New Historical Edition Critical+Rationale

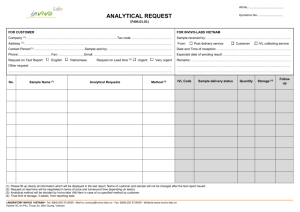

advertisement

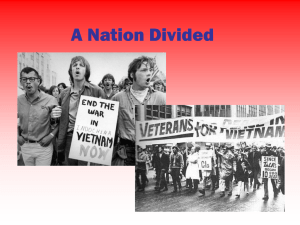

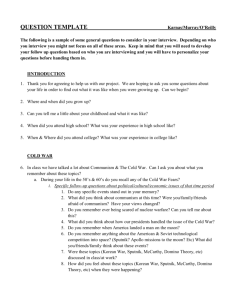

Critical Rationale In order to facilitate a thorough exploration for our New Historicism edition of Going After Cacciato, we have done considerable research into the scholarly or academic criticism aimed at the novel. Our goal with this New Historicist edition of Going After Cacciato is to “combat empty formalism by pulling historical considerations to the center stage of literary analysis” (Veeser, xi). There are several engaging debates surrounding the text itself, as well as its effect within the larger socio-historical context of the Vietnam War era, which can also be applied to contemporary issues. As editors, our principal focus was the psychological issues of soldier drug use in the theater of war, PTSD being diagnosed for the first time in Vietnam veterans, and the state of the American psyche during the war years. As such, the primary scholarly or academic articles we have included assist in placing Going After Cacciato within that somewhat narrower scope. The journal article we decided to include expands on Vietnam era literature by stating, “War strips away the thin veneer applied slap-dash by the institutions of society”, and as such “readers find in this literature answers to their questions, and as a result they are empowered to face the issues that affect their lives and their future” (Johannessen, 175). While some first time readers may feel that Going After Cacciato leaves one with more questions than answers, Johannessen’s implication of the veil surrounding society’s larger, intangible institutions is explored by Berlin’s character throughout the novel. Questions of bravery, cowardice, and myriad other elusive and fluid qualities, are considered either directly or indirectly by the characters at various points in the text, many of which receive no real answer but allow the reader to reflect on their own perspectives and reach their own conclusions. One of the most compelling aspects of Going After Cacciato is the assertion that the land is in fact Paul Berlin’s, and indeed the entire American military’s, enemy. In order to explore this psychological tension, we have included an article that specifically discusses the province used as the initial setting by O’Brien in Going After Cacciato, Quang Ngai, and its relationship to the American military forces there. The author ends with the claim that the setting in Vietnam “stands not only on dangerous ground but also on terrain that recalls a shameful history” (Golubuff, 57). Supplemental scholarly discourses have also addressed the fact that Paul Berlin’s part in the fragging of Sydney Martin, and subsequent feelings of shame, may have triggered his break from reality. Moreover, this theme of “dangerous ground” and “shameful history” could reasonably be applied to the current military situation in Iraq and Afghanistan. An additional scholarly source we included discusses how “the special conditions of Vietnam intensified the vulnerability among the ill-prepared participants of the war” (Herzog, 89). Further, that it’s “fragmentation, complexity, and illogic presents special problems” both for the soldiers who fought in it, and the authors that try to make sense of it in their writing (Herzog, 88). The author of another article that was pertinent to our psychological analysis of Going After Cacciato begins by asking, “If reality becomes surrealistic, what must fiction do to become realistic?” (Saltzman, 32). He goes on to describe the novel as a “fictional odyssey [that] represents the mind’s reflex reaction against the seeming finality of the facts of war” (Saltzman, 35). These two articles work well together to explain and explore further the fact that the Vietnam War was unlike any war before, and consequently, any of the previously held notions of war that are passed down from generation to generation via American culture were no longer viable for the experiences of Vietnam Veterans. Despite the fact that Paul Berlin’s response to his experiences in the Vietnam War may be on the extreme side, there can be no doubt that the character did this as a way to cope with a multitude of mental traumas beyond the scope of any he may have previously endured or have been prepared for as an enculturated American, i.e. death, destruction, etc. The final scholarly article we chose to include supplements the previous four by exploring how “the literary dislocation in Berlin’s tale becomes a metaphor for the overwhelming dislocations associated with Vietnam” (Raymond, 103). The authors concludes his investigation by stating “Tim O’Brien seems to believe that the atrocities of the Vietnam War were a reflection on the American culture and that the most effective way to deal with the nightmares of Vietnam…[is to] experience them” (Raymond, 104). While that statement may be a bit of a leap, Raymond cannot truly know O’Brien’s motives in writing, the notion that expressive acts are embedded in society’s material and cultural practices is one of the major assumptions of New Historicism (Veeser, xi). The diction used by these authors to express the story of Going After Cacciato as well as the experiences of Vietnam War veterans exemplifies the apparent psychological discord, felt by soldiers and civilians alike, of the time: dangerous, shameful, fragmentation, complexity, illogic, surrealistic, overwhelming, atrocities. These articles represent a segment of the scholarly or academic criticism with regards to the psychological impact of the Vietnam war that support our New Historical/Cultural reading of Going After Cacciato.

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)