ASIA1030Tute3Group1

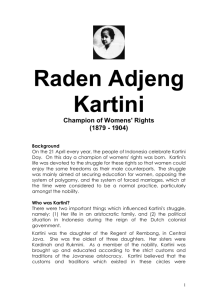

advertisement

Individual and Society in Asia and the Pacific B Group Assignment Elizabeth Bailetti Kirrilly McKenzie Lok Yiu Tutorial 3 Group 1 Proposal and Annotated Bibliography Wikispaces: http://asia1030tute3group1.wikispaces.com/Final+Proposal 1 Among the first Indonesian women to receive Dutch education in Indonesia, Raden Kartini, wrote letters to her Dutch friends on a range of feminist issues. These letters were first published in Door Duisternis tot Licht (Abendanon ed. 1911). It is this that we propose to base our presentation on looking at how Kartini's letters contributed to the nationalist movement in Indonesia. The letters of Kartini made a considerable contribution to the nationalist movement in Indonesia in the early to mid-20th century. They branched over a number of issues imposed on the indigenous people including education, gender equality and modernity (Coté 1992). Kartini’s views on these issues reflected key points for progression in Indonesia and were embraced by the Dutch in regards to their Ethical Policy (Stewart Taylor 1976, p. 640) while also being heavily influential during the movement for Independence (Tsuchiya 1990, pp. 76-78). The greatest mark of Kartini’s letters is exemplified in the Dutch initiated education policy, focussing on giving indigenous girls an education (Kartini et al. 1974, p. 83 ). This increase in Dutch education amongst the indigenous community, spurred on by the letters, saw rise to the growing nationalist movement and ultimately resulted in Indonesian Independence. In Kartini’s letter an integral part of the nationalist movement would be the mobilisation of women. This meant educating women. By educating women and including them in the nationalist movement there would be more support and more influence (Kartini et al. 1974, p. 93.) Kartini believed that by educating women they would have more influence in their communities and that they would work for the better of society (Kartini et al. 1974, p. 93.). Education would be most beneficial to the country and the establishment of the country (Kartini et al. 1974, p. 95). Kartini faced difficulties in reaching her goal. Like every feminist, Kartini faced structural barriers such as the difficulty in transforming cultural norms that brought negative impact on gender relationship and sensitivity on women’s conditions(Robinson et al. 2002, p.85). Moreover, Indonesian women’s unwillingness to embrace the idea from the West hindered Kartini’s progression. Through their own traditions, Indonesian women put limits on their freedom and right to achieve education (Robinson et al. 2002, p.85). The polygamous marriage and the way that 2 they were treated by men were critical, but women were still trapped in the “motherly” concept of the “good woman” (Beekman 1984, p.582). The lack of education and the emphasis on religious doctrines reinforced the narrow perception on the role of women, and made them to reject Kartini’s feminist movement. Annotated Bibliography Beekman, E. M. 1984. ‘Kartini: Letters from a Javanese Feminist, 1899-1902’, The Massachusetts Review, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 579-616. This article contextualises the figure of Kartini within the Javanese culture. It includes some extracts of her letters concerning her views on certain traditions such as marriage (p. 582) and the hierarchical structure in Javanese families (p. 581) as well as some thoughts on the variation between European and Javanese culture (pp 584585). 3 Frederick, William H. et al. Indonesia: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1993. This source provides interesting insight into the link between Raden Kartini and nationalism. This source also provides limited information on her achievements and what her letters brought for Indonesia. Kartini, R.A. and Coté, J. (trans). 1995. On Feminism and Nationalism Kartini's Letters to Stella Zeehandelaar 1899-1903. Victoria: Monash University Press. This is a compilation of extracts of Kartini's letters re-translated from the original Dutch into English. The extracts cover many of Kartini’s views on feminism and the importance of education. One letter in particular (pp. 68-76) takes particular interest in the value of medical training and the importance of the mobilisation of women in the work-field. Another letter (pp. 60-63) demonstrates the Dutch interest in Kartini’s views as well as placing importance on women in regards to the welfare of a nation. Kartini, R.A. and Coté J (trans), 1992. Letters From Kartini An Indonesian Feminist 1900-1904. Victoria: Monash University Press. This is a compilation of the complete correspondence from Kartini to Abendanon, translated from the original Dutch. As it is the complete correspondence, it includes many of the more personal aspects in her writing than other editions, allowing a more humanistic perspective of Kartini’s figure to form. As well as this, the letters vary between Kartini’s main interests in feminism and social progression, and due to the nature of the recipient of the letters, include highly insightful information on these topics. Kartini, R.A. and Taylor J. (trans) 1974. ‘Educate the Javanese!’ Indonesia, vol. 17, pp. 83-98 . This is a memorial Kartini addressed to the Dutch government in 1903, here it has been translated and given an introduction by Jean Taylor. The memorial puts a particular emphasis on education, arguing its necessity in a modern society (p. 86) as well as the integral role of women in a progressing moral society (pp. 86-87). Kartini continues throughout the memorial by specifying the particular issues in achieving this goal and the overall benefit it would have for her people. 4 Hellwig, Tineke et al. The Indonesian reader: history, culture, politics, Durham: Duke University Press, 2009. This book, particularly the chapter titled Pioneer of Women’s Rights: Raden Kartini, provides useful insight into Raden Kartini’s life and gives a detailed introduction, in which it is followed by some of her letters. This layout of the chapter provides important information which links her letters to her nationalistic and feminist views. Pols, H. 2008. ‘Medical Students and Indonesian Independence’ Health and History, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 146-150. This is a review of the Museum of National Awakening which features Kartini. More importantly, however, the review details the critical role medical education had in Indonesia in relation to the nationalist movement. Many nationalist figures were born from the medical education implemented through Dutch policy in the early to mid20th century (p.147). This validates some of what Kartini had covered in her letters, inclusive of a strong advocacy towards native directed medical education. Robinson, K.M. and Bessell S. 2002. Women in Indonesia: gender, equity and development. Institue of Southeast Asian Study, Singapore. This book provides general information of the actual situation of Indonesian women, with interviews from Javanese women about the thought of feminism and Katini's feminist movement. (pp. 80-87) Stewart Taylor, J. 1976. ‘Raden Ajeng Kartini’, Signs, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 639-661. This article is a general overview of who Kartini was and how she was received throughout the native and Dutch community. In particular, it details the practical effects of her work, from how her letters influenced Dutch policy (p. 640) to the founding of the Kartini Schools (p. 659). Tsuchiya K 1990 ‘Javanology and the Age of Ranggawarsita: An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Javanese Culture’ in Kahin A, Ludgate R and Millar Dolina 5 (eds) Reading Southeast Asia:translation of contemporary Japanese scholarship on Southeast Asia, Vol 1, Cornell University Press: New York, 75-108. This chapter focuses on Kartini as an initiator of nationalism within the Indonesian community (p. 76). It looks at her favourable view on Dutch and shows that the embrace of a language would be the embrace of all that is taught in that language, including movements of modernity and nationalism (p. 78). Vandenbosch, A. 1943. ‘The Effect of Dutch Rule on the Civilisation of the East Indies’, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 498-502. This article was written toward the end of Dutch colonialism and argues that the native culture had been preserved due to limited native access to Dutch education. Kartini is mentioned (pp. 500-501) in relation to her education movement but the article then continues to explain the native’s hesitation in embracing such a movement as well as some reasons to resist it from a Dutch perspective (p. 501). 6