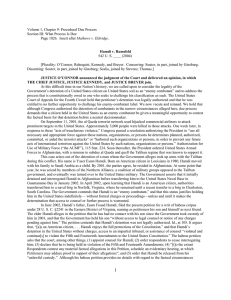

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2004)

Street Law Case Summary

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

Argued: April 28, 2004

Decided: June 28, 2004

Facts

The Government alleges that Yaser Esam Hamdi was captured in Afghanistan, AK-47 in hand, when his military unit surrendered in late 2001. The Government claims that he had trained with the Taliban and had ties to al Qaeda. After being held initially with other captives in Guantanamo

Bay, the military learned that he had been born in Louisiana, making him a United States citizen despite having grown up in the Middle East. He was first granted access to counsel on February 4,

2004, although he contends that the conditions of the meeting did not allow him to communicate with his lawyer confidentially.

On June 11, 2002, his father Esam Fouad Hamdi filed a habeas petition on his behalf in Federal

District Court in the Eastern District of Virginia.

1

He sought release on the ground that his son was a United States citizen who was being held without having charges brought against him or access to counsel in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.

The Court ordered immediate and confidential access to counsel, which the United States appealed.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals allowed for a limited review of evidence presented by the

Government to demonstrate that Hamdi was indeed an “enemy combatant” captured during hostilities in Afghanistan in lieu of ordinary proceedings. When the district court reconsidered the matter, it found that the Government had failed to meet its burden of proof in establishing Hamdi’s role as an enemy combatant if it were to hold him without charge. On appeal, the Fourth Circuit again reversed the district court’s ruling. This time it challenged the District Court’s application of its earlier decision, emphasizing the very limited nature of judicial scrutiny in cases where the executive alleges that the detained person is an enemy combatant. Hamdi appealed this ruling to the

Supreme Court.

Issues

Can the President indefinitely detain Yaser Esam Hamdi, an American citizen, who the President claims was captured in Afghanistan during a military confrontation and serving as an “enemy combatant”; OR do the Constitution and federal law compel the government to allow him access to counsel and an opportunity to challenge the factual basis for his detention?

What is the role of the courts in regulating such claims of executive power in specific cases?

1 Two earlier petitions were filed on Hamdi’s behalf, but both were dismissed for lack of standing, that is, the individual serving as his representative could not demonstrate an adequate connection to him.

© 2004 Street Law, Inc. 1

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

Constitutional Protection from Unjustified Deprivation of Liberty

Article I, Section 9, Clause 2:

“The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of

Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

Amendment V:

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger . . . nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law . . . .”

Amendment VI:

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of

Counsel for his defence [sic].”

Arguments for Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld (the United States)

The power to detain “enemy combatants” captured in war zones is clearly within the

Commander-in-Chief’s powers and is not affected by his status as a Citizen.

The grant of power by Congress strengthens, rather than limits the Executive’s power.

Hamdi’s detention is consistent with international treaty obligations and standard military practices.

The Executive’s interpretation of the record demonstrates that Hamdi is an enemy combatant and the courts should afford the utmost deference to that finding.

The limited scope of review for the courts does not violate the Constitution, which even in conjunction with other laws, requires no additional proceedings.

Arguments for Hamdi

United States citizens should not be subject to two years of detention unless they have access to meaningful review by habeas corpus proceedings in the courts, including access to counsel.

Allowing the executive to exercise such discretionary power over those it labels “enemy combatants” undermines the purpose of a congressional law prohibiting the unilateral indefinite detention of citizens.

The President’s Commander-in-Chief powers do not permit him to indefinitely detain citizens once taken beyond “areas of actual fighting,” which is also in violation of the laws of war (as defined by the Geneva Conventions).

© 2004 Street Law, Inc. 2

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

Congress is in exclusive possession of the power to authorize the detention of American citizens that is “more than temporary” and has not done so here.

Plurality

Justice O’Connor wrote the plurality opinion, joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices

Kennedy and Breyer. The opinion held that when Congress authorized the use of military force in response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, it gave the president the authority to label U.S. citizens

“enemy combatants” as well as detain them. However, Justice O’Connor made clear that such people need to “be given a meaningful opportunity to contest the factual basis for that detention before a neutral decisionmaker.” As outlined by the court however, the opportunity due in this situation is not the same process provided in criminal trials. After being given “notice of the factual basis for his classification, an alleged enemy combatant might have a hearing before a neutral military tribunal, where rules of evidence could be relaxed and the defendant would bear the burden of proving that he is not an enemy combatant.

Once someone is found by such a tribunal to be an enemy combatant, the opinion allows for imprisonment until the end of hostilities, in this case the end of active warfare in Afghanistan, rather than the more nebulous and uncertain “war on terror.” The opinion repeatedly stressed that the justification for such detention could not be to interrogate but must be to prevent the individual from participating in the war. Overall, the opinion made clear that the courts justifiably maintain a role in the process of balancing individual rights against executive war-making powers, because

“history and common sense teach us that an unchecked system of detention carries the potential to become a means for oppression and abuse of others who do not present that sort of threat.”

Concurrence

Justice Souter’s concurring opinion, which Justice Ginsberg joined, agreed with the plurality that the federal courts have the power to hear Hamdi’s appeal, but disagreed with the plurality’s holding that

Congress had authorized the President to detain citizen enemy combatants. Therefore, the opinion disputed the majority’s holding that simply providing Hamdi with a hearing before a military tribunal or a proceeding with a presumption of evidence in favor of the Government would be sufficient to satisfy due process.

Dissents

Justice Scalia’s dissent, joined by Justice Stevens, took issue with the plurality’s grant of power to the executive, absent a clear congressional suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. In response to the

Government’s pleas of special circumstances and necessity, the opinion noted “criminal [processes were historically] viewed as the primary means—and the only means absent congressional action suspending the writ—not only to punish traitors, but to incapacitate them.” Though the opinion is a severe rebuke to the Government’s position, it did concede that, “[when] the writ is suspended, the

Government is entirely free from judicial oversight,” and the Court has no power to review the legitimacy of the suspension itself. In closing, Justice Scalia pointedly reminds his readers, “[the] role of habeas corpus is to determine the legality of executive detention, not to supply the omitted process necessary to make it legal.”

© 2004 Street Law, Inc. 3

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

Justice Thomas’ dissent was the only opinion to accept the Government’s argument in full. He advocated extreme deference to the executive’s Commander-in-Chief powers, and would have adhered to what he characterized as the Court’s tradition of limited second-guessing of the executive in wartime. His opinion formed the fifth vote with the plurality to acknowledge the sole point that the President can label American Citizens “enemy combatants” and exempt them from certain liberties available to the rest of the civilian population. He grounded his holding in a general notion of a strong executive in our constitutional design, rather than Congressional authorization. He felt that the Court was inadequately deferential to the legitimate concerns of the executive in “the war context,” including the possibility that a hearing as envisioned by the plurality would expose highly classified information.

© 2004 Street Law, Inc. 4