File - Kimberly Guppy`s E

1

Assignment 5 – English 785 | Kimberly Guppy

To Deeply Ponder Splitting the Infinitive

English grammarians in the eighteenth century developed many of the stylistic rules we follow today, from spelling to syntactic structures. The majority of these rules were chosen through personal preference by men of learning, the self-appointed authority of English grammar. These language critics were hoping to promote a higher status for the language, refine and fix it, as well as cement a proper form of the language for generations to come.

Through the model of Latin, the study of etymology, and the application of logic they attempted to create this standard. By way of manuals and dictionaries they later found success in the adoption of many of these rules in writing. Many of these rules are explored and promoted in modern day grammar manuals and dictionaries, such as those that will be discussed in this essay. Among the entries is the Split Infinitive, a source of modern dispute with origins rooted in this subjective 18th century language overhaul and no real grammatical issue.

This essay will explore the modern day interpretation of the split infinitive, examine how manuals guide usage of the feature, as well as critique the manual writers as compared with their 18th century counterparts. To begin: what is the split infinitive, and why is it included in modern day grammar manuals?

Although there is some disagreement among the manuals about the split infinitive, all agree that it is the insertion of a word or phrase, usually an adverb, between the word to and the infinitive form of the verb. The history of its usage is included in several of the manuals, and can be briefly summarized as being an incorrect analogy from Latin. The American Heritage guide concisely describes this analogy: “The thinking is that because the Latin infinitive is a

Assignment 5 – English 785 | Kimberly Guppy single word, the English infinitive should be treated as if it were a single unit,” (34-35).

Unfortunately for 18th century grammarians, this is an ill-conceived comparison because, unlike Latin, English is not an inflective language. In 1866, grammarian Alford was “shocked to discover that such a construction existed” and its use was quickly condemned by grammarians, although its usage continued despite their abhorrence of it (Webster 868). The evidence provided in these manuals shows the split infinitive was directly affected by grammarians’ insistence on using Latin as a model, as well as personal preference for a certain style.

This personal preference resonates to this day in modern style guides, which dislike the use of the split infinitive because it is “inelegant” and “an ugly thing,” (Cambridge 512, Fowler

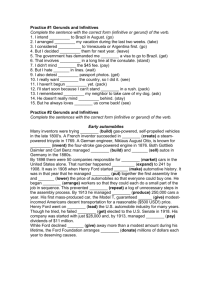

329). Of the eight manuals included in the analysis for this essay, the majority suggest that the user avoid using the split infinitive in writing based merely on this precedent set by 18th century grammarians. Table 1 below, organized chronologically, explores the opinions of the various manual writers on this topic.

2

Assignment 5 – English 785 | Kimberly Guppy

Table 1: Grammar Manual Information

Fowler (1949)

Bernstein (1978)

Webster (1989)

Oxford (1994)

Partridge (1994)

American Heritage

(1996)

Authority Background Description

Exploration of rules "An ugly thing," but usage as followed by writers does not define good or bad writers.

Personal or

Research Based

Research based on observing written works

Self-proclaimed grammarian, newspaper columnist

Grammarians of the 18th/19th centuries chose "for some reason that is not entirely clear." Personal

Multitude of sources, from historical and present-day as well as personal preferences of writers

Alford, 1866, shocked it exists, condemns use.

Research Based

Unclear based on introduction. Intent to provide guidance.

sentences.

Self-proclaimed, uses own judgements

Usage Panel: survey of modern writers' preferences

Artificial rule that can produce unnecessarily contorted

Becoming more frequent in use. Not to be encouraged,

"inelegant"

Based on false analogy with

Latin. Latin infinitive is a single word, so "to+verb" should be treated as single unit.

Unclear based on introduction.

Personal

Research uses

Personal Opinions

Current Ruling

Avoid the Split

Infinitive?

Do not use it. But it is OK to use it.

Unclear.

The rule is "on its way out" No.

Awkward avoidance has created more bad writing than use of it.

Commentators tell us to avoid except for clarity.

No rational basis.

Yes and No.

Good writers avoid.

Recommended that adverb be placed before/after infinitive, unless leads to clumsiness or ambiguity.

Yes, but...

Avoid when possible.

Occasional use to avoid ambiguity.

Yes, but...

Strunk (2000)

Cambridge (2004)

Professor, selfproclaimed expert

Multitude of sources to create

"single, international form for written communication"

Precedent from the 14th century down.

Misconceptions about

English infinitives (two parts that can never be split). Split infinitives were used for centuries before C18 C19 grammarians censored.

Subjective: "it's inelegant"

Personal

Research Based

Avoid. Except when it affects meaning or rhythm.

Avoid unless the writer wishes to place unusual stress on the adverb.

Yes, but...

Yes, but...

"DO NOT split an infinitive if the result is an inelegant sentence. DO split infinitives to avoid awkward wording, to preserve natural rhythm, acheive intended emphasis and meaning." Sometimes.

The manual writers’ authority is important to address in identifying the trustworthiness of these sources of information. Several of these manuals are well-researched and compiled by many scholars, while others are merely the endorsements of one or two self-professed grammar experts. The fact that half of the manuals are of the latter is of importance because it reflects how grammar is often shaped by a (self-)selected few, just as it was during the 18th century.

3

Assignment 5 – English 785 | Kimberly Guppy

Among the sources of background information provided on the split infinitive, there seems to be some correlation. Of those that comment on the explicit history of the split infinitive and its connection to Latin are the three major research based manuals, Webster,

American Heritage, and Cambridge. These three sources also go the furthest in depth in exploring historical and modern uses of the feature. The other sources either ignore the history, as with Fowler, or merely graze over the historical information, sometimes incorrectly as seen in Bernstein’s description: “the taboo against the split infinitive was clamped on writers by grammarians of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for some reason that is not entirely clear.” (113). The historical reasons behind this feature are important in making a claim about proper usage, and the discounting of this information by these guides is telling in how subjective grammarians are allowed to be.

The guidance provided by these manuals also comes from a variety of sources, from personal judgments by the self-appointed authorities to multifaceted reviews of current language usage compiled by great teams. It is interesting to see that the suggestions made by these different sources are not confined to the type of authority, as shown in Table 1. Bernstein and Strunk are both self-appointed experts but disagree on usage. The Webster and Cambridge guides, both of which use a myriad of sources also offer different suggestions for usage, as

Cambridge gives more explicit direction while Webster provides a mere overview of the prevailing opinions on the topic. Clearly the source of the information is not the sole guide in instructing users.

Despite the lack of reason behind the avoidance of split infinitives, all but two of the manuals explicitly suggest it should be avoided anyway. Interestingly, none of them say split

4

Assignment 5 – English 785 | Kimberly Guppy infinitives should never be used- in fact most of them say split infinitives have merit in certain circumstances, such as to avoid ambiguities and clarify intention of the writer. In the end those six sources are out to merely reinforce the old prescriptivist notions about split infinitives. But wait! Just there! “...are out to merely reinforce…” Does that adverb need to be moved? Should I have typed “...are merely out to reinforce…” instead? Is the form I used actually quite ugly and inelegant? Bernstein and Webster’s Dictionary would seem to disagree.

Bernstein, writing in the 1970s, was actually under the assumption that the rule about split infinitives was on its way out. He boldly claimed that since the usage of split infinitives had been increasing, it was bound to be an obsolete rule before long. Webster’s Dictionary, on the other hand, explores grammar from an entirely different perspective than the other manuals.

While the others provide explicit, detailed usage rules of a prescriptivist nature, Webster’s

Dictionary follows a more descriptivist approach. The original Webster is quoted in Brinton &

Arnovick, “he criticized those grammarians who ‘instead of examining to find what the English language is,…endeavor to show what it ought to be according to their rules’” (395). He was among the original descriptivists, and his legacy lives on in the modern version of Webster’s

Dictionary. The collaborators of the 1989 version go into great detail about the history of the split infinitive, as well as describing its prescriptivist uses today, but do not tell the reader how to use it. So should we?

After analyzing the multitude of opinions about the split infinitive, it is safe to say that writers should follow their hearts. Despite the heavy evidence in support of using split infinitives, the majority of the guides argue against its use for arbitrary reasons. Those that wavered in favor of its use, such as in the Cambridge guide, did so because of its prominence in

5

Assignment 5 – English 785 | Kimberly Guppy written form today, as evidenced by modern texts as well as opinions of highly regarded writers. Those who were more strict in their tone against its usage, such as Fowler and Strunk, were in favor of purifying writing, which again mirrors 18 th century grammarians’ goals of creating an English grammar. It is obvious that modern day prescriptivists have many of the same goals and attitudes about language use and language change as did their 18 th century counterparts. The split infinitive is, and perhaps never was, a language mistake, but rather the unfortunate prey of ill-informed scholars of old. Hopefully Bernstein is right in his argument that the less attention paid to this rule by modern writers, the less important it will become.

6