Literature Review

advertisement

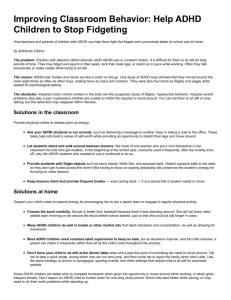

Running Head: EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION Evaluation of the Implementation of Behavioral and Instructional Management Strategies for Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Alexandra Benton Seattle Pacific University 1 EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 2 Evaluation of the Implementation of Behavioral and Instructional Management Strategies for Students with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common disorders affecting 8.8% of the youth population (Spiel, Evans, & Langberg, 2014). Students with ADHD are often inflicted with poor grades, failure to complete assignments, and high rates of course failure (Spiel et al., 2014). Within a given classroom students with ADHD are more likely to be off-task, disorganized, and not comply with teacher requests when compared to their non ADHD peers (Spiel et al., 2014). These trends continue into adolescence and often lead to course failure, and lower level placement (Spiel et al., 2014). Clearly ADHD affects both behavior and academic achievement. Students with ADHD are sometimes given Individualized Educational Programs (IEP) or 504 Plans. Given the relatively large number of students who suffer from ADHD it is prudent to ensure that teachers are supporting them with evidence-based strategies for both behavior and instruction. Individualized Education Program and 504 Plans for Students with ADHD The large number of students with ADHD makes it important that the goals and services laid out in IEP and 504 Plans align with current research, as this is what Spiel et al. (2014) attempts to do and why this paper is relevant to special education. Spiel et al. (2014) spend the introduction explaining what ADHD is and how it affects students, this information is summarized in the first paragraph of this paper. Spiel et al. (2014) also touch on the designation between IEP and 504 Plans and how doctors and sometimes school psychologists often need to make decisions about whether students with ADHD are eligible for an IEP or a 504 plan. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA) allows the creation of IEP which allows for individualized services (Spiel et al., 2014). Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is a civil rights law that protects individuals with EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 3 disabilities rights to fully participate with their peers, to the extent possible, this act allows the creation of 504 plans (Spiel et al., 2014). One resource that is used by school professionals when creating IEPs and 504 Plans is the 2008 Federal Department of Education manual on teaching students with ADHD which outlines 128 services for students with ADHD (Spiel et al., 2014). IEPs must include the student’s present academic achievement and functional performance, measurable annual goals and objectives, and services designed to address those goals (Spiel et al., 2014). 504 plans often include similar sections to IEPs, but they are not required (Spiel et al., 2014). Therefore, need based goals are aspects of both IEP and 504 Plans, a fact which Spiel et al. use to their advantage in order to determine whether IEP and 504 Plans for students with ADHD conform to research based practices. The study gathered and analyzed the most recent IEP or 504 Plans of 97 middle school students. The measurable annual goals and objectives, the present academic achievement and functional performance, and provided services were coded and recorded for each students’ plan. The authors then completed a literature survey of peer reviewed articles that focused on each of the 18 services found in the IEP and 504 Plan survey. The authors ensured that all articles were specifically about students with ADHD. The authors found that the majority (85%) of IEP’s present academic achievement and functional performance included nonacademic/behavioral functioning. The authors postulate that this finding is good as it shows that IEP teams are paying attention to common problem areas for students with ADHD. Common problem areas are: off-task behavior, homework completion, compliance, social-skills, and organization. However, the authors found that fewer than half (47%) of students with an IEP had measurable annual goals and objectives that addressed this nonacademic/behavioral functioning. For example, even though a student may have an issue with off-task behavior, and will receives supports, perhaps in the form of tasks broken up into smaller EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 4 pieces (Zentall, 20005), the student will have no measurable or observable goals in their IEP or 504 Plans. So even though these areas of need are recognized, close to half of the IEPs had no goals for improving student behavior. This study found that the main difference between the IEP and 504 Plans were the amount of services given. There were 18 services listed between all IEPs and 504 Plans, they were: extended time (tests), small group (work time), prompting (to keep student on task), test aids, read-aloud, breaks, study support, reduction (shortening tasks), behavior modification, oneon-one, modeling skills, preferential seating, material organization, planner organization, adapted grading, copy of notes, dividing tasks, and (increase of) parent-teacher contact. With the exception of one category (modeling skills) all services that were listed for IEPs were also on 504 plans. Of the listed services given, eight (out of 18) were listed more frequently for students with IEPs. The authors hypothesize that school psychologists and school based teams are making decisions upon the amount of services required to meet the student’s needs rather than the type of service that may be required when deciding between an IEP or 504 Plan for students with ADHD. This would be a serious problem as IEP and 504 Plans should be based on the supports the student needs, not the number of supports. This could indicate serious issues with special education within the country. The authors further found that of the services listed in IEPs and 504 Plans the majority (85%) were listed in the aforementioned 2008 Federal Department of Education manual on teaching students with ADHD. The authors hypothesize that this is due to this manual having a large influence on school personnel who decide on services. Unfortunately the authors found that many of the most commonly used services had very little research to support them. For example, behavior modification had the largest research base to support it, however it was used only 25.8% in IEPs and only 5.3% of the time in 504 Plans. On the other hand, 80.3% of IEPs and EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 5 76.3% of 504 Plans listed extended time on tests as a service, the research shows that the use of extended time on tests has mixed results for students with ADHD. Furthermore, three of the top ten services (test aids, breaks, and study supports) had no research supporting their use for students with ADHD. In the next section this trend of few behavioral supports is also seen, but in students without IEP and 504 Plans. Finally the authors argue that if the Federal Department Education manual should update their list of services for ADHD students to align more with current research as the manual seems to have a large effect on the making of IEPs and 504 Plans. Behavioral and Instructional Techniques for Students with ADHD While IEP and 504 Plans are an important part of managing the behavior and achievement of students with ADHD only one quarter to one half of students with ADHD receive these additional services (Spiel et al., 2014). Since so many students who have ADHD do not receive additional services it is important to assess how teachers manage both the behavior and instruction of these students. Two studies of teachers in Canada have shed some light on how knowledge and perception of ADHD affects instructional strategies used by those teachers. The first study (Martinussen, Tannock, & Chaban, 2010) was completed in Ontario, Canada and used individual surveys of teachers as their data. They found that the more training in ADHD general education teachers had the more likely they were to use recommended behavior management approaches and instructional supports and strategies. However, very few teachers who took this survey had received moderate or extensive training in ADHD. Furthermore, while general education teachers did report use of supported behavior management techniques for students with ADHD they were far more likely to implement positively focused behavior management and far less likely to use more individualized behavior supports like EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 6 behavior contracts or the daily report card. The authors postulate that low usage rates of individualized behavior supports was likely due to time limitations. The second paper (Blotnicky-Gallant, Martin, McGonnel, & Corkum, 2015) also uses surveys to gain insight on teachers but this time in Nova Scotia, Canada. This paper surveyed not only teacher use of management practices, but also teacher knowledge of ADHD, and their beliefs about ADHD. Blotnicky-Gallant et al. (2015) also found that teachers were less likely to use more intensive behavior and instructional management practices. Furthermore, teachers’ beliefs about ADHD were correlated with the use of evidence-based behavioral strategies. Teachers that had a more negative beliefs about ADHD were less likely to use evidence-based behavioral management strategies. Beliefs about ADHD, however, were not correlated with usage rates of evidence-based instructional strategies. Blotnicky-Gallent et al. (2015) also found that teachers who had more general knowledge of ADHD (as measured by a questionnaire) had more positive beliefs about ADHD. However, general knowledge of ADHD was not significantly correlated with use of either behavioral or instructional management strategies. The authors postulate that this could be due to the questionnaire they used not taping into the sort of knowledge of ADHD that would relate to a teacher’s classroom practice. The authors further suggest that if general knowledge is not effective in promoting evidence-based practices that teacher-education programs should focus specifically on teaching these strategies. Evidence-Based Instructional and Behavioral Management Strategies Given the limited use of evidence-based practices for both instructional and behavioral management strategies in classrooms it seems prudent to explore a few of the options available to teachers. Both Blotnicky-Gallent et al. (2015) and Martinussen et al. (2010) found that teachers were more likely to use simple strategies that required little time to implement. While EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 7 this may be appropriate for instructional strategies it appears that more intensive behavioral strategies tend to work better. A paper published in the journal Psychology in the Schools compiled lists of evidencebased practices for guiding selective attention, as well as maintaining attention in students with attentional problems (Zentall, 2005). Of the 20 strategies suggested for guiding student attention only six of them seemed to require extra time to implement, either due to after-school training of teachers, or in class time for reflection or training of students. Other suggestions of strategies seemed easily implemented, for example putting a mirror on the desk of a student with ADHD, or removing non relevant information from a visual. All of the strategies given for maintaining student attention would not take a great deal of time, which makes sense as these strategies are mainly implemented during class when students are present. One behavioral strategy identified was under the parent-teacher contact service section in Spiel et al. (2014). While they don’t present any papers that deal with this they do mention that the Daily Report Card is empirically supported. Fabiano, Vujnovic, Naylor, Pariseau, and Robins (2009) studied the stability of Daily Report Card data over time to see if this method was able to capture significant information on the behavior of students with ADHD. The Daily Report Card is a survey that a teacher fills out several times a day on whether or not a student has me their behavior goals (Fabiano et al., 2009). This article shows that the behavior of students with ADHD can be tracked through Daily Report Cards (Fabiano et al., 2009). The Fabiano et al. (2009) paper also showed that ADHD students’ behavior varies greatly from dayto-day, which highlights the importance of frequent progress monitoring. Since this study was not included in the Spiel et al. (2014) article it raises doubts as to the validity of strategies in that publication as Fabiano et al. was published in 2009. This overlap suggests the possibility that the EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 8 Spiel et al. (2014) authors missed other research on ADHD students. Even with this lapse the general findings presented in the Spiel et al. (2014) article seem reasonable. Having a working behavioral plan for a student with ADHD can increase student attention and help focus them on instruction (Gormley & Dupaul, 2015). However these plans are often lost when a student moves grades or teacher. Gormley and Dupaul (2015) studied the effect of teacher-to-teacher consultation for students with such behavioral plans for their ADHD. This study took place at the elementary level and helped teachers develop well-working behavioral plans for student over the school year. The next fall both the new and previous teachers would meet and the new teacher would be informed on the implemented plan for that student. All students showed gains on this program from their baseline levels, which were taken in the fall of the second year. However this study only had three participants, all of whom were in grade school and Hispanic. Clearly this topic should be explored further, especially it’s possible implementation in the secondary level where many more teachers would need to be involved in the behavior plan. Summary An overall trend has been observed through these studies that behavioral modifications and strategies that require any extra time from the teacher or during class time are rarely implemented. There is some evidence that a more training about ADHD and more positive beliefs leads to a higher usage of evidence-based strategies. However, general knowledge of ADHD does not correlate to a higher usage of evidence-based practices. This is likely due to the workload of teachers being high, and standards that allow for little time in class for student reflection and teaching of behavior plans to students. However, Zentall’s (2005) list of strategies highlights that there may be fewer strategies that require an extra amount of time versus those that can be done easily or in class. If this is true than the conclusions drawn by Martinussen et al. EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 9 (2010) and Blotnicky-Gallant et al. (2015) were incorrect, as the ratio of high intensity to low intensity behavior management strategies is not equal. Finally, instructional strategies supported by the literature seem to mostly be easy to implement and focused on task duration and stimulation management. I chose this topic because I grew up with a brother with severe ADHD. While I have adapted coping mechanisms to deal with my older (often annoying) brother I know my students are not equally equipped. During my internship I often found myself ignoring poor behavior of my ADHD students as that is how I learned to cope with my brother. After some reflection I have come to realize that my tendency to ignore and tolerate outbursts is detrimental to both my general education students and my students with ADHD. My purpose in choosing this article was to learn more about appropriate ways to help promote appropriate behavior in my students who have ADHD. The review of literature presented in these articles certainly helped me identify some resources. EVALUATION OF IMPLEMENTATION 10 References Blotnicky-Gallant, P., Martin, C., McGonnell, M., Corkum, P. (2015). Nova Scotia teachers’ ADHD knowledge, beliefs, and classroom management practices. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 30, 3-21. Fabiano, G. A., Vujnovic, R., Naylor, J., Pariseau, M., & Robins, M. (2009). An investigation of the technical adequacy of a Daily Behavior Report Card (DBRC) for monitoring progress of students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in special education placements. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 34, 231-241. doi:10.1177/1534508409333344 Gormley, M. J., Dupaul, G. J. (2014). Teacher-to-teacher consultation: Facilitation consistent and effective intervention across grade levels for students with ADHD. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 124-138. doi:10.1002/pits.21803 Martinussen, R., Tannock, R., Chaban, P. (2010). Teachers’ reported use of instructional and behavior management practices for students with behavior problems: Relationship to role and level of training in ADHD. Child Youth Care Forum, 40, 193-210. doi:10.1007/s10566-010-9130-6 Spiel, C. F., Evans, S. W., & Langberg, J. M. (2014). Evaluating the content of Individualized Education Programs and 504 Plans of young adolescents with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. School Psychology Quarterly, 29, 452-468. Zentall, S. S. (2005). Theory-and evidence-based strategies for children with attentional problems. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 821-836. doi:10.1002/pits.20114