Comment Bank (Bronte PCs . . . October 2015)

advertisement

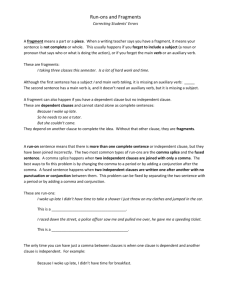

Comment Bank (Grammar Concerns from Jane Eyre PC) 1. PUNCTUATION OF TITLES: Generally speaking, we must use italics for long works and quotation marks for short ones. The notable exception here is a short poem published independently—not within a larger collection. Title (in italics): novels, textbooks, newspapers, magazines, journals, plays with more than a single act, book-length poems, poetry collections, short-story collections, films, television shows, musical albums, and works of art. Examples: Novels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary Textbooks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Elements of Literature Newspapers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Richmond Times Dispatch Magazines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Popular Mechanics Journals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Journal of Abnormal Psychology Full-Length Plays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie Poetry Collections . . . . . . . . . . . . . T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock and Other Observations Short-Story Collections . . . . . . . . . Katherine Mansfield’s The Garden Party and Other Short Stories Films . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity Television Shows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Big Bang Theory Musical Albums . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Diana Krall’s Wallflower Works of Art . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa Title (within quotation marks): chapters, articles, one-act plays, short poems (not published independently), short stories, episodes of a television show, and songs. Examples: Chapters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “American Masters: Whitman and Dickinson” (in Elements of Literature) Newspaper Article . . . . . . . . . . . . . “Dewey Defeats Truman” (famous gaffe by the Chicago Daily Tribune) Magazine Article . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “Marilyn Monroe: The Talk of Hollywood” (from Life 1952) Journal Article . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “The Anthropology of Corruption” (from Journal of Management Inquiry 2015) One-Act Plays . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Neil Simon’s “Fools” Short Poems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Cross of Snow” Short-Stories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” Television-Show Episodes . . . . . . . .“Lucy is Enceinte” (from I Love Lucy) Songs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” 2. USE OF THE LITERARY PRESENT: When a writer discusses a fictional plot, he/she must use the present tense. This makes perfect sense, since the action is suspended in time. For instance, when your children and grandchildren read The Count of Monte Cristo, Edmund will once again be unjustly imprisoned. He’ll once again exact revenge on his enemies. And Valentine will once again survive a poisoning. Never is any of this action really finished. Similarly, a literary critic should discuss the decisions that an author makes in the present, since those decisions will impact the narrative with every reading. So Flaubert characterizes Emma through her actions. He builds a correlation between bad novels and bad behavior. The difference, though, comes when the writer discusses the life of the writer. Flaubert was born once; he died once; his love affair with Louise Collet ended; and he was acquitted of criminal charges of indecency for writing the novel. Consequently, the student’s choice of tense depends upon the focus: literature in the present and history in the past. 3. ACTIVE vs. PASSIVE VOICE: The active voice makes the subject of the sentence the party that performs the “activity” of the verb, whereas the passive forces the subject into the position of object. Consider: My mother drove me to school this morning. (The subject acts.) I was driven to school this morning by my mother. (The subject is acted upon.) Please always prefer the active voice over the passive. The reason is simple; active verbs sound more decisive and authoritative—precisely the sort of tone we want you to cultivate in your writing. The passive, by contrast, makes the writer sound sheepish and uncertain. Consider these examples: ACTIVE (forceful) The author builds suspense by following two lines of action at once, making a conflict between the characters inevitable. Having published the novel in 1857, Flaubert faced charged of public indecency the following year. The juniors read Flaubert every year. PASSIVE (hedging) Two lines of action were given, so the characters were forced into conflict. The novel was published in 1857, and Flaubert was brought to court the following year on charges of public indecency. The novel is read by the juniors every year. 4. RUN-ON SENTENCES: The term run-on sentence is perhaps the most frequently misunderstood grammar term. Students generally think of this sort of sentence as one that simply is long and meandering. Not so! The term has a much more specific definition than that, and that definition has nothing to do with length. A run-on sentence is one that either lacks proper end punctuation entirely or makes improper use of the comma between two independent clauses. Let’s take a look at each kind of run-on: (Type 1: Fused Sentence) FUSED CORRECTED (with a period) CORRECTED (with a semi-colon) Raskolnikov has an inferiority complex he resents any man who can support and care for his family. Raskolnikov has an inferiority complex. He resents any man who can support and care for his family. (A period between independent clauses fixes the problem.) We went to Busch Gardens I rode in the cable cars. We went to Busch Gardens. I rode in the cable cars. Raskolnikov has an inferiority complex; he resents any man who can support and care for his family. (A semi-colon between independent clauses fixes the problem, as long as the second clause seems to complete the thought posed in the first one.) We went to Busch Gardens; I rode in the cable cars. (Type 2: Comma Splice) COMMA SPLICE 5. CORRECTED (with a conjunction) CORRECTED (with a semi-colon) Raskolnikov has an inferiority complex, he resents any man who can support and care for his family. Raskolnikov has an inferiority complex, so he resents any man who can support and care for his family. (The comma can remain between independent clauses, as long as an appropriately chosen conjunction follows it.) We went to Busch Gardens, I rode in the cable cars. We went to Busch Gardens, and I rode in the cable cars. Raskolnikov has an inferiority complex; he resents any man who can support and care for his family. (A semi-colon between independent clauses fixes the problem, as long as the second clause seems to complete the thought posed in the first one.) We went to Busch Gardens; I rode in the cable cars. COMMA PLACEMENT (between independent clauses joined by conjunctions): It is sometimes difficult for students to understand when to use a comma between independent clauses joined by a conjunction and when to skip it. Generally, you’ll want to include the comma. However, when one or both of the clauses are especially brief, we are not obligated to include it. Consider: Flaubert characterizes by means of individual actions, but Dostoevsky delves much more deeply into the character’s inner thoughts. Flaubert “shows” and Dostoevsky “tells.” My brother loves to tinker with worn-out motors, but he finds it torturous to do his homework. My brother loves cars but he hates homework. 6. COMMA PLACEMENT (with a compound predicate): Although it may seem that we need to place a comma between compound predicates (verbs), especially when the sentence seems a bit long and involved; however, this is not the case. Unless the second verb has a separate subject, we are dealing with only one independent clause that happens to include a conjunction. Consider: COMPOUND PREDICATE Flaubert employs the place setting to give context to the characters’ actions yet allows those characters to be human enough to act independently of that context. (Both verbs have the same subject, so no comma should appear in front of the conjunction.) The dance had students from all four of our high schools and afforded everyone an opportunity to get to make new friends. 7. INDEPENDENT CLAUSES JOINED BY A CONJUNCTION Flaubert employs the place setting to give context to the characters’ actions, yet he allows those characters to be human enough to act independently of that context. (Each of these verbs has a different subject, so a comma should appear in front of the conjunction.) The dance had students from all four of our high schools, and it afforded everyone an opportunity to get to make new friends. COMMA PLACEMENT (after introductory phrases and clauses): Just as sentence length determines whether we place a comma between independent clauses joined by a conjunction, it also determines whether we use one after introductory phrases and clauses. If the introductory element has fewer than four words, we don’t need a comma. If it has four words or more, the comma is “restrictive,” or required. Consider: Sentence with Introductory Phrase or Clause Bringing an unprecedented element of accurate detail to prose narrative, Flaubert does not shy away from startling or disturbing situations, as his literary forebears often do. Shaking with fear Molly listened to the key rattling in the door lock. Because Dostoevsky employs such a surrealistic atmosphere, critics often speculate that Raskolnikov’s experience is really just a fevered dream. Because he won Barry could choose from three door prizes. To force his enemies to suffer for betraying him, Edmund Dantes dons a variety of disguises and carefully manipulates each situation. To exact revenge Edmund Dantes dons a variety of disguises and carefully manipulates each situation. Explanation This introductory participial phrase has ten words, so we must follow it with a comma. This introductory participial phrase has only three words, so we don’t have to follow it with a comma. This introductory adverbial clause has seven words, so we must follow it with a comma. This introductory adverbial clause has only three words, so we don’t have to follow it with a comma. This introductory infinitive phrase has nine words, so we must follow it with a comma. This introductory infinitive phrase has only three words, so we don’t have to follow it with a comma. 8. SUBJECT-VERB AGREEMENT (when the subject is an indefinite pronoun): An indefinite pronoun is one that fails to establish the specific identity of the person, place, or thing to which it refers. Most often this is the result of the speaker’s desire to apply the statement generally, rather than specifically. Consider these examples: Both are valid options. Each of them hoped to score the winning goal. I made a nametag for only one of them. Anybody can get a good grade on a binder check. The teacher loves all of us. No one knows how to diagram a two-page sentence. Neither had the right answer. Rule 1: When a singular pronoun serves as the subject of a sentence, the writer must use a singular verb, no matter what words appear between them. Please remember that you will never find the subject of a sentence inside a prepositional phrase. The following indefinite pronouns are singular: another, anybody, anyone, anything, each, either, enough, everybody, everyone, everything, little, much, neither, nobody, no one, nothing, one, other, somebody, someone, and something. Examples: Everyone in both groups has a theater ticket. (Even though groups is plural, the subject is singular. The verb, therefore must be singular.) Each of my parents is a college graduate. (The subject is each and, therefore, requires a singular verb.) Rule 2: When a plural pronoun serves as the subject of a sentence, the writer must use a plural verb, no matter what words appear between them. The following indefinite pronouns are plural: both, few, many, others. Examples: Few have the nerve to argue with Mr. Meanteacher. Few in the class have the nerve to argue with Mr. Meanteacher. Many who hope for fame and fortune actually achieve it, and many do not. Rule 3: When one of the following indefinite pronouns serves as the subject of a sentence, the choice of singular or plural verb depends upon the object of the prepositional phrase that follows it: some, all, most, any, and none. Examples: Some of the pie remains in the cupboard. Some of the pies remain in the cupboard. All of the money is between the sofa cushions. All of the coins are between the sofa cushions. Most of the book is difficult to understand. Most of the books are difficult to understand. Any of my patience that survives that long essay exam is evidence of sheer willpower. Any of the pencils make dark marks on white notebook paper. None of the textbook explains our lab results. None of the textbooks explain our lab results. 9. COMMON BLOOPERS: Affect / Effect (see comment bank for Dumas paper) Use affect as a verb meaning “to cause results.” Have you ever wondered how habitual reading can affect one’s writing skills? The number of credits you’re taking in one semester will affect your grades. Use effect as a noun meaning “result.” Have you ever wondered about the effects of habitual reading? The effects of taking too many credits in one semester can be detrimental. Fewer / Less Use fewer as an adjective modifying (describing) a plural noun. I have fewer quarters in my pockets than nickels. Molly has fewer sisters than Dominique. Use less as an adjective modifying (describing) a collective quantity. I have less money in my pocket than Molly does. Molly has less family than Dominique. Amount / Number Use amount as a noun referring to a collective quantity. Use number as a noun referring to a plural. Bring / Take Use bring as a verb suggesting the transmission of an object from a remote spot to the location where the speaker presently is. Please bring your books to the meeting next week. You must bring your papers to class if you want me to grade them. Use take as a verb suggesting the transmission of an object from a remote spot to the location where the speaker presently is. Please take this application to the post office. If you take your papers home with you, how am I supposed to grade them? Loose / Lose Use loose as an adjective meaning “not stable.” It’s certain that you’re going to lose that loose tooth. Use lose as a verb meaning “to part with/from.” It’s certain that you’re going to lose that loose tooth. Alot / A Lot The only acceptable use of this word is the latter. Each of you has a lot of options when it comes to colleges and scholarships. Alright / All Right The only acceptable use of this word is the latter. Don’t worry. Everything will be all right.