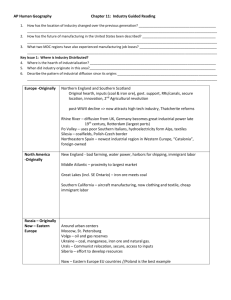

Thesis

advertisement