Review Paper Final Stage_6614452

advertisement

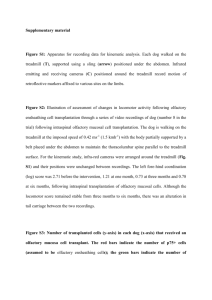

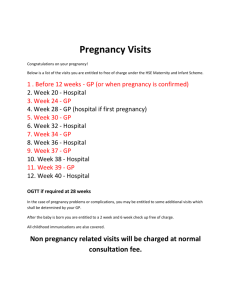

Running head: CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Etiology of Changes in Hedonic Appraisal of Olfactory Stimuli in First Trimester Pregnancy Chalice Walker (6614452) Judith Fortier (7445393) University of Ottawa CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Abstract Changes in olfactory sensitivity during early pregnancy have been theorized to be linked to changes in olfactory processing at a sensory level. Evolutionary theories have proposed that phenomena such as nausea and vomiting during pregnancy are due to heightened objective olfactory sensitivity. Recent research has suggested that this is not the case, but in fact, olfactory perception decreases in sensitivity during early pregnancy. Objective olfactory sensitivity does not increase in pregnant women, though their hedonic odor ratings and strong food aversions indicate a change in subjective olfactory processing at a cognitive level (Köbel N. et al., 2001). Endocrine changes and its effect on neurological structures linked to cognitive olfactory processing linked to hedonic appraisal of odors are discussed. Keywords: hyperemesis gravidarum, hedonic appraisal, human chorionic gonadotrophin. 6614452, 7445393 2 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Etiology of Changes in Hedonic Appraisal of Olfactory Stimuli in First Trimester of Pregnancy An astonishing number of physical and physiological changes occur while women are pregnant. These changes are the most obvious to women in early pregnancy as a result of the critical development that occurs during this period (Profet, 1988). Perceptual changes that occur in pregnancy are widely accepted to have adaptive roles in limiting the number of teratogens that the fetus is exposed to, which may limit or affect its development. The olfactory perceptual system is one of the systems that are altered due to physiological changes that occur during pregnancy. Olfactory sensitivity and processing has been thoroughly studied in pregnant women and changes that onset in pregnancy have been observed. Research on olfactory perceptual changes is relevant because of the connection that it has with hyperemesis gravidarum, also known as nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. The aim of this review paper is to evaluate the literature concerning the olfactory perceptual changes that occur during early pregnancy and the etiology of these changes. Literature Review Hyperemesis gravidarum symptoms are observed in 50% to 80% of women across cultures during the first trimester of pregnancy (Swallow, 2005). To investigate this phenomenon further, researchers have focused mainly on the changes in chemosensory perceptual sensitivity namely taste and smell. Much of the research done before and during the 1990’s suggested that nausea and vomiting during pregnancy were mechanisms of defense against teratogens, which are defined as toxins and dangerous substances that could be harmful for the fetus during the critical period of development in 6614452, 7445393 3 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY the first trimester (Profet, 1988). Consequently, it was proposed that pregnant women experience a modification of their olfactory sensitivity in order to detect a lower threshold of chemical toxins in their environment. An example of this kind of research found that olfactory aversion is stronger towards specific odours such as rum, coffee and cigarette smoke (Nordin, 2004). Pregnant woman perceive these smells as particularly stronger than normal. It is broadly accepted that the chemicals in cigarette smoke and alcohol may endanger the fetus, thus it was believed the heightened olfactory aversion to these odours is an adaptive process that encourages women to avoid these substances during pregnancy (Kölble, 2001). Objective versus Subjective Olfactory Perceptual Changes It should be noted again that pregnant women considered themselves as more sensitive to odours during early pregnancy (Hummel, 2002). Current research conflicts with this report, as results show that objective olfactory sensitivity appears unchanged and may even decrease in pregnant compared to non-pregnant women (Hummel, 2002; Kölble, 2001; Swallow, 2005). This phenomenon can be observed in Figure 1. Swallow (2005) demonstrates only a slight decrease in perception of the pleasantness of both safe and unsafe odours. This raises the question of how women can “feel” as though they have become more sensitive to olfactory stimuli, when their objective olfactory sensitivity remains unchanged, These results bring into question theories concerning the adaptive nature of perceptual changes that occur in early pregnancy. 6614452, 7445393 4 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Figure 1. Ratings of pleasantness of odors for safe and potentially harmful compounds. [- - - - -] non-pregnant women; [— - —] men; ——pregnant women. Increasing pleasantness = low scores, decreasing pleasantness = high scores. (Swallow, 2005, p. 60). The key to the conflict mentioned above, lies in whether objective or subjective perception is assessed. Odour discrimination and odour identification are objective, quantitative methodologies used to assess objective olfactory sensitivity. Hedonic questionnaires using Likert scales assess subjective olfactory experiences and qualitative olfactory sensitivity (Hummel, 2002 & Kölble, 2001). Leslie Cameron’s study (2007) on olfactory hedonics, or pleasantness, found that “pregnant women in their first trimester rated odours as more intense than non-pregnant women” and “pregnant women in their first trimester rated odours as less pleasant than non-pregnant women”. Hedonic questionnaires involve the presentation of an odour after which the subject rates the pleasantness (the highest score on the Likert Scales) or unpleasantness (the lowest score) 6614452, 7445393 5 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY of the odour (Hummel, 2002). The sensitivity of olfactory system can be problematic to test and measure since it is such a highly subjective system; odours are linked to the subject’s internal thoughts and feelings about the odour. The subjectivity of such methods are criticized as being unreliable given that individuals often have varying appraisals of the hedonics of certain odours (Powell, 2013). The above findings, concerning the variances in hedonic appraisal and not in objective sensitivity between pregnant and non-pregnant subjects, led researchers to investigate the causes of olfactory perceptual changes in pregnancy. Data suggests that the major difference between pregnant and non-pregnant women’s olfactory perception is the hedonic ratings of odours, not olfactory sensitivity differences. This research indicates that the changes must occur in mechanisms of perceptual processing rather than the olfactory sensory receptors, and that this change occurs significantly more in the first trimester (Leslie Cameron, 2007). 6614452, 7445393 6 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Figure 2 . Hedonic rating of coffee (mean±SD) in 46 non- pregnant controls and 38 pregnant women. Measurements were taken at sessions 1 (12th week), 2 (21st week), and 3 (36th week) during pregnancy, and 7 weeks after delivery (session 4). Significant differences are only observed between the first trimester of pregnant women and their non-pregnant counterparts (Ochsenbein-Kölble et al., 2007, p.12). Hedonic assessments are highly subjective and subjective appraisal is linked to cognitive processing. This indicates that olfactory perceptual changes in pregnant women may be the result of changes in the cognitive information processing systems (Hummel, 2002 & Nordin, 2005). Studies by Kölble (2001) and Leslie Cameron (2007) suggest that changes in cognitive olfactory processing in pregnancy result from strengthened connections between the olfactory system and the limbic system, the neurological structure responsible for processing emotional information. 6614452, 7445393 7 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Discussion As explained above, there is no objective increase in the ability to detect olfactory stimulus in pregnant women in their first trimester. In fact, their ability to detect and identify olfactory stimulation may decrease in early pregnancy. They do however selfreport from their experience an increased ability to detect olfactory stimuli than before they became pregnant (Ochsenbein-Kölble et al., 2007). This may be for a number of reasons. Most likely, they have stronger reactions to detected olfactory stimuli than their non-pregnant counterparts, particularly stronger aversive reactions to adverse stimuli (Zald and Pardo, 1997). This increase in the emotional component to olfaction may lead women to believe that their objective olfactory perceptual abilities increased in sensitivity. If the olfactory change in women is not at the sensory level of olfactory perception (for example, an increase of olfactory receptor density), what neurological changes in pregnant subjects lead to their altered perceptual experience? This is a difficult question to answer, due to the number of endocrine changes that correlate with the beginning of pregnancy. It is most likely that endocrine changes, due to pregnancy, affect the olfactory processing network in a way that alters the perceptual experience of the individual. A case will be built for a possible mechanism behind these changes in the remainder of this paper. Nature of Olfactory Neurological Pathways and Structures Olfactory processing involves a complex network of neurological structures. In order to understand the effect that the changes in hormone balances have on olfactory processing, it is critical to identify structures that are involved. The sensory pathway of 6614452, 7445393 8 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY the olfactory system runs through the olfactory bulb, which projects the olfactory tract to a variety of structures. These structures include the anterior olfactory nucleus, the olfactory tubercle, the piriform cortex, the entorhinal cortex and the amygdala. The entorhinal cortex sends projections to the hippocampus, which relays information further on to the orbitofrontal cortex (Chaudhuri, 2011). For the purposes of this review, we will focus solely on changes in a number of these structures that belong to the limbic system, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, due to these structures’ particular roles in hedonic appraisal. The amygdala is highly connected to the processing of the hedonic valence of olfactory stimuli. Zald and Pardo (1997) conducted a study using PET neuroimaging to observe amygdala activity under conditions of varying olfactory adhesiveness. This study showed that as hedonic valence ratings decreased (i.e. as olfactory stimuli became more aversive in nature), amygdala activity increased significantly. This demonstrates significant relationship between hedonic assessment of olfactory stimuli and the limbic system. This also supports the claim that if hormonal changes due to pregnancy influence changes in amygdala activity, the hedonic appraisal of olfactory stimuli must necessarily also change. Correlations in Endocrine and Olfactory Hedonic Appraisal Changes Pregnancy is associated with a vast number of hormonal changes, which undoubtedly are related to changes in perceptual processing. The first major change in pregnancy is a great increase in Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG), which peaks at around eight weeks gestation and decreases slowly over the course of pregnancy. This increase is highly correlated with the first trimester, indicating that it likely that changes 6614452, 7445393 9 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY that occur only in the first trimester are at least partially due to the increase in HCG levels. There is slow gradual increases in estrogen and progesterone levels throughout the course of pregnancy, progesterone decreasing slightly near the time of parturition. Figure 3. Relative levels of Human Chorionic Gonadotropin, Estrogen and Progesterone throughout the course of pregnancy (Marghescu, 2014). Galea et al. (2008) have conducted extensive research on endocrine influence on cognitive processing. They demonstrate the effects of estradiol, one of the three circulating forms of estrogen, on the limbic system, specifically the hippocampus. It was observed that estrogen has a great effect on neurogenesis and proliferation in the hippocampus, increasing neural density and activation in this structure. Increases in estrogen, like those associated with the progression of pregnancy, are also known to facilitate an increase in amygdala activity (Innes, 1970). This result is interesting because since estrogen increases consistently through the course of pregnancy, necessitating that 6614452, 7445393 10 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY amygdala activity also increases through the course of pregnancy. Thus, it cannot be estrogen or the amygdala activity that are solely responsible for the changes in hedonic appraisal in first term pregnancy, because their levels and activity increase past the first trimester. More likely it is endocrine changes that are isolated to the first trimester that cause the subjective changes in olfactory sensitivity that occur in the first trimester. Avenues for Future Research Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG) is a hormone that increases and decreases dramatically in the first trimester, with its peak being at 12 weeks (Furneaux, 2001); the same week that hedonic sensitivity is at its peak (Ochsenbein-Kölble et al., 2007). Furneaux et al. (2001) demonstrate that higher HCG levels are positively correlated with hyperemesis gravidarum (2001). The etiology of this process, and the relationship between HCG and hedonic appraisal is still unknown (Furneaux et al., 2001). Due to the known relationship between hedonic sensitivity and the limbic system, a valuable avenue for future research is the relationship between HCG and the limbic system. This relationship could be studied by a neuroimaging study that assessed limbic system activity in pregnant individuals with varying serum HCG levels. Also limbic system activity at experimentally induced increases in HCG could provide valuable information to neuroscientists concerning the causational effects of endocrine changes in limbic activity. This study could also be paired with hedonic assessment of various foods under differing serum levels of HCG. These are excellent avenues for future investigation. Conclusion In conclusion, research shows that it is not an increase in objective olfactory perception that occurs in pregnant women in their first trimester, but a change in 6614452, 7445393 11 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY subjective olfactory response mechanisms and hedonic appraisal. Changes in the neural networks that process olfactory information, like the limbic system, occur due to major endocrine changes that occur in pregnancy, and it is these neural changes that lead to the changes in hedonic appraisal. The changes in hedonic appraisal are the most dramatic during first term pregnancy, leading us to investigate endocrine changes that are isolated to first term pregnancy. Human Chorionic Gonadotropin levels are significantly increased during first trimester pregnancy, making it a likely contributor to changes in limbic activity and hedonic appraisal during pregnancy. The etiology of the changes in hedonic assessments is still unknown, though it is likely related to an increase in HCG levels. 6614452, 7445393 12 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY References Chadhuri, A. (2011). Fundamentals of Sensory Perception. Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. Furneaux, E., Langley-Evans, A., & Langley-Evans, S. (2001). Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy: Endocrine Basis and Contribution to Pregnancy Outcome. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey, 56(12), 775-782. Galea, L. A. M., Uban, K. A., Epp, J. R., Brummelte, S., Barha, C. K., Wilson, W. L., . . . Pawluski, J. L. (2008). Endocrine regulation of cognition and neuroplasticity: Our pursuit to unveil the complex interaction between hormones, the brain, and behavior. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale, 62(4), 247-260. doi:10.1037/a0014501 Hummel, T., Mering, R. V., Huch, R., & Kölble, N. (2002). Olfactory modulation of nausea during early pregnancy. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 109, 1394-1397. Innes I. D. L., Michael E. K. (1970). Effects of Progesterone and Estrogen on the Electrical Activity of the Limbic System. Journal of Experimental Zoology 175, 487-492. Kölble, N., Hummel, T., Mering, R. V., Huch, A., & Huch, R. (2001). Gustatory and olfactory function in the first trimester of pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 99, 179-183. Leslie Cameron, E. (2007). Measures of human olfactory perception during pregnancy. Chemical Senses, 32, 775-782. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjm045 6614452, 7445393 13 CHANGES IN OLFACTORY HEDONIC APPRAISAL IN PREGNANCY Marghescu, D., Molecular Endocrinology Laboratory: Reproductive Hormones (2014). McGill Physiology Virtual Lab. Retrieved from http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/physio/vlab/other_exps/endo/reprod_horm.htm on October 24th, 2014. Nordin, S., Broman, D. A., & Wulff, M. (2005). Environmental odor intolerance in pregnant women. Psychology and Behavior, 84, 175-179 Ochsenbein-Kölble, N., von Mering, R., Zimmermann, R., Humel, T. Changes in Olfactory Function in Pregnancy and Postpartum. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2007, 97(1), 10-14 Powell, R. A., Honey, P. L., Symbaluk, D. G. (2013). Introduction to Learning and Behavior, 4th edition. Wadsworth: Jon-David Hague. Profet, M. (1988). The evolution of pregnancy sickness as protection to the embryo against Pleistocene teratogens. Evolutionary theory, 8, 177-190. Swallow, B. L. et al. (2005). Smell perception during early pregnancy: no evidence of an adaptive mechanism. BJOG: an International Journsl of Obstetrics & Gynaecology,112, 57-62. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00327.x Zald, D. H., Pardo, J. V. (1997). Emotion, olfaction, and the human amygdala: Amygdala activation during aversive olfactory stimulation. Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94(8), 4119–4124. 6614452, 7445393 14