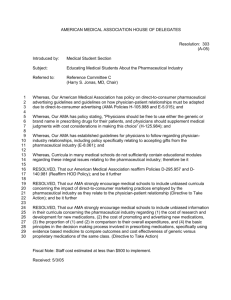

A Proposal for Pharmaceutical Industry

advertisement

Michelle Mills Professor Brookman November 20, 2014 Proposal for Physician-Industry Relationship Reform When I was fifteen I was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder. I was a week away from beginning an intense regiment of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers when I discovered my psychiatrist had strong affiliations with the makers of Lithobid, Depakote, and Seroquel. I remember him telling me that the youngest person he had diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder had been five years old. Unfortunately, in the modern world of health care, this story is not uncommon. The medical industry’s use of physicians as a tool in pushing their products is an overwhelmingly large part of their marketing system. In 2002, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) companies spent around $22 billion marketing to physicians, compared to a mere $3.3 billion marketing directly to consumers. (1079) This is why it is vital that a plan is enacted which strengthens and fosters a healthy relationship between the physicians and industry, in which all parties, including the patients/consumers, benefit. Brennan et al proposes that “More stringent regulation is necessary, including the elimination or modification of common practices related to small gifts, pharmaceutical samples, continuing medical education, funds for physician travel, speakers’ bureaus, ghostwriting, and consulting and research contracts.” (429) By banning unethical marketing strategies, physicians will be free of industry manipulation and the two bodies can independently succeed, alongside each other. 1 Most physician-industry interaction takes place on the small scale, but do not be deceived; these day-to-day communications are much more lucrative and far-reaching than you might think. Annually, the pharmaceutical industry invests over $4 billion dollars in a marketing technique called detailing, which is based solely on the industry’s relationship with physicians. (265) Detailing is the practice in which pharmaceutical sales representatives visit medical practitioners. Part of the representative’s job is to brief the physician on new medications: their intended use, dosage, advantages and disadvantages. However, the medical industry is a business, and so the detailers’ main priority is to sell their product. The ideal representative is attractive, charming, and knows everything about the medical staff they interact with from their childhood nickname to their opinions on waterskiing. Former representative, James Reidy had a first-hand perspective. “An official job description for a pharmaceutical sales rep would read: Provide health-care professionals with product information, answer their questions on the use of products, and deliver product samples. An unofficial, and more accurate, description would have been: Change the prescribing habits of physicians.” (3) Detailers consistently visit offices bringing meals and gifts on behalf of the pharmaceutical company. Most of the gifts are small mugs, highlighters, and notepads with the company name printed on them. These are referred to as “reminder items,” which increase medical staff exposure to the brand, and consequently boost the likelihood of the brand being prescribed in that office. (268) On a larger scale, many physicians receive payment to attend conferences, meetings, and seminars, where their travel and lodging costs are taken care of. Other incentives provided by the industry include grants for research projects, ghostwriting services, and of course, the customary gifting of pharmaceutical samples. (430) Prescription samples are a favorite of the industry, given to physicians so that they can, in return, provide the drugs to their patients at no cost. In these two exchanges, it seems 2 as if everyone wins. The patient gets an expensive medication for free, and the doctor has done his job. However, the real victor in this situation is naturally the industry. Proponents of gift giving claim it has little-to-no impact on physicians, but research consistently shows that even the most seemingly innocent gifts, when accepted, trigger the receiver’s innate desire to reciprocate the act of giving. (267) Studies and research have shown that even the most unbiased, ethical physician is likely to fall victim to this marketing technique which plays upon human nature. (1078) One such analysis was conducted with the goal of measuring the pharmaceutical industry’s impact on the knowledge, attitudes and behavior of physicians. Using twenty-nine case studies and the knowledge of five key informants, the study found that interaction with the medical industry negatively affected physicians in all three areas. Perhaps most alarming was the effect on behavior - “making formulary requests for medications that rarely held important advantages over existing ones; nonrational prescribing behavior; increasing prescription rate; prescribing fewer generic but more expensive, newer medications at no demonstrated advantage.” (378) Employing the Utilitarian Approach, I argue with Brennan et al that gift giving between the medical industry and physicians be completely prohibited due to the countless negative impacts that this particular give-and-take partnership presents. The exchange of gifts will include but not be limited to: free meals, payment for time for travel to or at meetings, and payment for participation in online Continuing Medical Education.” (431) Other failed gift-giving policies, have been more lenient, banning certain gifts but allowing others. Even the PhRMA Code allows for “items not of substantial value ($100 or less) and do not have value to healthcare professionals outside of his or her professional responsibilities.” (275) Speaking on this before the Senate, Shahram Ahari said “In the past, as a sales rep, I would spend $100 on a golf club for 3 a physician allowing him/her to spend $100 on a medical textbook. Today, I buy the book and he/she buys the golf club. It is still a gift, still a perk, and still $100.” (275) Brennan et al’s proposal does not make exceptions, taking into account the fact that even the smallest gifts can hold heavy influence. For this reason, the proposal has a high chance for success. Without free meals, payment for attending seminars, and even those goofy-looking slinky pens, there will be a drastic decrease in unjustifiable preference presented by physicians regarding pharmaceutical choices. Fewer patients will be wrongly diagnosed, and given a prescription that they do not need or could possibly harm them. There will be an increase in the number of affordable, generic drugs being prescribed and consequently, health insurance costs will decrease. Physicians will no longer be inclined to spend their time listening to the spiel of pharmaceutical sales representatives, liberating them from a barrage of inaccurate, biased information. Included in the prohibition of gift giving, will be the distribution of free pharmaceutical samples to physicians. Not only does sampling influence doctor’s prescribing behaviors, but it also raises the price of the drug for those who pay for it, as the production cost for these samples is approximately two to three billion dollars annually. (1080) It is also important to know that drug samples do not always make it into the hands they are intended for. In one study, almost half of physicians admitted to claiming samples for themselves, their friends and family. (1) More worryingly are the results of a nationally representative survey that included a sample of individuals who have received at least one prescription drug in the last year. This Americanbased study found that people in the highest income bracket are most likely to have received pharmaceutical samples. Not only that, but people with continuous health insurance are more likely to receive samples than the uninsured. (1) In summary, the people buying prescription drugs are paying extra so that samples of that drug can go into the pockets of the America’s most 4 wealthy. While it is true that drug sampling can be beneficial in ways such as strengthening physician-patient relationships or quickly setting a medication routine in motion, the practice has an abundance of defects, which justify it being abolished. Without drug sampling, physicians will not feel impelled to choose convenience of a drug over efficacy and the risks vs. benefits. Similarly, patients will no longer buy a certain brand of pharmaceutical, just because their doctor gave them a free dosage of it. Based on the evidence, we can confidently say that the industry’s goal of sampling is not to spread the availability of the most effective medications and benefit low-income patients. In the interest of altruism, there are possible approaches to remedy this. As an alternative to drug sampling, Brennan et al proposes a system of vouchers for low-income patients, which effectively distances the industry from the physician, while successfully accommodating those in need. (431) This approach ensures that assistance in buying pharmaceuticals is not wasted on the financially dependent or the personal use of medical staff. The overall result of this policy reform will be a return to elegant-evidence based medicine, elegant medicine meaning “providing patients with the best result that has the lowest cost, the least discomfort, and the fewest and least-risky interventions” and evidence-based as “integration of the best available clinically relevant research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” (1079) By implementing the policy of Brennan et al, physicians will benefit on a moral level, having their professional integrity preserved and ethical responsibility filled. They will know that they are giving their patients the care they deserve, unaffected by marketing strategy. Things like costly medicine, false diagnoses and unnecessary prescriptions will no longer harm patients. As for the medical industry, it will find a new outlet for product promotion, and will continue to thrive for as long as people need medicine. 5