Speech Given by Robert Griffiths QC at the Shale Gas Conference

advertisement

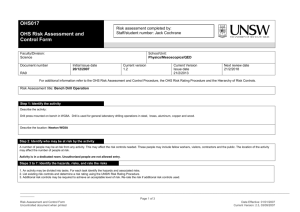

Speech Given by Robert Griffiths QC at the Shale Gas Conference for the Westminster Energy and Transport Forum (23 June 2015) 1. Lawyers, especially Queen’s Counsel as a breed, do not normally show a propensity for answering difficult questions simply or for that matter, simple questions simply. The principle of Occam’s Razor is lost on them, if not on judges. But let me have a go in the five minutes I have got. 2. The question is, why has the shale gas revolution in the US not yet taken off in the UK? J Paul Getty said, “the meek shall inherit the earth but not its mineral rights.” Gregory Zuckerman, in his book The Frackers has suggested that it is the innate lack of entrepreneurial spirit in the UK and Europe which explains the difference. He says we do not have the wildcatters and entrepreneurs who took a chance on drilling shale and other rock formations. To use an Americanism, I do not buy that. It is true there was nothing meek about the shale gas revolution in America, but there is also nothing meek about the British oil and gas industry. It has the necessary entrepreneurial spirit – the problem is that it has not been given its head. 3. The real answer to the question is that there are serious legal impediments in the way of speedy and effective exploitation. They relate to the ownership of mineral rights, access to land and the absence of a bespoke or streamlined planning and regulatory regime. Ownership 4. In the US, landowners own the sub-surface mineral rights. There is, therefore, an incentive for a landowner not to prevent the exploitation of the mineral resource beneath their property. In the UK, since the Petroleum Act 1934, the Crown owns these subterranean rights. It is for that reason that operators have to obtain Government licences to search for and produce gas and oil. Access to land 1 5. In a Supreme Court case in 2010 (Star Energy v Bocardo [2010] UKSC 35) it was held that an operator commits a trespass to land if he drills underneath the land without the surface owner’s consent to drill. If the landowner refuses to grant the consent, the operator’s only remedy is to acquire those rights using a rarely used procedure under the Mines Working Facilities and Support Act 1966. This is a pretty hopeless remedy as the landowner will get nominal compensation but has the ability to obstruct the process. 6. Related to that obstacle is that when the Petroleum Act of 1934 was enacted, exploration and production was limited to vertical drilling. Subsequent legislation, until the Infrastructure Act 2015, did not reflect the advance in technology which enabled directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing to extend over significant areas of multiple land ownership. 7. It is only in the last few months since the Infrastructure Act that the problem of getting access to land has been addressed (at least to some extent). Sections 43-48 of that Act deal with the right to use what is called “deep-level land” in any way for the purposes of exploiting petroleum or deep geothermal energy. Deep-level land is any land with a depth of at least 300 metres below the surface level. This means that horizontal drilling can take place lawfully without the consent of the owner. But it is not clear from the statute as to whether that applies to vertical drilling. No bespoke planning or regulatory system 8. There is no bespoke or streamlined regulatory and planning framework for onshore exploration and production. There is no doubt that the regulatory regime is thorough and addresses the planning, environmental and health issues. But the system lacks coordination and is unnecessarily complicated with the responsibilities shared between various departments and government agencies. Before coming today I counted up the number of consents, permissions, consultations and notice provisions that have to be complied with in order lawfully to drill an onshore oil well in the UK. There are at least 13. Suffice it to say at this stage, I agree with what was reported by the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee in May 2014 that, “bureaucratic complexity and the diffusion of authority are not the best basis for clear and effective regulation of a new and fast evolving industry.” It is axiomatic that complexity does not increase the quality of regulation. 2 9. A topical illustration of this is what is happening today in the Council Chamber of County Hall, Preston. I must say, this is either a remarkable coincidence or the organisers of this event are blessed with the gifts of prophecy because as many of you may know, Lancashire County Council’s Development Control Committee is today considering two applications made by Cuadrilla for planning permission to drill, hydraulically fracture and test the flow of gas from a small number of horizontal exploration wells at Preston New Road, Little Plumpton and Rose Acre Wood in Preston. 10. I have brought with me the documentation which the lay Planning Committee will have to consider, digest and evaluate. It runs to over 800 pages and includes a welter of expert reports and documentation relating to planning, energy, ecological, environmental, transport, air quality, economic, geological, geophysical, hydrological, archaeological, legal and arguably metaphysical issues. In my estimation it would take a specialist planning and environmental lawyer a week to read, let alone fully analyse the material before them. I do not seek to deprecate the maintenance of the democratic processes operating through our planning and regulatory system, but I am bound to say in conclusion there must be a more focused, effective and informed way of making decisions of national significance which will affect this country’s future energy supply, security and economic wellbeing. Robert Griffiths QC 4-5 Gray’s Inn Square 23 June 2015 3 Appendix A Consents, permissions, consultations, notices and documents which may need to be submitted in order lawfully to drill an onshore oil well in the UK 1. Licence to drill from the Department of Energy and Climate Change 2. Permission from the Coal Authority if the well encroaches on coal seams 3. Planning Permission from the Local Minerals Planning Authority 4. The Health and Safety Executive 5. The Environment Agency 6. The Highways Agency 7. An Environmental Impact Assessment 8. An Environmental Permit 9. An Environmental Risk Assessment 10. Compliance with the Human Rights Act 1998 and European Directives 11. British Geological Society 12. Public Heath England 13. When section 50 of the Infrastructure Act 2015 is in force, a hydraulic fracturing consent 4