Supplementary Material Supplementary Data Fig. S1

advertisement

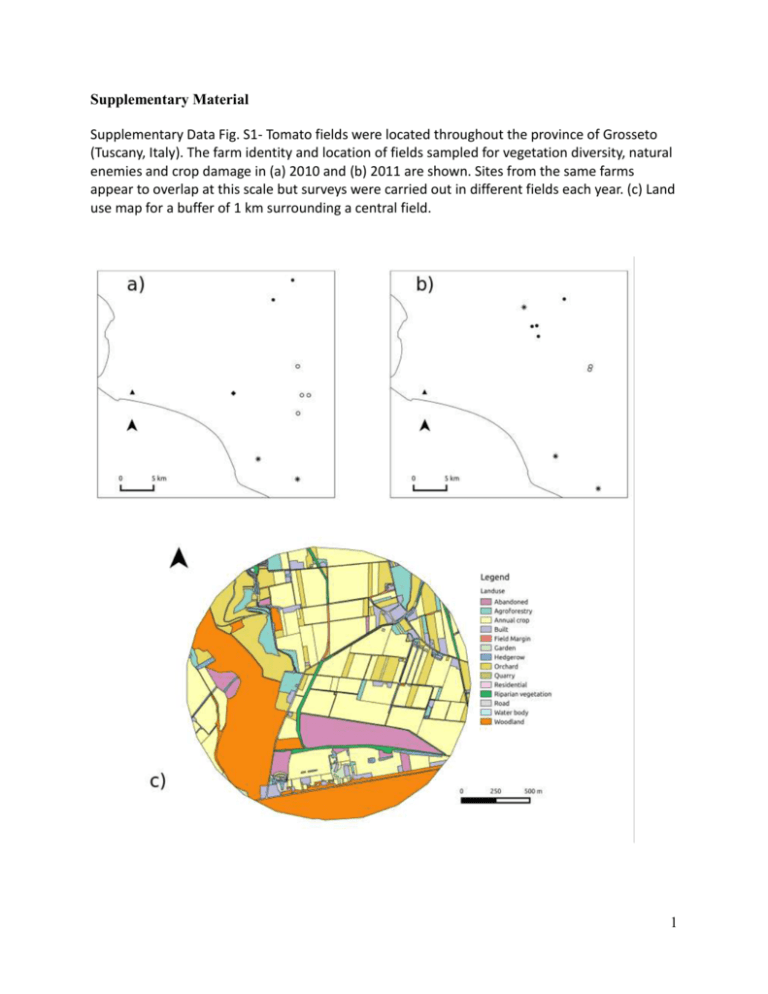

Supplementary Material Supplementary Data Fig. S1- Tomato fields were located throughout the province of Grosseto (Tuscany, Italy). The farm identity and location of fields sampled for vegetation diversity, natural enemies and crop damage in (a) 2010 and (b) 2011 are shown. Sites from the same farms appear to overlap at this scale but surveys were carried out in different fields each year. (c) Land use map for a buffer of 1 km surrounding a central field. 1 Supplementary data table S1 - Land use cover classification system used for the landscape analysis. General Category Urban and built-up land Land Use Categories Individual residential units (normally within an agricultural matrix) Large-scale residential areas (e.g. city centres) House and public gardens Roads and streets Agricultural Land Fields cultivated with herbaceous/annual crops (e.g. tomato, grain, maize, sunflower, potatoes, etc.) Olive groves or orchards with fruit trees Orchard which also include the cultivation of herbaceous crops (intercropping). Natural and semi-natural vegetation patches Herbaceous field margins (with width greater than 1.5m) Hedges (linear patches of closely spaced shrubs and tree species) Recently abandoned agricultural fields Woodland and maquis habitats and long agricultural fields which have been abandoned for a longer time (characterised by the presence of dense shrubs) Riparian vegetation Surface water bodies Streams, ponds, rivers and other surface water bodies. Ecologically Disturbed Ground Any other land use which is not included in the above and which is characterised by human disturbance (e.g quarries). 2 Supplementary Data Fig. S2: The full path analysis model for (a) richness and (b) abundance data. Percentage cropped land was used as a measure of landscape complexity and plant species richness in field margins as a measure of local vegetation diversity. Richness of predator and parasitoid groups was used to indicate natural enemy diversity, given that we have observed a positive effect of local vegetation diversity on predator and parasitoid abundance and this reduced the number of paths in the model increasing statistical power. Time of harvest and year, shown in grey boxes, were also included as exogenous variables, while all other factors in black boxes are endogenous variables. The model investigates the influence of all three exogenous variables on endogenous variables and the direct and indirect paths through which these variables regulate crop damage, measured as the number of damaged fruit. We include direct paths for measuring the influence of landscape complexity (Chaplin-Kramer et al. 2011) and local plant species (Letourneau et al. 2011) and flower richness on natural enemies (Balzan et al. 2014) since these were shown to influence enemy diversity. Moreover, given that it has been shown that landscape complexity affects vegetation diversity at the local scale (Carlesi et al. 2013; Gaba et al. 2010; Gabriel et al., 2005), we investigate the effect of the former on natural enemies and crop damage through an indirect effect. The availability of alternate prey has also been shown to increase the abundance of generalist predators in tomato crops within the Mediterranean region (Balzan and Moonen 2014, Torres and Boyd 1999). Diversity of sap-sucking bugs (abundance of member of the Order Hemiptera and species richness of Heteroptera bugs, of the families Rhopalidae, Miridae, Pentatomidae, Lygaeidae, Nabidae, Geocoridae, Anthocoridae, which accounted for 87.83% of Hemiptera recorded within this study) which accounted for most of the herbivores recorded from the field margins was included as a measure of alternative prey. Previous studies have demonstrated that increased natural enemy diversity at the field scale leads to a higher natural pest control (Rusch et al. 2013; Jonsson et al. 2012; Letourneau et al. 2012; Mitchell et al. 2014). Richness of predator and parasitoid groups was used to indicate natural enemy diversity. We decided to pool predator and parasitoid data together since our analyses indicate similar effects of local and landscape management on these functional groups and this reduced the number of paths in the model increased statistical power. The direct influence of field margin vegetation richness on crop damage is also investigated since increased plant diversity at the local scale has been shown to influence the pest directly, for example by providing food resources and shelter (Balzan and Wäckers, 2013; Winkler et al. 2009) or by disrupting the pests' ability to locate or access the host crop (Finch and Collier 2000). The path analysis also investigates the direct influence of landscape complexity on crop damage, since simpler landscapes tend to be more attractive to pests (Poveda et al. 2012; Grez et al. 2014), as suggested by the resource concentration hypothesis (Root 1973). Based on previous observations within the study area, the direct influence of time of harvest on Lepidoptera-caused damage is also included within the model (Balzan and Moonen 2012). The path analysis models described above were also carried out with Noctuidae and T. absoluta-caused crop injury. 3 (a) (b) 4 Supplementary data table S2 - Plant species composition of uncropped edges and the relative abundance in the surveyed fields. Species Relative Abundance (%) 1 Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. 13.116 2 Convolvolus arvensis L. 11.049 3 Picris echioides L. 5.556 4 Daucus carota L. 5.392 5 Portulaca oleracea L. 5.165 6 Equisetum palustre L. 4.235 7 Solanum nigrum L. 2.753 8 Phalaris paradoxa L. 2.592 9 Rubus fruticosus L. 2.395 10 Avena sterilis L. 2.155 11 Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop. 2.142 12 Echinocloa crus-galli (L.) Beauv 2.040 13 Pulicaria dysenterica (L.) Bernh. 2.030 14 Calystegia sepium (L.) R. Br. 2.027 15 Chenopodium album L. 1.876 16 Polygonum aviculare L. (s. l.) 1.817 17 Foeniculum vulgare Mill 1.748 18 Galium album Mill 1.594 19 Beta vulgaris L. s. l. 1.551 20 Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. 1.331 21 Medicago sativa L. 1.061 22 Elymus repens (L.) Gould. 1.061 23 Dactylis glomerata L. s. str. 0.959 24 Cuscuta sp. 0.894 25 Lolium rigidum Gaudich 0.871 26 Mentha suaveolens Ehrh 0.844 27 Symphyotrichum squamatum (Spreng.) G.L.Nesom 0.835 28 Amaranthus blitoides S. Watson 0.805 29 Cyperus glomeratus L. 0.789 5 Species Relative Abundance (%) 30 Coleostephus myconis (L.) Cass. 0.739 31 Setaria viridis (L.) P. Beauv. 0.733 32 Clematis vitalba L. 0.664 33 Dittrichia viscosa (L.) Greuter 0.651 34 Elaeoselinum asclepium (L.) Bertol. 0.647 35 Bromus sterilis L. 0.637 36 Phragmites australis (Cav.) Steud. 0.572 37 Rumex crispus L. 0.542 38 Xanthium italicum Moretti 0.513 39 Torilis arvensis (Huds.) Link 0.496 40 Eragrostis cilianensis (All.) Janch. 0.496 41 Festuca rubra L. 0.493 42 Agrostis gigantea Roth 0.493 43 Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronquist 0.476 44 Humulus lupulus L. 0.414 45 Taraxacum officinale Webb 0.391 46 Rosa sp. 0.378 47 Lolium multiflorum Lam. 0.378 48 Amaranthus blitum L. 0.368 49 Amaranthus albus L. 0.361 50 Ferula communis L. 0.358 51 Cyperus longus L. 0.358 52 Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. 0.315 53 Melissa officinalis L. 0.306 54 Picris angustifolia subsp. angustifolia DC 0.302 55 Crataegus monogyna Jacq. 0.296 56 Polygonum equisetiforme Sm 0.289 57 Apera spica venti (L.) P. Beauv. 0.289 58 Smilax aspera L. 0.243 59 Equisetum giganteum L. 0.243 60 Holcus lanatus L. 0.240 61 Stachys palustris L. 0.237 6 Species Relative Abundance (%) 62 Cornus sanguinea L. 0.230 63 Trifolium arvense L. 0.210 64 Persicaria maculosa Gray 0.204 65 Andryala integrifolia L. 0.204 66 Fallopia convolvolus (L.) Á.Löve 0.200 67 Phalaris minor Retz. 0.194 68 Verbena officinalis L. 0.181 69 Kickxia commutataFritsch 0.181 70 Atriplex patula L. 0.174 71 Equisetum hyemale L. 0.164 72 Sinapis arvensis L. 0.161 73 Malva silvestris L. 0.154 74 Bromus briziformis Fisch. & C.A.Mey. 0.148 75 Chrozophora tinctoria (L.) A.Juss. 0.141 76 Mentha sp. 0.138 77 Potentilla reptans L. 0.125 78 Plantago serraria L. 0.118 79 Typha angustifolia L. 0.112 80 Plantago lanceolata L. 0.112 81 Anagallis arvensis L. 0.105 82 Lathyrus sylvestris L. 0.102 83 Salvia sp. 0.099 84 Trifolium pratense L. 0.095 85 Briza maxima L. 0.095 86 Knautia arvensis (L.) Coult 0.092 87 Equisetum arvense L. 0.082 88 Epilobium tetragonum L. s. str. 0.082 89 Dipsacus fullonum L. 0.076 90 Amaranthus retroflexus L. 0.076 91 Equisetum telmateia Ehrh. 0.069 92 Atriplex prostrata subsp. calotheca (Rafn) M.A.Gust 0.069 7 Species Relative Abundance (%) 93 Silene gallica L. 0.066 94 Sonchus oleraceus L. 0.059 95 Populus sp. 0.059 96 Artemisia vulgaris L. 0.056 97 Gaudinia fragilis (L.) P. Beauv. 0.053 98 Galium verum L. 0.053 99 Lactuca serriola L. 0.049 100 Polycarpon tetraphyllum (L.) L. 0.043 101 Nigella damascena L. 0.039 102 Anthemis altissima L. 0.039 103 Potentilla alba L. 0.036 104 Kickxia spuria (L.) Dumort. 0.036 105 Bromus tectorum L. 0.036 106 Aristolochia rotunda L. 0.036 107 Anthemis arvensis L. 0.036 108 Lamium purpureum L. 0.033 109 Hypericum perforatum L. 0.033 110 Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers. 0.030 111 Raphanus raphanistrum L. 0.026 112 Anagallis arvensis subsp. Foemina (Mill.) Schinz & Thell 0.026 113 Veronica sp. 0.023 114 Hierarcium sp. 0.023 115 Ammi majus L. 0.023 116 Lathyrus annuus L. 0.020 117 Lapsana communis L. 0.020 118 Asparagus tenuifolius Lam. 0.020 119 Unidentified species 0.016 120 Tragopogon dubius Scop 0.016 121 Eragrostis cilianensis (All.) Janch 0.016 122 Sonchus asper (L.) Hill 0.013 123 Helianthus annuus L. 0.013 8 Species Relative Abundance (%) 124 Galium lucidum All. 0.013 125 Datura stramonium L. 0.013 126 Arctium lappa L. 0.013 127 Anchusa arvensis (L.) M. Bieb. s. l. 0.013 128 Vitis sp. 0.010 129 Rhamnus alaternus L. 0.010 130 Quercus sp. 0.010 131 Mentha longifolia(L.) L. 0.010 132 Mentha aquatica L. 0.010 133 Hordeum murinum L. s. l. 0.010 134 Cichorium intybus L. 0.010 135 Cerastium fontanum Baumg. s. str. 0.007 136 Centaurium pulchellum (Sw.) Druce 0.007 137 Agrostis stolonifera L. 0.007 138 Trifolium repens L. 0.003 139 Phalaris brachystachys Link 0.003 140 Paspalum dilatatum Poir 0.003 141 Bromus hordeaceus L. 0.003 142 Blackstonia perfoliata (L.) Huds. 0.003 9 Supplementary data table S3- Influence of Shannon vegetation diversity (H) and Shannon habitat-type diversity in landscape buffers of 1000m (H), harvest date (T), year (YR) and their interactions on yield loss (number of damaged fruits) and pest damage (number of fruit galleries). P-values were obtained from likelihood ratio tests in which deviances with and without the term in the models were compared. Variables in bold were included in the minimum adequate model (MAM, the symbol “*” in the MAM indicates that the model includes the shown variables and all the interactions between them). Independe nt variable (a) Crop damage df Vegetation Diversity (H) χ2 Habitat diversity (H) χ2 p-val (b) Noctuidae-caused fruit injury (c) T. absoluta-caused fruit injury Vegetation Diversity (H) Vegetation Diversity (H) Habitat diversity (H) Habitat diversity (H) p-val χ2 p-val χ2 p-val χ2 p-val χ2 p-val 0.31 1.34 0.25 H 1 1.43 0.23 17.20 <0.000 1 2.30 0.13 6.59 0.01 1.05 T 1 7.63 0.006 16.73 <0.000 1 8.58 0.003 13.73 0.000 2 19.41 YR 1 0.10 0.75 2.85 0.09 4.43 0.03 2.47 0.12 9.38 0.002 9.52 0.002 HxYR 1 8.75 0.003 0.00 1.00 3.18 0.07 1.03 0.31 1.71 0.19 1.91 0.17 TxYR 1 0.00 1.00 0.08 0.77 2.90 0.09 3.10 0.08 11.28 0.0008 HxT 1 2.67 0.10 0.64 0.42 2.82 0.09 0.18 0.67 4.15 0.04 3.84 0.05 HxYRxT 1 5.23 0.02 5.32 0.02 5.50 0.02 1.90 0.17 0.03 0.85 1.36 0.24 MAM H*YR*T H*YR*T H*YR*T H+T <0.0001 30.3 <0.000 6 1 H*T+T*YR 14.8 0.0001 2 H*T+T*YR 10 Supplementary Data Fig. S3– Path diagram for measuring the direct and indirect effects on (a) T. absoluta (df = 6, p-val 0.99, Satorra-Bentler correction = 0.90) and (b) Noctuidae-caused tomato crop injury (df = 6, p-val 0.99, Satorra-Bentler correction = 1.22) using abundance data. Solid lines denote significant and line width indicates strength of the relationship, while the values represent standardised path coefficients. Parameters in a grey box are exogenous variables whilst those in black boxes are endogenous variables. * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001. (a) (b) 11