C2014-0005 - Animal ethics approval

advertisement

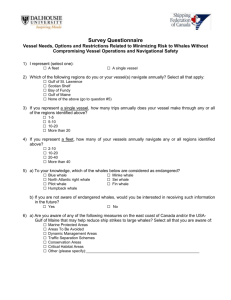

Ethics Application Mitigation measures to reduce entanglements of migrating whales with commercial fishing gear Background Whale entanglements are a key performance indicator (KPI) for the WRL fishery in Commonwealth assessments. Entanglements in 2013 (18 in WRL gear) exceeded this KPI for the third year in a row. The KPI breach in the proceeding season (2012, 13 entanglements) resulted in the Commonwealth removing the WRL fishery from the List of Exempt Native Species which is a five year export approval without conditions and issuing a two year Wildlife Trade Order (WTO) with conditions and recommendations relating to whale entanglement. This included a condition to : "by 31 March 2014, complete a robust evaluation of longer term operational management measures to reduce the risk of whale entanglements, which could include the removal of some restrictions on western rock lobsters, spatial and seasonal closures and potential gear modifications". The WRL is almost exclusively an export fishery with an estimated annual GVP of $200 million. The reason for increased entanglements is a combination of whale population growth (10% p/a) (Bannister and Hedley 2001, Salgado Kent et al. 2012) and an increase in winter fishing resulting from a relaxation of input controls after a move to quota. A closed season, removing winter fishing would somewhat alleviate this issue, although at an economic cost to the industry as it would no longer be able to attain the high beach prices paid in winter. This would result in a conservative loss of about $50 million p/a in GVP. Therefore to meet the Commonwealth conditions, and still allow winter fishing, entanglement mitigation measures are needed. Increased information on whale migration patterns is critical to the appropriate designation of times/area where gear modifications or spatial/temporal closures may be required. Currently, in the absence of these data, fishers are required to use gear modifications throughout the fishery (~1000 km of coastline), for the duration of the whale migration period (~7 months, May-November). With new information, the area/time where gear modification must be used could be refined, reducing costs to fishers in modifying their gear by only requiring modifications where/when entanglements are likely to occur. Collaboration This is a collaboration between government (DoF; Department of Parks and Wildlife), national research bodies (Australian Antarctic Division (AAD), Murdoch University Cetacean Research Unit (MUCRU)) and industry (WA Fishing Industry Council – WAFIC and Western Rock Lobster Council). Objectives 1. Produce fine-spatial and temporal information on whale migrations along the west coast of Western Australia necessary for a tailored spatio-temporal closures and/or areas for gear modifications. Procedures This project uses a combination of procedures: Telemetry : The use of blubber/fascial-implanted satellite tags is the least invasive way of tracking whales reliably. Alternative implantable tags are available but are significantly longer and penetrate deep into the muscle layer. The satellite tags are deployed via a modified pneumatic line-thrower from a distance of 4-15m. The tag penetrates the whale’s skin and blubber until it reaches the stopper at the end of the tag. A flexible transmitting aerial extends about 17cm from the top of the tag. The positioning of the tag is into an area just below the dorsal fin giving the aerial maximum time at the water’s surface. The tag is designed to transmit for a period ranging from weeks to months. The tag will fail due to electronic malfunction, battery exhaustion or eventually tag rejection. Due to the superficial application of the tag, it will eventually be rejected or simply fall out, usually within 6 months (Double et al. 2012). This is a common method of satellite tracking cetaceans and has been used successfully before on humpback whales (Double et al. 2012). All attempts and actual tag deployments are videotaped, and the tape is reviewed each day. Videos will be available for review by regulatory agencies. Biopsy: Biopsy samples are collected to ascertain the sex of the tagged individual allowing sex based movement patterns to be determined. There are marked differences in the migratory patterns of male and female humpback whales (Brown et al. 1995), and therefore biopsies will permit a critical examination of this. However, biopsies will also be retained and stored for possible examination as part of future research work, where biological samples may be useful. The skin biopsy is darted using a modified capture rifle (0.22 calibre supplied by PaxArms, Timaru). This is a non surgical procedure and involves only brief and minor disturbance to the behaviour of free-ranging whales. Biopsy sampling has been successfully used previously on this species (Brown et al. 1995, Double et al. 2012). The biopsy dart is a small stainless-steel punch fitted to an arrow or small (50 cc) floating syringe and deployed from a capture rifle. The size of the tip of the dart which collects the sample is between 4-8mm in diameter (dependant on the tip selected) and the dart is about 30mm in length. A metal flange or stop which sits behind the dart tip is approximately 2-3cm in diameter and prevents penetration of the dart beyond 5-6mm into the skin and blubber and provides recoil to dislodge the dart on contact with the whale. The actual biopsy sample removed is approximately 2-3mm in diameter and 5-6mm in length (slightly bigger than a rice grain). In some cases the dart may be tethered for retrieval. The force of the impact is adjusted via an adjustable gas vent. The dart can be deployed from a distance of approximately 5-20m. The biopsy dart is cleaned and sterilised by flaming after each collection and immersed in 70% ethanol before use. Approaching whales for tagging / biopsy Each whale is approached in a 5.5m rigid-hulled inflatable boat (or similar platform) to facilitate the deployment. Strict protocols are followed to ensure that the whale is not unduly harassed during the deployment. There are two methods of deployment employed for humpback whales: Fast approach: initial approaches are slow and are ceased if the whale actively avoids the boat. Once in position, a single rapid approach is made to the whale during a surfacing and the tag is deployed. If the tag is not deployed during this fast approach, further approaches are only attempted if the whale continues to be unconcerned by the movements of the boat. Avoidance behaviour by the whale is used to signal the animals’ level of concern, and determines whether the attempt is terminated. Fast approaches will not be made on animals or groups with calves. Slow approach: where possible, drift approaches (from upwind) will be made on whales that are resting on the surface. A tag will be deployed once the whale is within the required range. Females with calves will not be excluded from this group as ‘slow approaches’ are relatively straight forward with the potential for impact on the calf is negligible. Furthermore, information on the movement of cow-calf pairs is of particular management relevance due to likely differences in movement patterns of females accompanying calves. Experience and Training Tagging and biopsy techniques will only be carried out by trained and experienced researchers. All personnel involved in these procedures will have been trained by experienced researchers familiar with the equipment and methods used having participated in multiple field trips. This initial training and knowledge transfer will be facilitated through the involvement of staff from Australian Antarctic Division and Blue Planet. Level of experience does not necessarily affect the targeted whale – if a person misfires, the tag or biopsy dart will either not fully implant and promptly fall out, or, will miss the animal entirely. There is little additional risk to the animal. Conclusion: Through satellite tagging a small portion of migrating humpback whales we can gain a valuable insight into how these animals utilise the waters of the WA coast. This data is not available through alternate means and hence, through the use of a common, minimally invasive procedure, we can gain valuable information to mitigate interactions between commercial fishing gear and migrating whales. Any effect from satellite tagging is minimal compared to some of the effects of long-term entanglement. Therefore, this data can result in a considerable net benefit to the welfare of this whale population. Rick Fletcher Executive Director (Research) / / 2014 APPROVED / NOT APPROVED