File - Susan Stevens

advertisement

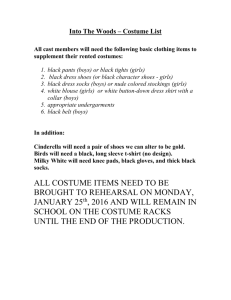

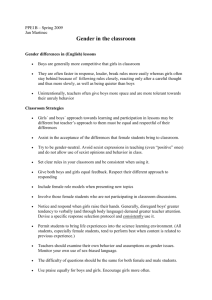

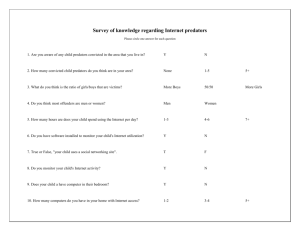

Entering Book World How do We Help Both Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? Susan Stevens EDU 600: Teacher as Leader Module 8 Assignment June 20th, 2011 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? When teaching reading, I want to help my students enter Book World, which is that magical place where you are so immersed in what you read that you enter the story and lose track of time. To create life-long readers, I need to help my students enter Book World, or what Jeffrey Wilhelm calls “flow. . . a total immersion in the immediate experience of reading. Indeed this kind of immersion is the basic fact of engaged reading” (Boltz, 2007, para. 3). Boltz also makes the point that boys tend to enter the flow through different types of literature than girls— literature which generally don’t make it to the teacher’s preferred reading material list (2007). Therefore, book choice is the key to entering Book World. I can learn about my students and make book suggestions that lead them to Book World individually; I can give literature circles preference choices that usually lead them to Book World—but what about class read-alouds? What can the literature tell me about how I can I better select books that will help me hook both boys and girls at the same time, helping them enter Book World, while at the same time providing strong role models for them? This is important, because if we don’t hook readers early, our students may develop a life-long aversion to reading (Merisuo-Storm, 2006). The “Boy Crisis” and Book Choice There is a lot of literature about the “boy crisis” in reading. It seems that boys test lower in reading almost universally (Boltz, 2007; Charles, 2007; Sadowski, 2010; Schwartz, 2002; Sullivan, 2004), especially in the area of comprehending narrative text (Schwartz, 2002), and this lower reading level affects their performance in all subjects (Sadowski, 2010). There’s evidence that boys read less than girls which directly connects to their level of reading fluency (Boltz, 2 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? 2007; Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Sadowski, 2010; Sullivan, 2004). Boys also tend to see themselves as poor readers (Boltz, 2007). A number of reasons are given for the “boy crisis” in reading: There is negative peer pressure as boys struggle to be viewed as masculine (MerisuoStorm, 2006; Watson, et.al., 2010). Negative attitudes are contagious (Merisuo-Storm, 2006), which makes it important to identify and hook those students with negative attitudes first, before the disease spreads. Boys do not have enough male models which is highly important as attitudes about reading develop early (Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Schwartz, 2002; Sullivan, 2004), especially in the area of viewing reading as recreation (Boltz, 2007). Boys tend to read brief, informative texts (Boltz, 2007; Schwartz, 2002; Sullivan, 2004), where classroom read-alouds tend to be narrative. Boys prefer non-fiction, comics, how-to manuals, graphic novels, sports, adventure, fantasy, humor, horror, and series books (Boltz, 2007; Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Schwartz, 2002; Sullivan, 2004). Part of the appeal of series books is that boys can guarantee that they don’t accidentally pick out a “girl book” (Merisuo-Storm, 2006). This is information that we can use. If we can hook boys on a series they’ve got a reading plan laid out for a while. Some studies show that boys are hard-wired to enjoy action books because they have less cross-hemispheric activity, thus needing an extra “jolt” in their reading (Boltz, 2007; Sullivan, 2004). Teachers and librarians tend to treat “boy books” as sub-standard literature; we need to promote them in book talks (Sullivan, 2004). General Gleanings From the Research 3 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? We need to hook boys [and girls] on reading first and then move them toward “better” quality literature (Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Sadowski, 2010; Sullivan, 2004). At the same time, we need to teach students that they may prefer a lighter book when they have a cold, when they’re upset about something, or just when they’re feeling tired. Their reading doesn’t need to march relentlessly uphill as that does not reflect real-world reading. Since girls tend to dominate class discussions, we need to involve boys in class discussions to help them comprehend and think analytically about what they read (Schwartz, 2002). One way to promote participation is through written discussion, either in pairs or small groups and either on paper or on the computer. We teachers must broaden our genre repertoire if boys are to be pulled in, as reading instruction most often takes place with narrative fiction and boys more often prefer to read for practical purposes (Boltz, 2007). As an aside, students also need to be taught to read multidirectionally, a skill used when they read electronically with hypertext and multi-media (Boltz, 2007), a skill that many teachers ignore. Storytelling appeals to struggling readers and since boys make up 70% of the students in remedial reading classes (Sullivan, 2004), storytelling is a worthwhile addition to the teacher toolkit as both a teaching technique and an assessment technique. Even more than girls, boys need read-alouds (Boltz, 2007; Sullivan, 2004). That’s good news to me as I use read-alouds for my strategic teaching via “think-alouds.” This year we read twelve full-length chapter books, but the question still remains--which books will best engage both boys and girls. 4 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? It seems that boys read more genres than girls (Schwartz, 2002), but are more selective (Merrisuo-Storm, 2006) generally in terms of whether a book is a boy book or not. Girls tend to cross gender lines more easily (Merisuo-Storm, 2006). One study showed that the top three choices of boys and girls are the same three genres—comics, humor, and adventure—just in a different order (Merisuo-Storm, 2006). It would seem logical, then, to start the school year with one of these genres. Although girls read more than boys, and are more interested in books that have to do with internal reflection and that emphasize emotions and interpersonal relationships (Boltz, 2007; Sullivan, 2004), it seems that much of what interests girls is superficial in nature like fanzines (Boltz, 2007) and romance (Charles, 2007). Little of this reading provides role models for girls that are self-determinate, flexible, responsible, and/or empowered (Charles, 2007). In the same way that I mentioned about boys, girls need to be hooked on reading first, and then moved toward better quality reading material. As teachers, we need to be aware that preferences and interests are not always the same (Boltz, 2007; Merisuo-Storm, 2006). A student may prefer reading humor to science fiction, but not be interested in either. Thus, our highest priority must be uncovering the interests of each of our students. I model my love of reading by bringing in my reading stack and show my students the variety of reading. I often import men as positive reading role models for my students. These men give book talks and read with my most resistant readers for a class period a week during the school year. On the whole, we need to provide real choice (Boltz, 2007; Merisuo-Storm, 2006; Sullivan, 2004), a well-stocked classroom library (Boltz, 2007; Schwartz, 2002), and have 5 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? students organize the library which encourages greater use of the library (Boltz, 2007). Also, time for free voluntary reading is the key to a successful reading program (Boltz, 2007). Applying the Research One suggestion that I appreciate is to think and act locally (Sadowski, 2010). Since every school and every class in that school is different, and what works for one may not work for another, we need to be reading detectives in our classrooms. To that end, I used the current Measurement of Academic Progress® (MAP®) testing data for our school and broke it down into male and female categories to take a look at gender differences. The students tested are upper income, and from 40 different countries, although Ecuadorians, U.S. citizens, and Koreans predominate. Students have widely varying proficiency in English, many students are trilingual, and so may be proficient in their maternal tongue, but not in English. Student Performance by Gender in Reading According to RIT Score: Grade 2 - 10 MAP Testing RIT band 161-170 171-180 181-190 M Total 201-210 211-220 221-230 231-240 241-250 M M M Number of students per grade in RIT band Class 2nd grade 3rd grade 4th grade 5th grade 6th grade 7th grade 8th grade 9th grade 10th grade 191-200 F 1 1 M F M F M F M F 2 2 2 3 1 4 1 2 1 2 1 2 2 5 2 2 2 1 3 7 5 9 6 7 F F Total 18 1 Total 14 5 3 2 1 Total 24 4 2 3 1 1 Total 12 1 2 2 3 2 Total 11 1 2 3 Total 11 Total 6 Total 15 1 2 F 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 5 2 1 2 1 3 4 2 2 1 Total 16 12 11 13 14 5 4 2 Total 127 1 1 F 1 2 1 M 15 5 8 6 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? As far as the school is concerned, 18% of the students test below grade level—about 70% of which are boys. With such a small sample size, I’m not sure how statistically important these figures are. Thinking even more locally, the “boy crisis” is not evident in my upcoming class which has six boys and seven girls below grade level, five boys at grade level, and four boys and two girls above grade level. Instead, I can anticipate a general reading crisis as my upcoming class has several students with severe learning disabilities and a number of students in their first year learning English. The research validates a lot of how I structure my reading: lots of read-alouds and storytelling, and time for free voluntary reading. Guided reading is designed to move students toward more difficult and/or more literary reading. Even in guided reading, I try to include a preference choice so students are empowered. As a result of this study, I will make sure to purchase and publicize a wider variety of “boy books” and “girl books” in my classroom library. I’m also going to look into the growing genre of narrative non-fiction and more books of the slightly gross humor variety. Yes, I even found myself purchasing a book about the Jonas Brothers for one of my female readers who needs to be hooked. From what I’ve read, I need to hook my boys first, and I believe the fantasy genre has a lot to offer both boys and girls. Specifically, I’ll begin the year with a fantasy unit with components designed to hook all students. I’ll choose something like Harry Potter, with strong male and female characters who fight evil. Using these books, I can read a chapter and then show a portion of the movie with subtitles to help my ELL students build background knowledge and also help those students who have trouble visualizing. I’ll do single-gender guided reading 7 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? groups with “girl fantasy books” that may have a bit more romance and “boy fantasy books” that may have a bit more action. Discussion will take place on Edmodo and on paper for guided reading groups and be whole group for the group read aloud. The literature confirmed gut feelings that I’ve had about boys and girls preference and validated some practices I tried last school year such as focusing more on hooking the boys in the class at the beginning of the school year as girls tend to cross over gender lines with their reading. It also is pushing me to broaden my classroom library. 8 Entering Book World: How Do We Best Reach Boys and Girls in Class Read-Alouds? References Boltz, R. H. (2007). What we want: Boys and girls talk about reading. School Library Media Research, 10, (no page numbers given) Retrieved from EBSCO host. Charles, C. (2007). Exploring "girl power": Gender, literacy and the textual practices of young women attending an elite school. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 6(2), 72-88. Retrieved from EBSCO host. Merisuo-Storm, T. (2006). Girls and boys like to read and write different texts. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(2), 111-125. doi:10.1080/00313830600576039 Sadowski, M. (2010). Putting the "boy crisis" in context. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review, 76(3), 10-13. Retrieved from EBSCO host. Schwartz, W., & ERIC Clearinghouse on Urban Education, N. Y. (2002). Helping underachieving boys read well and often. ERIC Digest. Retrieved from EBSCO host. Sullivan, M. (2004). Why Johnny won’t read. School Library Journal, 50(8), 36-39. Retrieved May 29, 2011, from ABI/INFORM Global. Watson, A., Kehler, M., & Martino, W. (2010). The problem of boys' literacy underachievement: Raising some questions. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(5), 356-361. Retrieved from EBSCO host. 9