Read an extract from - Writers` Centre Norwich

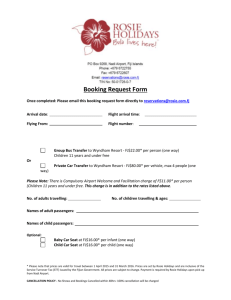

advertisement

Ring Master, K.J. Packer Now. Is this my first memory? Or will you come to say that it is not really mine, that it is merely the story of it – told to me, told in front of me, told within my earshot; told so many countless times until such day that I am old enough to tell it myself? Told me by Uncle Walter as he bumps me on his knee, for interminable years ‘til he will reckon me good and ready to be taught the ways of his world. Told all around me at after-show swills, end-ofseason banquets, christenings, weddings and funerals, all the many and varied – but much the same really – social gatherings that are the very glue forever binding the Boothe’s and Broome’s; or so the families think and hope and wish. Told in low whispers by scores of children no bigger than myself, troubled by their agonising between wanting my friendship and encouraging my fear of them. I am womb-bound, and high above the ground – thirty feet maybe – looking down along the ruffled length of a red-stockinged leg, beyond a slippered-foot, onto snow – a crisp white carpet, frigid and unbending – though truly I could not yet know what snow is, or what colour is white. Or was it a shimmering blue-tinged sea of ice? Or an arctic waste patrolled by ravenous polar bears? It is late November and the air is as sharp as any living soul can remember, so cold that your breath turns to frost on your gin glass and your fingertips stick to it; so cold that when Nell sneezes, the nasal shower turns to ice as it leaves her trunk. I am hidden beneath the leaden folds of Mother’s huge black walking dress, which is big enough and comical enough to conceal the bulk of a full termer. Nobody knows of my existence, except perhaps Mary, Mother’s sister, though she will afterwards always claim otherwise. But then, so the story is told, she seems no less flabbergasted than are all of the onlookers, including Walter, when my first memory happens, so I reckon she might be telling the truth after all. Mother, it seems, has told no living soul, and would rather take her secret to the grave. There is much noise – laughter, shouting, gasping and screaming – then mostly just gasping and screaming. Gasping, as Mother – Madame Rouge, the lady rope-walker – finds that her left foot has shifted in its loose binding. She glances down, in a leisurely sort of panic, and grips harder on her balancing pole, one end of which tips into my view for a moment. She knows that something is not quite right. ‘I checked it and double-checked it, did I not?’ she quizzes herself. But has she simply forgotten? Is it yesterday and not today that she is remembering, in the mechanical way bred from routine? Gasping, as she loses her focus and balance for a tottering moment, before she recovers herself and breathes a cautious sigh of relief – a salutary acknowledgement of a danger passing, a mental note and lesson learnt. My view alters: I see a churchyard now, a derelict stone tower strangled with ivy and dusted with new snow. I see untended graves and ominous-looking giant plants that might be prehistoric. Gasping, as Rosie shifts her weight once more, succumbing to the extra load with which I have so burdened her. Screaming, as Rosie is seen to lose her balance. There are many ways to fall: she might slip with her legs one each side of the rope, but she would fear the rope slicing into my tender skull – for I am truly a head-first baby; she might topple from the rope and spin through the air like a seedling on the wind. But Rosie simply drops her pole, slides to one side and plummets, much like that stone tower would. We fall those thirty feet – the cold air teasing the whiskers of © K.J. Packer 2011 Ring Master, K.J. Packer my new skin – to where we spill our common blood and paint the ice-solid ground an oily red. This moment, this very beginning and end, will be painted so many scores of times that to attempt separating memory from story – the hearsay, the gossip, the artistic licence, the embellishment – will be quite pointless. I will observe this scene as many times as I will be told of it – painted on sheets of scrim as tall as houses, bedecking wooden hoardings as wide as a whole street of houses, and as frescoes grand enough to adorn the Queen’s own castle walls. Those were deft and dangerous actions that were taken to deliver me safe from Mother’s dead womb – of that there can be no doubt. And yet I was presented with such apparent aplomb to the restive public. It is said that my hair turned from gypsy black to silvery-white in just the time it took for my umbilical cord to be cut. Then the tiny scrap of flesh that was me was grabbed by the slippery ankles, heaved high above the heads of the crowd, and given a good old slap on the arse. After which I was pulled to the nearest breast to feel the first wet warmth of life. © K.J. Packer 2011