To be submitted to VOX EU Capital Control Measures: A New

advertisement

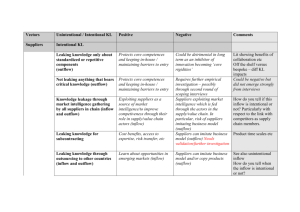

To be submitted to VOX EU Capital Control Measures: A New Dataset Andrés Fernández, Michael W. Klein, Alessandro Rebucci, Martin Schindler and Martín Uribe March 6, 2015 The Great Recession has spurred a reconsideration of the appropriate role of capital controls. The prevailing view among economists in the 1990s was reflected in the title of Rudiger Dornbusch’s 1998 article “Capital Controls: An Idea Whose Time is Gone.” But attitudes began to shift in response to the economic crises in the late 1990s. More recently, IMF staff studies and policy papers have shown greater acceptance of the use of capital controls as part of a country’s “policy toolkit” under certain circumstances, a shift that The Economist magazine dubbed “The Reformation.”1 Other prominent calls for a greater role for capital controls include those by Jeanne, Subramanian and Williamson (2012) and Rey (2013). Some of these policy prescriptions are consistent with a new branch of theoretical research in which capital controls contribute to financial stability and macroeconomic management. 2 But these theoretical works stand in contrast to a large number of empirical analyses that emphasize the ineffectiveness and potential costs of capital controls.3 See, for example, Ostry, Ghosh, Chamon, and Qureshi (2011). The Economist article appeared in the April 7, 2011 issue. 1 For just a few examples, see Jeanne and Korinek (2010), Javier Bianchi (2011), and Benigno, Chen, Otrok, Rebucci and Young (2013, 2014). 2 3 See, for example, Forbes (2007), Klein (2013), and Klein and Shambaugh (2013). The evolving debate on capital controls highlights the importance of careful empirical analyses of these policies. One challenge facing researchers in this area is the availability of indicators of capital controls. We have constructed a new data set that reports the presence or absence of de jure capital controls, on an annual basis, for 100 countries over the period 1995 to 2013.4 Like other de jure capital control panel data sets, ours is based on information in the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER).5 One contribution of our work is that we have developed a specific set of rules for coding the narrative reports in the AREAER, which we present in a technical appendix to our paper. A distinguishing and important feature of our data set is its disaggregation of data series down to the level of individual types of transactions between residents and non-residents, allowing for the construction of separate capital control indices for both inflows and outflows for ten different asset categories. This level of disaggregation of the original data makes possible a more detailed and nuanced analysis of capital controls than with most other capital control indices. For example, these data allow an examination of the co-movements of controls on different types of assets and, for a particular set of asset categories, on the comovements of controls on inflows and outflows. Researchers can also construct more aggregated measures of controls that are well targeted to the specific nature of See Fernández, Klein, Rebucci, Schindler and Uribe (2015). The data set is available on-line at the NBER’s International Finance and Macroeconomics Catalogue of Data Sources, at http://www.nber.org/data/international-finance/ . 4 Two other cross-country data sets that are also based on the AREAER are Quinn (first presented in 1997) and Chinn and Ito (first presented in 2006). Our data set builds on Schindler (2009). 5 the topic being studied; for example, an analysis of interest parity could use an aggregate of controls on fixed-income securities. The ten categories of assets in our data set (and their two-letter abbreviations) are money market instruments (mm, fixed income assets with a maturity of less than one year), bonds (bo, which have a maturity of one year or greater), equities (eq), collective investments (ci), financial credits (fc), real estate (re), commercial credits (cc), derivatives (de), direct investment (di) and guarantees, sureties and financial backup facilities (gs). Figure 1 presents information on the prevalence of controls across asset categories, aggregated across countries and years (the two-letter asset category abbreviations are followed by either i, for controls on inflows, or o, for controls on outflows, with the 21st category, ldi, representing controls on the liquidation of direct investment). This figure shows that the prevalence of controls across countries and across time ranges from 18 percent of observations (for ldi), to 25 percent (for gsi) to 50 percent or greater (for inflow controls on rei, mmo, boo, eqo, cio and deo). The figure also demonstrates that, but for Real Estate and Direct Investment, there is a higher prevalence of controls on outflows than on inflows. To further illustrate a use of our data set, Figure 2 shows the correspondence of countries’ controls on inflows and outflows for indicators that aggregate across categories of assets and years. The left panel presents this information for the 42 High income countries and the right panel for the 58 Medium and Low Income countries. The sizes of the bubbles in these figures reflect the number of countries in a small range. The two panels of this figure show a somewhat higher prevalence of outflow controls than of inflow controls, which is more pronounced for the Medium and Lower Income countries than for the High Income countries. There is a relatively high correlation of inflow and outflow controls on a country-by-country basis (for both sets of countries, the correlation is about 0.8). These figures show just a small range of the rich set of opportunities presented by this data set. Three of us have already used these data to show that the presence of capital controls is relatively stable, and they are imposed in an acyclical manner (Fernández, Rebucci and Uribe 2013). We also show, in our working paper, that these data can be used to distinguish between narrowly targeted, episodic capital controls and longstanding, widely-imposed controls, a distinction that Klein (2012) makes between “gates” and “walls.” The debate over capital controls will likely continue to be one of the central topics related to the discussion of the international monetary system. We hope that our contribution of this data set helps to inform this debate. Figure 1: Proportion of Observations With Controls By Asset Category and Direction of Restriction .55 .5 .45 .4 .35 .3 .25 .2 .15 .1 .05 fc i fc o cc i cc o gs i gs o di i di o ld i m m m i m o bo i bo o eq eq i o ci i ci o de de i o re i re o 0 Asset Category and Direction (Inflow (i) or Outflow (o)) of Restriction Figure 2: Inflow Controls vs. Outflow Controls Countries' Average Values for all Ten Assets, 1995 - 2012 .75 0 .25 .5 Inflow Controls .5 .25 0 Inflow Controls .75 1 58 Medium & Low Income Countries 1 42 High Income Countries 0 .25 .5 .75 Outflow Controls 1 0 .25 .5 .75 Outflow Controls 1 References Bianchi, Javier (2011), “Overborrowing and Systemic Externalities in the Business Cycle”, American Economic Review, 101(7): 3400–26. Benigno, Gianluca, Huigang Chen, Chris Otrok, Alessandro Rebucci and Eric R. Young, (2013), “Financial Crises and Macro-Prudential Policies”, Journal of International Economics, 89(2): 453-470. _________________________________, (2014), “Capital Controls or Exchange Rate Policy? A Pecuniary Externality Perspective,” CEPR Discussion Paper no. 9936. Chinn, Menzie D. and Hiro Ito (2006). “What Matters for Financial Development? Capital Controls, Institutions, and Interactions”, Journal of Development Economics, 81(1): 163-192. Dornbusch, Rudiger (1998), “Capital Controls: An Idea Whose Time is Gone”, mimeo. Fernández, Andrés, Alessandro Rebucci, and Martín Uribe (2014), “Are Capital Controls Countercylical?” mimeo, Columbia University. Fernández, Andrés, Michael W. Klein, Alessandro Rebucci, Martin Schindler and Martín Uribe (2015), “Capital Controls Measures: A New Dataset” NBER Working Paper no. 20,970. Forbes, Kristin (2007), “One Cost of Chilean Capital Controls: Increased Financial Constraints for Smaller Traded Firms,” Journal of International Economics, 71: 294 – 323. Jeanne, Olivier and Anton Korinek (2010), “Excessive Volatility in Capital Flows: A Pigouvian Taxation Approach”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 100(2): 403 – 407. Jeanne, Olivier, Arvind Subramanian, and John Williamson (2012), “International Rules for Capital Controls”, VOX EU, 11 June. Klein, Michael W. (2013), “Capital Controls: Gates versus Walls”, VOX EU, 17 January, 2013. _________________, and Jay Shambaugh (2013), “Is There a Dilemma with the Trilemma?” VOX EU, 27 September. Ostry, Jonathan, Atish Ghosh, Marcos Chamon, and Mahvash S. Qureshi (2011), “Capital Controls: When and Why”, IMF Economic Review, 59(3): 562–580. Quinn, Dennis (1997), “The Correlates of Change in International Financial Regulation”, American Political Science Review, 91(3): 531–51. Rey, Hélène (2013), “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy,” VOX EU, 31 August. Schindler, Martin (2009), “Measuring Financial Integration: A New Data Set”, IMF Staff Papers, 56(1): 222–38.