MSW LEACHATE TREATMENT BY ELECTROCHEMICAL OXIDATION

advertisement

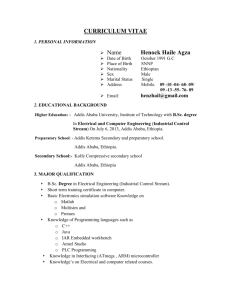

SLUM UPGRADING IN ETHIOPIA: URBAN WAYS FOR SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Author: Academic degree: University: Thesis defence date: e-mail: Valentina Fiore Linares, Ms in Architecture University of Florence 29/04/2011 valentinalinares@hotmail.it Keywords: Slum Upgrading, Sustainable Development, Community Participation Abstract: After a deep and complex analysis of the city of Addis Ababa, which ranges from the historical heritage to the latest measures applied in urban development, I choose as case study for this thesis an urban area characterized by the coexistence of formal and informal settlements. Then, through the comparative analysis of the area's needs and potential, I proposed a scenario based on hierarchies of urban public spaces, permeability of the residential zones and integration between residential, commercial and traditional handcrafts activities (processing of bamboo, wood and iron, textiles and agricultural production). The aim is to establish guidelines for the upgrading of informal settlements, respecting the traditional way of living the space and the social networks. 1. INTRODUCTION Ethiopia is the second most populated country in the Sub-Saharan Africa, with 85 million of inhabitants. At the same time is one of the least urbanized countries, with only the 17% of the population living in urban areas. As the country is rapidly developing, the demand for new houses and settlements is enormous. Addis Ababa, the capital, is growing extremely fast but the inadequacy of the local urban planning strategies is leading to critical situations in the city asset. Most of the times, to create new construction areas, the local municipality just demolish entire neighbourhoods and forces people to move into peripheral areas, careless about the community structures and connections, which are so very important in the Ethiopian culture. In fact, as the 80% of the people in Addis Ababa today lives in slums, informal settlements characterized by poor living conditions and services, the linkages between families are fundamental to ensure the survival of most of the households. This thesis aims to analyse the relationship between urban planning and informal settlements in the city of Addis Ababa, and to propose a new model for urban sustainable scenarios: finding ways to renovate the informal settlements but protecting the traditional community values. 2. Preliminary Analysis: Addis Ababa 2.1 Historical Background Addis Ababa was founded in 1886 by Emperor Menelik’s spouse, Empress Taitu, who personally chose the location for the new capital, near some hot water springs in the central valley of Shewa. Since its beginnings the city had a polycentric structure: the most important building was the imperial palace (the Gebbi) which was protected by other landlord’s palaces, strategically located by the emperor on top of the many hills which characterized the territory. Before the end of the century, two important events (a period of famine in 1892 and the victory against the Italians in Adua in 1896) led to a consistent growth in the city population. Therefore, people started to build their own shelter with cheap materials near the focal points of attraction, the palace, the churches and the market (Arada), shaping the present city-structure: informal settlements surrounding few main anchor points. From 1925 to 1930 Addis Ababa went through a period of fast modernization, with the construction of new roads, schools and hospitals. In 1930 the new Emperor Haile Selassie was coroneted but soon forced to leave because of the 1936 invasion by the Italian troops, which caused huge damages to the city. Mussolini, to elevate Addis Ababa to its rank of international capital, announced an international competition for a new city master plan. The winning project, by the Italian architects Guidi e Valle, was based on the concept of segregation between the local population and the colons fled to the new world, but only a small part is implemented, due to the beginning of the II World War: in 1940 Italians left the country and Addis Ababa remained a huge unfinished construction site. In this way the city got to keep his polycentric structure of a true independent African capital, escaping the destiny of many others, forged by the colonialist segregation. On one side being independent has permitted to protect the typical “social mixity” of the settlements and to not have ghetto-slums, but on the other side it complicated things a lot, in particular for the local administrations to manage the incoming expansion of urban population and territory. 2.2 Urban Profile 2.2.1 Environment The town lies at the foot of Mount Entoto, rising from 2326mt altitude on the southern outskirts near the airport to more than 3,000mt of the northern area. During the year there are two rainy seasons: the short rains from March to April and the long rains from June to September. The city is characterized by the presence of many rivers and an extraordinary morphological diversity. In recent years, Addis Ababa has undergone profound transformations due to the strong urban growth, which has resulted in tremendous pressure on the environment and natural resources. For example, as there is no system for the collection of municipal waste, more than 35% of the waste is discharged into rivers, streams or drains, causing health risks and environmental huge for the community. The situation is even more dramatic regarding sewage management. Only 7% of the houses are connected to the municipal sewerage system and 25% of residents do not have access to any kind of toilet, in most cases the sewage is simply dumped in rivers or streams. This system has caused severe impact not only on agriculture, but also on public health, since approximately 15% of the population has no access to public water supply and uses daily river water for washing. 2.2.2 Population Addis Ababa is one of the fastest growing cities in Africa: in 2005 had a population of about 2,973,004 people. Today it is estimated that the figure is around 4 million, 54.2% women and 45.8% men. A quarter of the population is under the age of 15, suggesting a high fertility rate. Young people from 15 to 24 years are 30% of the population and only 5.4% of the people reaches and exceeds 60 years. In the city coexist peacefully more than 80 nationalities and languages, with Christian religious communities Orthodox, Protestant, Muslim and Jewish. People belonging to the same ethnic groups tend to live in the same areas of the city: in fact, since the foundation of the city, the sefer (the original neighborhoods) were divided as per the ethnicity of the inhabitants. Addis Ababa is an ethnic mix of people from every corner of the country. The high rate of migration from the countryside, together with the rapid natural growth of the population, on one hand has exacerbated some of the problems already present (lack of housing, inadequate and inefficient infrastructures) and on the other hand has generated new problems such as high unemployment and urban poverty. 2.2.3 Administration The city of Addis Ababa has the dual status of city and state; the mayor is the chief executive of the city government. The town is divided into ten Sub-Cities or municipalities, each of which represents some 400,000 inhabitants. Each Sub-city is further divided into ten Kebele, or neighborhoods, each of which is about 40,000 to 50,000 people. The Kebele is the ultimate administrative body with responsibility for education, health and upgrading activities at the neighborhood level. The measures are discussed in meetings open to the whole community, which in this way is constantly involved in the decisions making process. However, due to the lack of support from the central government and scarce funds for urban planning and services, both the Sub-Cities and the Kebele have great difficulty in carrying out their duties in an efficient manner. These factors, together with the complexity of the bureaucratic system, legacy of the Communist regime that ruled in the seventies/eighties, cause congestion and poor efficiency in all types of interventions. Another important aspect to consider is the fact that the Kebele are often used as an instrument of political control by the government, through the management of building permits, business licenses and access to municipal services. 2.2.4 Society Most African cities grew during the colonial period, have an urban structure that reflects the division between the modern city of white colonists and the settlements of the indigenous population. Addis Ababa on the contrary, is characterized by an urban mix, both socially and architecturally, where the rich and the poor live in close contact. This is called social mixity, and is considered the distinctive character of the city, a traditional heritage to be safeguarded. The networks of social interactions are a priceless asset for the population: they can be compared to public institutions or social services, with the difference that they are based on the relationships between individuals or groups within the community. In Addis Ababa the 85 .4% of the population is part of an association. Most of them are registered to Iddir, voluntary non-profit organizations at the neighborhood level that help its members or their families in the organization of funerals. Other types of associations are based on religious belief (15%) or micro-credit (9%). The abundance of associations and groups distributed on the urban territory, especially in informal settlements, indicate that the population is active and committed. People are the greatest asset of Addis Ababa, for this reason promoting community participation in urban upgrading is not only recommended but may be the factor that determine the success of the project. 3. The Slums global phenomenon 3.1 What is a slum? The word slum is used to describe the informal settlements within a city, characterized by extreme poverty and inadequate housing. Slums are overcrowded urban areas which lack basic municipal services, such as water supply, electricity, sewerage, street lighting and asphalt roads for emergency access. Most of the residents of a slum have no access to schools, hospitals or public spaces. UN-HABITAT defines a slum as an area in which is verified one or more of the following deprivations: Inadequate access to safe water; Inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure; Poor structural quality of housing; Overcrowding Insecure residential status. 3.2 Slums in Addis Ababa In Addis Ababa the urban population living in slums is globally at the highest levels but the problem does not concern just the poor population: of the 80% of the population that lives in slums, only 45% are considered poor, while the remaining 35% belongs to the middle class. Another problem is the small size of housing units: 75% of the houses are less than 40sqm, while the remaining 25% are less than 20sqm, which is definitely not sufficient, considering that a household is constituted of 5.5 individuals on average. The structural conditions of most of the houses are poor: 75% of the houses have roughly made adobe walls, 25% have no bath, 27% have no private kitchen, 50% of the floors are made of clay, the rest covered with linoleum or bare concrete and roofs are almost always in corrugated iron sheet. Regarding the urban asset, the slums in Addis Ababa have different morphological characteristics depending on whether they are part of the historic core of the city or the suburbs. The settlements of the city center have a more regular structure: they are organized on a network of secondary roads, mostly unpaved, which delineate the boundaries of the compounds, protected by sheet metal fences supported by poles of eucalyptus. Within these compounds take place from two to five houses, organized around a common courtyard paved in stone or clay, in which most domestic activities are carried out. The outlying settlements rather have a more irregular structure as they are the result of decades of spontaneous aggregation: the houses are built mostly with natural or recycled and most of the times there are no fences. Many of these settlements are located in vacant lots within the city or along the banks of rivers or streams. To understand the dense web of social relations and the implications that have on the slums asset, I conducted a campaign of interviews on a small sample of slum dwellers. The results showed that the courtyard is much more important than the house itself: the open spaces are crucial for the implementation of the daily activities that cannot be done inside. In fact the houses are small, often made of a single room, so it would be impossible to do things such as washing, drying clothes or cooking inside, in addition to the traditional activities such as drying spices, shelling and grinding grain, killing and skinning animals for religious celebrations. The other important place for social gathering is the road: the formal business activities take place in small shops along the neighborhood fences, while directly on the walkways you can find the informal traders, mostly women who sell the few products of their garden and shoeshine boys. Along the main road also take place the animal’s market (mainly sheep and goats), arranged with rudimentary structures of eucalyptus poles with plastic awnings, to protect livestock from the sun or rain. Also on the streets and walkways are often organized important events for community life such as weddings or funerals: in both cases, huge tents are set up with benches and tables where guests gather to mourn the deceased or to congratulate the newly wed, sipping a cup of coffee. For these reasons an effective slum upgrading project must necessarily take into account the importance of outdoor spaces for slum dwellers, promoting regeneration trough respect and enhancement of the activities that usually take place in these areas, with new organizational forms that facilitate development. 4. The project The chosen area of intervention is located in the Bole Sub-City, near the southern border. The reason why I chose this area is the presence of two small informal settlements in a general context of formality, completely disconnected from the rest of the urban fabric. The open land that surrounds them is used occasionally to graze livestock by local shepherds. The approach chosen is to protect the structure of the spontaneous settlements, improving infrastructures and services and also providing guidelines for future expansion. In this way the demolition of settlements is avoided, protecting the network of social relations and creating the conditions for a sustainable densification. 4.1 Urban Analysis The urban analysis is divided into four parts: Viability: the main roads network stops at the beginning of the project area, which is crossed by a series of pedestrian informal paths. One of the key points of the redevelopment project is to improve the accessibility of the area, and then reconnect to the network of main roads on the outside. Urban fabric: the two problems identified are the lack of integration between formal and informal settlements and also the lack of integration and coherence among the informal settlements. The upgrading process will have to find solutions to reconnect the two different types of tissue, leading to confrontation at the street level and find a solution to facilitate the gradual approach between the two informal settlements. Zoning: the area is mainly residential and commercial activities are facing the main roads. There is also an industrial area along the Ring Road and two smaller factories both at the north and south border. The aim is to propose a redevelopment that fosters the integration of functions, to make the area better equipped and more liveable. Green system: the area is crossed by the river Kabana, a seasonal stream which is an important resource for local residents. The upgrading project makes the river Kabana an important anchor point for the community, with space for family orchards along the river banks. 4.2 Concept These are the four stages of upgrading outlined: The first step is the creation of a main axis connecting the two settlements, for pedestrians and light transport, which crosses the project area connecting it to the main road network and identifying future directions of expansion. The second step is to define a number of radial routes connecting the main road network with the new axis. Where the two paths converge, the "social anchors" are placed: they are spaces for business and social functions, with light wooden structures to protect from bad weather conditions. This means a connection between the orchards area near the river and the informal settlements, enhancing the sale of local products for the community, also promoting social encounters and increasing the livability of the neighborhood. The third step involves the creation of a secondary network of paths that cross and connect both settlements, in order to facilitate their accessibility and permeability. Also the new expansions area between the markets and the orchards is defined, setting the directions for the subsequent densification. Each of the areas between the new radial routes represents a new “urban upgrading unit”. The last step is the densification of the urban upgrading unit: the new buildings grow spontaneously and gradually along the new paths network. 4.3 Final Outcomes The urban upgrading unit is identified with a small community of about 600-850 people. The community is the lowest level both from the administration (Kebele) and the social point of view (association). These are the four key points of upgrading proposed: Increase accessibility : the network of informal paths is regularized, the existent paths are paved and equipped with street furniture; Integrate residential fabric with social anchor points: these are identified with the market structures that follow one another along the main axis. These structures can also be completed in different ways to accommodate a variety of functions, always related to the community needs (weddings celebrations, assemblies and funerals); Increase residential standard: each person is given 10sqm indoor and 10sqm outdoor. Therefore a family of 7 people must have a lot of 140sqm. The layout of the rooms in the compound is variable but consistent with traditional modes of aggregation around the courtyard. Improve sanitary conditions: a waste collection network is arranged along the two radial routes that border the upgrading unit. This network runs through the markets and the expansion zone and ultimately is conveyed into Phyto-treatment systems near the river which purify the water, which can then be used for agriculture. 5. CONCLUSIONS This thesis is intended as a proposal with guiding principles for urban development in cities plagued by the problem of slums. The strategy outlined in this project is to start from the redevelopment of the existing settlements, paving the way for future growth but also leaving the people free to find the most appropriate form. The objective is to give new living standards and equipment that can be reinterpreted in the manner and with the aggregative forms related to the culture and traditions of the country. REFERENCES M.Angelil and D.Hebel, Cities of change - Addis Ababa: transformation strategies for urban territories in the 21st century. Berlin: Birkhauser, 2010. G.Fasil and D.Gerard, Addis Ababa 1886-1941: the city and its architectural heritage. Addis Ababa: Shama Books, 2007. E.Yatbarek, Revisiting Slums, Revealing Responses - Urban Upgrading in Tenant Dominated Inner-City Settlements of Addis Ababa. Trondheim: Ph.D Thesis NTNU 2008:59. Dept. of Urban Design and Planning, 2008. UN-HABITAT, Situation Analysis of Informal Settlements in Addis Ababa - Cities without Slums Sub-regional Programme for Eastern and Southern Africa - Addis Ababa Slum Upgrading Programme. Nairobi, 2007.