Stability of Human telomeric G-Quadruplex DNA with Actinomycin-D

advertisement

Stability of Human telomeric G-Quadruplex DNA with

Actinomycin-D

Rushi Ghizal

Physics Department

Integral University,Kursi Road,

Lucknow, 226066.U.P,India.

rushi_ghizal@yahoo.co.in

Gazala Roohi Fatima

Seema Srivastava

Physics Department

Integral University,Kursi Road,

Lucknow, 226066.U.P,India.

gazala03@gmail.com

Physics Department

Integral University, Kursi Road,

Lucknow, 226066. U.P,India.

seemasr1@rediffmail.com

ABSTRACT

The theory of cooperative transitions has

been applied to explain the stability and melting

behavior of Telomeric G-Quadruplex DNA. The

transition profiles and heat capacity curves are

best explained in terms of two variable

parameters, namely nucleation and propagation

parameters. Greater stability is achieved in

presence of K+ ions, compared with Na+ ion. It is

ascribed to dipole and dipole-induced

transitions.

Keywords

G-Quadruplex, transition profiles, heat capacity.

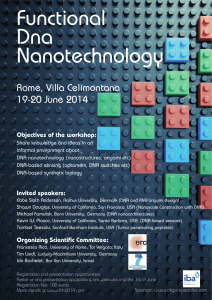

Fig 1. Chemical structure of Actinomycin D

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years the study of small molecules

that selectively target and stabilize the Gquadruplex structures have emerged as an area

of tropical interest. This DNA structure motif

(G-quadruplex) has emerged as a novel and

exciting target for the discovery and design of

new class of anticancer drugs [1-3].

Recently Jason S.H, et al. [4] have reported

thermodynamic and structural characterization

of human telomeric G-quadruplex.In their work

an interaction between actinomycin D (Fig. 1)

and

human

telomeric

sequence

d[AGGG(TTAGGG)3] have been presented.

The thermal melting profiles were obtained for

both free and bound Na+ and K+ forms of the Gquadruplex DNA structure using differential

scanning calorimetry. Their study shows that in

presence of K+ ions, guanine forms a more

stable tetramolecular complex, compared with

Na+ ions.

In the present study, we have used the theory

of co-operativity for a finite system to generate

the transition profiles and λ-point anomaly in

heat capacity at transition point. The heat

capacity measurements of Jason S.H, et al. [4],

have provided the input information. The

alteration in nucleation parameter, which is

inverse measure of binding strength, reflects the

effect of actinomycin D binding.

2. THEORY

The stability of G-Quadruplex is directly

related to the strength and number of hydrogen

bonds. They are also responsible for cooperativity enhancement. Thus, the melting of

such molecules, which involve both positional

and orientational disordering, can be treated as

two-phase problem. Thus we can modify Zimm

and Bragg theory [5]. In brief, the above theory

consist of writing an Ising matrix for two phase

system, the bonded state and unbounded state.

As discussed earlier [5-10], the Ising matrix 𝑀

can be written as-

1

𝑓𝑟2

𝑓𝑟

1

2

𝑓𝑘

1

2

𝑓𝑟

𝑓𝑟 𝑓𝑟

𝑀 = 𝑓𝑘

𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2

1

1

2

1

2

𝑓ℎ [𝑓 𝑓

ℎ 𝑟

1

2

0

𝑓𝑘2 𝑓ℎ2

0

1

2

2

[ 𝑓ℎ ]

1

(1)

1

2

𝑓ℎ 𝑓ℎ ]

Where, 𝑓𝑟 , 𝑓ℎ and 𝑓𝑘 are corresponding base

pair partition function contributions in the three

states (i.e ordered, disordered and boundary or

nucleation). G-G and T-T have been assumed to

have the same statistical weight because

according to crystallographic studies reported

recently [6], both thymine and guanine are

hydrogen-bonded in a tetrad complex in the

same manner. The hydrogen bond lengths are

approximately the same. The eigen values for M

are given by:

1

1

(3)

𝑓𝑘2

1

0

1

1

𝑉=

𝑓𝑟 𝑓𝑘

1

1

2

𝑓ℎ

The partition function for a 𝑁 -segment chain is

given by:

𝑍 = 𝑈 𝑀𝑁−1 𝑉

(4)

The matrix 𝑇 which diagonalizes M consists of

the column vectors given by:

𝑀𝑋 = 𝜆𝑋

(5)

Where

𝑋1

𝑋 = [ 𝑋2 ]

𝑋3

By substituting the value of 𝑀 from Eq. 1 in Eq.

5, we get

𝜆1 = 2 [(𝑓𝑟 + 𝑓ℎ ) + {(𝑓𝑟 − 𝑓ℎ )2 + 4𝑓𝑟 𝑓𝑘 }2 ]

1

1

𝜆2 = [(𝑓𝑟 + 𝑓ℎ ) − {(𝑓𝑟 − 𝑓ℎ )2 + 4𝑓𝑟 𝑓𝑘 }2 ]

2

𝜆3 = 0

1

1

(𝜆1 −𝑓𝑟 )

(𝜆2 −𝑓𝑟 )

1 1

Since we are dealing with finite system, hence

the effect of initial and final states becomes

important. The contribution of the first segment

to the partition function is given by a row vector

𝑈. It is assumed that the initial state is

disordered state.

1

2

𝑈 = [(𝑓𝑟 , 0, 0)]

(2)

Similarly, the column 𝑉 gives the state of last

segment,

1 1

(𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2 )

(𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2 )

1 1

(𝑓ℎ2 𝑓𝑟2 )

1 1

(𝑓ℎ2 𝑓𝑟2 )

[(𝜆1 −𝑓ℎ )

(𝜆2 −𝑓ℎ )

𝑇=

1

1

1

−𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2

(6)

1

1

−𝑓ℎ2 𝑓𝑟2 ]

Similarly, we get 𝑇 −1 from the matrix equation:

𝑌𝑀 = 𝜆𝑌

(7)

Where

𝑌 = [𝑌1

𝑌2

𝑌3 ]

Again, by substituting the values of 𝑀 from Eq.

1 in Eq. 7, we get:

𝐶1

𝐶1

𝑇 −1 = 𝐶

2

𝐶2

1 1

1 1

𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2

𝑓𝑘 𝑓𝑟2 𝑓ℎ2

𝐶1 𝜆

1 (𝜆1 −𝑓ℎ )

1 1

𝑓𝑘 𝑓𝑟2 𝑓ℎ2

𝜆1

1 1

𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2

2 (𝜆2 −𝑓ℎ )

1 1

𝑓𝑘 𝑓𝑟2 𝑓ℎ2

1 1

[𝐶3

𝐶3

(8)

𝐶2 𝜆

𝜆2

𝑓𝑟2 𝑓𝑘2

𝐶3 𝜆

]

3 (𝜆3 −𝑓ℎ )

𝜆3

The normalizing constants are:

𝐶1 =

(𝜆1 −𝑓ℎ )

(𝜆1 −𝜆2 )

, 𝐶2 =

(𝜆2 −𝑓ℎ )

(𝜆2 −𝜆1

, 𝐶3 = 0

)

(9)

If we let 𝛬 = 𝑇 −1 𝑀𝑇 be he diagonalized form

of 𝑀, the partition function can be written as:

𝑍 = 𝑈𝑇𝛬𝑁−1 𝑇 −1

(10)

The extension of this formalism is straight

forward. The specific heat is related to molar

enthalpy and entropy changes in the transition

from state I to state II. From well-known

thermodynamic relations, free energy and

internal energy are 𝐹 = −𝐾𝑇𝑙𝑛𝑍 and 𝑈 =

−𝑇 2 (𝛿/𝛿𝑇)(𝐹/𝑇) respectively. Differentiating

internal energy with respect to temperature we

get the specific heat:

𝐶𝑣 =

1

𝛿𝑙𝑛𝑍

𝑁

𝛿𝑙𝑛𝑓𝑟

𝑚

(11)

]

𝑄𝑟 = 2 +

(1−𝑆)(2𝐴−1)

2𝑃

+

(1+𝑆){(2𝐴−1)𝑃 −1 +𝑠}

2𝑃 2 𝑁

)

(14)

1

− ( 3 ) [{(2𝐴 − 1)𝑃 − 1

2𝑃 𝑁

+ 𝑠}2(𝑠 + 1)]

(12)

Where

𝑃=

𝛿𝑠

+ {(2𝐴 − 1)𝑃 − 1 + 𝑠}}]

Solving the above equation, we get

1

2 𝑠𝛿𝑄

𝑟

𝛿𝑄𝑟

1

𝛿𝐴

= ( 2 ) [2𝑃(1 − 𝑠)

− 𝑃(2𝐴 − 1)

𝛿𝑠

2𝑃

𝛿𝑠

𝛿𝑃

− (1 − 𝑠)(2𝐴 − 1)

]

𝛿𝑠

1

+ ( 3 ) [𝑃 {(𝑠

2𝑃 𝑁

𝛿𝑃

𝛿𝐴

+ 1) {(2𝐴 − 1)

+ 2𝑃

+ 1}

𝛿𝑠

𝛿𝑠

The fraction of the segments in the disordered

form is given by

𝑄𝑟 = [ ] [

𝛿𝑇

∆𝐻

= 𝑁𝑘 (𝑅𝑇 ) (

Where ∆𝐻 is the molar change in enthalpy

about the transition point, 𝑇𝑚 is the transition

temperature, and

On substituting the values from Eqs. 1, 2, 3, 6, 8

and 9 in Eq. 10, the partition function becomes:

𝑍 = 𝐶1 𝜆1𝑁 + 𝐶2 𝜆𝑁

2

𝛿𝑈

With

(𝜆1 −𝜆2 )

𝑓𝑟

,𝑠=

𝑓ℎ

𝑓𝑟

𝑓𝑘

, 𝜎=

−

𝐴 = [(𝑓𝑟 − 𝑓ℎ )2 + 4𝑓𝑘 𝑓𝑟 ]

𝑓𝑟

,

𝛿𝐴

𝛿𝑠

1

2

Here 𝑠 is propagation parameter, which for

simplicity is assumed to be 1. In fact, in most of

the systems, it is found to be close to unity. If

𝐴𝑟 and 𝐴ℎ are the absorbance in disordered and

ordered states, respectively, the total absorption

can be written as:

𝐴 = 𝑄𝑟 𝐴𝑟 + (1 − 𝑄𝑟 )𝐴ℎ

(13)

𝛿𝑃

𝛿𝑠

= {

=

(𝑠−𝜎)𝑁

𝑍 2

𝑓𝑁

𝑟

(𝑠−1)

𝑃

𝜎

} × (𝑃3 ) × [−2 + 𝑁

, 𝜎=

(𝑠−2𝜎−1)

(𝑠−𝜎)

]

𝑓𝑘

𝑓𝑟

Where 𝜎 is nucleation parameter and is a

measure of the energy expanded/released in the

formation (uncoiling) of first turn of the

ordered/disordered state. It is related to the

uninterrupted sequence lengths [5]. The volume

heat capacity 𝐶𝑣 has been converted into

constant pressure heat capacity 𝐶𝑝 by using the

Nernest-Lindermann approximation [11-12].

𝐶𝑝2 𝑇

𝐶𝑝 − 𝐶𝑣 = 3𝑅𝐴0 (𝐶

𝑣 𝑇𝑚

)

(15)

Where 𝐴0 is a constant often of a universal

value [3.9 x 10-3 (K mol/J)] and 𝑇𝑚 is the

melting temperature.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Transition Profiles

When Actinomycin D binds to GQuadruplex DNA, the structure of DNA still

remains highly co-operative and hence two state

theory of order/disorder transitions is applicable.

The Zimm-Bragg theory is amended so as to

consider ordered and disordered states

(bounded/unbounded), as the two states coexist

at the transition point. The transition is

characterized mainly by the nucleation

parameter

and

overall

change

of

entropy/enthalpy, which are also the main

thermodynamic force driving the transitions.

The change in enthalpy obtained from

differential scanning calorimetric (DSC)

measurements takes all this into account. This is

evident from the enthalpy changes and the

changes in other transition parameter, such as

nucleation parameter (𝜎) and melting point

(Table 1 and Table 2). The result obtained from

the theoretical study suggested that the binding

of Actinomycin D increases the melting

temperature of G-Quadruplex DNA (for both K+

and Na+ forms). At saturation the melting point

of K+ G-Quadruplex DNA was increased with

9.375 K in comparison with free G-Quadruplex.

Similarly, the melting point of Na+ GQuadruplex was increased with 18.25 K The

sharpness of the transition can be looked at in

terms of half width and sensitivity parameter

defined as (∆𝐻/𝜎). The deviations in half-width

and sensitive parameters scientifically revealed

that the transition is sharp in case of unbounded

state and goes blunt with Actinomycin D

saturation. In case of 𝜆-transition, the same

trend in the sharpness of transition is seen

between the Actinomycin D boned as well as

unbounded curves. As, anticipated, the

sharpness is better in unbound state as compared

to bound state. A range of parameters, which

give transition profiles in best agreement with

the experimental measurements for binding of

Actinomycin D to G-Quadruplex DNA (K+ and

Na+ forms) are given in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1. Transition Parameters for Actinomycin D binding

to G-Quadruplex (K+ form).

Parameters

Unbonded

GQuadruplex

DNA

341.75

𝑇𝑚 (K)

4

1.6X10

∆𝐻(Kcal/Mbp)

0.0046

𝜎

56

𝑁

Half Width

12

(Exp)

Half Width

12

(Theo)

Sensitivity

3.478X106

parameter

(∆𝐻/𝜎)

G-Quadruplex

DNA bonded

with

Actinomycin D

351.125

1.1X104

0.00061

56

7.5

7.5

1.083X107

Table 2. Transition Parameters for Actinomycin D binding

to G-Quadruplex (Na+ form).

Parameters

𝑇𝑚 (K)

∆𝐻(Kcal/Mbp)

𝜎

𝑁

Half Width

(Exp)

Half Width

(Theo)

Sensitivity

parameter

(∆𝐻/𝜎)

Unbonded

GQuadruplex

DNA

333

2.4X104

0.015

56

8

G-Quadruplex

DNA bonded

with

Actinomycin

D

351.25

1.5X104

0.00099

56

7.5

8

7.5

1.6X106

1.515X107

Experimental Cp

1

Absorbance

Specific Heat (Kcal/mol K)

1

0.75

Theoretical Cp

Predicted Value

0.5

0

290

0.5

320

350

Temperature (K)

0.25

0

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

360

Temperature (K)

Fig. 2 Heat Capacity and transition profile of free K+

form of the G-quadruplex DNA structure.

370

Experimental Cp

Theoretical Cp

1

1

Predicted Value

Absorbance

Specific Heat ( (Kcal/mol K)

3.2. Heat Capacity

Heat capacity, second derivative of the free

energy, has been calculated by using Eq. 14 and

15, which is used to characterize conformational

and dynamical states of a macromolecular

system. These heat capacities with 𝜆-point

anomaly along with their transition profiles for

unbounded G-Quadruplex DNA (K+ form) is

shown in Fig. 2 and for Actinomycin D bonded

to G-Quadruplex DNA (K+ form) is shown in

Fig. 3. The results revealed that the theoretically

obtained heat capacity profiles agreed with the

experimentally reported one and could be

brought almost into concurrence with the use of

scaling factors. Minor insignificant deviations at

the tail end is primarily due to the presence of

various disordered states and presence of short

helical segments found in random coil states.

The predicted values of absorbance for both

unbounded and bonded state are also given in

Fig. 2 and Fig. 3.

0.75

0.5

0

0.5

290

320

350

Temperature (K)

0.25

0

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

360

370

Temperature (K)

Fig. 3 Heat Capacity and transition profile of K + form of the

G-quadruplex DNA structure bonded with Actinomycin D

Similarly the heat capacities and their

transition profiles for unbounded G-Quadruplex

DNA (Na+ form) is shown in Fig. 4 and for the

Actinomycin D bonded to G-Quadruplex DNA

(Na+ form) is shown in Fig.5. Again one

observes that the theoretically obtained heat

capacity profiles agreed with the experimentally

reported ones. The sharpness of the transition

can be characterized by half width of the heat

capacity curves that are in good agreement in

both experimental and theoretical graphs. Again

the predicted absorbance is shown in Fig. 4 and

Fig. 5 for unbounded and bonded states. It must

also be noted that the heat capacities and the

transition profiles of G-Quadruplex (K+ form

and Na+ form) revealed that greater stabilization

is achieved in presence of K+ ions, compared to

Na+ ions.

Experimental Cp

Absorbance

Specific Heat (Kcal/mol K)

Predicted Value

1

1

Theoretical Cp

0.5

0

0.75

290

320

350

Temperature(K)

0.5

0.25

0

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

360

370

Temperature (K)

Fig. 4 Heat Capacity and transition profile of free Na+ form

of the G-quadruplex DNA structure.

Experimental Cp

Theoretical Cp

REFERENCES

1

Predicted Value

Specific Heat (Kcal/mol K)

Absorbance

1

0.5

0.75

0

290

0.5

320

350

Temperature (K)

0.25

0

290

300

310

320

330

340

350

360

370

Temperature (K)

Fig. 5 Heat Capacity and transition profile of Na+ form of

the G-quadruplex DNA structure bonded with Actinomycin

D

4. CONCLUSION

The present study concluded that the DNA

molecule is an extremely co-operative structure

and when Actinomycin D binds to it, the cooperativity is not so much disturbed. Therefore

the amended Zimm Bragg theory (phase

transitions theory) can be effectively applied to

it. It generates the experimental transition

profiles and 𝜆-point heat capacity anomaly

successfully. These results will allow us to

assess the thermodynamic profile of binding

process. Our theoretical data also demonstrates

that the binding of Actinomycin D to GQuadruplex DNA is an endothermic process and

that the binding increases the melting

temperature of the quadruplex. Therefore the

theoretical analysis presented in this study can

be implicated to understand bimolecular

interactions and may also be applied in

biomedical industries for drug design and

development.

1. Han, H., and Hurley, L. H. 2000. Gquadruplex DNA: a potential target for

anti-cancer

drug

design.

Trends

Pharmacol Sci 21, 136-142.

2. Hurley, L. H. 2001. Secondary DNA

structures as molecular targets for cancer

therapeutics. Biochem Soc T 29, 692696.

3. Sun, D., Thompson, B., Cathers, B. E.,

Salazar, M., Kerwin, S. M., Trent, J. O.,

Jenkins, T. C., Neidle, S., and Hurley, L.

H. 1997. Inhibition of human telomerase

by

a

G-quadruplex-interactive

compound. J Med Chem 40, 2113-2116.

4. Jason, S. H., Sonja, C. B., and David, E.

G. 2009. Interactions of Actinomycin D

with Human Telomeric G- Quadruplex

DNA. Biochemistry-US, 48(21), 44404447.

5. Zimm, B. H., and Bragg, J. K. 1959.

Theory of phase transition between helix

and random coil in polypeptide chains. J

Chem Phys. 31, 532-535.

6. Srivastava, S., Gupta, V. D., Tandon, P.,

Singh, S., and Katti, S. B. 1999. Drug

binding and order–order and orderdisorder transitions in DNA triple

helixes. J Macromol Sci Phys. 38, 349366.

7. Srivastava, S., Srivastava, S., Singh, S.,

and Gupta, V. D. 2001. Stability and

transitions in a DNA tetraplex: a model

of telomers. J. Macromol. Sci. Phy.

40(1), 1-14.

8. Srivastava, S., Khan, I. A., Srivastava,

S., and Gupta, V. D. 2004. A theoretical

study of stability of DNA binding with

cis/trans platin. Indian J. Biochem.

Biophys. 41, 305-310.

9. Polkar, N., Pilch, D. S., Lippard, S. J.,

Redding, E. A., Dunham, S. U., and

Breslauer, K. J. 1996. Influence of

cisplatin intrastrand crosslinking on

conformatiom, thermal stability and

energetic of a 20-mer DNA duplex.

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA. 93, 76067611.

10. Roles, K. A., and Wunderlich, B. 1991.

Heat capacities of solid poly(amino

acids). I. polyglycine, poly(L-alanine)

and poly(L-valine). Biopolymers. 31,

477-487.

11. Pan, R., Verma, M. N., and Wunderlich,

B. 1989. J. Therm. Ann. 35, 955-961.

12. Roles, K. A., Xenopoulos, A., and

Wunderlich, B. 1993. Biopolymers. 33,

753-755.