Prefaces Paper

advertisement

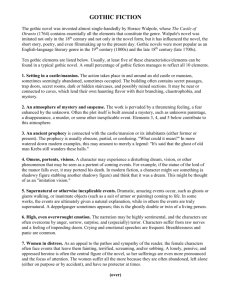

The Significance and Meanings Behind of the Prefaces in The Castle of Otranto Horace Walpole wrote the novel The Castle of Otranto in 1764, this was the first of the gothic novels. As the first to establish the modern gothic genre, Walpole had free reign over how to write and style his novel. The Castle of Otranto defied contemporary expectations by creating a new genre that the literary world had been craving. This was due in part to the prefaces that accompanied the first and second editions of Walpole’s novel. The first preface, which was printed with the first edition, provides the novel with an aura of mystery, presenting the novel as an ancient account of real events that was discovered and subsequently published. In this first preface, Walpole as subverts his authorship, deny any association to the work thorough the creation of a pseudonym. The second preface, which was printed with the second edition, refutes the first preface, with Walpole claiming The Castle of Otranto as his own, since the novel had proved to be successful, and declaring he only lied to protect the novel. A preface is the first original work a read encounters when opening a novel, it sets the tone for the book. It calls the readers attention to the author’s purpose in writing the work and provides the work with importance. Prefaces are indelibly important, there are “centuries of ‘hidden life,’ buried in the first of last pages of text” (263 Genette). There are any different types of prefaces, including traditional authorial, fictional, and later prefaces to name a few. The traditional authorial prefaces primary intention is to “ensure that the text is read properly” (197). An author places a high value on the treatment of their work when they write a preface, even if the preface is not a traditional authorial one. Walpole is doing this through both of his prefaces, but since he chose to write a fictional preface for the first edition of The Castle of Otranto and a later preface for the second edition, it is not clear what his intentions were. The fictional preface, which preceded the first edition of The Castle of Otranto, has confused many literary scholars and several theories to explain it have been developed. In 1765 when the novel was published, Walpole attributed it to “William Marshal, Gent” as a translation. The preface introduces the text as a manuscript that was “found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England. It was printed in Naples, in the black letter, in the year 1529” (3 Walpole). Using a pseudonym and explaining any inaccuracies or faults as the translator’s shortcomings effectively disassociate from his novel and from any problems a reader may encounter within it Walpole. This is technique that Walpole uses to conceal his authorship is similar to that used by Samuel Croxall when he published The Secret History of Pythagoras (Jung 33). Croxall concealed his authorship because he was attempting to bring about change and cause controversy in society. He achieved this by attacking notions of religion. By using a similar method to conceal his own authorship, Walpole is also trying to avoid any backlash he may have encountered by publishing The Castle of Otranto. The novel argues for a return to gothic superstitions, an argument that did evoke controversy, but Walpole was able to avoid much of this because of his preface (34). He guards himself from rejection and criticism by constructing the artificial (11 MacAndrew). Another theory for why Walpole chose to write a fictional preface for the first edition of his novel is linked to the gothic tradition. Walpole, which is why some of them are, reflected in his first preface, in part invented gothic tropes primarily elements of mystery. In The Castle of Otranto Walpole’s major accomplishment is “the creation of a mood” (62 Brown). This mood of mystery begins in the preface for the first edition, since the fictional preface is built on the backbone that the novel is ancient manuscript recently rediscovered, translated, and released to the public. However, this mood of mystery truly comes into play at the end of preface when Walpole detains his readers for a final remark. He states that although parts of the novel are “imaginary” he “cannot but believe that the groundwork of the story is founded in truth” (Walpole 8). This, on top of the earlier remarks about the novel being an ancient, exotic manuscript, allows the reader to surmise that a “mysterious world is about to be revealed” (11 MacAndrew). Walpole may have written the preface for the first edition of The Castle of Otranto in order to remove himself from his novel and disavow his authorship or perhaps he wrote it to establish the element of mystery, prevalent through out the work, early on in the novel. His purpose could have also been a combination of the two. Historically, fictional prefaces are written to disavow the author, the text, even the preface its self (278 Genette). But Walpole no longer desired to be removed from The Castle of Otranto once it started being successful. This is why he wrote a later preface for the second edition of the novel. The preface for the second edition of The Castle of Otranto is cut and dry in relation to the preface for the first edition. Traditionally, later prefaces are written by authors to address and inform new readers of their work (239 Genette). As previously mentioned, the novel started to become successful and Walpole wised to claim authorship. In order to do this, he released a second edition with his name proudly accompanying it alongside a new preface. This preface is used by Walpole to introduce and explain some of the gothic tropes and themes that can be found through out The Castle of Otranto. He claims that the novel was guided by nature and natural laws in order to create something sublime and beautiful (10 Walpole). The sublime and the beautiful can be seen through out the gothic tradition; one novel particularly prevalent with sublime and beautiful facets is Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein. Walpole finishes this second preface by attempting to explain why he wrote his first preface. As suggested by scholars, it seems that Walpole was trying to protect his name and dignity by originally removing himself from The Castle of Otranto. He see’s his fictional preface as excusable since he “created a new species of romance” and was “at liberty to lay down what rules I thought fit for the conduct of it”. However he can now be associated with his novel now that “the public has honored it sufficiently” (11 Walpole). Walpole wrote two separate prefaces for the first and second editions of The Castle of Otranto to suit his own purposes. He was introducing a new form of literature to society and at first he feared their reaction, thinking that it might tarnish his name. This is why he constructed fictional preface for the first edition of his novel. In it he passes off authorship to fictional figure and pronounces the work to be a translation of an ancient and mysterious text. This created an aura of mystery, which transcended the rest of the novel, and this perhaps increased public interest in Walpole’s work. When the novel became successful, Walpole published a second edition that included his name and a new preface. This later preface was done in the tradition that “it is never too late to inform a new public” (239 Genette). In it, Walpole writes his genius, effectively claiming The Castle of Otranto as his own. Both prefaces present a way for the readers to interpret the texts, but Walpole’s primary intention behind each of them was personal pride. Works Cited Brown, Marshall. The Gothic text. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2005. Print. Genette, Gérard. Paratexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Print. Jung, S and Ro. "A Possible Source for Horace Walpole's" Otranto"." ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews, 19. 2 (2006): 33--34. Print. MacAndrew, Elizabeth. The Gothic Tradition in Fiction. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979. Print. Walpole, H. and Lewis, W. S. 2008. The Castle of Otranto. Oxford: Oxford University Press.