Remington_inequal & soc contract-final

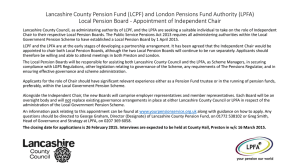

advertisement