Individual Report on the International Covenant on Civil and Political

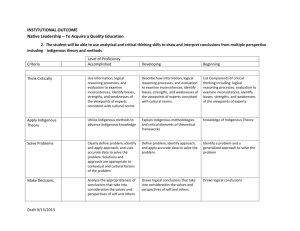

advertisement