Bell Manuscript - University of Manitoba

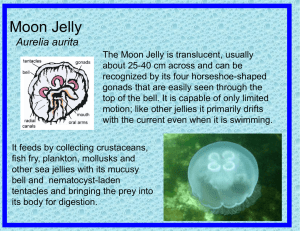

advertisement