CONSULTATION DRAFT 3 Antenatal care for women with mental

advertisement

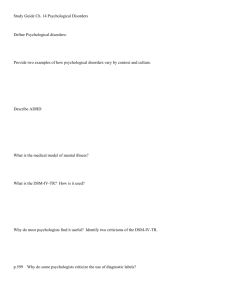

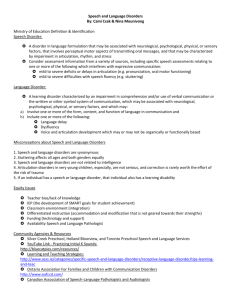

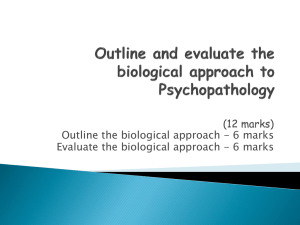

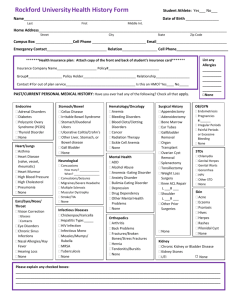

CONSULTATION DRAFT 3 Antenatal care for women with mental health disorders1 Mental health disorders have been identified as a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the UK (Lewis 2007) and as one of the top three causes of indirect maternal mortality in Australia (Austin et al 2007). There is increasing evidence that untreated maternal depression (Davalos et al 2012), stress and anxiety (Zelkowitz & Papageorgiou 2012) also adversely affect the developing fetus, with implications extending into childhood. Use of antidepressants in pregnancy has also been associated with adverse effects in the fetus and newborn, but they are believed to be relatively safe (Udechuku et al 2010). Assessment of the risks and benefits for the individual woman is appropriate when use of antidepressants is being considered (see Section Error! Reference source not found.). Australian research indicates a high prevalence of depression and anxiety during pregnancy, with up to one in ten (9%) women experiencing depression (Buist & Bilszta 2006) and anxiety disorders likely to be as, or more, common (beyondblue 2011). Refugee women with a history of torture or trauma are at increased risk of mental health disorders, including anxiety and depression (Costa 2007). While specific data on low prevalence mental health disorders (eg schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe personality disorders) in pregnant women in Australia are not available, recent studies suggest that schizophrenia is present in 1% of the population world wide, lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder in Australia is estimated as 1.2% (University NSW 2002) and personality disorders are present in 6.5% of Australian adults, with borderline personality disorder in approximately 1% (Jackson & Burgess 2000). To match the needs, preferences and expectations of women with mental health disorders, maternity services need to work within collaborative and consultative frameworks. This includes clearly defining roles and responsibilities for everyone involved in a woman’s care and working within established clinical networks and systems to facilitate timely referral and transfer to relevant services when appropriate. Continuity of care and carer also contribute to improved experiences for women. 3.1 Identifying and managing mental health disorders during pregnancy “Depression and related disorders affect the wellbeing of the woman, her baby and her significant other(s) (eg partner), and have an impact on relationships within the family, during a time that is critical to the future health and wellbeing of children.” (beyondblue 2011) Early identification and management of mental health disorders can minimise their detrimental effects during pregnancy and early parenthood. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy are assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)2 and clinical judgement, as outlined in Part B of Module I of the Guidelines. Bipolar disorder is characterised by episodes of hypomania or mania and depression (APA 2000). Women who have already experienced bipolar disorder have a significant risk of relapse in the early postnatal period. Relapse may also occur during pregnancy, especially if a woman ceases medication when planning to become pregnant or on confirmation of pregnancy. 1 This section is a revised version of material included in Module I of the Guidelines. 2 While the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was developed for use postnatally, antenatal evaluation is generally associated with an adequate sensitivity and specificity to detect depressive symptoms antenatally. There is also evidence to support its use in detecting symptoms of anxiety. CONSULTATION DRAFT Puerperal psychosis is a relatively rare but severe psychotic illness with risks of potential serious self or infant harm. While puerperal psychosis is rare in the general population (1–2 women per 1,000 live births), women who have had bipolar disorder or a previous episode of puerperal psychosis have a one in two chance of puerperal psychosis recurring in the early postpartum period. Preventive medication from immediately after the birth is usually indicated (Bergink et al 2012). Psychiatric referral antenatally is essential. Borderline personality disorder typically emerges in adolescence or young adulthood (Chanen et al 2007) and has a higher prevalence (Moran et al 2006) and number of symptoms (Cohen et al 2005) at this time (eg in childbearing years). It is characterised by a pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image and affects, and marked impulsivity (APA 2000) and is associated with severe impairment of psychosocial function and a high risk of selfharm or suicide (Leichsenring et al 2011). Recognising borderline personality disorder allows health professionals to better tailor treatment goals and expectations, manage personal reactions, set effective boundaries and avoid potential confrontations (Ricke et al 2012). Schizophrenia is characterised by delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech, grossly disorganised or catatonic behavior and negative symptoms (ie low levels of emotion, loss of motivation), with one or more major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations or self-care markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset (APA 2000). It is appropriate for health professionals in primary care to have an understanding of the basic issues facing women with mental health disorders. Clinical practice guidelines developed for the general population may be useful (see Section Error! Reference source not found.). Overall, collaboration with the woman and her family and providing compassionate and nonjudgemental care are the cornerstones of management. For more severe mental health issues, such as schizophrenia and drug-related psychoses, working collaboratively with trained mental health professionals is recommended where possible. When risk of suicide is identified (eg through question 10 of the EPDS; see Section 7.6, Module I) immediate referral to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional is required. Sources of information about mental health disorders in perinatal practice and mental health referral and advice are included in Section Error! Reference source not found.. Table 3.1: Components of care for minimising the detrimental effects of mental health disorders Women are assessed during pregnancy for symptoms of high prevalence mental health disorders (depression and anxiety) and asked about their personal and family history of mental health disorders Women with symptoms of a mental health disorder are linked with appropriate services Women are given appropriate information about the purpose, process and voluntary nature of proposed clinical assessments and screening tests Care for women who have experienced, received treatment for, or are currently experiencing low prevalence mental health disorders, is provided in collaboration with relevant mental health professionals, with continuing care provided by a health professional with whom the woman has established trust Current psychotropic medicine use is discussed and women receive appropriate information on the risks/benefits of treatment, timing of onset of effect and risk of relapse if medicines are discontinued Preventive treatment is considered for women at risk of bipolar disorder or puerperal psychosis When risk of suicide is identified, immediate safety is assessed and referral made to a psychiatrist or other mental health professional