07 - Gold

advertisement

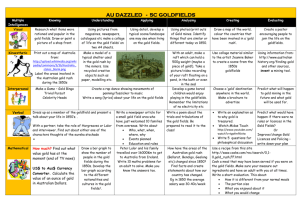

Australian History: Gold Many people believe that in 1851 Edward Hargraves was the first person to discover gold. This isn't true. Before 1851 gold had been found by convicts, shepherds, a clergyman and a Polish explorer. Hundreds more people probably found gold but did not bother telling others about it. Before the gold rush It may seem strange that some people could discover gold without others going to the area and trying to find it as well. But before 1851 this is exactly what happened in Australia. Gold was first discovered by James McBrien, a government surveyor, in 1823 in the Fish River near Bathurst. Then in 1839 Paul Strzelecki found gold near Hartley. In 1844 a geologist Reverend W.B. Clarke later found gold in a creek near Lithgow but upon agreement with Governor Gipps kept quiet about it, fearing that the discovery may spark violence a chaos amidst the community where the majority of residents were criminals. Additionally farmers and squatters were against a gold rush, as they were worried about their labourers quitting their lowly paid jobs to try their luck at digging gold. Governor Gipps has been quoted in many texts in response to the gold findings: "'Put it away, Mr. Clarke or we shall all have our throats cut!" In 1823 James McBrien found traces of gold near Bathurst, NSW. However, early discoveries of gold in Australia were hushed up by the authorities for fear that all the convicts, soldiers and public servants would stop work to hunt for their fortune. In 1841, the Rev. WB Clarke found a gold nugget near Cox's River in the Blue Mountains, NSW. When he showed the gold to Governor Gipps, the Governor said, 'Put it away, Mr. Clarke or we shall all have our throats cut!' It wasn't until ten years later, in 1851, that Edward Hargraves, (who had just returned from the gold fields in California) and his colleagues found gold near Bathurst. This time the find was publicised and within a month a thousand men were looking for gold. The area was called Ophir, after the biblical story about King Solomon's gold city. The penal system ended in 1840 and by the 1850’s the fear of a violent breakout as a result of the gold rush subsided. At the same time there had been discoveries of gold in California, USA, which saw a mass exodus of the population to search for it. This prompted Governor Fitzroy to promote the search for gold in 1849. In 1851, Edward Hargraves, who had spent 18 months working on the Californian gold fields returned to Australia, believing there was gold around Bathurst and Orange. Some reasons for why there was no gold rush before 1851 All gold found in Australia belonged to the government. There was not much point trying to find gold if it had to be handed over to the government. The discoveries before 1851 were not very big. Gold was mainly found in isolated places where the news did not spread very far. Only a few people in the colony knew where to look for gold and how to find it. Perhaps the government deliberately tried to stop news about gold from spreading. If they had a chance of finding gold, convicts might riot and would leave their work. How could the government control things then? The gold rush After a long trek on foot or horseback by coach or dray from Sydney or Melbourne, new miners were thankful and excited when they reached the goldfields. On the larger fields they saw hundreds or even thousands of tents clustered around creeks or near the site of earlier discoveries. There were horses and bullocks, wagons and carts and everywhere people bustling around, digging, panning, washing gravel, moving mounds of dirt or gently rocking their cradles from side to side. New miners soon realised, however, that the goldfields were not as attractive to live in as they looked from a distance. At Bendigo, for example, up to 40,000 people lived close together in tents. They did not have enough water and their toilets were simply holes in the ground. Garbage piled up around the diggings and even miners who were used to it found the smell impossible to work in. Miners worked hard day after day and often could afford neither the time nor the money to buy good food. Prices on the goldfields were very high, partly because all food had to be brought to the diggings by bullock teams and partly because traders knew the diggers had to buy from them or go hungry. Like the early squatters, miners lived on bread, tea and mutton. Only those who were lucky could afford luxuries. Miners often became sick with diseases caused by bad food, poor living conditions and the effect of working outdoors in all kinds of weather. The first diggers lived in tents which they brought with them to the goldfields. They were cold in winter, hot and stuffy in summer and very uncomfortable when it rained. If it seemed that there was a lot of gold to be found on a digging, miners sometimes spent some time building a rough hut from bark or slabs, just as the early squatters did. The miners who took their wives and children to the diggings were usually among the first to build stronger homes. As well as diggers’ tents or huts, there were many other buildings on the goldfields. Stores, grog shanties, inns, government offices, post offices, gold-buyers’ huts and later, theatres and public halls appeared. Getting a licence At first the government did not know quite what to do about the gold diggers. Should they be allowed to go wherever they like and dig wherever they wanted? How could roads and bridges be built quickly enough for the diggers to move about? Where were the wages of goldfields’ policemen and officials going to come from? Who would pay the escorts who traveled with coach loads of gold and tried to protect them from bushrangers? The government decided that the best way of controlling diggers and, at the same time, raising money was to make each miner buy a licence. This cost was 30shillings each month. Thirty shillings was quite a lot of money for the time and it was not easy for diggers who had found little or no gold to pay for their licences. Miners thought it was unfair that those who had not found gold had to pay the same as those who had found a lot. They hated the way the goldfields' police - 'traps' they called them - checked that the diggers had bought their licenses. The police were often brutal, dishonest, unfair and inefficient. The miners' distrust and hatred of the police was to cause serious trouble on the Ballarat goldfields in 1854. Finding gold There are two main types of gold. Alluvial gold is the gold found as small flakes, nuggets or dust. Buried gold is found beneath the earth's surface. Alluvial Gold This gold was once buried below the earth’s surface. Over thousands of years, rivers and creeks slowly wore away rocks containing this gold until the gold washed away rocks containing this gold until the gold washed away and settled at the bottom of them. Diggers found gold flakes and small nuggets when they washed dirt and sand from old creek and river beds. Buried Gold Once they had taken all the alluvial gold, miners started to dig in search of gold found in deep seams (‘seams’ means deposits of gold). The followed leads (‘leads’ means gold-bearing deposits of rock) down into the earth. At first, teams of three or four would dig shafts 30metres or more deep. Later, companies were set up to extract gold from reefs (‘reefs’ means veins of rocks) deep underground using heavy equipment and machinery. Panning for Gold The simplest way to find alluvial gold was to pan for it. To do this a digger needed: a pick to break up the soil and rock a shovel a panning dish to wash the soil and rock At first diggers used any round dish they could find to pan for gold. The best types were the wide tin dishes used in dairies to separate milk and cream. Soon tinsmiths began making special pans with a wide base and shallow rim. Some diggers used pan to see if the soil and rock they were digging up had any gold. Then they would use more efficient equipment to wash the pay dirt – the gravel soil and rock that contained gold. Life in the gold fields Working on the goldfields Most diggers worked from dawn to dusk, six days a week. Sometimes they were lucky and had a good strike. Often they found very little at all. Perhaps they made as much as the workers left in town, perhaps a little more or a little less. But they worked very hard indeed for what they discovered. Women and Children on the Goldfields Most of the people on the goldfields were men. A lot of them were bachelors but many did not think the rough and ready diggings were a good place for women to live. But, from the beginning, there were women who went to the goldfields with their husbands, brothers or friends. They shared all the discomforts of life on the diggings and worked as hard as the men: washing, cooking, chop- ping wood and helping with the search for gold as well. Other women travelled to the gold- fields later when their husbands had found enough gold to build more comfortable huts and send for their wives and children. They often kept a few hens and goats so that their children would have better food. As the number of women on the goldfields increased, life became more settled. One person wrote that 'the men are seen going to and fro, in a regular daily routine, to work, and back to their meals, and to their homes at evening'. There were other women on the goldfields. Laundresses took in the washing that men were too busy to wash themselves. Many storekeepers were women. Prostitutes, dancers and actresses drifted to the goldfields where they made a good living entertaining the diggers. Many children went to the goldfields with their parents and by December 1852 there were almost 12000 children on the Victorian diggings. Most of them spent their childhood helping their parents search for gold. They carried wood, looked after the tent or hut, cared for the horses and fossicked among the ‘tailings’ or left-over gravel and sand. Older children were expected to work as hard as adults. Some parent sent their children to school on the diggings. Goldfield schools started in tents, some of which were big enough to hold up to a hundred children, sitting at long wooden benches. The children’s parents paid a fee so that their children could go to school. As you could imagine the standard of education from these schools was not very high. Children moved from one goldfield to another. If there was no teacher there, they had to wait until one turned up. Teachers, like others on the goldfields, lived in tents. They had almost no equipment and if the pupils moved, the teacher too had to pack up and move to a new place. If a goldfield became well established and diggers stayed there for several years, more permanent or lasting schools were organised Fun and Games The diggers worked hard but there was time, at the end of the day and on Sundays for relaxation. At the Ballarat goldfields, a makeshift boxing saloon was created to accommodate weekly boxing matches. Grog tents, like a bar in a tent, were set up for drinking. At first hotels were not allowed on the diggings, but sly grog tents or shanties were disguised as coffee shops. They were often run by women and were especially popular on Saturday nights. Edward Hargraves Edward Hammond Hargraves (October 7, 1816–1891) was 34 years old when he discovered gold at Bathurst. He was born in Hargraves was born at Gosport, Hampshire, England and was known to have worked in many jobs such as a sailor, a farmer a hotel manager and a shipping agent. He was not successful at any of these jobs. Hargraves went to California during the California Gold Rush to try to make some money and again failed. He realised that the goldfields of California looked very much like some areas of New South Wales (the Macquarie Valley) which inspired him to return to Australia to prove gold could be found here. On February 12, 1851, Hargraves found gold near Bathurst, at Summer Hills Creek, he called the goldfield Ophir, named after the Biblical city, and the Ophir Township was later established there. He was accompanied on his prospecting expedition by John Hardman Lister and James Tom, but as soon as Hargraves found gold he went to Sydney alone. He announced his discovery and claimed a £10,000 reward for being the first person to find gold and claim it. He was also appointed Commissioner for Crown Land and the Victorian Government paid him £5 000. He only claimed £2 381 before the funds were frozen after James Tom protested. An enquiry was held in 1853 which upheld that Hargraves was the first to discover a goldfield. Shortly before his death in 1891 a second enquiry found that John Lister and James Tom had discovered the first goldfield. Hargraves was never a gold miner and instead made money from writing and lecturing about the Australian goldfields.