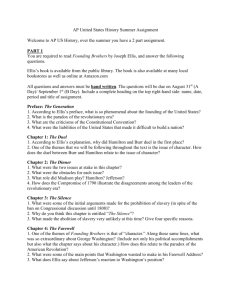

Founding Brothers Thesis

advertisement

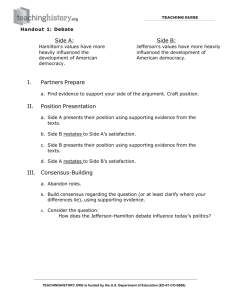

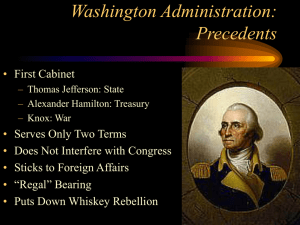

Founding Brothers: Revisiting and Re-reading the Introduction, The Generation Constructing a Thesis (by working backwards through the chapter to come full circle) How did the Did they succeed? Founding Fathers succeed? But, what is the debate over Who took on the “true meaning” of the Revolution all this contradiction? How bad did things look? what But did they succeed at accomplishing? about? The argument became part of our political institutions and Constitution. Pretty Is that it? Is it just a Hamilton vs. Jefferson argument? simple- is that it? pp 16-18 How did the Founding Fathers succeed? At the bottom of page 16, Ellis raises the question, in so many words, “how did the Founding Fathers succeed?” What factors contributed to their success? He then states 4 factors on pages 17-18. Name them. 1. Checks and balances of diverse personalities and ideologies 2. Face Time: Personal knowledge of each other through frequent correspondence, face to face 3. No slavery; slavery taken off the table for political debate 4. A keen sense of their own historical significance (even though they didn’t know the history they were making) p. 15 But what did they succeed at accomplishing? 1. They built debate about the “true meaning” of the Revolution into the fabric of our national identity. 2. They managed to “contain the explosive energies of the debate in the form of an ongoing argument or dialogue that was eventually institutionalized and rendered safe by the creation of political parties. pp 13-15 But, what is the debate over the “true meaning” of the Revolution all about? 1. The Jeffersonian “spirit of ‘76” is all about personal liberty; personal liberty is the core revolutionary principle and Hamilton is enemy number 1. This approach “regards any accommodation of personal freedom to governmental discipline as dangerous. “ 2. The Washington “spirit of ‘76” is all about the nation first; it’s about “surrendering personal, state, or sectional interests to the larger purposes of American nationhood.” It means 1787 is more important than 1776. And this means that Jefferson is enemy number 1, and Hamilton is the visionary. Note: The Friendship revisits “what the American Revolution meant” (p.223). The Friendship focuses on an exchange of 158 letters between Adams and Jefferson in which Ellis cites excerpts from their letters that clearly indicate that their friendship and admiration for one another as co-revolutionaries is fully restored, but that the way to read their letters is as an argument by Adams with “the philosopher-king” that the Jeffersonian version of history- “destined to dominate the history books”- was wrong and needed to be corrected in “letters to posterity” (pp 223-227). pp 12-13 Is that it? Is it just a Hamilton vs. Jefferson argument? 1. No, it’s a Washington, Adams, Adams, Hamilton v. Jefferson, Madison, and Burr with Franklin speaking out loudly against slavery. It’s a debate involving “the greatest generation of political talent in American history.” … the relatively small number of atypical white “Americans” who wielded political power from the Revolution through the early Republic. 2. Sort of. Focusing on “Hamilton v Jefferson” is a good way to think about the coercive power of government created in 1787 v the “pursuit of happiness” principles of 1776. 3. YES! The Hamilton v Jefferson argument was fought among the “relatively small number of leaders, who knew each other, who collaborated and collide with one another” took their personality and ideology differences and made them into “the principles of checks and balances imbedded structurally in the Constitution. “ pp 10-13 OK, I get it. The United States was founded on a “Hamilton v Jefferson argument” about government power and personal liberty, and the argument became part of our political institutions and Constitution. Pretty simple- is that it? 1. No, not at all. It wasn’t neat and pretty. 2. The most important events were all political; “The central events of the revolutionary era and the early republic were political.” And no one knew the history they were making in these debates, so it was high-stakes debates. 3. Plus, there were four major “liabilities:” a. Scale of the US b. Hatred / fear of concentrated political power c. No common history as a united people d. 700,000 slaves pp 3-10 How bad did things look? 1. Bleak and overwhelming. 2. “The very arguments used to justify secession from the British Empire also undermined the legitimacy of any national government capable of overseeing such a far-flung population, or establishing uniform laws that knotted together thirteen sovereign states and three or four distinct geographic and economic regions.” 3. “The national government established during the war under the Articles of Confederation accurately embodied the cardinal conviction of revolutionary-era republicanism: namely, that no central authority empowered to coerce or discipline the citizenry was permissible… it duplicated the monarchical principles the Am Rev had been fought to escape.” Who took on this contradiction? 1. Those “present at the creation” who knew they were making history, but not the history they were making. 2. A “tiny minority of prominent political leaders from several key states conspired to draft and then ratify a document designed to accommodate republican principles to a national scale. Did they succeed? 1. Yes, but it certainly wasn’t a given. 2. In 1789, “when the newly elected members of the federal government gathered in NY City” they were testing the proposition, “as Abraham Lincoln so famously put it at Gettysburg, ‘whether any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.’”