Case study 12.1: Reducing Sulphur Dioxide

advertisement

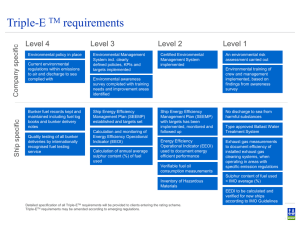

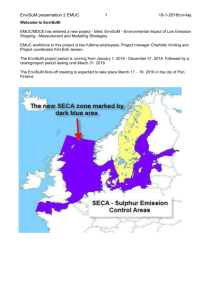

Case study 12.1: Reducing Sulphur Dioxide emissions from shipping Sulphur dioxide (SO2) is a pollutant that is toxic to the health of human, animals and plants and is the main source of acid rain. Traditionally, the majority of SO2 emissions have come from the burning of fossil fuels in power stations and manufacturing plants. However, the combined effect of legislation and a switch away from coal to gas has significantly reduced the quantity of SO2 in the atmosphere from these sources: in the UK, for example, SO2 emissions have fallen by 93.8 per cent between 1970 and 2013 according to the UK’s Department of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Consequently, following cuts in shore-based SO2 emissions, shipping has become the main source of SO2 in the atmosphere. Globally, pollution from shipping is regulated by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) through Annex VI of its International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL). The IMO has steadily been tightening the requirements of MARPOL Annexe VI and the EU has aligned its own legislation with IMO requirements. On January 1 2015, Directive 2012/33/EU came into force: this sets a limit on sulphur content in fuel of no more than 0.1 per cent, down from one per cent, in the most ecologically vulnerable marine areas, also known as Sulphur Emission Control Areas (SECAs), which in the EU means the Baltic and the North Sea, including the English Channel. In less fragile ecological areas, the maximum sulphur content will be cut from 3.5 per cent to 0.5 per cent by 2020. This compares to a 0.001 per cent limit on the sulphur content of fuel for lorries and cars. Shipping companies have three ways in which they can comply with the 0.1 per cent sulphur content limit, each of which increases costs. Option one is to switch to Marine Gas Oil (MGO), a fuel which satisfies the new limits, from Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) which satisfies the previous one per cent for SECA areas. However, MGO can be up to 50-60 per cent more expensive than HFO. Given that, as a rule of thumb, fuel costs account for about one third of the operating costs of ferries and short sea shipping, this could result in fare and tariff increases of approximately 15 per cent being passed onto freight and passenger customers. Moreover, switching to MGO would increase demand and could push up its price even more. In the longer term, if refineries adapt to produce more MGO, supplies of other fuels such as diesel could fall, resulting in higher prices for these fuels. Option two involves the use of alternative fuels such as LNG or methanol. However, this is only suitable for new ships as retrofitting existing ships is too expensive. Furthermore, this option requires a more complete LNG infrastructure than currently exists. The third option is to fit abatement technology, notably scrubbers, which will enable ships to continue to use HFO by cleaning exhaust emissions so that they comply with the 0.1 per cent limit. This technology is expensive and takes up a great deal of space: it has to be adapted individually to each ship and is not suitable for all vessels. The cost of fitting such scrubbers ranges from €4 -12 mn, depending on the size of the ship. Danish operator, DFDS, has adopted this technology for many of its ships and is spending €100 mn to retrofit up to 21 of its vessels. DFDS has also received funding from the EU to partially offset some of this additional cost. The actual consequences of the 0.1 per cent sulphur limit are unknown at the time of the entry onto force of the legislation but the following possibilities have been raised, largely by the shipping industry itself. Whatever method of compliance is chosen, operating costs of shipping companies will increase and these increases will be passed onto freight and passenger customers. Maersk Line, the world’s largest container shipping group, has estimated fuel switching would cost it an extra €200 mn per year and P&O Ferries claims it will cost it an additional £30 mn a year, extra costs which will fall disproportionately on longer routes. On the other hand, UK-based Red Funnel Ferries claims to have been using low sulphur fuel for many years but to have remained competitive through efficiency improvements. Given the low margins and highly competitive nature of the industry, some routes may be withdrawn altogether or the frequency of services on some freight and passenger services may decrease. P&O Ferries have warned that some of its longer distance North Sea routes may be vulnerable. In September 2014, DFDS closed the freight passenger service between Esbjerg in Denmark and Harwich in the UK, blaming the new sulphur emission regulations as the final straw. The route had been struggling for some time with low freight volumes and competition from low cost airlines. Initiatives such as slow steaming to save fuel and combining freight and passenger services had already been introduced, but additional savings to compensate for the estimated £2 mn increase in the fuel bill on this route were deemed impractical. The regulations will make road transport relatively cheaper and, in certain circumstances and locations, could result in a shift away from shipping to road, perhaps by-passing sea transport altogether when geography allows or encouraging customers to travel further to and from embarkation and disembarkation points to offset some of the additional costs of maritime transport. Any such modal shift will increase congestion on Europe’s roads and air pollution from road transport. The implementation of the directive, and hence its impact, remains unclear at the time of its entry into force. There is some confusion over its enforcement: each member state, for example, is responsible for deciding how to determine compliance with the directive, its enforcement and the penalties for non-compliance, even leading to some speculation that some shipping lines may find it cheaper to pay fines for non-compliance than to make the necessary adjustments to meet the 0.1% target. Case questions 1. Changes to the limits on the sulphur content of fuel for maritime purposes in the EU stemmed from MARPOL Annex VI - the main anti-pollution policy of the IMO. What does this tell us about the nature of environmental problems and their governance? 2. Who are the main beneficiaries of Directive 2012/33/EU? 3. At the time of writing, Directive 2012/33/EU had only just come into force and analysis of its consequences is purely speculative. Have these consequences come to pass? What have been the main consequences for Europe’s shipping industry? What other consequences have there been? 4. Does Directive 2012/33/EU fulfil the main principles of EU environmental policy (see Box 12.3)? If so, how? If not, why not? 5. How does Directive 2012/33/EU fit into the debate about ecological modernisation?