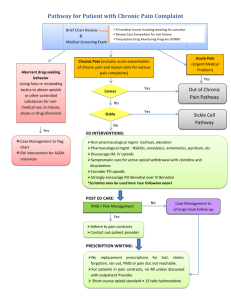

Box 2. Recommendations for acute pain care in EB

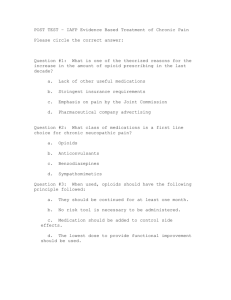

advertisement