sim5899-sup-0001_figuresandtables

advertisement

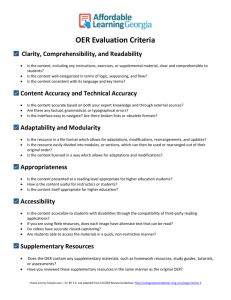

Supplementary material for:

Confidence intervals after multiple imputation:

combining profile likelihood information from

logistic regressions

Georg Heinze1 , Meinhard Ploner2 and Jan Beyea3

1

Section for Clinical Biometrics, Center for Medical Statistics, Informatics and Intelligent Systems, Medical

University of Vienna, Spitalgasse 23, A-1090 Vienna, Austria, georg.heinze@meduniwien.ac.at

2

data-ploner.com, Brunico, Italy

3

Consulting In The Public Interest, 53 Clinton Street, Lambertville, NJ, 08530, USA

1

Contents

1.

2.

3.

4.

Additional results of simulation study, p. 3

CLIP analysis of all parameters in the Alzheimer case-control study, p. 8

MCMC analysis of Alzheimer case-control study, p. 16

Example code for computation of CLIP confidence intervals and CLIP profiles by the R package

logistf, p. 35

2

Additional results of simulation study

Here we summarize some additional results of our simulation study referenced in the main paper.

5-imputations

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 provide the coverage rates of two-sided confidence intervals, if only the

first five imputations are used in the analysis. It can be seen that the five imputations are clearly not

enough for CLIP to reach the nominal level. On the other hand, RR is clearly overcovering. PVR falls in

between these two methods, but still tends to overcoverage. APL’s actual coverage rates are clearly

below the claimed nominal levels.

200-imputations

Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 show the coverage rates of two one-sided nominal 97.5% confidence

intervals with 200 imputations. The results show adequate coverage rates by UPL and CLIP, overcoverage

by RR and partly also by PVR, and undercoverage by APL.

3

Supplementary Table 1: Simulation study: results on coverage of two-sided nominal

95% confidence intervals for 2 , 5 covariates X 2 X 6 with ~30% of the values

missing completely at random (MCAR), 5 imputations, 1000 simulations.

N

j

xj

y

Coverage (two-sided) x 1000 (expected = 950)

UPL

CLIP

RR

APL

PVR

50

0

0.2

0.2

959

930

988

886

973

50

log2

0.2

0.2

953

937

988

898

965

50

log4

0.2

0.2

952

935

978

876

974

50

0

0.5

0.5

955

914

963

859

956

50

log2

0.5

0.5

967

950

985

921

963

50

log4

0.5

0.5

952

946

980

897

967

100

0

0.2

0.2

952

916

977

863

974

100

log2

0.2

0.2

949

912

980

850

972

100

log4

0.2

0.2

932

920

990

853

954

100

0

0.5

0.5

957

913

956

868

950

100

log2

0.5

0.5

951

917

954

864

953

100

log4

0.5

0.5

942

917

961

844

963

UPL, undeleted-data profile penalized likelhood; CLIP, combination of likelihood

profiles; RR, Rubin’s rules; APL, averaging of profile penalized likelihood confidence

limits; PVR, pseudo-variance modification of Rubin’s rules. Coverage is defined as the

proportion of simulated confidence intervals covering the true value.

4

Supplementary Table 2: Simulation study: results on two-sided coverage of nominal

95% confidence intervals for 2 , 5 covariates X 2 X 6 , missingness of X 2

depending on Y and X 3 (MAR), missingness of X 3 X 6 completely at random, 5

imputations, 1000 simulations

N

j

xj

y

Coverage (two-sided) x 1000 (expected = 950)

UPL

CLIP

RR

APL

PVR

50

0

0.2

0.2

967

952

984

916

979

50

log2

0.2

0.2

956

932

988

899

969

50

log4

0.2

0.2

955

937

989

890

977

50

0

0.5

0.5

953

932

983

867

975

50

log2

0.5

0.5

955

917

976

838

961

50

log4

0.5

0.5

950

912

976

833

961

100

0

0.2

0.2

956

940

980

895

970

100

log2

0.2

0.2

954

929

971

880

966

100

log4

0.2

0.2

950

917

970

859

954

100

0

0.5

0.5

948

930

959

869

959

100

log2

0.5

0.5

946

930

976

869

966

100

log4

0.5

0.5

950

923

975

856

967

UPL, undeleted-data profile penalized likelhood; CLIP, combination of likelihood

profiles; RR, Rubin’s rules; APL, averaging of profile penalized likelihood confidence

limits; PVR, pseudo-variance modification of Rubin’s rules. Coverage is defined as the

proportion of simulated confidence intervals covering the true value.

5

Supplementary Table 3: Simulation study: results on coverage of one-sided nominal 97.5% lefttailed/right-tailed confidence intervals for 2 , 5 covariates X 2 X 6 with ~30% of the values

missing completely at random (MCAR), 200 imputations, 1000 simulations.

y Coverage of one-sided left/right-tailed confidence intervals x 1000

N

j

xj

(expected = 975)

UPL

CLIP

RR

APL

PVR

50

0

0.2 0.2

977/982

976/979

995/999

940/959

982/998

50

log2 0.2 0.2

980/973

981/981

999/996

949/958

984/990

50

log4 0.2 0.2

977/975

980/983

990/993

938/957

987/990

50

0

0.5 0.5

981/974

978/976

995/982

937/936

973/982

50

log2 0.5 0.5

975/992

985/993

993/1000

957/982

975/986

50

log4 0.5 0.5

967/985

974/993

983/1000

942/968

987/980

0.2 0.2

973/979

977/973

994/991

936/941

977/998

100 log2 0.2 0.2

964/985

962/980

986/991

905/955

981/991

100 log4 0.2 0.2

966/966

966/984

999/991

912/952

982/983

100 0

0.5 0.5

974/983

974/977

976/984

935/942

976/980

100 log2 0.5 0.5

974/977

964/976

983/981

915/950

974/976

100 log4 0.5 0.5

967/975

975/983

993/985

925/932

984/982

100 0

UPL, undeleted-data profile penalized likelhood; CLIP, combination of likelihood profiles;

RR, Rubin’s rules; APL, averaging of profile penalized likelihood confidence limits; PVR,

pseudo-variance modification of Rubin’s rules. Coverage is defined as the proportion of

simulated confidence intervals covering the true value.

6

Supplementary Table 4: Simulation study: results on coverage of one-sided nominal

97.5% left-tailed/right-tailed confidence intervals for 2 , 5 covariates X 2 X 6 ,

missingness of X 2 depending on Y and X 3 (MAR), missingness of X 3 X 6 completely

at random, 200 imputations, 1000 simulations

y Coverage of one-sided left/right-tailed confidence intervals x 1000

N

j

xj

(expected = 975)

UPL

CLIP

RR

APL

PVR

50

0

0.2 0.2

978/989

981/991

992/1000

954/976

982/997

50

log2 0.2 0.2

978/978

974/986

994/999

945/962

986/993

50

log4 0.2 0.2

981/974

974/985

996/996

953/959

993/987

50

0

0.5 0.5

975/978

980/983

995/994

935/937

985/985

50

log2 0.5 0.5

982/973

970/974

989/986

915/938

984/980

50

log4 0.5 0.5

975/975

968/981

996/988

918/943

989/984

0.2 0.2

974/982

975/988

977/999

947/960

975/997

100 log2 0.2 0.2

973/981

971/986

981/997

936/956

976/992

100 log4 0.2 0.2

979/971

977/978

994/989

940/939

983/983

100 0

0.5 0.5

973/975

977/973

985/984

940/943

981/978

100 log2 0.5 0.5

974/972

972/985

980/987

928/947

975/986

100 log4 0.5 0.5

979/971

977/982

996/983

911/950

989/983

100 0

UPL, undeleted-data profile penalized likelhood; CLIP, combination of likelihood profiles;

RR, Rubin’s rules; APL, averaging of profile penalized likelihood confidence limits; PVR,

pseudo-variance modification of Rubin’s rules. Coverage is defined as the proportion of

simulated confidence intervals covering the true value.

7

CLIP analysis of all variables in the Alzheimer case-control study

This section provides some complementary material on the CLIP analysis of the Alzheimer case-control

study. Supplementary Figures 1-7 contain plots of a CLIP analysis, similarly to Fig. 2 of the main paper,

describing the posterior cumulative distribution function estimated by combining profile likelihoods from

imputed data for the parameters corresponding to age, sex, OCCU, SELF, FAMI, LEIS and the intercept,

respectively. In each of these plots, panel (A) shows the approximated posterior cumulative distribution

functions F ( ) , and the completed-data approximated posteriors F(l ) ( ); l 1,..., 200 ; corresponding

to the 200 imputations. Panel (B) compares deviates from a normal approximation with the mean and

standard error estimated by Rubin’s rules (x-axis) and corresponding deviates from F ( ) . Panel (C)

shows the back-transformed pooled relative profile penalized likelihood functions Dˆ * ( ) / 2 , with

Dˆ * ( ) [ 1 ( F ( ))]2 , which are useful to detect assymmetry in the posterior distribution. Finally, panel

(D) shows the normalized posterior density f ( ) , given by numerical estimation of F ( ) / .

These plots reveal almost perfect coincidence with a Gaussian for the variable age (Supplementary Fig. 1),

and only modest deviation from a Gaussian distribution for the intercept (Supplementary Fig. 7), and for

the parameters corresponding to sex (Supplementary Fig. 2), OCCU (Supplementary Fig. 3) and FAMI

(Supplementary Fig. 4). For these variables, application of Rubin’s rules would be approximately justified.

However, for SELF (Supplementary Fig. 5) the normal approximation is questionable, and for LEIS

(Supplementary Fig. 6) it is clearly unreliable. These plots also reveal that the higher proportion of missing

values in variable LEIS (Supplementary Fig. 6) causes a broader variation of the completed data posteriors

than for the other variables, where no or only few missing values occurred.

8

Supplementary Fig. 1: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the regression parameter corresponding to variable age.

The regression parameter is denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

9

Supplementary Fig. 2: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the regression parameter corresponding to variable sex.

The regression parameter is denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

10

Supplementary Fig. 3: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the regression parameter corresponding to variable OCCU.

The regression parameter is denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

11

Supplementary Fig. 4: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the regression parameter corresponding to variable SELF.

The regression parameter is denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

12

Supplementary Fig. 5: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the regression parameter corresponding to variable FAMI.

The regression parameter is denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

13

Supplementary Fig. 6: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the regression parameter corresponding to variable LEIS.

The regression parameter is denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

14

Supplementary Fig. 7: Alzheimer study: CLIP analysis of the intercept parameter, denoted by .

(A)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior cumulative distribution function obtained by

chi-squared approximation from profile penalized likelihood

(B)

Q-Q plot of normal deviates by Rubin’s Rules approximation and deviates from averaged posterior

cumulative distribution function),

(C)

completed data (gray lines) and pooled (black line) relative profile penalized likelihood

(D)

completed data (gray lines) and averaged (black line) posterior density (derivative of (A)), normalized to a

maximum of 1

15

MCMC analysis of the Alzheimer case-control study

This section describes the MCMC analysis of the case-control study on Alzheimer’s disease.

MCMC analysis was carried out in two steps: first, the Markov chain was run on the first 10 imputed data

sets only, but with a chain length of 100,000. From these, we examined Raftery-Lewis [1] diagnostics and

autocorrelation to decide on 1) the number of burn-in iterations, 2) the number of effective iterations

needed to estimate the 2.5th percentile of the posterior with adequate precision, and 3) the amount of

thinning needed to eliminate autocorrelation. Since the Raftery and Lewis diagnostics typically need a

longer chain to arrive at reliable estimates of the minimum number of iterations required, we evaluated

them only for the first 10 imputed data sets, but with a chain length of 100,000.

Moreover, we monitored the autocorrelation time 1 2 k . The variable

k denotes

autocorrelation of lag k. The sum is over k=1 to k*, where k* is such that all higher-order autocorrelation

terms are lower than 0.05 [2]. The rounded estimated autocorrelation time was used as thinning factor of

the Markov chains, ensuring that no relevant autocorrelation existed in the finally evaluated chains.

The initial run was called using:

proc genmod data=dataalz descending;

ods output autocorr=alz.autocorr_alz ess=alz.ess_alz;

model a1 = age10 a3 a7 a12 a14 a15 / d=bin link=logit;

bayes seed=17 coeffprior=jeffreys nmc=100000 thin=1 nbi=1000 outpost=posterior10alz

diag=(autocorr(lags=1 2 3 4 5) ess);

by X_imputation_;

where X_imputation_<= 10;

run;

Supplementary Tables 5 and 6 summarize the MCMC diagnostics for the first 10 imputed versions of the

Alzheimer data set. Across the six parameters corresponding to risk factors, the maximum number of

burn-iterations was 6 (possibly because with a Jeffreys prior, SAS can start the chain at the analytically

determined posterior mode), and the maximum number of effective iterations was 8,908. Maximum

autocorrelation time was 3.2. These numbers were not apparently different for the intercept parameter.

For analysis of the 200 imputed versions of the Alzheimer data set, we decided to use 100 burn-in

iterations, 9,000 effective iterations and a thinning factor of 3. This yields a total number of

100+3*9,000=27,100 MCMC iterations.

The final run was called using:

proc genmod data=dataalz descending;

ods output autocorr=alz.autocorr200_alz geweke=alz.geweke200_alz

gelman=alz.gelman200_alz heidelberger=alz.heidelberger200_alz

ess=alz.ess200_alz;

model a1 = age10 a3 a7 a12 a14 a15 / d=bin link=logit;

bayes seed=17 coeffprior=jeffreys nmc=27000 thin=3 nbi=100 outpost=posterior10_alz

16

diag=(autocorr(lags=1 2 3 4 5) heidelberger geweke gelman

by X_imputation_;

run;

ess);

Supplementary Table 5: Results of Raftery-Lewis diagnostics as output by SAS/PROC GENMOD over 10

imputed versions of the Alzheimer data set, each with a chain length of 100,000. Variables in the Table

include, nBurn (necessary number of burn-in iterations), median and maximum; nTotal (necessary

number of total iterations), median and maximum.

Parameter N Obs Variable Label

N

Median Maximum

SELF (A12)

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 5.0000000 6.0000000

Total 10

8273.00

8908.00

FAMI (A14)

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 4.0000000 5.0000000

Total 10

7884.50

8593.00

LEIS (A15)

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 3.0000000 6.0000000

Total 10

4351.50

8507.00

Sex (A3)

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 2.0000000 3.0000000

Total 10

3956.50

4095.00

OCCU (A7)

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 2.0000000 3.0000000

Total 10

3953.50

4071.00

Intercept

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 3.0000000 5.0000000

Total 10

4161.00

7878.00

Age (age10)

10 nBurn

nTotal

Burn-in 10 3.0000000 3.0000000

Total 10

4231.50

4472.00

17

Supplementary Table 6: ‘Autocorrelation time’ [2] (median and max), expressed in units of number of

iterations, over 10 imputed versions of the Alzheimer data set as output by SAS/PROC GENMOD.

Analysis Variable : CorrTime Autocorrelation Time

Parameter

N Obs N

Median

Maximum

SELF (A12)

10 10 2.3191092 2.9136267

FAMI (A14)

10 10 1.7964058 2.4611236

LEIS (A15)

10 10 1.6125760 3.1823774

Sex (A3)

10 10 1.7323859 2.7173755

OCCU (A7)

10 10 1.9474537 2.0734939

Intercept

10 10 1.7780654 2.0161502

Age (age10)

10 10 1.6853984 1.9011540

After having determined the burn-ins, the number of iterations and the amount of thinning, we

generated MCMC chains for all 200 imputed data sets. From these we determined the Geweke [3],

Gelman-Rubin [4] and Heidelberger-Welch [5] statistics for assessing convergence of the chains.

Supplementary Figures 8-13 contain the trace plots for the six variables from the first imputed data set.

There is no apparent evidence of any convergence issues.

Heidelberger-Welch diagnostics employ a Cramer-van Mises test to assess if the chain comes from a

covariance stationary process. If the test fails, then the first 10%, say, of the chain could be discarded and

the test repeated with the remaining 90%. This could be repeated until a stationary chain is obtained. As

shown in Supplementary Table 7, the Cramer-von Mises test flagged only few chains as non-stationary.

Trace plots from chains where the stationarity test failed were reviewed (Supplementary Fig. 14 - 18).

There was no apparent evidence for relevant convergence issues, and we attribute these rare

occurrences of non-stationarity to random fluctuations.

Supplementary Table 7: Results from Stationarity Test (Heidelberger-Welch diagnostics)

Variable

Number of imputations

where stationarity test

failed (P<0.05)

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

2 (1%)

3 (1.5%)

0 (0%)

0 (0%)

Intercept

Age

Sex (A3)

OCCU (A7)

SELF (A12)

FAMI (A14)

LEIS (A15)

18

Gelman and Rubin diagnostics are based on multiple chains and compare the variance within chains to

the variance between chains. Essentially, the Gelman-Rubin statistic should be close to 1, indicating

equality of the two variances. To compute Gelman-Rubin diagnostics, at least two additional chains have

to be run, which increases the computing time by a factor of 3. In our implementation, we used different

initial values for each chain.

In SAS, an upper 97.5% confidence bound for the Gelman-Rubin statistic is supplied. We depicted the

distribution of the upper bound over the 200 imputations in histograms, which are shown in

Supplementary Fig. 19-22. In none of the parameters and none of the imputed data sets did the

distribution of the Gelman-Rubin statistic show any relevant deviation from its expected value of 1.

Finally, Geweke z tests were computed, which compare the mean parameter value between the first and

the second half of the chain. Results are shown in Table 8. Under the null hypothesis that there is no

difference, 5% of significant tests would be expected. Overall, in 6.2% of the 1400 chains there was a

significant result.

Summarizing, careful inspection of various MCMC diagnostics offered by SAS/PROC GENMOD in all

imputed data sets confirmed that the chains have reached their stationarity distribution, i.e., they

approximately converged to the posterior distribution to be estimated. Thus, we conclude that the results

obtained from mixing the 200 chains should be reliable.

Supplementary Table 8: Results from Geweke test for equality of mean parameter value between first

and second half of the chain

Variable

Number of imputations

where Geweke test failed

(P<0.05)

Intercept

15 (7.5%)

Age

16 (8%)

Sex (A3)

12 (6%)

OCCU (A7)

14 (7%)

SELF (A12)

9 (4.5%)

FAMI (A14)

8 (4%)

LEIS (A15)

13 (6.5%)

Overall

87 (6.2%)

19

Supplementary Fig. 8: Alzheimer example, trace plot of variable age in imputed data set 1

age10

2

1

0

-1

-2

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

20

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig 9: Alzheimer example, trace plot of variable sex (variable name A3) in imputed data

set 1

A3

4

3

2

1

0

-1

-2

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

21

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 10: Alzheimer example, trace plot of variable OCCU (A7) in imputed data set 1

A7

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

22

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 11: Alzheimer example, trace plot of variable SELF (A12) in imputed data set 1

A12

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

-0.8

-0.9

-1

-1.1

-1.2

-1.3

-1.4

-1.5

-1.6

-1.7

-1.8

-1.9

-2

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

23

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 12: Alzheimer example, trace plot of variable FAMI in imputed data set 1

A14

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

-0.8

-0.9

-1

-1.1

-1.2

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

24

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 13: Alzheimer example, trace plot of variable LEIS in imputed data set 1

A15

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

-0.8

-0.9

-1

-1.1

-1.2

-1.3

-1.4

-1.5

-1.6

-1.7

-1.8

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

25

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 14: Trace plot of variable OCCU (A7) in imputed data set 93.

A7

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

26

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 15: Trace plot of variable OCCU (A7) in imputed data set 126.

A7

1.1

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

27

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 16: Trace plot of variable SELF (A12) in imputed data set 79.

A12

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

-0.8

-0.9

-1

-1.1

-1.2

-1.3

-1.4

-1.5

-1.6

-1.7

-1.8

-1.9

-2

-2.1

-2.2

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

28

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 17: Trace plot of variable SELF (A12) in imputed data set 142.

A12

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

-0.8

-0.9

-1

-1.1

-1.2

-1.3

-1.4

-1.5

-1.6

-1.7

-1.8

-1.9

-2

-2.1

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

29

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 18: Trace plot of variable SELF (A12) in imputed data set 194.

A12

-0.3

-0.4

-0.5

-0.6

-0.7

-0.8

-0.9

-1

-1.1

-1.2

-1.3

-1.4

-1.5

-1.6

-1.7

-1.8

-1.9

-2

-2.1

-2.2

-2.3

-2.4

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

Iteration

30

6000

7000

8000

9000

10000

Supplementary Fig. 19: Alzheimer example, distribution of upper bound of Gelman-Rubin statistic over

the 200 imputations for variables SELF (A12, top) and FAMI (A14, bottom)

31

Supplementary Fig. 20: Alzheimer example, distribution of upper bound of Gelman-Rubin statistic over

the 200 imputations for variables LEIS (A15, top) and sex (A3, bottom)

32

Supplementary Fig. 21: Alzheimer example, distribution of upper bound of Gelman-Rubin statistic over

the 200 imputations for OCCU (A7, top) and the intercept (bottom)

33

Supplementary Fig. 22: Alzheimer example, distribution of upper bound of Gelman-Rubin statistic over

the 200 imputations for age

34

Example R code for CLIP analysis

CLIP analysis is facilitated by a new version of the R package logistf [6]. Here we provide some code examples

illustrating how this package can be used to: (a) obtain CLIP confidence intervals after multiple imputation, (b)

obtain confidence intervals based on the pseudo-variance modification of Rubin’s rules, (c) display the profile of

the combined posterior to determine whether the assumptions of Rubin’s rules are adequate. We start by using

some R code to generate the data for the toy example of Section 2.5 of the main paper:

R>

R>

R>

+

R>

+

R>

#generate data set with NAs

freq=c(5,2,2,7,5,4)

y<-c(rep(1,freq[1]+freq[2]), rep(0,freq[3]+freq[4]), rep(1,freq[5]),

rep(0,freq[6]))

x<-c(rep(1,freq[1]), rep(0,freq[2]), rep(1,freq[3]), rep(0,freq[4]),

rep(NA,freq[5]), rep(NA,freq[6]))

toy<-data.frame(x=x,y=y)

The toy data set now looks as follows:

R> toy

x y

1

1 1

2

1 1

3

1 1

4

1 1

5

1 1

6

0 1

7

0 1

8

1 0

9

1 0

10 0 0

11 0 0

12 0 0

13 0 0

14 0 0

15 0 0

16 0 0

17 NA 1

18 NA 1

19 NA 1

20 NA 1

21 NA 1

22 NA 0

23 NA 0

24 NA 0

25 NA 0

Next, five imputed versions of the data set are generated:

R> set.seed(169)

R> toymi<-list(0)

R> for(i in 1:5){

+

toymi[[i]]<-toy

+

y1<-toymi[[i]]$y==1 & is.na(toymi[[i]]$x)

+

y0<-toymi[[i]]$y==0 & is.na(toymi[[i]]$x)

+

xnew1<-rbinom(sum(y1),1,freq[1]/(freq[1]+freq[2]))

+

xnew0<-rbinom(sum(y0),1,freq[3]/(freq[3]+freq[4]))

+

toymi[[i]]$x[y1==TRUE]<-xnew1

35

+

+

toymi[[i]]$x[y0==TRUE]<-xnew0

}

The imputed versions have their NA’s in x replaced by 0’s and 1’s, following the conditional distribution of the

observed x, conditional on y. Here we print the first imputed data set:

R > toymi[[1]]

x y

1 1 1

2 1 1

3 1 1

4 1 1

5 1 1

6 0 1

7 0 1

8 1 0

9 1 0

10 0 0

11 0 0

12 0 0

13 0 0

14 0 0

15 0 0

16 0 0

17 1 1

18 0 1

19 0 1

20 0 1

21 0 1

22 0 0

23 1 0

24 0 0

25 0 0

In the following code, each imputed data set is analysed using logistf to produce a list of logistf model fits:

R> fit.list<-lapply(1:5, function(X) logistf(data=toymi[[X]], y~x, pl=TRUE))

For illustration, we summarize the results of the first completed-data analysis:

R> fit.list[[1]]

logistf(formula = y ~ x, data = toymi[[X]], pl = TRUE)

Model fitted by Penalized ML

Confidence intervals and p-values by Profile Likelihood

coef se(coef) lower 0.95 upper 0.95

Chisq

p

(Intercept) -0.4795731 0.5144434 -1.5161357 0.4801805 0.9500591 0.3297042

x

1.0986124 0.8677860 -0.4873944 2.8248767 1.8270245 0.1764794

Likelihood ratio test=1.827024 on 1 df, p=0.1764794, n=25

CLIP confidence limits

CLIP confidence intervals for the intercept coefficient and the regression coefficient of variable x can simply be

computed using a one-line command:

R> CLIP.confint(fit.list)

36

CLIP.confint(obj = fit.list)

Number of imputations: 5

Iterations, mean:

12.75

max: 17

Confidence level, lower: 2.5 %, upper: 97.5 %

Estimate

Lower

Upper

P-value

(Intercept) -0.9316852 -2.51968459 0.2696288 0.14081509

x

1.7767921 -0.07298734 3.9234581 0.06041205

The output of the function first gives some general information on the number of imputations found in the input

object, and the mean and maximum number of imputations needed to compute the four confidence limits (lower

and upper for intercept and x). Then, it provides a table with the pooled regression coefficients (labelled

‘Estimate’), and the lower and upper confidence limits based on the pooled posterior. The P-value directly follows

from inverting the confidence interval.

Pseudo variance modification of Rubin’s rules

Using the R command PVR.confint, confidence intervals based on the pseudo-variance modification of Rubin’s rules

can be obtained. The output not only contains the computed limits, but also the lower and upper pseudo variance,

which allows a quick check on their agreement. E.g, for variable x the upper pseudo-variance is only about 18.5%

higher than the lower one, which means that the assumptions for Rubin’s rules are roughly fulfilled.

R> PVR.confint(fit.list)

Pseudo-variance modification of Rubins Rules

Confidence level: 95 %

Estimate

Lower

Upper Lower pseudo variance Upper pseudo variance

(Intercept) -0.9316852 -2.489119 0.4337575

0.6314269

0.4853453

x

1.7767921 -0.244709 3.9780441

1.0637799

1.2613724

Profile of the posterior

The profile of the posterior for the regression parameter x, using the CLIP method, can be obtained by the R

command:

R> xprof<-CLIP.profile(fit.int, variable="x", keep=TRUE)

The keep=TRUE directive requests the program to keep all five completed-data profiles in the output object. A

convenient plot method allows to plot the profile:

R> plot(xprof)

While this will display the profile as log likelihood ratio (relative to the maximum), one may alternatively plot the

profile as the cumulative distribution function or as a density:

R> plot(xprof, “cdf“)

R> plot(xprof, “density“)

The results of the three plot commands are shown in Supplementary Figures 23-25.

37

-2

-3

-4

-5

-6

Relative log profile penalized likelihood

-1

0

Supplementary Fig. 23: CLIP estimate of the pooled posterior (solid black line), and completed-data profile

likelihoods (dashed gray lines) for parameter x in the toy example. The scaling of the profiles is in terms of the

likelihood ratio statistic (twice the difference to the maximized log likelihood).

0

1

2

38

3

4

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

Cumulative distribution function

0.8

1.0

Supplementary Fig. 24: CLIP estimate of the cumulative distribution function of the pooled posterior (solid black

line), and completed-data cumulative distribution functions (dashed gray lines) for parameter x in the toy example.

0

1

2

39

3

4

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

Posterior density

0.8

1.0

Supplementary Fig. 25: CLIP estimate of the density of the pooled posterior (solid black line), and completed-data

densities (dashed gray lines) for parameter x in the toy example.

-2

0

2

40

4

6

While these graphs may already provide some guidance for checking the adequacy of Rubin’s rules in this example,

many researchers are familiar with checking the normal distribution by means of Q-Q plots. By computing the

pooled variance following Rubin’s rules with the pool.RR function of logistf, one may generate such a plot with a

few simple commands. A pooled analysis by Rubin’s rules of the five completed-data analyses is obtained by

R> RR.sum<-summary(pool.RR(fit.list))

R> RR.sum

est

se

t

df Pr(>|t|)

lo 95

hi 95 nmis

fmi

lambda

(Intercept) -0.9316852 0.7466744 -1.247780 42.31076 0.2189735 -2.438207 0.5748368

NA 0.3074713 0.3074713

x

1.7767921 1.0930820 1.625488 39.22362 0.1120679 -0.433772 3.9873562

NA 0.3193421 0.3193421

We extract mean and standard error for the regression coefficient of x from this table, and use them to generate

normal deviates according to the CDF values that are already contained in the profile object created above. The

normal deviates can then be plotted against the CLIP deviates to see if there is a relevant disagreement.

R>

R>

R>

R>

+

+

R>

m<-RR.sum[2,1]

s<-RR.sum[2,2]

normq<-qnorm(prof$cdf)*s+m

plot(normq, prof$beta, xlab="Normal deviate", ylab="Pooled posterior deviate",

xlim=quantile(c(normq, prof$beta),c(0,1)),

ylim=quantile(c(normq,prof$beta),c(0,1)))

lines(normq,normq,lty=1,col="gray")

Although the disagreement between the normal deviates and the CLIP deviates is not too large, the lower limit is

considerably closer to 0 by the CLIP method than by the normal approximation. Since the lower limit is in the area

where the Q-Q plot shows the largest disagreement, it may be safer to prefer the CLIP method in this illustrative

example. However, it should be emphasized again that generally a higher number of imputations is recommended

(at least 100), in particular with data sets as small as this one.

41

2

1

0

-1

Pooled posterior deviate

3

4

Supplementary Fig. 26: Q-Q plot of normal deviates based on Rubin’s rules and deviates from the CLIP estimate of

the CDF of the posterior

-1

0

1

2

Normal deviate

42

3

4

References

[1] Raftery, A. E. and Lewis, S. M. (1992), “One Long Run with Diagnostics: Implementation

Strategies for Markov Chain Monte Carlo,” Statistical Science, 7, 493–497.

[2] Kass, R. E., Carlin, B. P., Gelman, A., and Neal, R. (1998), “Markov Chain Monte Carlo in

Practice: A Roundtable Discussion,” The American Statistician, 52, 93–100.

[3] Geweke, J. (1992), “Evaluating the Accuracy of Sampling-Based Approaches to Calculating

Posterior Moments,” in J. M. Bernardo, J. O. Berger, A. P. Dawiv, and A. F. M. Smith, eds., Bayesian

Statistics, volume 4, Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

[4] Gelman, A. and Rubin, D. B. (1992), “Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple

Sequences,” Statistical Science, 7, 457–472.

[5] Heidelberger, P. and Welch, P. D. (1981), “A Spectral Method for Confidence Interval

Generation and Run Length Control in Simulations,” Communication of the ACM, 24, 233–245.

[6] Heinze G, Ploner M, Dunkler D, Southworth H,. logistf: Firth’s bias reduced logistic regression. R

package version 1.20. available at: http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/logistf/index.html (16

May 2013).

43