Report on University Travel Scholarship and Ede & Ravenscroft award

advertisement

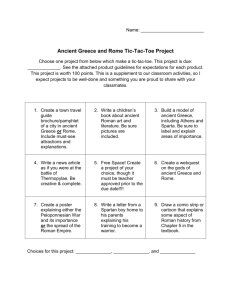

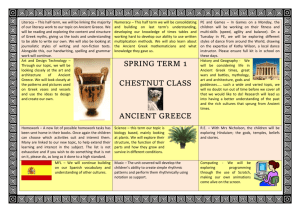

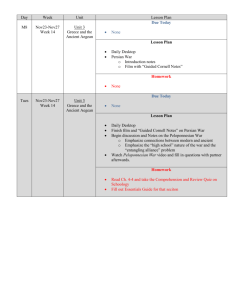

1 Report on University Travel Scholarship and Ede & Ravenscroft award by Kimberley A. Harman (BA Ancient History & History, Year 3) I applied to go on a summer school with the British School at Athens, which lasted for three weeks and included visits to around fifty sites which are important to the study of ancient Greece. I received £400 from a Sheila Spire scholarship, and £300 from the Ede and Ravenscroft fund. This paid the BSA course fee of £590 and most of my flight cost, which was £180. I only had to provide the recommended spending money myself, which was for food, basic needs and any extras we wanted. In my Ancient History and History course, I have chosen Greece as my focus, mostly during the Classical and Hellenistic eras, with some knowledge of the later involvement of Rome. Some of the sites on the course itinerary were very familiar to me; the Parthenon is iconic of the ancient world, and places like Sparta and Delphi are mentioned in almost every textbook. But what was perhaps most important was visiting sites which were entirely new, and attending lectures which focused on the Bronze Age or earlier, eras which I have never studied before. A familiar picture of the Parthenon. This extra information gives me a good overview of parts of history which I have overlooked, and a better background to the areas I want to study further. Some of the information was so intriguing that since returning to England I have put some extra time into reading about places and cultures I might otherwise never have looked at. Each student was given a booklet at the start of the trip. It contained maps and plans which admittedly made little sense to us on the first day. But upon arrival at each site, the layout of the ruins began to match the diagrams, and I could see what each room was used for, and how important each temple, palace or settlement might have been. The lecturers led us through each place as if the building were still completely standing, which made it much easier to The types of maps we used. This one is the Palace of Nestor at Pylos. visualise than looking at a two-dimensional photograph would. For example, the only remains of the Palace of Nestor in Pylos are some parts of the walls, as is the case with many other sites which we saw. But then we were taken through where the front door once stood, and were led through the palace in the way a visitor would have been when the building was in use. After visiting a few sites and using this method, small things 2 become noticeable and you start to recognise them as important evidence for finding out about the use of the building. A drainage system and a sloped floor instead of steps might indicate that animals were brought into a temple for sacrifice. A site on top of a hill might have been placed for defensive reasons. Two temples placed near each other might suggest a connection between the two gods or heroes they were dedicated to; and so on. For me, the most valuable aspect of the trip was to give me a more informed perspective on the study of the ancient world. As a student who mostly focuses on written sources, I didn’t really grasp just how much archaeology can teach us until visiting the sites and the museums at each one. Up until now, I have relied on ancient texts, but seeing the places as they really are makes it clear that there is much more to the ancient world than that. Instead of just using the published or famous words of philosophers and writers, I feel that I am now in a better position to use all the information available to historians; temple layouts, inscriptions, grave monuments, coins, potsherds. It is literally incredible how much can be learned from the smallest piece of evidence, and this is much easier to investigate when you have seen an archaeological site rather than detachedly trying to gain a picture of it from a library, miles away. Sikyon, the archaeological site we visited, was a good example of this, and taught me much more about this type of evidence. Wherever we stood, there were sherds of ancient pottery around us. Although famous temples and beautiful statues have come to represent the ancient world, they are not the only way the past should be studied. Vast amounts of evidence survive, and it is very difficult to describe to someone who hasn’t seen it. Showing pictures of my trip to people has been somewhat frustrating; the great views, impressive buildings and the scale of the statues can’t quite be captured by a photograph, even though I had a camera with me at all times! A huge number of figurines all found in one place and displayed in one museum. I found it much more worthwhile to read about the places we had visited in the BSA library each evening, when I could clearly picture everything and understand what the author was describing. The same has applied now that I am in lectures again for my third year. When a lecturer mentioned a religious procession, I found myself picturing the road we took towards that particular temple, and while translating epigraphic evidence on a tombstone in the Kerameikos, I could remember the place where it stood. When it comes to buildings and inscriptions, the landscape and sites themselves are the contextual information you need. I also gained a lot more enthusiasm for the subject. While I have always been very involved in my degree, the fact that I limited myself to library study narrowed my vision of the whole area I am supposed to be looking at. With the added skills I picked up while visiting the sites, I feel that there is much more to my degree that I had not taken into account, and which I am looking forward to using in my work this year. After seeing these places and learning about them on site, I feel better prepared to use epigraphic or architectural evidence rather than just relying on words. A combination of the two is completely necessary for accuracy. Remains of the ancient world are in some ways more ‘pure’; they haven’t been translated or written from one person’s point of 3 view. They are clear, physical evidence, and supplement the written sources to give a full picture of the societies I have been studying. Seeing everything in its original context also gave me a sense of the continuity of the history of these places, rather than categorising everything by date. With every place we visited, the influence of each new era was clear. At some sites, there were elements which didn’t seem right, such as pillars which seemed to block the pathway, or things which didn’t fit with what we had already learned about particular types of building, such as rooms which didn’t belong in a certain type of temple. At this point you could see that one structure had existed in the Archaic period, and then been built over in the Classical, then Hellenistic, then later years. Although my trip was mainly intended to focus on learning about Classical Greece, I realised soon after arriving that studying one era would be neglecting important issues and themes. My specific area of study is inevitably intertwined with the time which led up to it, and the influence of later eras can’t be missed. Certain styles and images which became prevalent during the rise of Christianity were clear in several sites, and there were several places where the modern history of Greece was tied in with the country’s ancient past. We visited Sphakteria, an island where a battle between Spartans and Athenians took place in the classical era, but there were also modern monuments from the Greek War of Independence, which I have never studied before and know very little about. Being able to see one site where two famous events occurred, 2250 years apart, seriously brought home the fact that history should not be segmented and drawn into separately named ages, but is an ongoing development. There are always recurring issues in the present which have happened in the past, and A statue of the gods Hermes and Dionysus, on display at the Museum of Olympia. similarly history’s influence on the present will never die out; looking at one place which represents events spread over literally centuries makes this point absolutely undeniable. I returned to England with a heavily annotated book of maps and plans, over a thousand photographs, 29 new friends to share research and dissertation notes with, and a much greater understanding of the ancient world. I have a better picture of how things might have been, a more detailed idea of how we found out about it, new skills and methods for studying it, and greater knowledge about why it is important to uncover it in such great depth. I want to thank the University, my department, the Sheila Spire fund and the Ede and Ravenscroft fund for helping me to do this; it wouldn’t have been possible without a scholarship, and I know the journey will have a long lasting impact on my grades and my ambitions for further study. 4 The group of thirty students who took part in the summer school, near the Temple of Olympian Zeus.