illegal smuggling, managing

31

Ministry of National Food Security and Research websit 2011

32

Appendix 1: Shahzad Saftar, KPK Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal

3333

Regulatory Procedures for Export of Livestock and Livestock Products from Pakistan 2009 SMEDA

34

CEO Anis Associates quoted “The Express Tribune” 28/4/13

35

“Nation” 22/10/2012 High court orders KP Government to stop smuggling

36

Punjab Agriculture and Meat Company (2013)

37

KPK Food Department website

and restricting movement of cattle is now current policy, and responsibility has returned to L&DD

Department.

4.2. Dairy Industry

A livestock industry policy assumption has been that cattle and buffaloes are kept primarily for milk production, with beef as a secondary enterprise consideration. This is changing as meat demand and prices rise in relation to milk prices, although slaughter of buffalo calves at a young age continues to be a common practice. Cattle numbers continue to rise faster than buffalo numbers, reflecting some change in dairy production systems, partly associated with introduction of exotic dairy cattle genetics.

In a dairy industry dominated by small-holders the public or private sector has not made any significant investment in milk collection or preservation systems, chilling tanks, or milk processing plants. 38 This is because demand is for fresh milk, and not for the higher-priced less desirable

UHT milk, which is available from Punjab in the marketplace. Value-chain development for milk involving pasteurization is not policy for public or private entities, although it is regarded as the preferred compromise between scale of operation, treatment effectiveness, and consumer satisfaction.

Small-holders are dependent ontraditional supply chains to service consumers, sometimes organized into producer groups based around chilling centres. An example of programs designed to make them more productive elements of the industry is the L&DD Department supported (from

2005) innovative initiative “Milk Packaging in Central and Southern Districts of NWFP”, which adopted a bottom-up approach to develop the province’s dairy industry through cooperation between the public and private sectors. The project created groups of small-holders and marketing channels, with activities including technical and management support services, training particularly of women, and milk collection units. However policy associated with dairy valuechain development depends on projects financing units, and is let down by constraints such as transport and electricity.

Commercial dairy production enterprises in KPK are stated to be a victim of the cost-price squeeze 39 caused by rising input prices and fixed product prices. Fertilizer prices are claimed to have risen by 150% over five years to 2012 40 at the same time as food inflation has seenmilk price rises of little more than 20%.As with meat Local Government is empowered to set prices for milk, on behalf of the Food and Health Departments, andDistrict Price Review Committees impose milk prices in the retail market without reference to cost of production or demand in the retail market.The price is fixed as the maximum retail price, but in fact it serves as the minimum retail price,because consumers, although aware of official prices, are understood to pay a higher price to buy good quality milk 41 .

Regulation of quality of dairy products is the responsibility of Local Government, but as the Pure

Food Ordinance 1960 does not apply to these food items, implementation at grassroots level is extremely limited.

42

4.3 Fibre Industry

38

Umm E. Zia Pakistan: A dairy sector at a crossroads FAO 2009

39

Hafizur Rehman, Sarhad Dairy Farmers Association, (2004) Pakistan Press Association Service

40

M. Akbar 2012 Global Food Security website

41

Appendix 1: Shahzad Saftar, KPK Livestock Rapid Market Appraisal

42

Umm E. Zia Pakistan: A dairy sector at a crossroads FAO 2009

Wool and hair marketing is regulated under the Agricultural Produce (Grading and Marketing) Act

1937.Wool which enters the marketing chain may be graded according to the standards established under the Wool Grading and Marketing Rules (1953), at the major wool market centres which are in Punjab and Sindh. Termed Pakmark grades these differentiate between Pak Super, which applies to KPK breeds such as Kaghani, Hashtnagri and Michni (fibre diameters less than 40 microns),

Pak Medium, and Pak Coarse typified by the Bulkhi breed (fibre diameters greater than 45 microns). Indigenous goat breeds such as Damani and Kaghani also produce significant quantities of marketable hair.

Grading may be undertaken locally by traders who deal in wool and hair produced as a universal product of livestock in small-holder and transhumant/nomadic pastoral systems. As a product of traditional cultural importance and value, wool has the potential to become a greater contributor to pastoral incomes. However with the main processing capacity in Multan and Karachi this industry is unlikely to provide livelihood opportunities for pastoralists without further assistance in preparation and marketing coordination. Better shearing techniques, and washing and grading of wool from local breeds by producers does not appear to have been considered, as successfully introduced across the border in Balochistan.

43

Historically KPK government and donor agencies have invested substantially in the industry, for example through FAO and other agency investment in the Jaba Sheep Farm at Mansehra responsible for development and distribution of breeding stock with higher quality wool from the imported Rambouillet breed. However the availability of cheap high quality Australian and New

Zealand wool in the nineties limited industry development, with the result that only three wool processing units are currently listed in KPK.

5.Genetic improvement and indigenous breed conservation

Genetic improvement of livestock breeds is a clearly-statedobjective of government policy, as set out in the L&DD Department Rules of Business. Dairy breed improvement is through a network of 310 AI centres, and semen is producedfrom Harichand centre for cattle and buffalo. In a typical year 268,000 cows were inseminated at a cost of Rs 30 per year per cow. This is a supply-driven program, with annual targets set for each District. Although a major government budget item there is no evidence of any cost-benefit reviews, existing guidelines or standards for semen or breeding animals distributed, or any progeny-testing of sires used for semen production.Private enterprise also imports and distributes dairy genetics in KPK; in 2012 318,768 semen doses were imported into Pakistan, also 4300 embryos and 9500 live animals 44 , all focused on dairy production. The federal Ministry of National Food Security and Research Livestock Wing is responsible for quality standards for this imported genetic material.

Recently there has also been pressure for KPK government to establish a policy regarding the rapidly-eroding numbers and loss of genetic purity of indigenous breeds. These are regarded as future genetic resources, not only for Pakistan but for the wider livestock industry. In low-input situations,where there is disease incidence, harsh climate or poor nutrition they may have production and survival advantages over exotic crossbreeds. Breeds which have been recommended for conservation includeAchai cattle, Azikhali buffalo, Gabrali cattle from Swat and

Kohistan, Bishgali cattle and Kari sheep from Chitral, and Ajari goats. Conservation policies are consequently regarded as urgent to preserve the genetic diversity. There are a number of requirements if conservation is to be effective including phenotypic and genotypic characterization, zone-wise breeding strategies, establishment of conservation centres at appropriate sites, and promotional activities. KPK L&DD Department has undertaken to implement a conservation program for Achai cattle. Action has included registration of Achai cattle

43

USAID/FAO ABBA Project

44

Ministry of Food Security and Research 2012

herds, distribution of breeding bulls, and establishment of an Achai breeding farm for breed improvement.

Sheep and goats also are the subject of both breeding and conservation programs. Local geneticshave beenthreatened due to indiscriminate breeding and lack of any policy, as the

Provincial government has until now not undertaken any program for appraisal, improvement or selective breeding of these breeds.

45 For example there are concernsregardingdilution of the genetics of vulnerable breeds such as Kari sheep which have characteristics such as high fertility, short gestation periods 46 and disease resistance, all traits which are vital for reducing risk in pastoral production systems. RecentLD&D Department policy initiatives supporting such conservation programs are shown bycommencement in 2012 of a project aimed at preservation and development of local sheep in Hazara and Malakand.

Policies for sheep genetic improvement, on the other hand, have been focussed on a program to breed and distribute exotic Rambouillet sheep. Thishas continued since the 1980s from the FAOsupported Jaba sheep farm at Mansehra, resulting in extensive cross-breed development in areas such as Swat. There is also a current program to establish a goat/sheep research centre in Swat, with an allocation of Rs 70 million, for improving local goat species through crossing with exotic breeds.

6. Disease surveillance, prevention and treatment

Livestock disease policy is the subject of NWFP Animal Contagious Diseases Act 1948 as well as old federal laws. It is also an item in L&DD Department Rules of Business, with a mandate described as “provision of animal health facilities and services to livestock farmers through curative and prophylactic measures”.

47 Qualified staff and veterinary assistants at 98 veterinary hospitals, 218 veterinary centres and 363 veterinary dispensaries are involved in surveillance, assisted by 7 diagnostic laboratories. A Rapid Response Team also exists to act in the event of disease outbreaks. The KPK Veterinary Research Institute is mandated to “control livestock diseases of economic and zoonotic importance”, mainly through vaccine production. Although

L&DD staff are legally required to undertake a range of control measures, officers in the field regard quarantine is a federal responsibility.

The L&DD Department stated it does not charge for animal disease treatment provided from district dispensaries, although maintains that producers are willing to pay. The future plan is to convert Veterinary Centres into Farmer Community Centres, which will provide a range of programs. Private treatment services are either not available, or do not have the capacity to offer an alternative.

Disease prevention through vaccination is undertaken by the L&DD Department as a supplydriven service organised to meet annual targets.Vaccination programs are charged for at a rate of cost of vaccine plus Rs2 per animal, and delivered according to a seasonal calendar, with specific weeks for particular disease programs. Previous surveys have indicated 48 low coverage of landless producers. Stated constraints to more effective coverage include lack of awareness and willingness of farmers, the capacity of staff, and the cost of vaccines. L&DD staff claimtreatment rates would be higher if specialist vaccination teams were engaged, on good salaries. At the current low level of coverage vaccine production is not a constraint, except for FMD which is produced under an

FAO/USAID program, and can be expensive depending on vaccine source.Field staff reported failure of available vaccines to protect against new disease strainsassociated with migrating

45

M Afzal and AN Naqvi (2004) Livestock Resources of Pakistan. Science Vision 9

46

S. Ahmad and M. Sajjad Khan (2008) Nature

47

KPK Livestock and Dairy Development Department website

48

ADB Livestock Development Project Report Small Ruminant Unit1993

flocks.This is in the context of the most recent study of Pakistan government vaccine production facilities 49 which noted significant inadequacies in production systems and quality control.

Monitoring and quality control of livestock medicines and vaccines is a responsibility of the federal

Health Department, with the Drugs Act 1976 covering production, registration and saleHowever the current legal basis for this since the 18 th Amendment, and the assumption of Provincial responsibilities have to be clarified. L&DD Department maintains it has the capability to do this, and should be given the responsibility.

50

7.Extension and capacity building

L&DD Department extension policy is reflected in the stated mandate: “provision of livestock production extension services to the livestock farmers through a network of veterinary institutions.” 51 . In fact the extension services lack any measure of performance other than animals treated or serviced with AI. Transfer of technical knowledge such as“livestock production extension”, promoted bythe Asian Development Bank-funded Livestock Development

Project,stopped when Project funding ceased before 2000. 52 At present there is a stated objective of recreating such a focus, although last year the application to fund a unit for this purpose under a Director of Production Extension was rejected.

There has been an active tradition of capacity-building for livestock personnel in the KPK L&DD

Department. This has been based around the previously Dutch-assisted Animal Husbandry Inservice Training Institute. Stated mandates of the Institute include training of extension workers for L&DD Dept, changing attitudes from curative to preventative, creation of male and female activists as livestock extension workers, and developing extension messages.

Extension programs targeting specific industry needs such as dairy production have been supported by agencies such as the University of Agriculture Faculty of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary

Science which has sponsored the development of groups such as the Sarhad Dairy Farmers

Association, and the Faculty aims to take a leading role in promoting dairy business development.

Government action has supported social welfarelivelihood initiatives for gender-based interventions intended to provide female livestock owners with training. Recently the Australian government’s Pak-Australia Dairy Extension Project wasco-opted toundertake dairy extension training forKPK officers in Punjab.

53

8. Research and development

Although there are two KPK universities, a Veterinary Research Institute, and a number of

“research” projects managed by the L&DD Department, there is no means of coordinating livestock research direction, of funding research using industry contributions, or of ensuring accountability from research bodies.

9. Animal Welfare

Prevention of cruelty to animals is a mandated function of KPK L&DD Department, but the policy basis for this, the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1890, is outdated in the light of changing attitudes of urban society, and changing methods of managing and treating production livestock.

There is no comprehensive regulatory requirements ensuring humane treatment of animals, and

49Bevan RE & HO Pakistan Veterinary Vaccine Review 2007

50

Dr Sher, Director L%DD, pers. Com.

51

KPK Livestock and Dairy Development Department website

52

ADB Pakistan Livestock Development Project Audit report 2004

53

Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research ASLP Program (2012)

there is no regard for the welfare of animals during transportation, sale and purchase in marketplaces, slaughter, or other management processes.

10. Livestock feed

For an industry which is based completely on feed production and utilisation there is no forage policy which supports forage seed development, stimulates appropriate research and supports development of feed as a commodity. In regard to processed feed there is no law regulating the animal feed quality in KPK, or penalty for selling unhealthy or injurious animal feed.

11.Rangeland management and pastoralism

Management of rangeland has been traditionally a Forest Department responsibility.The Forest

Sector Master Plan defines 48% of the area under Forest Department management as rangeland which is 4.893 million ha. The policy instrument is the Provincial Forest Ordinance 2002 which supports the Department’s guiding principles 54 of integrated resource management of land-use types and resource types, as part of the ecosystem. The Department’s policy regarding stakeholders is to encourage participation in natural resource management activities.Although funded to manage rangelands, 55 a with a sum of Rs 960 million over six years provided for rehabilitation and development of range and pasture lands, the Forestry Department focus is on forestry issues.

Broad delineation of rangeland in KPK is difficultas estimates range from 27.5% to 46.5% of total land area, depending on criteria for mapping distinction of wasteland and degraded forest. The area of rangeland in KPK was regarded by Government of Pakistan in 1973 as 5.68 million hectares 56 .

Much of this area is regarded as degraded. For example quoted in the World Bank Strategic

Country Environmental Assessment,in 1995 57 the area of degraded rangeland was mapped as

4,106,000 ha. This rangeland is estimated to carry at least 60% of the livestock of the province.Livestock numbers have increased by at least 3.5% per year over that period, and it is assumed thattheincreased grazing pressure has resulted in further degradation. Livestock production based on rangeland is becoming less stable as animal numbers increase, the fodder resource depletes, and climate change potentially tightens the knot.

It is significant that the biggest increase in livestock numbers has been with the goat component of herds. For pastoralists and subsistence herders indigenous goat breeds provide milk, hair and mutton as well as possessing high reproductive rates. That goats are also damaging to the environment through their destructive browsing behavior was recognized in the passing of the

West Pakistan Goat (Restriction) Ordinance, 1959, and adopted by the Province through Adoption of Law Order 1975, which prohibits keeping and grazing of goats, except in animal sheds. There is now no effort to ensure compliance with this law, although goats are associated with accelerated loss of tree cover, estimated at over 2% annually by the World Bank.

58

The landless nomadic and transhumant communities which traditionally graze these rangelands are marginalised due to forestry and cropping development, degradation of grazing areas, exploitation by health and marketing service providers and land tenure conflicts over customary and statutory rights of use. Their traditional response to insecurity is not to stock more conservatively but to increase numbers as a “safety net”. However with progressive loss of rangeland forage resources a degree of self-limitation might be expected with these production

54

KPK Forestry Department website

55

KPK Comprehensive Development Strategy of 2010-17 (2010)

56

PARC (1993) “Sheep production in Pakistan”

57

World Bank Strategic Country Environmental Assessment (1995)

58

World Bank Strategic Country Environmental Assessment (1995)

systems. There is some evidence for this in the flattening off of livestock increases, for example in the Chitral data reported by Nasser. 59

Table 9: Chitral livestock trends

1986 census

1996 census

% Change 2006 census

% Change

Cattle

Sheep

Goats

Total

100,083

113,627

221,070

434,780

173,262

188,822

335,780

697,864

+ 42%

+ 66%

+ 51%

+ 60%

174,842

181,146

347,977

703,965

+

1%

- 4%

+4%

+4%

60

Data from Khan and Ahmad (2000) relating to nomadic graziers in Swat and Malakand districts support this with suggested figures of more than 50 % reduction in the size of Ajar sheep/goat flocks, and similar substantial reductions in Gujar cattle herds. Reasons advanced included squeezing of grazing resources by afforestation projects,closureof trekking routes, herders moving from grazing to employment, and lost access to privatized hillsides.

With the aim of addressing the current policy gap a newrangeland policy has beendrafted by The

Pakistan Forest Institute for the KPK Forest Department. This proposed policyis clearly aimed at environmental protection and identification of biodiversity threats, and will depend on extensive rangeland data collection and interpretation, to enable formulation of proposed range management plans. Conservation outcomes will mainly depend on natural regeneration of rangeland. Elements of the policy relating to rangeland include regulations to specify livestock movement routes, fixed periods of stay in grazing areas, and grazing fees to be set which are related to the productivity of the pasture.Policies will also involveawareness-raising regarding over-grazing, and capacitybuilding for grazing communities. This will be part of a “social range concept” and the forming of graziers associations, based partly on the Forest Department’s village land-use planning techniques.

Institutional changes will notreduce the Forest Department’s continued responsibility for rangelands, but a new Rangeland Development Advisory body proposed, with representation from a range of agencies including L & DD Department.AProvincial Range Development Fund is also proposed.Future rangeland management will require cooperation and coordination of overlapping initiatives, for example livestock health (eg vaccination campaigns) and herder livelihood initiatives specified in the draft policy.

L&DD Department has not indicated if it supports the concepts involved in the draft Policy.

However the Department has responded to increasing threats to pastoralist communities by establishing a Pastoralism Unit.

61 This will perform functions including compiling a comprehensive database, preparing development programs which address some of the constraints for the pastoralists, improving health and marketing services, and generally enhancing the capacity of the pastoralists to manage their traditional pursuits. The unit was allocated Rs150 million in

2012, and initially funded Rs35 million.In addition the Department has committed to support two pilot pastoral systems: the Burwahai-Haripur system (east of Indus River in Himalayan region), and the Mahodand-Khadokhei system (west of the Indus in the Hindu-Kush region). Rs 150 million have been allocated over three years to strengthen social capacity, enhance winter fodder supplies, establish transit facilities and services along movement routes, introduce financial support mechanisms, and monitor socio-economic and ecological impacts.

59

M.Nasser et al “Pastoral Practices in High Asia” ed Kreutzman

60

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

61

Landless Mobile Pastoralists Workshop Proceedings, Islamabad 2012

12.CurrentKPK policy reviews

12.1 Provincial Reform Program

The KPK Provincial Reform Program 62 in 2011 encouraged policy review by government and industry, advocating multi-stakeholder “think tanks” to provide independent advice and feedback.

The outcome was a “Policy Action Plan for Implementation of Comprehensive Development

Strategy on Livestock Sector” 63 in consultation with Professor Muhammad Subhan Qureshi, Dean of the Faculty of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Science at University of Agriculture. Reorganization of the L and DD Department is included in the strategy, based on wide consultation with provincial stakeholders. The financial requirement for implementation of this plan was estimated at Rs 200 million, with a need for outside investors. An autonomous Board and Services

Network has been proposed to promote commercialization and link stakeholder inputs to service.

12.2 FAO Agricultural Policy for KPK

A comprehensive policy review of agricultural and livestock policy was carried out by FAO in

2012 64 following a request for assistance by KPK government. This review details a number of strategies for agriculture, and includes recommendations for enhancing productivity and competitiveness associated with dairy, meat and wool value chains through removing price controls. The report also recommends limiting livestock movement out of the province for processing, improving livestock market systems, increasingmarket transparency and increasing quality control through improved food safety measures and Halal certification.

Otherrecommendations resulting from the FAO study which are relevant to livestock policy include the importance of the private sector in taking the lead in market development. It suggests the need for NGOs and community-based organizations to agree to protocols for transparency and accountability and tointerface with the government and private sector in a multi-stakeholder approach

KPK rangeland policy is covered by the study, with recommendations including the need for regulations for protection, and for proper mapping, capacity assessment, planning, and monitoring,

Also recommended is protection of the livelihoods of dependent pastoral communities, and promotion of facilities for transhumant communities.Community organizations and NGOs are instructed to resolve conflicts and develop ownership for common rangelands.

12.3 Previous policy reviews

The pace of policy development can be assessed in the light of previous opportunities to examine policies and introduce reform. The Asian Development Bank Livestock Development Project twenty years ago promoted some of the same concepts now discussed. These included encouraging private sector involvement, removing price controls, improving certification of medicine quality, and improved quality assurance for products such as milk. The author of this report, after field surveys in KPK in 1993, at that time recommended reform of inefficient and corrupt livestock markets, review of breed development policies particularly the rationale for distribution of exotic breeding stock of doubtful genetic value, and a review of disease prevention programs particularly regarding the effectiveness of vaccination and de-worming programs for landless and mobile pastoralists.Attention may have been paid to some of these issues, but in general the impression is one of no change after twenty years.

62

Report (2011) “Towards Citizen-Centric Governance”

63

Reported Prof M S Qureshi, Pakissan 29/4/13

64

FAO (2012) KPK Agriculture Policy – A Ten Year Perspective.

Section IV. International livestock policymodels