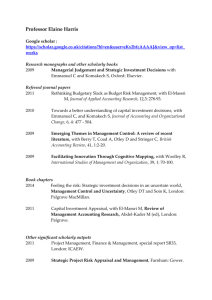

You have been selected as a member of this Society for

advertisement

In his autobiography entitled “Naturalist” written in 1994 at the age of 64, Edward O. Wilson shares his personal insights on a variety of topics, many of which address the relationship between the scholar and his mentor, his student, and his subject. These excerpts are intended to provide inspiration and motivation, or a point of departure for discussion or dispute, or a model by which research may be pursued, or simply provoke contemplation. Even though he addresses science and scientists specifically, his observations may be generalized to intellectual pursuits of all sorts by scholars in all disciplines. …. “Keep ever in mind Longfellow’s invocation: The heights by great men reached and kept, were not attained by sudden flight; But they, while their companions slept, were toiling upward in the night.” p. 74. “Adults forget the depths of languor into which the adolescent mind descends with ease. They are prone to undervalue the mental growth that occurs during daydreaming and aimless wandering.” p. 86 “What counts heavily in the shaping of a scholar is the accessibility and approval of the faculty. What is truly decisive, however, is the desire and ability of the student. Otherwise, failure awaits regardless of the learning environment, and no excuse can be made for it. If you are a lousy hunter, the woods are always empty.” p. 106 “The several best teachers of my life… have been those who told me that my very best was not yet good enough.” p. 109 “….as Alfred North Whitehead once said of scholars generally, I did not discover in order to learn; I learned in order to discover. My private pleasure was now tinged with social value. I came to routinely ask: What have I acquired in my studies that is new not just for me but for science as a whole?” p. 114 “The advise I give to students… is to move laterally and up and down and peer all around. If you have the will, there is a discipline in which you can succeed. Look for the ones still thinly populated, where fine differences in raw ability matter less. Be a hunter and explorer, not a problem solver. “ p. 123 On page 145, Wilson describes what happened at the first dinner to welcome newly selected members of Harvard’s elite Society of Fellows. This statement, composed by Abbott Lawrence Lowell, former president of Harvard and founder of the Society, was read. You have been selected as a member of this Society for your personal prospect of achievement in your chosen field, and your promise of notable contribution to knowledge and thought. That promise you must redeem with your whole intellectual and moral force…. You will seek not a near, but a distant, objective, and you will not be satisfied with what you have done. All that you may achieve or discover you will regard as a fragment of a larger pattern, which from his separate approach every true scholar is striving to descry. p. 145 On page 171, Wilson says “I am a neophile, an inordinate lover of the new, of diversity for its own sake.” He then writes in italics his prayer: “Take me, Lord, to an unexplored planet teeming with new life forms. Put me at the edge of a virgin swampland dotted with hummocks of high ground, let me saunter at my own pace across it and up the nearest mountain ridge, in due course to cross over to the far slope in search of more distant swamps, grasslands, and ranges. Let me be the Carolus Linneaus of this world, bearing no more than specimen boxes, botanical canister, hand lens, notebooks, and allow me not years but centuries of time. And should I somehow tire of the land, let me embark on the sea in search of new islands and archipelagoes. Let me go alone, at least for a while, and I will report to You and loved ones at intervals and I will publish reports on my discoveries for colleagues. For if it was You who gave me this spirit, then devise the appropriate reward for its virtuous use. “ p. 171 “Nature first, then theory. Or, better, Nature and theory closely intertwined while you throw all your intellectual capacity at the subject. Love the subject for itself at first, then strain for general explanations, and, with good fortune, discoveries will follow. If they don’t, the love and pleasure of the work will have been enough.” p. 191 On page 268, Wilson observes most students “accept low risk projects, those new enough to generate significant results but close enough to preexisting knowledge and proven techniques to be practicable.” On page 205 he observes that a scholar “if truly creative… does not always hug the coast. He gambles repeatedly on risky projects, stays alert and aggressive, ready to move whenever a long shot shows a hint of promise.” In confessing his motivation, Wilson writes “I just wanted to be the first to find something, anything, the more important the better, but something as often as possible, to own it a little while before relinquishing it to others. I confess that to the degree I was insecure, I was also ambitious. I hungered for the recognition and support that discovery in science brings. To make this admission does not embarrass me now as it would have when I was young. All the scientists I know share a desire for fair recognition of their work. Acknowledgment is their silver and gold, and why they are careful to grant deserved priority to others while so jealously guarding their own. New knowledge is not science until it is made social. The scientific culture can be defined as new verifiable knowledge secured and distributed with fair credit meticulously given.” p. 210 Scholars “are divided into two categories: those who do scholarly work in order to be a success in life, and those who become a success in life in order to do scholarly work. It is the latter who stay active in research for a lifetime.” p. 210 One has to “crack eggs to make an omelet.” p. 223 “The ground between scholarly work and political engagement is treacherous. Speak too forcefully….and others regard you as an ideologue; speak to softly, and you duck a moral responsibility.” p. 356. “Many kinds of spiders, when crowded or short of food, prepare to emigrate by standing in exposed places on leaves and twigs and letting out threads of silk into the wind. As the strand lengthens, the drag increases, until the spiders have difficulty holding themselves in place. Finally they let go, allowing the wind on the strands to pull them up and away. With luck they come down again on land, and best of all in some place like a distant island with few other spiders and an abundance of prey. Those that hit water instead soon become fish food.” p. 276.