Relationship Between Balanced Literacy Instruction and First Grade

advertisement

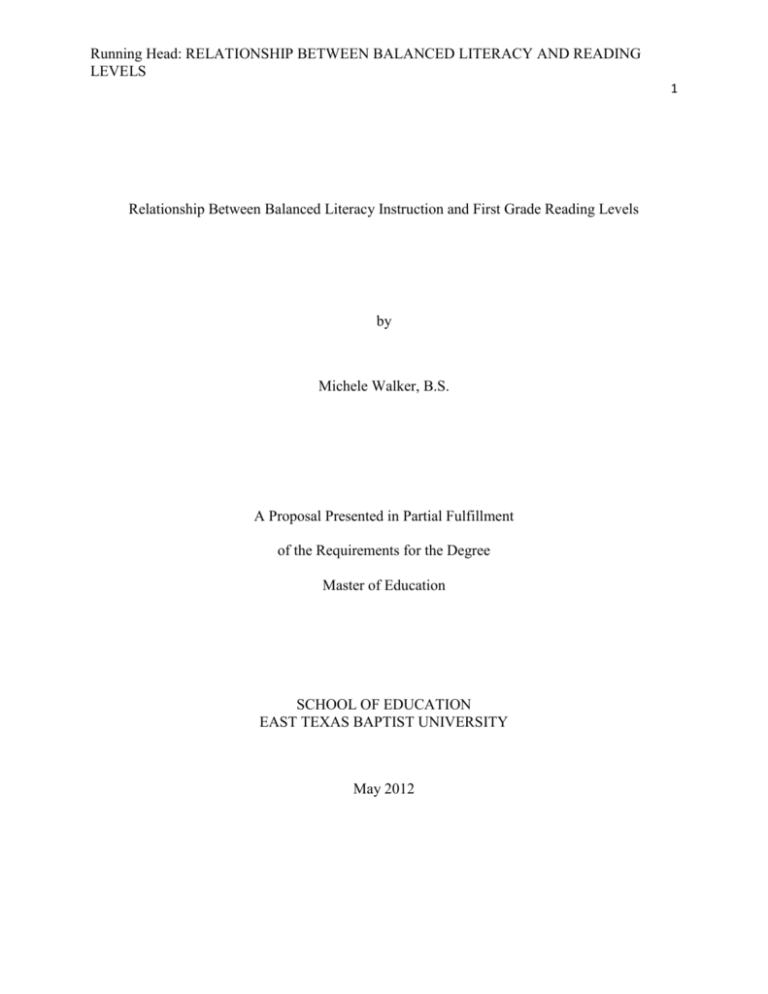

Running Head: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY AND READING LEVELS 1 Relationship Between Balanced Literacy Instruction and First Grade Reading Levels by Michele Walker, B.S. A Proposal Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education SCHOOL OF EDUCATION EAST TEXAS BAPTIST UNIVERSITY May 2012 2 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1.1 Response to Intervention Pyramid Figure 1.2 First Grade Developmental Reading Assessment Level Percentages Figure 1.3 Kindergarten Developmental Reading Assessment Level Percentages Figure 1.4 Four Kinds of Reading Figure 1.5 Running Record Form Figure 1.6 Reading Level Conversion Chart 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ..............................................................................................................2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ......................................................................................................3 CHAPTER 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................5 Purpose of the Study ........................................................................................................7 Theory .............................................................................................................................10 Balanced literacy instruction......................................................................................10 A framework for literacy learning .............................................................................10 Developmental Reading Assessment 2 ......................................................................15 Response to intervention ............................................................................................16 Definition of Terms.........................................................................................................17 Balanced literacy instruction.....................................................................................17 Guided reading ..........................................................................................................17 Components of reading instruction ...........................................................................18 Running records .......................................................................................................18 Developmental Reading Assessment 2 .....................................................................18 Research Questions .........................................................................................................18 Hypothesis.......................................................................................................................19 Limitations of Study .......................................................................................................19 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................21 2. Literature Review.............................................................................................................22 Effective Reading Instruction .........................................................................................22 Balanced Literacy Defined .............................................................................................24 Guided Reading ..............................................................................................................25 Response to Intervention.................................................................................................26 Effective Professional Development...............................................................................29 Summary .........................................................................................................................31 3. Methodology ....................................................................................................................32 Research Design..............................................................................................................32 Sample.............................................................................................................................32 Instrumentation ...............................................................................................................33 Procedural Details ...........................................................................................................34 Validity and Reliability ...................................................................................................36 Data Analysis ..................................................................................................................38 4 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................38 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................39 APPENDIXES .....................................................................................................................44 A: Appendix H as used by the school .............................................................................44 B: DRA2 continuum for level 16 ....................................................................................45 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 5 Relationship Between Balanced Literacy Instruction and First Grade Reading Levels Chapter 1 Introduction “Research now shows that a child who doesn’t learn the reading basics early is unlikely to learn them at all. Any child who doesn’t learn to read early and well will not easily master other skills and knowledge, and is unlikely to ever flourish in school or in life.” (Moats, 1999, p.5) There are those children who will learn to read in almost any educational setting they are placed in. However, there is a portion of the population that will only learn to read when they are taught in an “organized, systematic, efficient way by a knowledgeable teacher using a welldesigned instructional approach.” (Moats, 1999) It is the responsibility of the teacher and school to ensure that all children have the opportunity to learn to read. When a child struggles the school intervenes. The common goal of the U.S. Department of Education, the states, and the local school districts is for all students to be reading at or above grade level by the end of third grade. This goal was established because children who are not proficient readers by the end of fourth grade are not likely ever to be proficient readers. (Learning Point Associates, 2004, p.2) The International Reading Association (2008) describes RtI as a multi-tiered process that provides services or interventions to struggling learners at increasing levels of intensity. Response to Intervention is a means for early identification of students experiencing academic struggles in reading. This Response to Intervention (RtI) tiered approach offers more intensive RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 6 instruction or intervention with each tier. The Texas Education Agency describes Tier 1 instruction as high-quality classroom reading instruction available to all students. Tier 2 interventions are then provided for students who do not make adequate progress at tier 1. Tier 2 intervention is characterized by intensive, systematic instruction in a smaller group setting which is supplemental to tier 1 instruction. Students who do not make progress with tier 2 intervention plus tier 1 classroom instruction are then moved to tier 3 interventions. Tier 3 intervention is characterized by even smaller group instruction possibly even 1 on 1. Subsequently, students who do not make adequate progress at tier 3 are then evaluated for special education services (Gersten, et. al., 2008 p.4). The Texas Education Agency reports in the 2008-2009 Response to Intervention Guidance document that tier 1 instruction is adequate for approximately 80% of students. Only 15% of students are expected to need tier 2 interventions while only 5% are expected to need tier 3 interventions. Larger percentages of students needing either tier 2 or tier 3 intervention suggests a lack of high-quality classroom instruction at tier 1 (Texas Education Agency, 2008, pp.1-2). See figure 1.1. Figure1.1 Response to Intervention Pyramid Tier 3 5% of students Tier 2 15% of students Tier 1 80% of students RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 7 Purpose of the Study Historically, student reading achievement in first grade at Emerald City Elementary has been lacking. The school uses the Developmental Reading Assessment 2 published by Pearson as the measure of student reading levels at the beginning, middle, and end of each school year for students in kindergarten through third grade. During the 2008- 2009 academic year only 50% of the first grade students ended the year on or above reading level as based upon the Developmental Reading Assessment 2 (DRA2). In the 2009- 2010 academic year only 55% of the first grade students ended the year on or above reading level as based upon the DRA2. Then in 2010- 2011 only 49% of the first grade students ended the year reading on or above level as measured by the DRA2. As per the campus RtI process, any student scoring below grade level in reading as based upon the DRA2 is eligible for tier 2 reading intervention services. This would mean that on average 48.6% of the first grade students are in need of tier 2 services in reading. Refer to Figure 1.2. The principal deemed these percentages of first grade students reading below grade level at the end of the academic year as unacceptable. The principal of Emerald City Elementary knew that making changes to the first grade reading program (tier 1 classroom instruction) was of upmost importance. The large number of students requiring tier 2 and 3 interventions in first and then second grade put an undue stress upon the Response to Intervention (RtI) process and reading interventionists. Changes had to be made in the tier 1 classroom instruction so that the number of students requiring tier 2 and tier 3 interventions would hopefully decline. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 8 During the 2011-2012 school year all of the kindergarten teachers at Emerald City Elementary received training on balanced literacy instruction which included the four kinds of reading as described by Fountas and Pinnell: shared reading, read alouds, guided reading, and independent reading. The teachers implemented the model and attained a measure of success as determined by the Diagnostic Reading Assessment (DRA2) which is used to assess student reading levels. At the end of the 2011-2012 school year 87% of the kindergarten students were reading on or above a level three independently. Because of the success in kindergarten the principal of Emerald City Elementary has decided to continue this training and model with the first grade teachers. Refer to figure 1.3. Figure 1.2 First Grade Developmental Reading Assessment Level Percentages First Grade End of Year DRA 60% 58% 56% 54% 52% 50% 48% 46% 44% First Grade End of Year DRA RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 9 Figure 1.3 Kindergarten Developmental Reading Assessment Level Percentages Kindergarten End of Year DRA 88% 86% 84% 82% 80% 78% 76% 74% 72% 70% 68% Kindergarten End of Year Even though balanced literacy is considered to be an effective means of instruction there are still first grade teachers on the campus who do not have buy-in. They do not use all five components of reading as suggested by the National Reading Panel: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. They use a stand and deliver, heavy phonics skill-based means of instruction. The use of continuous text and guided reading is limited. Therefore, during the 2012-2013 school year the first grade teachers at Emerald City Elementary will receive training on the components of an effective balanced literacy approach to reading instruction specifically the effective use of the four kinds of reading and the five components of effective reading instruction. The teachers will then implement this method of reading instruction. This proposed project will be a causal-comparative research study to examine the RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 10 effect of balanced literacy instruction as implemented by the first grade teachers at Emerald City Elementary in rural Northeast Texas on the end of year reading levels of the first grade students. Data from the 2011-2012 school year (before the use of balanced literacy) will be compared to data from the 2012-2013 school year (during/after implementation of balanced literacy). Theory Balanced literacy instruction The National Reading Panel (2000) concluded that an effective reading program to teach children to read includes phonemic awareness instruction, systematic phonics instruction, fluency instruction, vocabulary instruction, and text comprehension. Based upon research the National Reading Panel (2000) concluded that a balanced approach to literacy instruction was preferred for teaching children to read. A balanced approach involves instruction in all areas of an effective reading program as determined by the National Reading Panel as well as teaching students reading and writing skills based upon their individual needs. “In balanced reading instruction, students are taught—explicitly, systematically and consistently—how to understand and use the structure of language and how to construct meaning from various texts. Students read alone, are read to, and read with others daily.” (Zygouris-Coe, 2001) A framework for literacy learning Guided reading is only one component of a balanced literacy program. A child might spend between ten to thirty minutes a day in a focused reading group RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 11 that is organized, structured, planned, and supported by the teacher. During the rest of the day, that same student will participate in whole-group, small-group, and individual activities related to wide range of reading and writing, almost all of which involve children of varying experience and abilities (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996, p.21). According to Fountas and Pinnell and the Ohio State University Literacy Collaborative there are eight instructional components that comprise a literacy framework. These eight components include: reading aloud, shared reading, guided reading, independent reading, shared writing, interactive writing, guided writing or writing workshop, and independent writing (Fountas & Pinnell,1996, p.22). Refer to figure 1.4. Ongoing assessments in the form of running records are collected as a record of student reading behaviors during guided reading instruction. “Running records are a powerful tool not only for assessing reading levels and matching children with texts but for analyzing reading behaviors for evidence of the development of independent reading strategies.” (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996, p.39) These components and the use of running records will become the basis for literacy instruction at Emerald City Elementary. The works of Marie Clay will be used as a guideline for the use of and evaluation of running records. Refer to figure 1.5 for the sample running record form which is an adaptation of the running record forms suggested by Fountas and Pinnell. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 12 Figure 1.4 Four Kinds of Reading Four Kinds of Reading Read Alouds Shared Reading Guided Reading Reading Independent Levels of Support The teacher reads aloud to the students; but both the teacher and the students think about, talk about, and respond to the text. The teacher stops briefly to demonstrate text talk or invite interaction. These pauses are intentional and planned to invite students to join in the thinking and talking about the text. The conversation is grounded in the shared text. Builds a shared repertoire of genres, authors, and specific texts that can be referred to in discussion. Enlarged text- a large-print book, a chart, a poem, or a projected text. Students and teacher read the text together. When children are emergent readers, the teacher leads the group, pointing to the words or phrases to help children follow the print. Emphasis is on enjoyment and experiencing a large number of texts together. Teacher actively supports phrasing, fluency, and other strategic actions. Students and teacher read the text together. Small group of children who are similar enough in their reading development that they can be taught together. The teacher selects and introduces a new text that is just right and offers a small bit of challenge. Children read the ENTIRE text to themselves or aloud. To sustain forward progress, children need to take part in a guided reading group between three and five days per week, reading a new book EVERY time the group meets. The children read to themselves or to partners. The teacher sets a purpose for reading. Students apply what they have learned. Students think in new ways about their reading. Students take responsibility for their own learning. Teacher provides full support for children to access the text Teacher selects text from quality literature that is above students grade and/or reading levels Children may join in but usually do not focus on features of print Skills or Strategies Taught or Reinforced Teacher provides high level of support The teacher models fluent and oral processing of text. The teacher makes specific teaching points related to the reading processes; often specific pages are revisited. Some teacher support is needed. Reader processes a new text in a way that is mostly independent. Little or no teacher support is needed for the practice portion of independent reading. The reader independently solves problems while reading for meaning. Focus is on thinking and comprehension strategies rather than reading strategies, such as the “fix up” strategies. Thinking within the text- through discussion you can help them identify important information to remember in summary form. Listening comprehension is built through daily experiences and hearing texts read aloud. Thinking beyond the text-provides opportunities to make connections, determine author’s purpose, draw from personal experiences (schema). Thinking about the text- provide opportunities to consider aspects of the writer’s craft and engage in analytical and critical thinking. Fluency- phrasing, rapid processing of text, intonation, expression, and what to do at point of difficulty. Structure and organization of different genres (i.e., multiple lines of texts per page, poems, dialogue, fiction and non-fiction). Introduction of text- point out aspects that may be new, involve them in a conversation about the text, encourage interest in the book. Reading the text- readers will independently process the entire text or a unified part of it. Students in Kindergarten or Grade 1 will usually read out loud. Discussing and revisiting the text- teacher and students participate in a brief, meaningful conversation about the text. Students may also revisit the text to clarify or locate information or to provide evidence for their thinking. Teaching for processing strategies- teacher provides a brief, explicit teaching point focused on any aspect of the reading process. Working with words (optional)- 1-2 minutes of word work that may focus a pre-planned exploration of the features of letters or how words are taken apart. Extending the understanding of the text (optional)extend the students’ understanding of the text by talking, drawing, or writing about what they have read. Students are expected to apply all of the skills and strategies listed above. Adapted from p.27 Guided Reading by Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell and p. 217, 309, 373, 329 Teaching for Comprehending and Fluency, Fountas and Pinnell RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS Figure 1.5 Running Record Form front and back 13 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS Adapted from Fountas & Pinnell 14 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 15 Developmental Reading Assessment 2 “Development of the DRA2, K-3, and DRA2, 4-8, was based on what educators and extant research literature identified as being key characteristics and behaviors of good readers.” (Pearson, 2009) The theoretical framework for the DRA2 is based upon 12 premises. Premise 1 states good readers choose reading materials to fulfill different purposes and to reflect their interests. Good readers read well-targeted text with a high level of success and accuracy. Premise 2 states good readers read for extended periods of time that are consistent with the purpose for reading. Premise 3 states good readers preview a book before reading in order to predict events, identify topics or themes, or make real-world connections by relating the content to their own experiences. Premise 4 states good readers read aloud with fluency for longer periods of time. Premise 5 states good readers are aware of and use a variety of strategies to decode words and comprehend reading materials, including previewing text, self-questioning, paraphrasing, and note-taking. Premise 6 states good readers read for meaning and understanding and are able to summarize text in their own words. Older readers should also be able to summarize what they read in writing. Premise 7 states good readers read and communicate with others using both oral and written discourse. Premise 8 states good readers can monitor and develop their reading skills. Premise 9 states good readers can read, comprehend, and interpret text on a literal level. Premise 10 states good readers can read, interpret text by making use of inferences, and make connections to personal experiences and existing knowledge. Premise 11 states good readers validate their inferences, generalizations, connection, and judgments RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 16 with information from the text, information from other sources, or personal experiences. Premise 12 states good readers reflect on what they read to determine its significance to validate its authenticity, and to understand the author’s intent (Pearson, 2009, p.7-13 ) The DRA2 system continuum for evaluating student reading behaviors aligns with the suggestions of the National Reading Panel. The student reading continuum is divided into three sections. The first section measures student reading engagement. It is used for further instruction but not as a measurement of the student’s reading level. The next section is a measure of oral reading. It measures reading miscues and fluency. To be successful in this portion the student must have an adequate reading rate as well as phrased and fluent reading. The student must also apply phonics skills and detect miscues and then make corrections. The final section of the continuum measures reading comprehension. According to the DRA2 Teacher Guide, for the student to score “independent” at a given level they must have specific scores in the oral reading and reading comprehension sections. An example of the DRA2 student reading continuum can be found in the appendix section of the final research study. Response to intervention. Language related to Response to Intervention (RTI) was written into U.S. law with the 2004 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). This law indicates that school districts are no longer required to take into consideration whether a severe discrepancy exists between a student’s achievement and his or her intellectual ability in determining eligibility for learning-disability services (International Reading Association, 2009). RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 17 School districts may choose to use scientifically research-based classroom instruction. Then if students do not respond to the classroom instruction they move to “more tailored and intensive instruction” in the form of interventions. Students who then do not make adequate progress in the hierarchal tiers of intervention are considered for evaluation for a specific learning disability (International Reading Association, 2009). According to the International Reading Association (2009) the guiding principles for Response to Intervention are: prevent problems by “optimizing language and literacy instruction”, differentiated instruction and intervention, assessment is used to drive instruction, collaboration amongst professionals, parents and students, instruction and assessment must have a systematic approach, and “all students have the right to receive instruction from well-prepared teachers.” Definition of Terms Balanced Literacy Instruction Fountas and Pinnell describe balanced literacy instruction as instruction that involves the use of four kinds of reading (read alouds, shared reading, guided reading and independent reading) as well as four kinds of writing (shared writing, interactive writing, guided writing and independent writing). Guided Reading “Guided reading is a context in which a teacher supports each reader’s development of effective reading strategies for processing novel texts at increasingly challenging levels of difficulty.” (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996, p.2) RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 18 Components of Reading Instruction The National Reading Panel has determined that phonemic awareness, systematic phonics instruction, fluency instruction, vocabulary instruction, and text comprehension instruction as the five components of effective reading instruction. Running Records “A running record is a tool for coding, scoring, and analyzing a child’s precise reading behaviors.” (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996, p.89) Developmental Reading Assessment 2 DRA2 is a reading assessment created by Pearson in which a child’s accuracy, fluency, and comprehension are monitored using leveled text. An independent reading level is found for the student. (Pearson, 2006) Research Question This study will attempt to research this topic and answer the question: Does the use of a balanced literacy model increase first grade student end of year reading achievement as measured by the Developmental Reading Assessment 2 at a rural Northeast Texas Public School? RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 19 Hypothesis It is hypothesized that the use of the balanced literacy approach to reading instruction will have a positive impact on the end of year reading levels of the first grade students. The null hypothesis used for this study will be: The use of the balanced literacy approach to reading instruction will not have a positive impact on the end of year reading levels of the first grade students. Limitations of the Study There are many limitations to this study that must be considered. The first limitation is the quality of instruction the classroom teachers receive on balanced literacy. If the teacher receives poor instruction on how to implement balanced literacy she cannot be expected to maximize the effectiveness of the model. Another limitation is that there is not a way to compare the quality and components of the guided reading lessons used during the 2011-2012 school year. We will only be able to look at the quantity of the instruction provided as opposed to the quality of instruction. During guided reading it is important to focus on the specific needs of the group you are working with. This requires an expectation of quality instruction. Improved student reading achievement is the goal of this switch to balanced literacy instruction. However, for this change to happen the teachers must implement the program with fidelity. The teachers cannot merely listen to the professional development training. They must transfer their new learning to classroom practice. Another limitation to consider is that we will be looking at data from two different sets of students. One set of data will come from the first grade students during the 2011-2012 year and the second set of data will come from the first grade students RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 20 during the 2012-2013 year. There are truly more variables between the two groups than we can completely control. Another limitation for the study to consider is the use of running records to record student reading behavior. The first grade teachers will have varying degrees of experience using running records and the miscue analysis system suggested by Fountas and Pinnell. Teachers will have to receive training and have opportunities to practice administering running records. Standardized guidelines will have to be established for the correct use of the running records. Teachers will needs to record all miscues, self-corrects, words per minute, notes of phrasing and fluency, miscue analysis, and teach point. The final limitation to consider is the spreadsheet that the teachers use to report the reading levels of their students throughout the year. Historically, the teachers at Emerald City Elementary only reported reading levels on the Appendix H. They were not required to turn in the running records along with the Appendix H. Therefore, some of the teachers inflated the scores that they reported. Then when the mid-year and end of year DRA2 was administered there was a discrepancy between the levels the students had been working at and the level they tested.. For this research study the teachers will be required to turn in the running records for their class along with the Appendix H. The reading interventionists will then verify the running records in much the same manner they verify the DRA scores at beginning, middle, and end of year. Conclusion RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 21 The Response to Intervention process used at Emerald City Elementary indicates that there is a problem with the tier 1 reading instruction in first grade. With this study I will attempt to show that balanced literacy instruction is the answer to the reading instruction problems that Emerald City Elementary faces. The theory behind balanced literacy and guided reading support the shift in tier 1 instruction that the school has planned. Once the end of year Developmental Reading Assessment 2 is administered and the data is evaluated, the school will be able to make further decisions for more instructional changes. This will be an interesting year to monitor these instructional changes. Chapter 2 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 22 Literature Review After searching the professional literature, I have decided to divide the information in the literature review into five sections. I felt that it was important to provide theory and background for effective reading instruction, balanced literacy instruction, and guided reading since that is the cornerstone of the changes to come for Emerald City Elementary. I also included the information that I found in the professional literature about Response to Intervention. Response to Intervention has shown the administration that changes must occur at Emerald City Elementary. The final section of the literature review discusses the characteristics of effective professional development. This section is important because for teachers to gain the new knowledge and then transfer it to classroom instruction they must have quality training. Effective Reading Instruction “The most fundamental responsibility of schools is teaching students to read.” (Moats, 1999) How then do we effectively teach students to read? It takes much more than having a classroom with a teacher and books. It requires an excellent reading teacher to teach children how to read. The International Reading Association issued a position statement that describes the research-based qualities of an excellent reading teacher. Excellent reading teachers believe that all students can learn to read and write and they understand how reading and writing develop. Excellent reading teachers assess individual student progress, have a variety of methods for teaching reading since they understand that no one way will work for all students, and provide students with text to read. They use flexible groups and provide strategic help as needed (International Reading Association, 2000). Effective reading teachers ground their RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 23 instruction in research-based practices. They remain current on the best ways to provide literacy instruction. Effective teachers know when they need continued professional development and training to continue to improve. Effective reading teachers follow the research that shows there are four “pillars” of an effective reading program. These pillars include: valid and reliable assessments, instructional programs and aligned materials, aligned professional development, and dynamic instructional leadership (Learning Point Associates, 2004). The second pillar, instructional programs and aligned materials, can then be further sub-divided into the five components of effective reading instruction. As stated before, these five components are: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. “There is a strong agreement that schools will succeed only when teachers have the expertise and competence needed to teach reading effectively.” (International Reading Association [The role of reading specialist: A position statement], 2000) What happens when the teachers on a campus lack the expertise or competence or the reading instruction is less than stellar? As instructional leaders of the school, the principal and other administrators play a crucial role in the implementation of an effective reading program. They provide the teachers with the professional development that they need while at the same time utilizing the reading specialist or coaches on their campus. The use of reading specialist or coaches is supported by the International Reading Association as well as the work by Lyons and Pinnell. What are the characteristics of effective reading instruction? In 2000 the National Reading Panel issued a report based upon years of scientific research that attempted to answer that question. They discovered that for reading instruction to be effective it has to include: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 24 phonemic awareness instruction, direct systematic phonics instruction, fluency instruction and practice, vocabulary instruction, and direct instruction in the use of comprehension strategies. Since the report in 2000 other researchers have taken the information from the National Reading Panel and have elaborated upon the findings (Learning Point Associates, 2004; Zygouris-Coe, et.al., 2001; Shanahan, et. al., 2010; Pressley, et. al., 2002). “These five areas were incorporated into the No Child Left Behind Act and the Reading First initiative as essential components of effective reading instruction.” (Learning Point Associates, 2004) Balanced Literacy Defined Balanced literacy is described as a balance between reading to children, reading with children, and reading by children (Zygouris-Coe, 2001). This definition aligns with the definition provided by Fountas and Pinnell that states a balanced literacy program provides for several kinds of reading and writing: reading aloud (to children), shared reading (with children), guided reading (with children), and independent reading (by children). Balanced literacy takes the four pillars of reading instruction combines it with the five components of effective reading instruction and places them in the hands of competent teachers who are aware of the needs of their students. All of the various pieces are woven together in a systematic manner to teach children to read. “In balanced reading instruction, students are taught—explicitly, systematically, and consistently—how to understand and use the structure of language and how to construct meaning from various texts.” (Zygouris-Coe, 2001) Once again this aligns with the works of Clay, Fountas, and Pinnell. Balanced literacy is not a haphazard approach to reading where students learn new skills as they come upon them naturally in text. Teachers have a plan RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 25 for the skills the students need to acquire. These skills are taught and then practiced in continuous text for real reading. Balanced literacy takes the best of the two warring camps of skill-based instruction and the whole language approach. Effective teachers realize that skills must be taught but not at the expense of rich literature that provides students with an opportunity to apply the phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension skills that they have learned (Pressley, et. al, 2002). Guided Reading Guided reading is good first teaching for all students whether they are struggling or independent. The goal of guided reading is to develop independent readers we use selfextending systems to gain meaning from the text they read (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996; Iaquinta, 2006). During the small-group guided reading lesson the teacher alters the instruction to meet the needs of the students. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to reading instruction. Fountas and Pinnell divide the guided reading lesson framework into three sections: before reading, during reading, and after reading. Before reading the teacher selects a text that will provide opportunities for students to practice the strategies they have learned. A just-right text is one that the student can read with 90% or greater accuracy. “A hard text for a reader does not provide an opportunity for smooth problem solving, and for meaning to guide the process.” (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996, p.8) The teacher begins the lesson by introducing the text. This introduction provides an opportunity for the teacher to explain key vocabulary and concepts that are important for the understanding of the story. During this introduction the students take a picture-walk as they look at and discuss the illustrations. The introduction of new text must be RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 26 well planned prior to the actual guided reading lesson. For the during reading portion of the lesson the teacher monitors and assesses the students’ reading behaviors as the students read the text. Each child reads the entire text softly to themselves as the teacher listens in and takes notes. After reading the text the teacher and students discuss the text. “The teacher selects one or two teaching points that will help the reader process more effectively.” (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996, p. 9) Fountas and Pinnell emphasize that guided reading is only a portion of a balanced literacy program. As professional development providers it is important that we communicate this idea with the first grade teachers. All four kinds of reading and writing have an important place in the balanced literacy classroom. Guided reading is critical, but it is only a part of the reading instruction. While a group is reading with the teacher at the guided reading table the other students must be “engaged in meaningful literacy.” (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996, p.53) Response to Intervention In the wake of No Child Left Behind it is imperative that we distinguish between the students who are struggling due to poor instruction and those that have a learning disability (Lyon, 2003). How do we do that? We provide students with effective early literacy instruction from qualified teachers using research-based practices. This is high-quality classroom instruction, tier 1 instruction, that all students have the right to. Teachers then observe those students as they move through the early stages of literacy development. Students likely to have reading difficulties “approach reading of words and text in a laborious manner, demonstrating difficulties linking sounds RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS (phonemes) to letters and letter patterns. Their reading is hesitant and characterized by frequent starts, stops, and mispronunciations. Comprehension of material being read is usually extremely poor.” (Lyons, 2003) Teachers use a cycle of: teach, practice, assess, teach, practice, and assess. It is during the assessment or progress monitoring phase that they observe the students to determine if any instructional changes are needed (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006). “Progress monitoring also generates diagnostic information that helps practitioners make classification and program placement decisions (e.g. moving a student from tier 1 to tier 2).” (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006) Response to Intervention is not a program rather it is a framework to help schools identify and support students with difficulties. It is not assumed that these students have permanent learning disabilities. RtI is a means for helping students when they need it for as long as they need it (International Reading Association, 2009). “Educators should therefore realize that the concept of RtI is broader than just an alternative for special education eligibility and should instead consider it an opportunity to improve overall instructional quality for all students in a coordinated special delivery system.” (Mercier Smith, et. al, 2009) The principal at Emerald City Elementary is using Response to Intervention in just that way. She is using it as an opportunity to improve the overall reading instruction for the campus. It is interesting to note that the three-tiered and four-tiered models for RtI that is commonly used (Little, 2012; Grimaldi & Robertson, 2011; Davis Bianco, 2010; Mercier Smith, et. al, 2009; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Texas Education Agency, 2008) is not 27 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 28 specified in the language of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (International Reading Association, 2009). Although, many articles published on the topic (Little, 2012; Grimaldi & Robertson, 2011; Davis Bianco, 2010; Mercier Smith, et. al, 2009; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006; Texas Education Agency, 2008) use common criteria in the range of: tier 1 supporting the needs for 80% of the student population, tier 2 supports 15 to 20% or less, and tier 3 meets the needs of 1 to 5% of the population. These percentages vary slightly from one source to another. Emerald City Elementary uses the suggested model of tier 1 for 80%, tier 2 for 15%, and tier 3 for 5% of the students. Response to Intervention requires a change in philosophy in regards to literacy instruction and intervention. The first grade teachers at Emerald City Elementary will follow in the footsteps of the schools profiled by Grimaldi and Robertson as well as Davis Bianco as they navigate through Response to Intervention. The changes in tier 1 instruction that started during the 2011-2012 school year in kindergarten will now move on to first grade for the 2012-2013 year. This is similar to the changes Sharon Davis Bianco describes for the southern New Jersey district in her paper. The teachers will be provided with professional development of best practices (balanced literacy), progress monitoring (running records), and a problem-solving approach to RtI. Effective Professional Development “We cannot validly hold teachers accountable for the inability to teach all students to read if we have not provided them with the knowledge necessary to do so.” (Pacsoe, 2010) Much has RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 29 been written about the training that should be offered in teacher preparation programs (Pimentel, 2007; Moats, 1999; Walsh, et al., 2006). But in the case of Emerald City Elementary, the first grade teachers on staff are certified teachers well past their pre-service training days. The challenge then becomes the best way to provide ongoing professional development so that it is effective and translates to improved student achievement. Since one of the limitations for this causal-comparative research study is the quality of training that the teachers receive for the implementation of balanced literacy, the first step is to determine what makes professional development effective. To effectively implement instructional practices teachers must receive training whether that is during their pre-service training or during ongoing staff development. However, not all professional development is created equally. Instructional leaders should focus on providing professional development that is effective so that there is an improvement in teacher instruction and student achievement (Pacsoe, 2010). “Researchers have made it quite clear that the whole school professional development inservice, also known as the one-shot model of professional development is not effective in improving teacher instruction or student achievement. (Lowden, 2005; McCutchen, et al., 2002; Taylor, et al., 2004)” as cited by Pascoe. Effective professional development is characterized by the following: it is linked to district goals and school improvement, aligned with teacher evaluation processes, offered during the normal school day, allows for guided practice, reflection, and mentoring; it is long term with in-class support; and the content is decided upon by the stakeholders not just teachers (Pacsoe, 2010). The professional development that will be provided for the first grade teachers of Emerald City Elementary does meet the criteria for effective professional development. It will be linked to the school goal of increased end of year reading achievement among the first grade RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 30 students. It will be aligned with the teacher evaluation processes. The series of professional development trainings will be offered during the course of the regular school day over the entire academic year. The literacy coaching model as described by Lyons and Pinnell will be used so that teachers have time for guided practice, reflection, and mentoring. The reading interventionists will serve as reading coaches for the purpose of this study. They will offer inclass support for the teachers. The content for the professional development will be decided upon by the principal, reading interventionists, and the teachers involved. Teacher knowledge and efficacy impacts the transfer of knowledge from professional development training session to actual use in the classroom. If a teacher is not confident in their acquisition of new skills they are not likely to take it back to the classroom. Then the professional development is both a waste of time and money since the desired outcome is improved student achievement. “Your responsibility as a staff developer is to help teachers improve their practice so that students learn.” (Lyons & Pinnell, 2001) The following topics will be the focus of instruction on the professional development days to help teachers improve their practice: introduction to balanced literacy; four kinds of reading and writing; implementation of guided reading; using and analyzing running records to drive instruction; the five components of effective reading instruction; and how to administer the Developmental Reading Assessment 2. A copy of the agenda for each training session as well as documentation of in-class support will be included in the appendix section of the final research study. The reading interventionists will use the constructivist principles of teaching as outlined in Lyons & Pinnell. Principles: 1) encourage active participation 2) organize small-group RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 31 discussions around common concerns 3) introduce new concepts in context 4) create a safe environment 5) develop participants’ conceptual knowledge through conversation around shared experiences 6) provide opportunities for participants to use what they know to construct new knowledge 7) look for shifts in teachers’ understanding over time 8) provide additional experiences for participants who have not yet developed the needed conceptual understanding. Summary In summation the literature reviewed makes a strong case for the use of balanced literacy instruction as the means for teaching children to gain meaning from text. The teachers implementing these instructional changes at Emerald City Elementary will need to have a working knowledge of the five components of effective reading instruction and how they work with guided reading to meet the different needs of the students in the class. The reading interventionists on the campus will use the coaching model and other steps for effective professional development as they teach the first grade teachers about balanced literacy. If my hypothesis is correct, then the positive effect of these instructional changes will be seen in the percentages of first grade students in need of tier 2 and 3 reading intervention next year. Chapter 3 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 32 Methodology Research design This causal-comparative research study will attempt to determine if the implementation of balanced literacy model which includes guided reading will have a positive effect on the end of year reading level of first grade students. The variable to be manipulated in the two comparison groups in the study will be the use of balanced literacy instruction in the first grade classrooms. The DRA2 end of year reading levels for the first grade students for the 2011-2012 school year will be compared to the end of year reading levels for the first grade students for the 2012-2013 school year. This study will attempt to identify a cause and effect relationship between balanced literacy and reading achievement scores. Because of the number of variables that exist (gender, economic status, previous reading instruction, different teachers, different classrooms) that could influence the results of the study; the statistical technique of analysis of covariance will be used (Gay, et.al, p.233). Sample All of the first grade teachers on the Emerald City Elementary campus will implement balanced literacy specifically guided reading in their classroom during the 2012-2013 academic year. Therefore, the participants for this study will be all first grade teachers for the 2012-2013 school year at Emerald City Elementary. The exact roster of first grade teachers has not been set at the time of this proposal. The principal is in the process of finalizing teaching assignments for RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 33 the 2012-2013 year. Based on current student enrollment projections for the 2012-2013 academic year, there will be 9 or 10 self-contained first grade teachers on the campus. The entire population of first grade students will be used and data will be collected on the approximately 22 students in each class. Based on enrollment projections for the 2012-2013 academic year there will be 198 to 220 first grade students on the campus. The exact number of students in each class as well as the demographics attributed to them (gender, race, economic status) will be determined once the class rosters are set by the school. Student placement within the classes will not be manipulated for this study. Typically the students at this campus are placed in classrooms heterogeneously with the same number of boys, girls, economically disadvantaged, high, low, and average students within each class. Instrumentation Fountas and Pinnell stated that the use of running records is an integral piece of reading instruction. Running records are used to document and analyze student reading behaviors for later instruction. Because of the importance attributed to the use of using running records (Clay, 1993, 2000; Fountas and Pinnell, 1996) to facilitate guided reading instruction and thus an integral piece of balanced literacy I have decided to use running records as one measurement instrument for this study. The running records will provide evidence of systematic guided reading instruction for each first grade student. The guidelines from Clay, Fountas and Pinnell for administering and using running records will be used. An example of the coding system and running record form will be included in the appendix section of this proposal. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 34 Development Reading Assessment 2 created by Pearson will be used at the beginning, middle, and end of the year data collection. The guidelines set forth in DRA2 Teacher Guide will be strictly adhered to. This measurement system is currently in use at Emerald City Elementary as part of their standard data collection protocol for all students kindergarten through third grade. DRA K-3 assesses student performance in the following areas of reading proficiency: reading engagement, oral reading fluency, and comprehension. The selections of these target skill areas and the methods used to assess them are based on current research in reading from sources such as the National Reading Panel Report (2000) and Reading for Understanding (Rand Education, 2002). (Beaver, 2006) For DRA2 students read a book at their anticipated independent reading level as determined by running records during classroom guided reading instruction. The assessment measures the characteristics and behaviors of good readers. The DRA2 “scaffolds primary students as they move through the various stages of learning to read.” (Beaver, 2006) The student’s reading engagement, oral reading fluency, and reading comprehension are then measured using the DRA2 Continuum. Procedural details Student instructional and independent reading levels will be measured using Running Records (Clay, 1993,2000; Fountas and Pinnell,1996) at regular intervals (to be determined) throughout the academic year. These running records will include the title and level of the text RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 35 read, percent accuracy, MSV coding for errors, number of errors, number of self-corrects, teach point, and praise point. I have chosen to use the district created timeline for reading level measurements. This timeline will be distributed to the teachers prior to the first day of school. This first method of data collection will be completed by the classroom teachers. Each teacher will collect student instructional reading levels via running records for the students in their class during guided reading groups. This student data will be turned in to the campus principal and the two reading interventionists on the Appendix H data collection sheet (Fountas and Pinnell, 1996). For this research study I will serve as both a reading interventionist and researcher. Reading levels will be reported in both the lettering system as used by Fountas and Pinnell as well as the numbering system as used by DRA2. Refer to figure 1.6 . Figure 1.6 Reading Level Conversion Chart Fountas and Pinnell to DRA Reading Level Conversion Chart Exit Levels End of kindergarten End of 1st Grade End of 2nd Grade End of 3rd Grade Fountas and Pinnell A B C Developmental Reading Assessment 1 2 3 AND 4 D E F G H I 6 8 10 12 14 16 J K L M N O P Q 18 20 24 28 30 34 38 40 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 36 The second method of data collection will be the Developmental Reading Assessment 2 (Beaver, 2006) which will be administered to each first grade student by the teachers and verified by the reading interventionists at the beginning, middle, and end of the year. The numbered system for reading levels as assigned by the Developmental Reading Assessment 2 system will be used. The DRA2 system recommends an end of year reading level for first grade students of independent 16. This information will then be logged into a Reading Level spreadsheet that is used for the Response to Intervention process. The teacher will be required to turn in lesson plans documenting the use of balanced literacy. The teacher will also be required to submit guided reading lesson plans for each of the reading groups she sees. These guided reading plans should indicate the number of minutes each day that the students spend in small group instruction, the focus of the lesson, the reading level of the group, as well as the students in the group. Validity and reliability “Validity refers to the degree to which a test measures what it is supposed to measure and, consequently, permits appropriate interpretation of scores.” (Gay, et al., 2012) The information in the DRA2 Technical Manual indicates that the DRA2 was measured for contentrelated validity, criterion-related validity, and construct validity. “Content validity was built into the DRA and DRA2 assessments during the development process. Texts are authentic, and the student is asked to respond to the text in ways that are appropriate for the genre.” (Pearson, 2009) The DRA2 Technical Manual reports correlational coefficients using Spearman’s Rho ranging from .60 to .76 for student reading performance on DRA2 and GORT-4, DORF, and Gates MacGinitie Reading tests. In summation of the technical report provided by DRA2, the RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 37 data shows “the results presented indicate that the DRA2 is a valid measure that can accurately measure students’ oral reading fluency and comprehension level.” (Pearson, 2009) “Reliability is the degree to which a test consistently measures whatever it is measuring. The more reliable a test is, the more confidence we can have that the scores obtained from the test are essentially the same scores that would be obtained if the test were readministered to the same test takers at another time or by a different person.” (Gay, et al., 2012) Four methods were used to determine the reliability of the DRA2. These include internal consistency, parallel equivalency reliability, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability (Pearson, 2009). Triangulation of the multiple forms of reliability analyses that were conducted shows that the DRA2 is a reliable measure in that it produces stable, consistent results over time, different raters, and different samples of work or content. Specifically, it demonstrates moderate to high internal consistency reliability, parallel-equivalency reliability, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability. (Pearson, 2009, p.34) The technical manual notes that it is imperative that raters follow the administration and scoring guidelines provided in the DRA2 teacher guides and kits (Pearson, 2009). Because of the validity and reliability attributed to the DRA2, it is expected that the data collected at the beginning, middle, and end of year using the assessment will also be valid and reliable. The teachers administering the assessments will follow the guidelines established in the teacher manual. Likewise the reading interventionists will verifier the assessments using the same criteria. This process of teachers testing and interventionists verifying will provide a checks and balances system which will add the reliability of the scores. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 38 Data analysis The data in this study will be analyzed using inferential statistics. “Inferential statistics help researchers to know whether they can generalize to a population of individuals based on information obtained from a limited number of research participants.” (Gay, et. al, p.341) Because of the number of variables that cannot be manipulated analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) will be used. “Analysis of covariance is a statistical technique used to adjust initial group differences on variables used in causal-comparative and experimental studies (Gay, et. al, p.233). The end of year reading levels as determined by the DRA2 for students in first grade for the 2011-2012 school year will be compared to the end of year reading levels as determined by the DRA2 for the first grade students for the 2012-2013 school year. Conclusion As public schools in Texas implement Response to Intervention procedures, they will have to use the data to evaluate the quality of instruction or intervention they are providing at each tier. It will become necessary to make changes in tier 1 classroom instruction to reduce the number of students in need of interventions at tiers 2 and 3. It is hypothesized that this causalcomparative study will show that the use of research-based best practices such as balanced literacy and guided reading in regular classroom instruction will have a positive impact on the end of year reading levels for first grade students. Hopefully the data that is collected for this study will help to show teachers that the quality of the instruction you provide has a direct impact on student achievement. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS References Beaver, Joetta M. (2006). Developmental Reading Assessment 2 K-3 Teacher Guide. Saddle River, New Jersey: Heinemann. Beaver, Joetta M. (2006). Developmental Reading Assessment 2. [Benchmark Reading Assessment System]. Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. Clay, M.M. (1993). An observation survey of early literacy achievement. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Clay. M.M. (2000). Running records for classrooms teachers. Rosedale, North Shore, New Zealand: Heinemann Education. Davis Bianco, S. (2010). Improving student outcomes: Data-driven instruction and fidelity of implementation in a response to intervention (RTI) model. TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus, 6(5) Article 1. Retrieved from http://escholarship.bc.edu/education/tecplus/vol6/iss5/art1. Elsea, B. (2001). Increasing students’ reading readiness skills through the use of balanced literacy program. (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from Educational Resources Information Center. CS 104 426. Fitzgerald, J. and Cunningham, J. W. (2002). Balance in teaching reading: An instructional approach based on a particular epistemological outlook. Reading & Writing Quarterly. 18, 353-364, doi:10.1080/07487630290061881. Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (1996). Guided reading: Good first teaching for all children. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. 39 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 40 Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell,G.S. (2006). Teaching for comprehending and fluency. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Fuchs, D. and Fuchs, L.S. (2006). Introduction to response to intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41(1), 93-99. doi:10.1598/RRQ.41.14 Gay, L.R., Mills, G.E., and Airasian, P. (2012) Educational research competencies for analysis and applications. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C.M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Linan-Thompson, S., and Tilly, W.D. (2008). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to Intervention and multi-tier intervention for reading in the primary grades. A practice guide. (NCEE 2009-4045). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/ publications/practiceguides/. Grimaldi, S. and Robertson, D.A. (2011). One district’s RTI model and IRA’s guiding principles: The roads converge. New England Reading Association Journal, 47(1), 18-26. Iaquinta, A. (2006, June). Guided reading: A research-based response to the challenges of early reading instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal. 33 (6), 413-418, doi: 10.1007/s10643-006-0074-2. International Reading Association. (2000). Excellent reading teachers: A position statement of the International Reading Association. Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved from http://www.reading.org/Libraries/Position_Statements_and_Resolutions/ps1041_excellen t_1.pdf RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 41 International Reading Association. (2009). Response to intervention: Guiding principles for educators from the International Reading Association. Newark, DE:Author International Reading Association. (2000). Teaching all children to read: The roles of the reading specialist a position statement of the International Reading Association. Newark. DE: Author. Retrieved from http://www.reading.org/Libraries/Position_Statements_and_Resolutions/ps1040_specialis t.sflb.ashx International Reading Association. (2002). What is evidence-based reading instruction? (Position Statement). Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved from http://reading.org/Libraries/Position_Statements_and_Resolutions/ps1055_evidence_base d.sflb.ashx Learning Point Associates. (2004). A closer look at the five essential components of effective reading instruction: A review of scientifically based reading research for teachers. Naperville, IL: Author Little, Mary E. (2012). Action research and response to intervention: Bridging the discourse divide. The Educational Forum, 76, 69-80. doi:10.1080/00131725.2012.629286 Lowden, C. (2005). Evaluating the impact of professional development. The Journal of Research in Professional Learning. Lyon, G. Reid. (2003). Reading disabilities: Why do some children have difficulty learning to read? What can be done about it? Perspectives, 29(2) Lyons, Carol A. and Pinnell, Gay Su. (2001). Systems for change in literacy education. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Mercier Smith, J.L., Fien, H., Basaraba, D., and Travers, P. (2009). Planning, evaluating, and improving tiers of support in beginning reading. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 41(5), 16-22. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 42 Moats, L.C. (1999). Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. Washington, D.C.: American Federation of Teachers National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruciton. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 1070110, 115 Stat. 1425 (2002). Pascoe, S. E. (2010, July). Best practices of effective professional development training for K-3 reading teachers. (unpublished master’s thesis). Northern Michigan University. Michigan. Pearson. (2009). K-8 Technical manual developmental reading assessment. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson. Retrieved from http://s7ondemand7.scene7.com/s7ondemand/brochure/flash_brochure.jsp?company=Pea rsonEducation&sku=DRA2_TechMan&vc=instanceName=Pearson&config=DRA2_Tec hMan&zoomwidth=975&zoomheight=750 Pimentel, S. (2007). Teaching reading well: A synthesis of the International Reading Association’s research on teacher preparation for reading instruction. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Pressley, M., Mohan, M., Raphael, L.M., and Fingeret, L. (2007). How does Bennett Woods Elementary School produce such high reading and writing achievement?. Journal of Educational Psychology. 99 (2), 221–240, doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.221. Pressley, M., Roehrig, A., Bogner, K., Raphael, L.M., and Dolezal, S. (2002, January). Balanced literacy instruction. Focus on Exceptional Children. 34 (5), 1-15. WN: 0200103212001 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS 43 Shanahan, T., Callison,K., Carriere, C., Duke, N.K., Pearson, P.D., Schatschneider, C., & Torgensen, J. (2010). Improving reading comprehension kindergarten through 3rd grade: A practice guide (NCEE 2010-4038). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from whatworks.ed.gov/publications/practiceguides. Texas Education Agency. (2008). 2008-2009 Response to intervention guidance. Austin, TX: Author. Retrieved from http://www.tea.state.tx.us/index2.aspx?id=5817 Walsh, K., Glaser, D., & Wilcox, D.D. (2006). What education schools aren’t teaching about reading and what elementary teachers aren’t learning. Washington. DC: National Council on Teacher Quality. Zygouris-Coe, V. (2001). Balanced reading instruction in K-3 classrooms. Florida Literacy and Reading Excellence (FLaRE) Center, University of Central Florida College of Education. Retrieved from http://flare.ucf.edu. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS Appendix A 44 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BALANCED LITERACY READING LEVELS Appendix B 45