Historical Institutionalism Summary

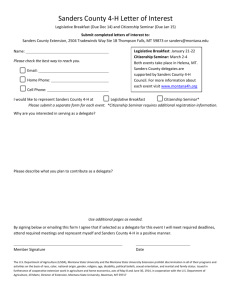

advertisement

Historical Institutionalism Elizabeth Sanders Elizabeth Sanders begins her interpretation of historical institutionalism by defining it as the study of human political interaction in context of rule structures, viewed sequentially, and relying on path dependence. Essentially, it is as the name implies, the study of institutions across history. Historical institutionalism has enjoyed a strong reputation over the past century, yet has gone in and out of popularity. Following the invention of the computer in the 60s, the popularity of HI waned as the computer made it easy to analyze large sets of data. Yet, it returned to prominence in the 70’s as western liberalism was challenged and scholars needed a way to examine the health of western liberal institutions. At the same time, the epistemology of HI and rational choice came to the fore front. As the “Chicago School” argued for rational choice, there was a parallel rebellion against pluralism. Although both schools saw institutions as constraints, they differed in how they studied and interpreted those constraints. Rational choice theorists looked toward the individual across a slim time frame, whereas, HI theorists saw constraints within the construction, maintenance, and adaptation. They focused on goal oriented actors and the outcomes they achieved which lead them to the study of ideas. Ideas in the HI theorist world were the glue and motivation that held institutions together and force them to adapt respectively. The focus on ideas pushed them towards philosophy and history, and lead them to conclude about the long term viability and broad consequences of institutions. Conversely, believers of rational choice sought to determine the motivations of the individual actors, and thus studied their motivations and were lead to a heavier emphasis on mathematics. RC was founded on abstraction, simplification and analytical rigor; related to math and economics. RC pays more attention to the parameters of particular moments in history that are the setting for the individual self-interesting maximization. HI was founded on dense, empirical description and inductive reasoning; related to history and philosophy. HI pays more attention to the long-term viability of institutions and their broad consequences. These ides could be antithetical, or could be complementary. Three Varieties of Historical Institutionalism: Agents of Development and Change Institutions are human-designed constraints on subsequent actions, but who designs? Exogenous social forces or internal group dynamics -> agency-in-change receives a lot of HI attention. HI studies path establishment and institutional change, focusing on prime movers in the genesis and development of institutions. Some analysts start at the top with Presidents, judges, and high-level bureaucrats. Some start from the bottom with the broader public, particularly social movements and groups motivated by ideas, values and grievances. Some believe in an interactive approach, others are comparatives that prefer a multifocal search for actors and conditions that produce different national outcomes. Choice of focus changes methodology. Top – documents, decisions, speeches, memoirs, and press reports. Bottom – social movements, voters, legislators, and quantitative analysis. HI is definitely a messy genre. Institutional Formation and Change from the Top Down For the explanation of the birth and development of the modern state focus on the top – like neo-Marxist and other elite focused historians. HI develops as a sub-field of APD with the creation of a new section of politics and history in the American Political Science Association. The historical analysis assumed the same – that institutional development unfolds on sites with rule structures and holders of ‘plenary authority.’ It gives little attention to ‘ordinary people.’ Social movements were viewed as inconvenient obstacles; farmers, reps in Congress, jealous judges were main obstacle to the holistic modernization schemes of visionaries in the Interstate Commerce Commission and Senate. Skowronek focuses on the beginning of national railroad regulation, the fight for meritocratic civil service and the struggle for a permanent professional army. Elites were viewed as the prime movers in each case: intellectuals/businessman, Midwestern senators, Presidents/generals. Think monetary policy with financial elites, central banks and stable currencies. Think military decisions with the expansion of the bureaucracy under the President and the rationalization of the military through Congress. HI shifts to political parties, elites, public philosophies and policy foci. Sanders discusses how sociologists, historians and political scientists were uncomfortable with the idea that the elites were "the motor of history". She discusses the affects that social groups have on the politics and policy. Sanders claims that social mobilization often called for new or expanded governmental institutions. She claimed also that once a policy and institution were in place that group demands and coalitions would then shape themselves based on the "interpretation of rules by public officials." Sanders discusses that perhaps the most interesting subject to study is labor and its development over time. Once labor unions began to form they're existence shaped laws and the personnel who cared out the laws to their advantage. Southern influence used it to protect what was deemed their interests. Sanders also touched on that size of the presidency and "war making powers" and the ballooning of the institution. Sanders suggested that further study of the institution as a whole should be conducted rather than just that of the people within each office.