China`s Cultural Revolution - The University of Tennessee at

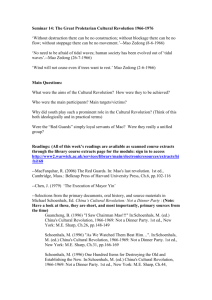

advertisement

China’s Cultural Revolution AP World History Parker T. Jarnigan This lesson is designed to give students access to new perspectives on the changing nature of the Chinese revolutions of the 20th century, as well as facilitate the development of reading, listening, speaking, and analyzing skills. As such, this lesson fulfills content and skill goals required by the Tennessee Department of Education’s social studies curriculum and the College Board’s AP World History framework. The majority of the lesson will be spent discussing the readings in partners. Learning Standards Tennessee World History Standard W. 59 – Analyze the Chinese Civil War, the rise of Mao Zedong, and the triumph of the Communist Revolution in China AP World Central Concept 6.3 – New Conceptualizations of Global Economy, Society, and Culture Time Required This lesson will take one 50 minute class period, as well as time outside of class for students to read assigned materials prior to the lesson. Student Objectives SWBAT describe the events leading up to the Cultural Revolution in China SWBAT assess the effectiveness of the Cultural Revolution. SWBAT analyze the results of the Cultural Revolution Procedures, overview 10 minutes of teacher lecture 15 minutes of partner discussion 15 minutes of group sharing 10 minutes of individual student written response Procedures, detailed First, the Teacher should teach this lesson at some point after having taught lessons on the fall of the Qing, the establishment of the Republic, and the Chinese Civil War. The day before this lesson, the Teacher should hand out one of two readings to all students, splitting up the readings so that roughly half the class reads one document, and half the class reads the other. The first is a well-known short story by the Chinese Communist author Cao Ming, “A Native of Yan-an.” In it, the peasant Granny Wu is used as a device to represent the virtue of Mao Zedong’s idealized farmer versus the nationalist opposition. In this particular excerpt, students will read of Granny Wu’s personal transformation to a more revolutionary mindset as a result of her chance encounter with Chairman Mao. The story is set in 1937, in the midst of the Chinese Civil War, but it was written and published in 1947, just a few years before the victory of the Communists. The second reading is an interview transcription with Dr. Juefei Wang, taken from the journal Social Education. Dr. Wang is a Professor Emeritus at University of Vermont and Program Director for the Freeman Foundation, a private group dedicated to strengthening relationships between the US and East Asian countries. In the interview, Dr. Wang describes his personal experiences as a teenager growing up during the height of the Cultural Revolution. Specifically, Dr. Wang details what happened when the antieducation, anti-four olds forces of the Cultural Revolution took root in his junior high school. The day before the lesson, when the teacher distributes the two readings, the Teacher should use their judgment as to whether to assign any short task or questions associated with the readings in order to ensure that students read. This is not necessary for the lesson, but the decision should be made based on Teacher knowledge of students as well as the standard class procedure established by the Teacher. Students should bring their copies of the readings with them to reference in class the day of the lesson. First thing day of the lesson, the teacher should introduce the day’s lesson topic and learning objectives and then spend about 10 minutes to remind students of previous content and set the context for studying the Cultural Revolution. This should include a very brief discussion of the results of the fall of the Qing, the major conflicts of the Chinese Civil War before and after WWII, and the victory of the Communists in 1949. The teacher should then give students an overview of the basics of the Cultural Revolution, using either PowerPoint and lecture or just oral description. The Teacher should focus on detailing when the Cultural Revolution began and how long it lasted, the role of Mao in dictating the course of the Revolution, a comparison of the legacies of the First Five Year Plan and the Great Leap Forward in shaping the Cultural Revolution, and a description of how Mao’s personality cult grew in the 1950s and 60s. The Teacher should point out that the Cultural Revolution was initially the project of Chinese youth inspired to destruction by Mao’s “little red book.” Finally, the Teacher should use one or two anecdotes and some statistics to give students an idea of the scope of the impact of the Cultural Revolution. Altogether, this portion of the lesson should take no more than 10 minutes. Fitting all of this into 10 minutes will be easier if the class has had lessons on the Chinese Civil War just prior to this lesson on the Cultural Revolution. After this brief discussion, the Teacher should split the class up into pairs, with each pair having one student that read either document. In the case of odd numbers or a student that was absent the day readings were assigned, the Teacher can make a few odd groups, just so long as each group has someone that read each article. The Teacher should first instruct the pairs/groups to share with one another as to the details of the story they read. Specifically, they should share with their partners 1) Who are the subjects of the piece? 2) What is the historical time period documented in the piece? 3) What is the social position of the main subject in the piece? 4) How does the main subject interact with Mao? 5) How do the words/actions of Mao affect the subject These prompts should be on the board/projector screen during discussion. The Teacher can and should add to these suggestions based on feedback gathered while floating and monitoring pair discussion of the documents. The Teacher should encourage the students to reflect with one another as to how the stories compare and students should conjecture as to what accounts for the differences in the accounts. This pair sharing portion of the lesson should take about 15 minutes. After the pair discussion dies down, or after 15 minutes has expired, the Teacher should bring the class together for large group discussion. This discussion can take a variety of forms and directions based on Teacher judgment, but it should at least be focused around answering one major question: why is the experience of Granny Wu different than that of Dr. Wang, and what does this tell us about how China has changed from WWII to the Cultural Revolution? The Teacher might start by asking students to volunteer simple differences they observed in the documents, or the Teacher could call on students to answer some of the above questions for each document. Whatever choice, the Teacher should remind students that the fictional account of Granny Wu was created in 1947, whereas Dr. Wang describes his experiences immediately before and after the summer of 1966, and then guide discussion toward the overarching question of how these two different stories reflect change over time as China transitioned from a fractured country to one led by a megalomaniac leader like Mao Zedong. Including time for both discussion and questions from the students, this portion of the lesson should take about 15 minutes. To close out the lesson, the Teacher should reveal a short writing prompt that students will work on individually and turn in at the end of class. This deliverable will be the primary means that the Teacher assesses student attainment of the objectives. The prompt can vary, but it should refocus the students to the overarching question dealing with change across time as evidenced by the documents. The prompt might say Based on the two documents, answer the following question: How had Mao’s vision for China changed from 1947 to 1966, and to what extent can this vision be said to be a success? Students should write their short responses, probably in the form of long paragraphs, in class and turn them in at the bell. Alternatively, this may be assigned as homework if time runs short due to vigorous discussion. Evaluation The Teacher will use the materials created by students in class as the primary means of assessing the strength and success of the lesson in accomplishing the stated objectives. Success on the objectives will be exemplified by a student response that makes at least one clear, defensible, falsifiable claim about the experience of the Cultural Revolution as a manifestation of Mao’s vision for China. Student handouts The Teacher should prepare copies of the two readings for students, enough for half of students to have one and half to have the other. The Cao Ming story is available in several source readers and can be found online. The interview with Dr. Wang is behind a paywall available to subscribers of Social Education and members of the National Council for the Social Studies. Resources Masalski, Kathleen Woods. “Juefei’s Story (Interview).” Social Education, 74, no. 1 (2010): 37-41. [Ideally, this source would be reformatted with the sidebars, teacher questions, and activities from the original periodical omitted for students.] Ming, Cao. “A Native of Yan’an.” In The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Volume II, 5th ed., edited by Alfred J. Andrea and James H. Overfield, 461-465. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.